Time to climb from the Blue Venus beach to Villa Marigola (a couple of hairpin bends under the holm oaks, asphalt road with strategic bends to offer escapes in case of two-way crossings), time to look at Lerici from the height of the villa’s Italianate garden (magnificent twentieth-century addition), and immediately one is hit by the thunder, the roar, the roar of Archangel Pebble’s Piccolo animismo , set up in front of the’entrance of the gleaming seaside dwelling, in front of this textural dream of sky, boxwood, and salt that will be disturbed, for a couple of weeks, by the obstruction of the gigantic stainless steel box, by the clutter of this installation imagined almost fifteen years ago for an exhibition at the MACRO in Rome and then becoming one of Sassolino’s signature works . It is a large metal volume, three meters tall and four meters wide. Seemingly inert, were it not for the tube that creeps inside the steel and is supposed to suggest the approach of some movement. And, in fact, the tube serves to initiate the process of inputting and subtracting pressurized air, so that the plates that give form to the sculpture are constantly deforming and transforming: the movements of the material cause rumblings capable of overpowering any voice, any sound.

One could say that the miracle of Archangel Pebble’s work, the miracle that pervades perhaps his entire production, is all in this dynamic of opposition between what is seen and what is not seen. Between the apparent fixity of matter and the forces that stir within it. Christophe Tarkos, who is among the most original, most underestimated and most misunderstood poets of the last decades, when he wrote Le petit bidon in 2001 had given soul and verb to an image that, reread in retrospect, appears as close as possible to Sassolino’s Little Animism : Tarkos spoke of a jar, an empty, normal oil can, resting on a table, still, but “dedans il y a de l’air / et dans l’air par contre il se passe beaucoup de choses dans l’air / il bouge / l’air bouge dedans le petit bidon [...] l’air n’arrête pas de tourbillonner dedans le petit bidon / il se passe beacoup de choses dedans le petit bidon [...] il y a des évènements de mouvements de l’air qui bouge / et qui va taper contre le haut du bidon.” Little Animism seems to be a translation of Tarkos that has become matter. And what might seem like noise to everyone, for Archangel Pebble is a song. Every matter has its own way of singing, the artist explains to the squad of journalists summoned for the preview of Fratture armoniche, the exhibition, curated by Carlo Orsini, that will fill the nineteenth-century rooms on the main floor of Villa Marigola until Aug. 8. Praise be to those who chose the title, praise be given to the splendid oxymoron that could be used to catalogue even what is not in Lerici, to classify the production of an artist who came to art from mechanical engineering, to reveal the essence of the work of a demiurge who gives forms to what cannot be seen.

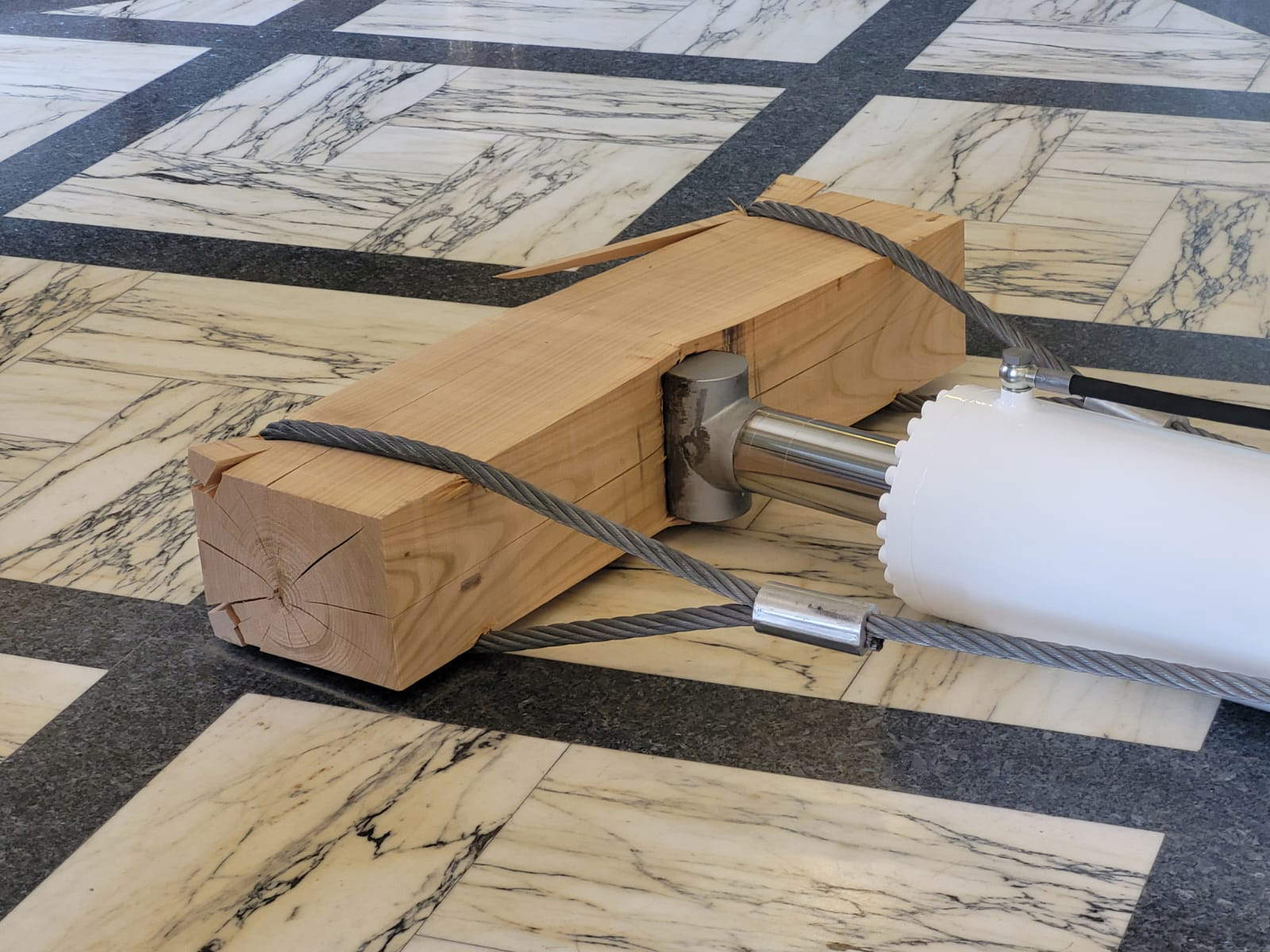

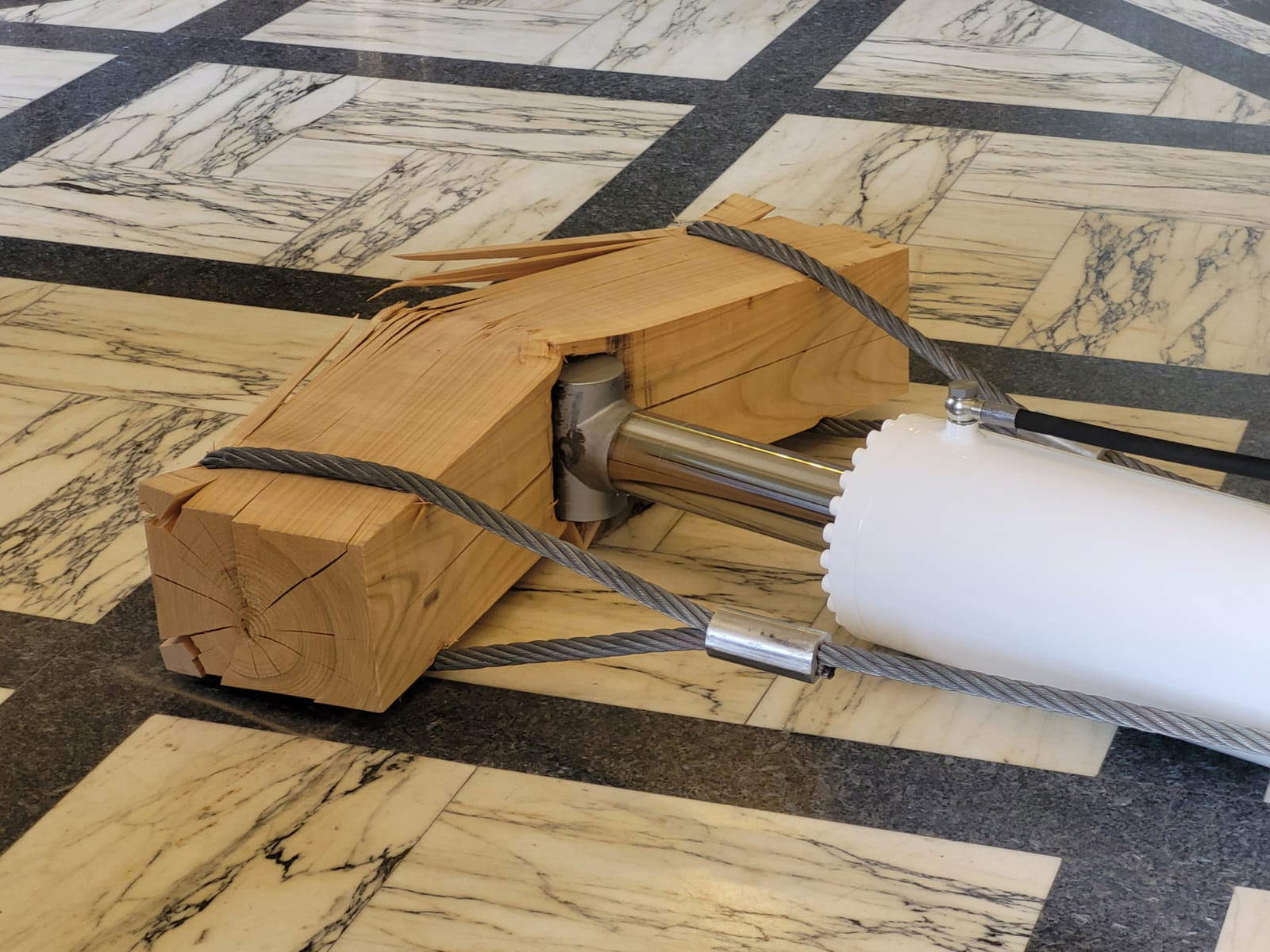

Every matter sings in its own way and, indeed, follows its own score. Sassolino likes to repeat it while showing Random Violence (2008-2016), which is among his best-known works: a hydraulic jack, to which a thick block of wood is attached (almost identical, moreover, to the one that was the basis of Carl Andre’s modular sculptures) by means of a pair of sturdy steel cables, is activated and begins to press against the beam. Slowly, but with a continuous motion. The piston head hits the wood, the first creak is heard. The wood resists. The jack continues to press against the wood. At first it leaves a few dents. The dents then become scratches, chips, wounds, cracks, splits. The wood is slowly deformed, torn apart, destroyed. What remains, in the end, is a stump bent in half, with the flakes facing outward, a completely different aesthetic object than the original one. And throughout the process, the wood sings. To each essence its harmony, its wheeze, its agony more or less slow, more or less violent. Cherry, walnut, chestnut. One wood splits softly and its song dies away suffering, suffocating. Another dies instead in a sudden, dramatic, spectacular explosion.

To a first-time viewer it might give the idea of being a perfectly useless machine, devoid of any practical purpose, engaging in a sterile effort, producing nothing but waste to be disposed of at the end of the performance. And indeed Random Violence is a perfectly useless machine, devoid of any practical purpose, engaging in a sterile effort, producing nothing but waste to be disposed of at the end of the performance. Jean Tinguely, another who built useless machines, said that the machine is a poetic instrument. In Archangel Pebble’s work, the poetry of the machine becomes severe, physical, ruthless. It is an unstable synthesis of matter and movement, destruction and mechanics, silence and spectacle. In some ways, Sassolino could be considered a post-human, post-industrial Tinguely who decided to assign matter an active and autonomous role: where, say, an Alberto Burri listened to the crackling of fire and let matter speak for itself, Sassolino, equally eager to grant matter a word, reveals its impact, its failure, the force that no one can contain, stages rupture as a mechanical process, constant and inevitable, in order to convey the idea that matter has a force capable of escaping human control. A force that finds flesh and further substance in an aesthetic of tension evident where the concept becomes form: think especially of the pressed papers (in the exhibition there is one, White Resistance, from 2023), works that seem almost to offer a body to Spinoza’s principle of self-preservation ("Conatus sese conservandi primum et unicum virtutis est fundamentum: the effort for self-preservation is the first and only foundation of virtue) and at the same time they revive the lesson of John Anselm, who was convinced that a work was both motionless apparatus and living tension (1968’s Torsion comes to mind), convinced that a work was also the instrument for expressing those forces that direct, govern, establish the laws of existence, those energies that reveal themselves without ever showing themselves.

The entire Lerici exhibition is after all built around the idea of the existence of a state of tension that runs through all things. No particular novelty, so far: we are talking about one of the pillars of Archangel Pebble’s entire poetics, we are talking about the foundations of a research that has always explored the state of matter taken to its extreme limits, through tensions or pressures, to the point of making it almost collapse, of destroying it. Sassolino’s work, in its purest essence, is sculpture deliberately deprived of its centuries-old status : it is an unstable temporary body charged with invisible forces. In one of his articles, Manganelli said of Hokusai that each of his characters was not so much that precise character, but rather a comprimario of the latent story that the artist’s sign carried, and that each of his works was the result of an “occult encounter” between “dynamics, even violence, and stillness, pause.” Hokusai’s painting was, in other words, “very clear and occult.” And one could give Manganelli the trouble of taking this happy expression away from him to attach it, as if it were a label, to Sassolino’s sculpture as well. Archangel Pebble’s is also an art of contrasts, of even overt oppositions: it happens, in certain works such as Geography of Conflict, a work in which a number of marbles of various origins (a Brazilian sodalite, a portoro, a Carrara statuary, a bardiglio and others extracted from quarries scattered all over the world, some of them located in the territories of countries at war, as the title suggests) are held together by a vise that tightens and compresses them, but they could also fall at any moment.

One feels a frank, sincere, perhaps even well-founded awe when passing by certain of his works. Take, for example, Le cose facili sono le cose più difficili, a 2019 work: a sheet of glass held in tension by a steel element, bent to form a curve almost to the limit of its tolerance (one never ceases to admire the calculation and research work to which Sassolino, as an expert mechanical engineering enthusiast, continually subjects the product of his hand). We cannot know whether the glass may give way and shatter in the span of a few seconds or in who knows how long. Sassolino’s art is, after all, also controlled danger, challenge to the limit, a system that is on the verge of collapse, a threshold that must not only be observed but also listened to, waited for, even feared. The same applies to his most recent work in the exhibition, Suspension of Choice, a glass jar holding a boulder: one cannot know how long the small jar will be able to support the weight of the stone. Archangel Pebble’s strains are tools for measuring the limit.

It is nothing new, it has been said, that an exhibition of Archangel Pebble tends to bring out what is essentially a foundation of his research, with all its implications (the small catalog that accompanies the exhibition, one of the rare contemporary art texts written in formulas that are comprehensible even to those at home who do not have their library shelves all occupied by Derrida’sopera omnia , lists some of them: “the viewer is prompted to reflect on the concept of vulnerability and the transience of things,” “the movement of physical forces becomes a metaphor for change, continuous evolution and the life cycles of materials.”) The uniqueness of the exhibition lies above all in the comparison between the works and the rooms that house them, the neoclassical rooms of a 19th-century villa that juts out over the Gulf of Poets. A choice that could cause everyone some form of disorientation: This applies as much to those who know Sassolino’s works, who are used to seeing them in other contexts, as it does to those who see them at Villa Marigola for the first time (an eventuality that is anything but remote, since the exhibition is organized as part of a musical event, the Lerici Music Festival, which only a year ago opened up to contemporary art, making use of the collaboration of Galleria Continua). It is a happy choice, however, and not only because on the Gulf shore the public is granted the opportunity to see the product of one of the most interesting geniuses that Italian art has been able to express in recent times. The reasons are essentially two.

The first: space amplifies Archangel Pebble’s reflection on time. Villa Marigola carries with it two centuries of history that has settled. Architecture, changes of use, restoration, the signs of time that its rooms reveal. Time for Sassolino is not only duration, also because duration is not always immediately visible (one appreciates it especially in Random Violence), but it is also, and perhaps above all, critical instant. And so, inside rooms like these, it is perhaps more spontaneous to wonder how long a condition that is stable only in appearance will last, since the rooms of a villa with two centuries of history conceal a time that is subterranean, tense, threatening, and that above all emerges as an active force: that force, present and destabilizing, with which Sassolino’s works are charged is the same force that has transformed the mansion in its two hundred years of history.

The second: in the space of Villa Marigola, Archangel Pebble’s work opens up to a bizarre, unusual geography of ruin. Ruin is a physical and aesthetic condition that has always fascinated us. And Villa Marigola is nowadays drawn out, it is a living space, a bustling place that knows no rest: nevertheless, the mansion witnesses a silent decay, the passing of time, oblivion, if only the loss of memory of the use of its individual spaces. The marquises Ollandini who had it built are dead, their villa in Sarzana is in ruins, the nobles who inhabited it are dead, the artists and men of letters who stayed among these rooms are dead. There is a ruin that is not only that of the walls and plaster, and that can be breathed even where the state of preservation of a building borders on perfection. Sassolino’s works in here evoke ruin not only as a material outcome, as a moment when something breaks down, but also as a process in the making: each of its deformations, each of its crushing, each of its pressures is a slow and inevitable movement that recalls the inevitability of ruin. Time is erosion, it is destructive force, and ruin is its product: there is, therefore, a common destiny that binds the rooms of the villa to the matter of Sassolino. Only the degree of brutality of the language changes.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.