by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 29/01/2018

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Arcimboldo' in Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica di Palazzo Barberini, until February 11, 2018.

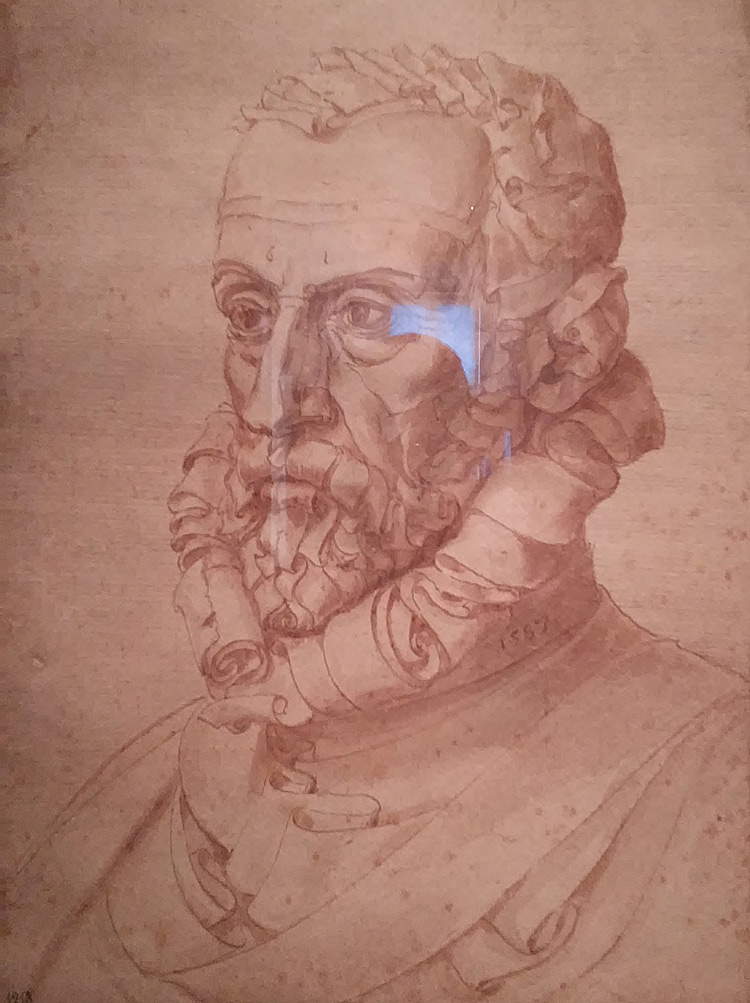

One of the last works we know of Giuseppe Arcimboldi, the great sixteenth-century artist also known, more simply, as Arcimboldo (Milan, 1527 - 1593), is one of his highly original self-portraits on paper, preserved today at the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe (Drawings and Prints Cabinet) of Palazzo Rosso in Genoa. Keeping true to the genre that had brought him fame in his lifetime and would grant him imperishable glory later, Arcimboldo avoided opting for a traditional self-portrait, and also painted himself in the form of a compound head, that is, accumulating a series of objects to shape his figure. From a distance it would appear to be a normal self-portrait, but if you get closer you will notice that the painter’s head is composed entirely of sheets of paper, and looking more closely at the wrinkles on his forehead the observer will notice how the artist concealed a 6 and a 1 between the folds of his skin: sixty-one was in fact the age the artist was when he painted the work. He made it upon his return to his hometown after spending two decades at the court of the Holy Roman Empire. “It is evident,” wrote Giacomo Berra in 1996 in an essay entirely devoted to theSelf-Portrait, "that Arcimboldi, as soon as he arrived definitively in Milan, in proposing his own Self-Portrait to his fellow citizens almost exalted its value as a synthesis of his pictorial formula by also visually illustrating through drawing his peculiar stylistic figure." But not only that: that very special Self-Portrait was configured as a kind of declaration of intent.

And it is also for this reason that the work opens the path of the Arcimboldo exhibition, currently running in Rome at Palazzo Barberini until Feb. 11. After he returned to Milan, Giuseppe Arcimboldi surrounded himself with intellectuals and men of letters such as Paolo Morigia, Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo (who was also a talented painter) and Gregorio Comanini, and he began to entrust them with the account of his memoirs, particularly of what he had done at the imperial court, not without failing to self-celebrate. “Un pittore rarissimo, unico nell’inventioni, leggiardo e miracoloso ne’ ghiribizzi, e bizzarrie,” Comanini called him, and of the same opinion was Morigia, who wrote “questo è un pittore raro, et in molte altre virtù studioso, et eccellente; et dopo l’haver dato dato saggio di lui, e del suo valore, così nella pittura come in diverse bizzarrie, non solo nella patria, ma anco fori, acquistssi gran lode, di maniera, che il grido della sua fama volò fino nell’Alemagna”. The meaning of the work thus appears clearer: those blank, empty sheets, with which Arcimboldo constructs his self-portrait, will be to be filled with words that can celebrate his art, extolling the successes that the Milanese painter was able to achieve. The narrative of the Roman exhibition begins right here: we must imagine, therefore, the artist taken to retrace his life and career, recounting his memories, remembering the people he met, the celebrations he had taken part in, the splendid works he painted for his refined patrons. And all under the banner of those “oddities” that characterized his production.

|

| Entrance to the exhibition on Giuseppe Arcimboldi in Rome. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| A room of the exhibition. Ph. Credit National Galleries of Ancient Art. |

|

| A room from the exhibition. Ph. Credit National Galleries of Ancient Art |

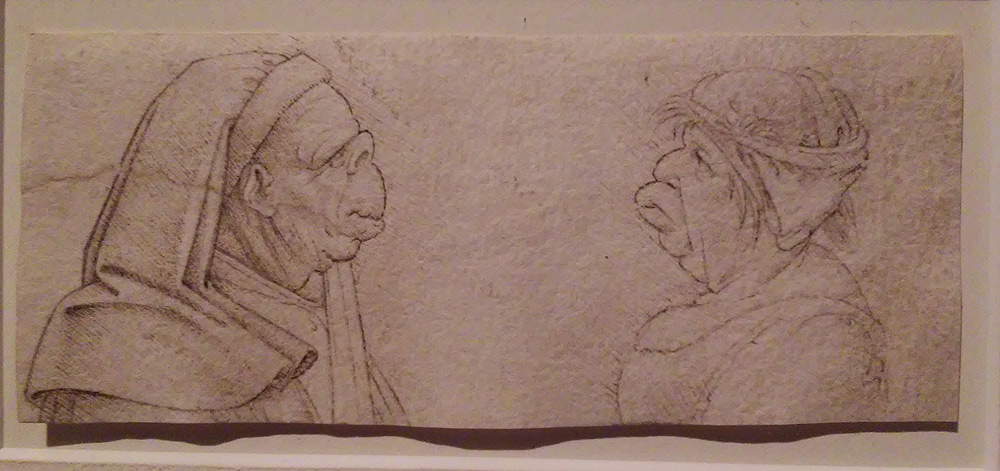

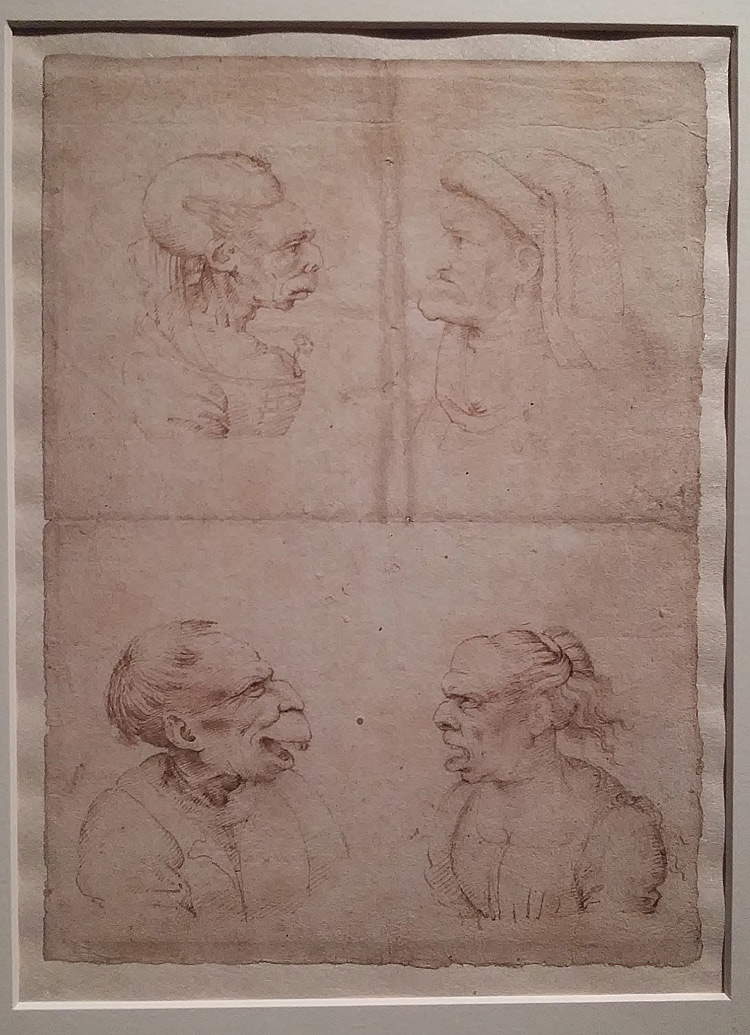

“Bizarre” is a word that recurs frequently in the writings of those who have dealt with Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s painting: his is an almost unique case in the history of Western art, since few artists had such an imaginative flair as his, and no one had ever thought of creating oddities such as portraits composed of objects, plants, animals. In the collective imagination, therefore, the image has spread of an ingenuity substantially out of time and out of all context, probably developed thanks to some equally strange conjuncture. Those “oddities,” on the other hand, are well rooted in the cultural substratum of Milan in the mid-sixteenth century, and the exhibition starts well by reconstructing the genesis of the Arcimboldesque “whims”. It should be emphasized that we know very little about the artist’s Milanese years, partly because, upon his return to the city in 1587, Giuseppe Arcimboldi preferred to gloss over the first part of his career, and focused on the years he spent at the Habsburg court. What is certain is that Arcimboldo must have been immersed in art from an early age, since his father Biagio was also a painter and had been active for years at the Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo. Lombard art had been distinguished, from earlier times, by a taste for lively narrative and great attention to reality and nature: a predisposition, moreover, nurtured by the arrival in Milan of Leonardo da Vinci and the spread of his theories on theobservation of nature as the basis for scientific progress and as the foundation of knowledge, and on drawing as the privileged means of conducting such study. Studying nature meant investigating even its most unusual and paradoxical aspects-a lesson that Leonardo da Vinci imparted to his pupils and the artists in his circle, whose task it was to preserve and disseminate it. It is precisely in Leonardo da Vinci and the Leonardesque artists that we need to find the most direct precedents for Arcimboldo’s heads: the great Tuscan artist, in order to consolidate his studies in the field of physiognomy and thus to improve his knowledge of the human face, and probably prompted, as suggested in the catalog, by the burlesque literary facetiae widespread at the court of Ludovico il Moro, had taken to drawing grotesque heads, caricature portraits with exaggerated features and deformed to the point of the improbable. His pupils were not to be outdone: two drawings arriving from Montréal, one attributed to Francesco Melzi (Milan, c. 1491 Vaprio d’Adda, c. 1570), and the other to an anonymous follower, are examples of this in the exhibition.

Probably inspired by these unusual figurations, and wishing to invent a genre that combined a taste for the bizarre with a careful study of the natural, an area in which Giuseppe Arcimboldi excelled (evidence of which are also the various drawings on naturalistic subjects that remain of him), the artist, shortly before moving to Vienna, began to produce his composite heads, the earliest examples of which are perhaps to be found in the Seasons now in Munich. This is a complete cycle (althoughAutumn is in a very precarious condition: it is therefore preserved in the deposits of the Alte Pinakothek in the German city), which is particularly problematic: at one time the works that compose it were believed to have been executed during his stay at the Habsburg court, if not actually copies of inventions conceived in Austria. With the exhibition on Arcimboldo held at the Royal Palace in 2011, scholar Francesco Porzio had first proposed the suggestive hypothesis of assigning the Munich Seasons to the Milanese years, which has now also been accepted by the curator of the Roman exhibition, Sylvia Ferino-Pagden: the inferior quality compared to that of other composed heads by Giuseppe Arcimboldi but still totally compatible with the artist’s achievements, as well as the debts to Lombard naturalism, are the main clues that have led to a dating to about 1555-1560. A dating that would fill an important gap within Arcimboldo’s career and help explain the reason for his move to Vienna.

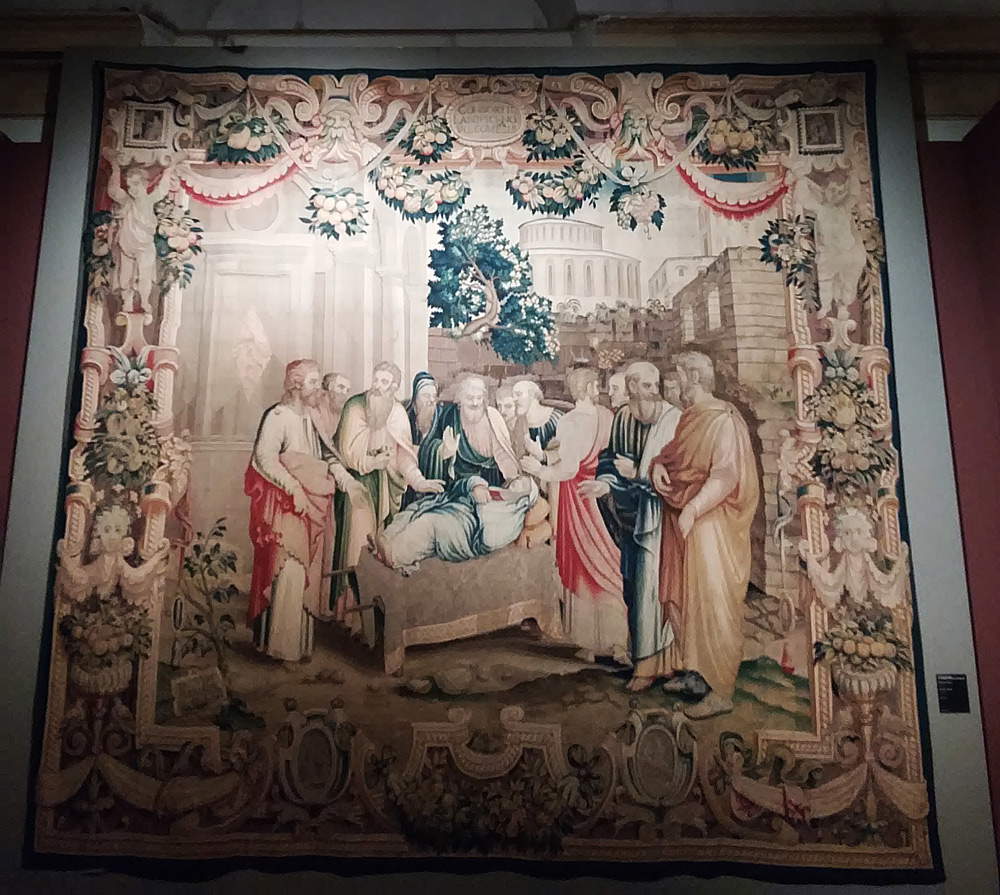

Of Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s early Milanese period, after all, we know very little, and much of what is known to us is contained within the rooms of the exhibition. The artist began working together with his father relatively late, at the age of twenty-two, assisting him in the creation of cartoons for the stained glass windows in the cathedral and following the same task for several years: in the exhibition we have two stained glass windows, those with St. Catherine Being Taken to Prison and theExecution of St. Catherine, made to Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s own design. These are conventional works, admittedly refined and up-to-date, as is the large tapestry of the Dormitio Virginis, also in the exhibition, for which Arcimboldo drew the cartoon (the scene is treated in a traditional manner, although the painter’s taste can be discerned in the large festoons of fruit and flowers that frame the composition), or like the frescoes with theTree of Life in Monza Cathedral: those just listed are among the very rare works that we know of the painter up to the date of his move to Vienna, and we can certainly consider them insufficient to have moved the curiosity of Emperor Maximilian II of Habsburg (Vienna, 1527 Regensburg, 1576), who called the artist to Austria in 1562, a time when the ruler was working to gather around him one of the most fruitful cultural and humanistic circles in Europe at the time. Arcimboldo evidently worked a great deal for private clients, executing works of which no trace remains, or, since the Habsburgs also entrusted him with the organization of court festivities, it is conceivable that already in Milan the painter was able to distinguish himself as a skilled stage designer, capable of attracting the attention of his future illustrious patrons. It is certain that already in Milan the artist had to emerge for his extravagant works, as Morigia would imply in the passage from the Histories of Milan quoted just above, in which he says that because of the bizarre things that Arcimboldo was able to achieve, “the cry of his fame flew as far as nellAlemagna”: perhaps, just the heads of Munich are to be included in the list of Milanese “bizarre things” capable of making “the cry of his fame” fly.

|

| The beginning of the exhibition. Ph. Credit National Galleries of Ancient Art |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, Paper Self-Portrait (1587; traces of pencil, pen and ink, brush and watercolor ink, gray watercolor on white counterfold paper; 442 �? 318 mm, Genoa, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe di Palazzo Rosso) |

|

| Francesco Melzi (attributed to), Two Heads Charged (by Leonardo da Vinci) (Pen and brown ink, 43 �? 103 mm; Montréal, Rolando Del Maestro) |

|

| Follower of Leonardo da Vinci, Caricatures (Pen and brown ink, 202 �? 150 mm; Montréal, Rolando Del Maestro) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi,Summer andWinter in Munich |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, LEstate (c. 1555-1560; oil on canvas, 68.1 �? 56.5 cm; Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, LInverno (c. 1555-1560; oil on panel, 67.8 �? 56.2 cm; Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, Santa Caterina viene condotto in prigione (before 1556; stained glass panel; Milan, cathedral, stained glass window of santa Caterina dAlessandria) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, Execution of St. Catherine (ante 1556; stained glass panel; Milan, cathedral, stained glass window of St. Catherine of Alexandria) |

|

| Giovanni Karcher on cartoon by Giuseppe Arcimboldi, Dormitio Virginis (1561-1562; wool and silk, 423 �? 470 cm; Como, Cathedral) |

The next room is probably the most evocative of the exhibition, since the curators imagined it to give the visitor the feeling of being inside one of the halls of the imperial palace in Vienna, with Arcimboldo’s paintings on the walls as they were imagined. Thus we find side by side the four paintings of the Seasons and the four paintings of the Elements, all composite heads obtained, in the first case, by juxtaposing vegetables, flowers and fruits of the respective seasons of the year, and in the second case objects or animals designed to recall the idea of each of the four elements. Certainly: in order to permit such a reconstruction it was necessary to resort to individual paintings from different cycles, with the result that the supports are different (we find, within the two series, canvases and panels mixed together), that the dimensions sometimes differ, and not just a little, and that there are some chronological digressions (for the Primavera the Munich panel was chosen, which, as mentioned, should be ascribed to the early Milanese period). But it is equally true that, in an exhibition endowed with great popular value, we can consider a small concession on the philological level fully acceptable if the aim is to reconstruct a context (one of the strengths of the exhibition is, after all, the great ability to be able to create an appropriate historical and cultural context for each room). The paintings includeWinter of 1563, a work belonging to the Seasons cycle that the artist executed soon after his arrival in Vienna. The public cannot help but appreciate Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s extraordinary inventiveness:Winter is an old man made from a bare tree trunk, with dry branches and ivy leaves forming his hair, a mushroom for his lips, and a mat as his robe. Similarly, Spring is composed of the most beautiful and colorful varieties of flowers (roses, daisies, carnations, anemones, forget-me-nots, and several others-about eighty varieties have been identified),Summer of the fruits and vegetables typical of the season (peaches, plums, cherries, cucumbers, and a robe formed of ears of corn), whileFall is a large barrel filled with mushrooms, grapes, and pumpkins. These paintings, writes Sylvia Ferino-Pagden, “are an extraordinary combination of mimesis and fantasy: the two fundamental concepts for artistic invention popularized by sixteenth-century art theorists.”

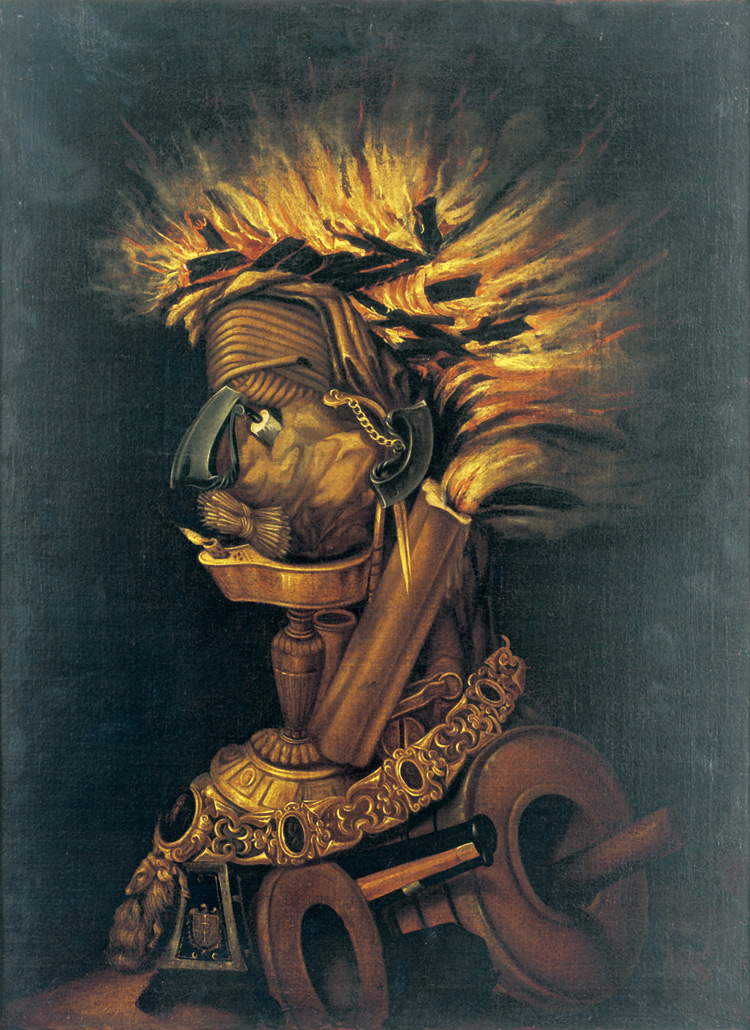

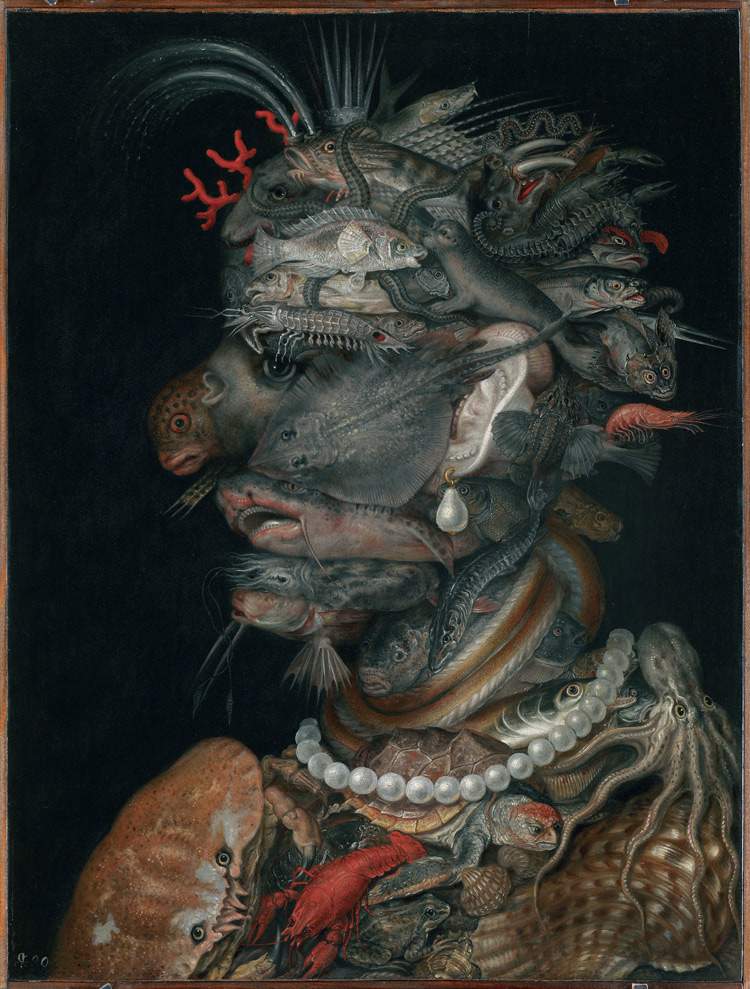

The literati of the imperial court probably suggested to Maximilian II that he integrate the cycle of the Seasons with that of the Elements, based on the ancient theories that associated each season of the year with one of the four elements. Giuseppe Arcimboldi executed them so that they were each placed in front of their own season, as if the characters were looking at each other: Spring is associated withAir, a very ingenious composition of only birds;Summer is contrasted with Fire, resulting from the union of flashlights, flashlights, lamps and other instruments;Autumn is situated in front of Earth, which likeAir is composed of only animals (horses, lions, elephants, sheep, deer, dogs, rabbits, wild boars and many others); and finallyWinter is paired withWater, consisting of over sixty species of fish and aquatic animals. These are interesting compositions not only for their unquestionable originality, but also for other lesser-known but enriching aspects: first of all, the fact that the Habsburgs considered the composed heads to be serious celebratory works, which, however playful, alluded to their qualities as rulers, based on the principle of serious ludicrousness evidently capable of finding good reception at the imperial court. Thus, Fire wears the collar of the Golden Fleece around its neck, inAir we observe the imperial eagle and the peacock, a bird that is part of some of the dynastic coats of arms of the Habsburgs, and, as the curator again suggests, “the variety of animal and plant species that coexist harmoniously in Arcimboldo’s composite heads symbolizes the peace and prosperity of Maximilian’s reign.” Another key aspect is that the composite heads required careful study of the individual elements that made them up.Giuseppe Arcimboldi has left us a good number of drawings of plants and animals in this regard, and in his study activities he was certainly favored by the climate of the Habsburg court.

|

| The hall of the seasons. Ph. Credit National Galleries of Ancient Art |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, The Spring (c. 1555-1560; oil on panel, 68 �? 56.5 cm; Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, LEstate (1572; oil on canvas, 91.4 �? 70.5 cm; Denver Art Museum Collection, bequest from the Helen Dill Fund, inv. 1961.56) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, THE AUTUMN (1572; oil on canvas, 91.4 �? 70.2 cm; Denver Art Museum Collection, bequest from the John Hardy Jones Collection, inv. 2009.729) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, THE WINTER (1563; oil on linden wood, 66.6 �? 50.5 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie, inv. GG 1590) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi (?), LAria (post 1566; oil on canvas, 74 �? 55.5 cm; Switzerland, private collection) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi (?), The Fire (post 1566; oil on canvas, 74 �? 55.5 cm; Switzerland, private collection) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, The Earth (1566?; oil on panel, 70.2 �? 48.7 cm Vienna, Liechtenstein - The Princely Collections, inv. GE2508) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, LAcqua (1566; oil on alder wood, 66.5 �? 50.5 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie, inv. GG 1586) |

|

| Winter andWater. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

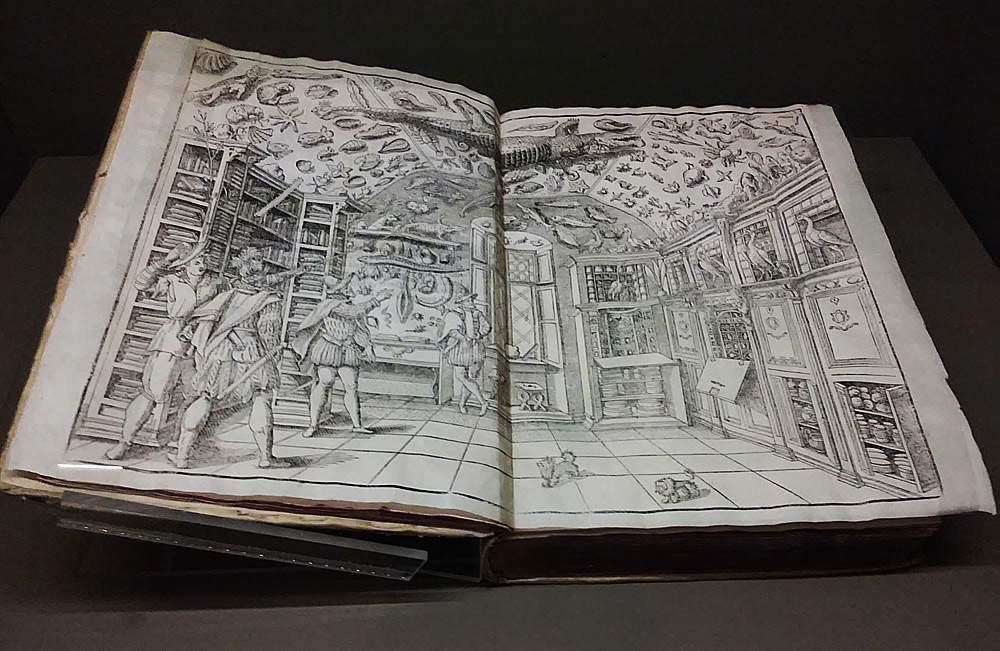

This climate is well evoked in the next section, devoted to nature studies and the Wunderkammer. Maximilian II’s successor, Rudolph II (Vienna, 1552 Prague, 1612), moved the capital of the empire to Prague in 1583 and set up an impressive chamber of wonders there in which he collected objects from every corner of the world: instruments, plants, animals, works of art, relics, automata, and the stranger or more curious these objects were, the greater the interest they aroused in the emperor. The use of the Wunderkammer had the precise purpose of endowing the court with an important instrument of knowledge that could assimilate the most varied things in the world, so much so that such rooms were always flanked by libraries, as we note when observing, in the exhibition, the View of the Museum of Ferrante Imperato in Naples, a print reproducing the exceptional Wunderkammer of the Neapolitan naturalist Ferrante Imperato (Naples, 1550 1631). The imperial libraries held the works of naturalists, from which Arcimboldo was also able to benefit: the Roman exhibition hosts some examples, starting with the Historia animalium by Conrad Gessner, one of the leading scientists of the Habsburg court. One part of the exhibition, moreover, tries to reconstruct a cabinet from a chamber of wonders: there we find eccentric lamps in the shape of a satyr’s head, very strange cups created from coconuts, walrus tusks and shark jaws, and the ever-present sprig of coral. It is not far-fetched to imagine that even some of Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s paintings were intended for a Wunderkammer, not least because, Giuseppe Olmi and Lucia Tomasi Tongiorgi write in the catalog, Arcimboldo’s head paintings were objects as much in keeping with the philosophy of Wunderkammern: not only insofar as they were generically squiggly, and rare in the world, but also because the naturalistic subjects skillfully and realistically rendered, that is, hollowed out of the natural, by the painter, made them, after all, amalgams of art and nature and finally compendia in reduced space of broad and diversified realities (flora, aquatic and terrestrial fauna).

Arcimboldesque acumen then finds one of its peaks in the so-called reversible heads: compositions that, when viewed from one side, appear to be simple still lif es of fruit and flowers, and when turned upside down become striking portraits. These are works evidently imagined to arouse astonishment at court parties, but there is more to them than that: they are in fact paintings that helped define the nascent genre of still life, and this role of theirs is well emphasized in the exhibition. Giuseppe Arcimboldi got to know Giovanni Ambrogio Figino (Milan, 1553 1608), considered the inventor of still life, and Fede Galizia (Milan, 1578 - 1630), also a skilled still life painter, whose works were introduced to the court of Rudolph II by Arcimboldo himself: the links with these two important artists might suggest a decisive role of the Milanese painter in the birth of the new and successful pictorial genre. A genre that the great Caravaggio would also look to a few years later, no doubt intrigued by the works of Arcimboldo and colleagues and fascinated by their distinct sense for naturalism.

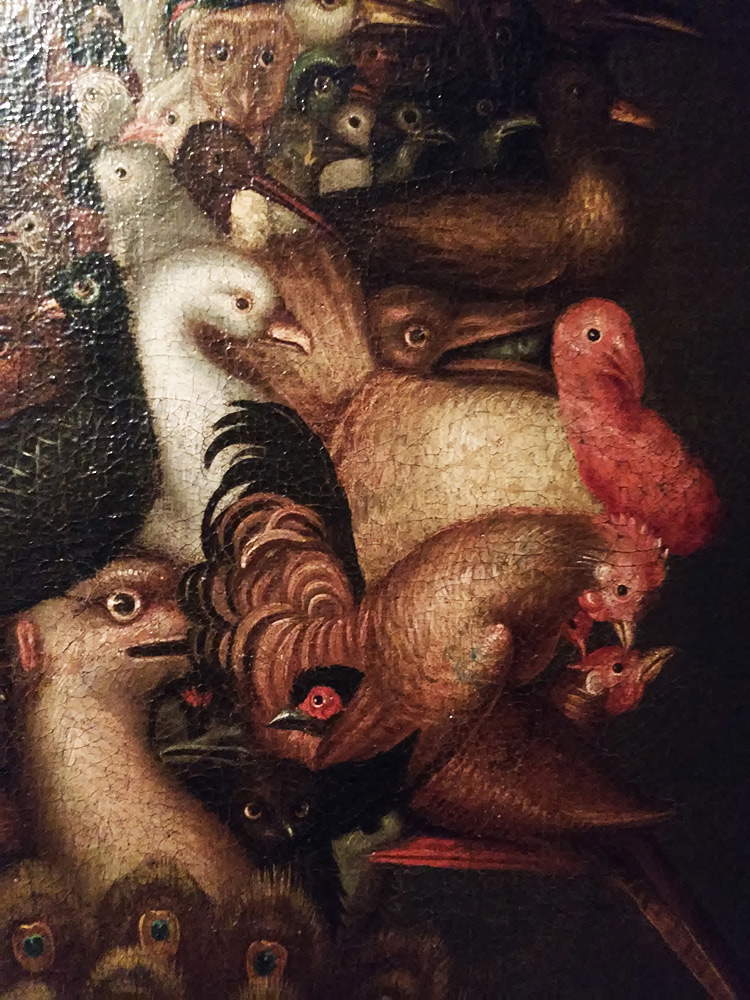

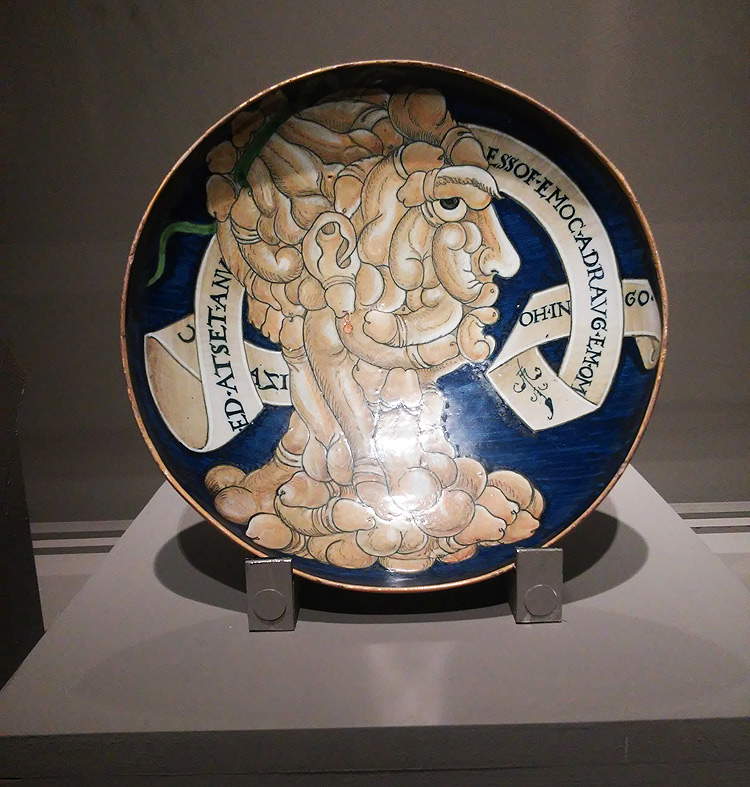

The exhibition continues with the small hall dedicated to the “bel composto,” in which are arranged a number of works by artists who, taking up the Arcimboldesque lesson or anticipating it, worked with imagination to give life to equally original compositions: not to be missed is the anthropomorphic landscape by Wenceslaus Hollar, and above all the ironic and tasty “head of cocks,” a ceramic, attributed to Francesco Urbini (documented in the 1630s), depicting a head composed exclusively of phalluses of various sizes, accompanied by pungent cartouche that reads “ogni homo me guarda come fosse una testa de cazi,” and in advance of Arcimboldo’s works, since it is a work from 1536, probably executed for mere burlesque purposes. The last room, on the other hand, is reserved for the so-called “ridiculous paintings,” direct descendants of the grotesque heads of Leonardo da Vinci and Francesco Melzi: these are still composed heads, but made with caricature intent. Thus, if the Jurist, with his face made up of roasted chickens and fish, probably mocks Johann Ulrich Zasius, the rigid chancellor of Maximilian II, the Librarian might mock the historian Wolfgang Laz, with the many books stacked on top of each other to mean that his production would have been distinguished more by quantity than quality. Satire was also a tool that Arcimboldo mastered with dexterity.

|

| The section on the Wunderkammer. Ph. Credit National Galleries of Ancient Art. |

|

| Objects in the cabinet of the Wunderkammer. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Top: Pitcher with coconut (second quarter 17th century; coconut, partly gilded silver mount, height 31 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Kunstkammer, inv. KK 9047). Bottom: Spherical coconut cup (17th century; coconut, silver mount, 10 �? 8 cm; Koelliker Collection, LKWA0002). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| View of Ferrante Imperato’s Museum in Naples, in Ferrante Imperato, Dellhistoria naturale , Vitale, Naples 1599 (Rome, Biblioteca Universitaria Alessandrina, Y.h.38) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, LOrtolano (Priapus) / Bowl of Vegetables (c. 1590-1593; oil on panel, 35.8 �? 24.2 cm; Cremona, Museo Civico Ala Ponzone) |

|

| Faith Galicia, Still Life (late 16th-early 17th century; oil on panel; Milan, private collection) |

|

| Wenceslaus Hollar, Anthropomorphic Landscape (ante 1662; Etching, 128 �? 199 mm; Oxford, The Ashmolean Museum, bequest of Francis Douce, 1834, inv. WA1863.6452) |

|

| Francesco Urbini (attributed to), Dish with Compound Head of Fouls also known as Head of Cocks (1536; Majolica, diameter 23.2 cm; Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, inv. WA1863.3907) |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, The Jurist (1566; oil on canvas, 64 �? 51 cm; Stockholm, Nationalmuseum) |

|

| Copy from Giuseppe Arcimboldi, The Librarian (oil on canvas, 97 �? 71 cm; Sweden, Skokloster Castle) |

The Arcimboldo exhibition continues the work of critical relocation of the artist that began at least since the double exhibition in Vienna and Paris in 2008 and continued with the Palazzo Reale exhibition in Milan in 2011. An operation that over the years has ensured Giuseppe Arcimboldi’sexceptional popularity, evidenced by the growing number of requests for loans for exhibitions set up in the most unthinkable places (for example, an exhibition on Arcimboldo is now also underway in Spain, in Bilbao). Even for the Palazzo Barberini exhibition, of course, ties to the territory are completely absent, since Rome never appeared on Arcimboldo’s radar: simply, the artist is experiencing the fate that befalls all the greats of the past who become true stars of exhibitions, so much so that the Palazzo Barberini show is, albeit with some differences, the same one that was hosted in the summer of 2017 at the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, which offered support for the creation of the Roman exhibition.

It lacks some works that could have provided a more complete overview (above all, the celebrated Vertumno), but the essays in the catalog make up for what is missing in the rooms of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica at Palazzo Barberini (and for that matter, it can be added that the last major exhibition on Arcimboldo was six years ago, so it made little sense to reintroduce it: the one in Rome is a smaller, but very thorough and interesting review). There are no scholarly novelties, but the exhibition is based on an excellent popular project whose main strength is the historical and cultural contextualization of the entire itinerary: almost all the comparisons are punctual, the information offered to the visitor is accurate, and the itinerary never sags in quality. And despite the fact that it is an exhibition on a popular artist, one does not have the feeling of visiting a blockbuster: the approach is typical of a research exhibition, although it is a popular exhibition, whose quality is assured by the good work done by the curator, a great expert on Arcimboldo and director of the Picture Gallery of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and by the scientific committee that brings together several scholars of the period. All in all, the Arcimboldo exhibition combines an evocative journey inside the ingenuity and works of the Milanese artist, enhanced by a modern layout that ensures good readability, with an immersion in the history of late 16th-century culture, told in clear and compelling tones: features that combine to make it a review sure to appeal to all kinds of audiences.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.