Until Jan. 6, 2022, the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (MANN) is hosting Gladiators, the exhibition that, combining archaeology and technology, will tell the story of the myth of gladiators who competed in arenas. The scientific project of the exhibition, curated by Valeria Sampaolo (former curator at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples), and coordinated by Laura Forte (MANN Exhibitions Office Manager and MANN Photographic Archive), unites Italian and foreign institutions under the legida of a shared path of knowledge. Presented today, the exhibition will open as soon as anti-Covid restrictions are removed.

At the center of the exhibition on gladiators are one hundred and sixty artifacts that, in the Salone della Meridiana, make up an itinerary divided into six sections: “From the funeral of the heroes to the duel for the dead”; “The weapons of the Gladiators”; “From mythical hunting to venationes”; “Life as Gladiators”; “The Amphitheaters of Campania”; and “Gladiators ’from all over’.” An integral part of the itinerary is the seventh technological section, which, titled Gladiatorimania and concentrated in the Museum’s New Wing, is intended to be an educational and informative tool to make the exhibition’s various themes accessible to everyone, adults and children alike.

“Idols of the crowds, coveted by women and protagonists of historic rebellions, gladiators were kissed by a fame that already in their time crossed the boundaries of the arenas and that over the centuries has further magnified,” explains MANN director Paolo Giulierini. “Just think of the many films that have made their stories spectacular or the role that the term itself has assumed in our vocabulary and everyday life. How many times have we called ’gladiators’ the idols of sports and soccer in particular? And ’Gladiators of our time’ are certainly brave women and men who strive to bring noble missions to success, first among them the health workers fighting Covid-19. The exhibition has the ambition to tell not only the myth, but also the human dimension of the gladiator: it does not hide its harsher elements, but places them in a broader framework, revealing the men under the helmets and the historical context in which they lived. From a certain point of view, it is the ’most suffering and symbolic exhibition we have done at MANN: like the ancient gladiators, today we all feel a little hurt and suffering. But, taking a cue from their courage and tenacity, we are ready to get back up.”

Gladiators is the result of an inter-institutional scientific network: the first stage of the exhibition was presented at theAntikenmuseum in Basel and was born from the desire to narrate the fortunes of the ancient spectacles in all areas of the Roman Empire; today, the exhibition at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples is enriched by the focus on Campania’s amphitheaters and, again, the interactive slant of Gladiatorimania. Gladiators ’ partnerships also include the Colosseum Archaeological Park, which is united with the MANN by a memorandum of understanding to enhance common cultural programming. Gladiators, moreover, concludes a path of research that has included collaboration with the Archaeological Park of Pompeii to create exhibition itineraries on the links between the ancient city of Vesuvius and the Egyptians, Greeks, Etruscans and Rome: the latter stage is represented by Pompeii 79 AD. A Roman History, being held at the Colosseum Archaeological Park, to which the MANN has loaned a substantial core of important artifacts(you can read Finestre sull’Arte’s review here). The exhibition was promoted with the support of the Campania Region and will have ad hoc insights in the Campania Region’s Digital Ecosystem for Culture. A partner in the exhibition is Intesa Sanpaolo. Accompanying the exhibition is a catalog published by Electa.

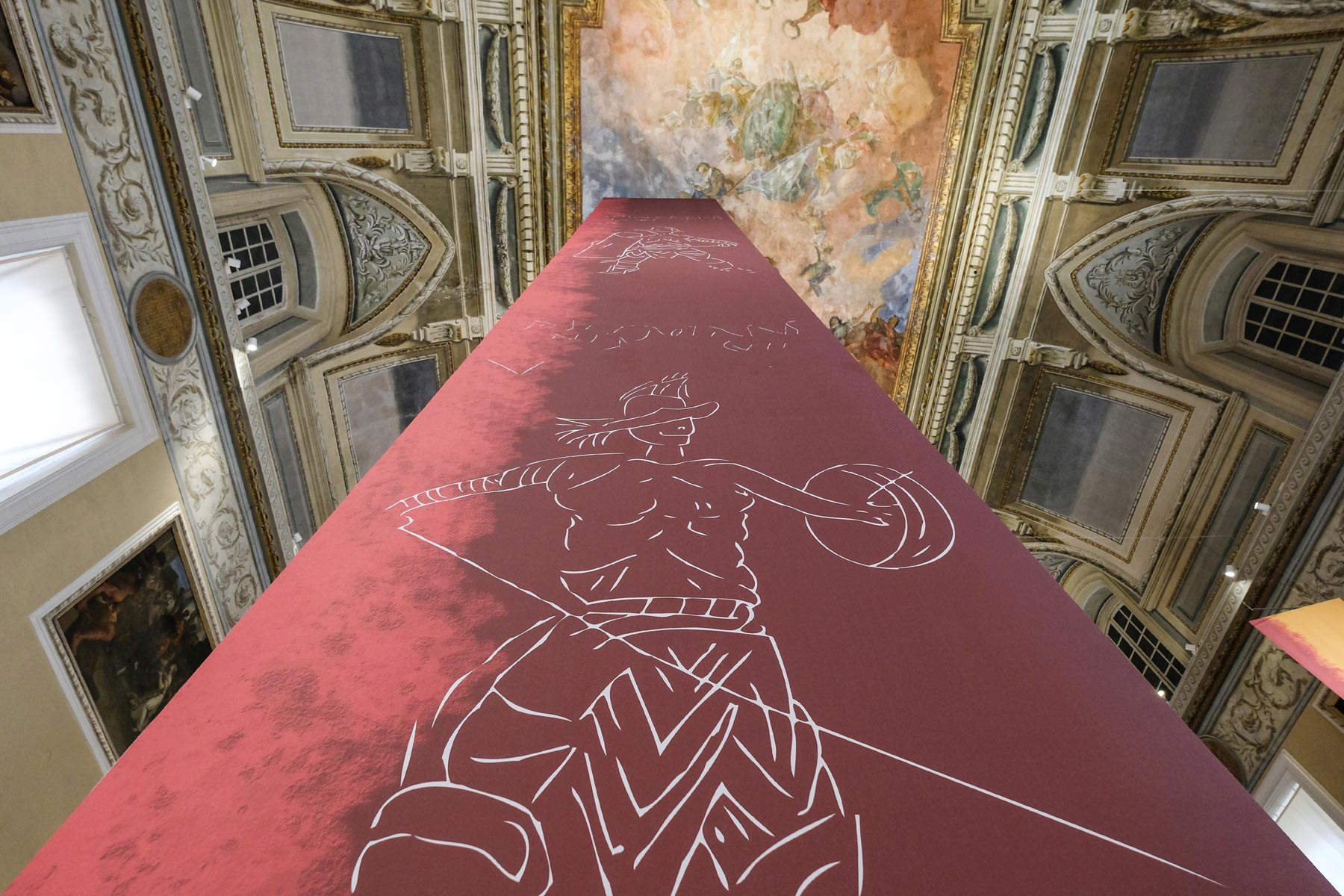

|

| Exhibition layouts. Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| Exhibition layouts in the Salone della Meridiana. Photo by Mario Laporta |

The first section of the exhibition, “From the Funeral of Heroes to the Duel for the Dead,” traces, in the funerary rites and fights in honor of the dead, the elements that constitute the antecedents of the Gladiators’ performances. Among the nine artifacts exhibited in this initial segment of the display, we start with the Vase of Patroclus (340-320 B.C.), belonging to the MANN collections: the crater was discovered by chance in Canosa in 1851, inside a monumental underground burial intended to house the remains of a knight. The slabs from the Gaudo Necropolis in Paestum date to the 4th century B.C.; these are from Tomb 7, among which two depictions stand out in particular: the first scene is a fight between warriors, accompanied by a double flute player; the second is a deer hunt. In this section one can also admire the relief with a scene of Gladiatorial combat (1st century B.C.), found in Rome on the Via Ostiense: the find, kept in the Museo Nazionale Romano and coming from an ancient funerary monument, is put in dialogue with the work of Francesco Morelli, who reproduces the now lost decoration of the Pompeian tomb known as Umbricio Scauro’s. Francesco Netti ’s oil on canvas reflects the contemporary reinterpretation of the myth of the gladiators: in the painting, on loan from the Capodimonte Museum, the depiction of the heroes at the triclinium after the allarena combat.

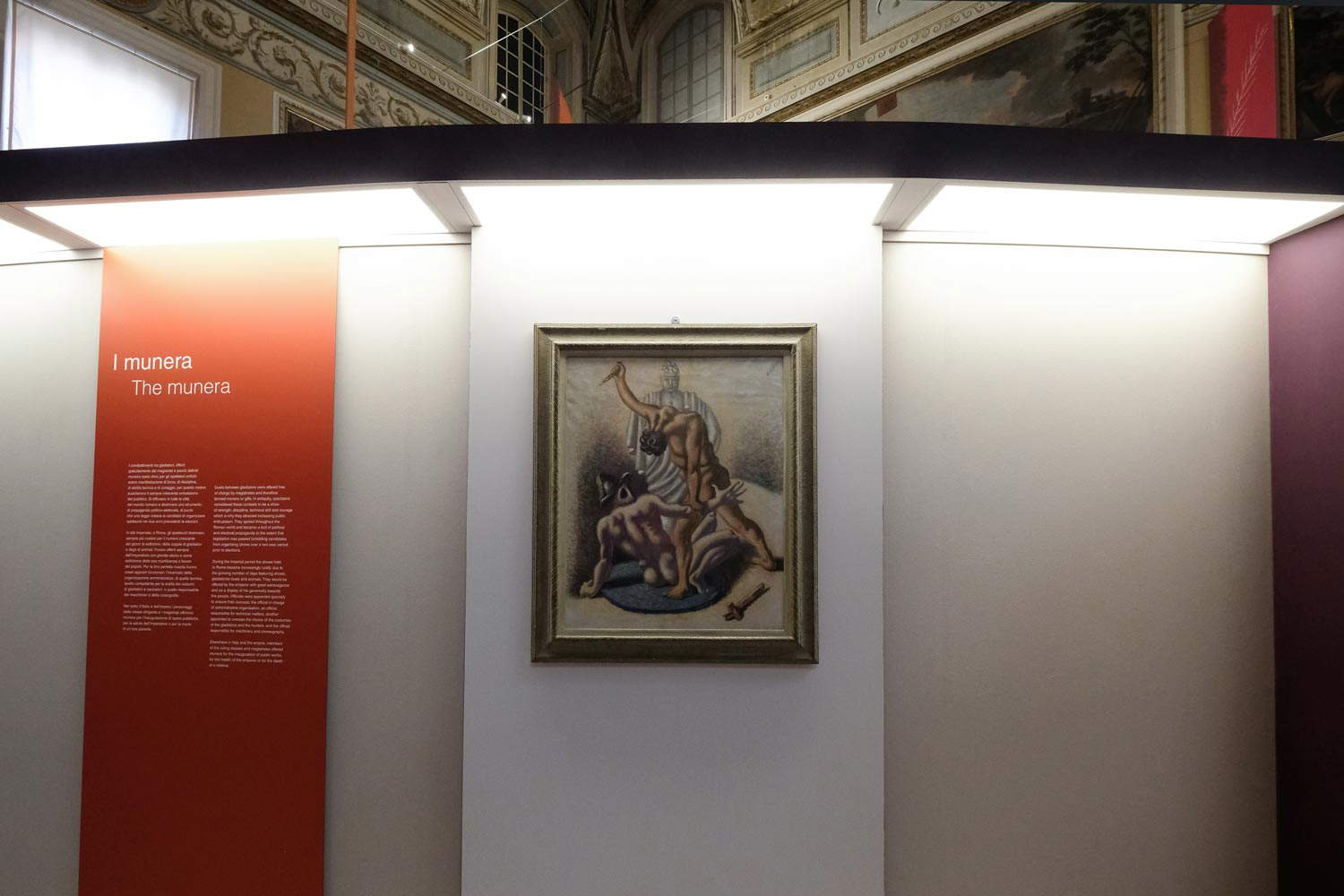

It continues with the second section, “The Weapons of the Gladiators”: not simply tools for clashing with opponents, but a symbol of the ethnic origin and classes of the Gladiators: in the exhibition, it is possible to admire the approximately fifty specimens of the famous collection of weapons, mainly from Pompeii and belonging to the heritage of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. The artifacts (among them, helmets, shields, shields, shoulders, spear spikes, daggers, swords), only sporadically exhibited at the Archaeological Museum in their entirety, will become part of the new and expanded Pompeian display at the MANN. The collection represents the most celebrated collection of Roman weapons that has come down to us since antiquity. Through the often richly decorated artifacts, it is possible to grasp the differences between the different classes of Gladiators. Among the best-known types is the Myrmillon: he wore a heavy helmet, which covered his entire face, attacked with a long sword and defended himself with a wide curved scutum, while his legs were protected with a single schiniere(ocrea), often adorned with mythological motifs. An unfailing opponent of the Myrmillon was the Thracian, whose name still retains the ethnic connotation of one of Rome’s enemy populations: this fighter had a helmet that, regardless of the greater or lesser refinement of execution, featured a crest with a reproduction of a griffin; in the example in the MANN collection, the straight brim and eye opening with small gratings also stand out. The weaponry that accompanied the Secutor was different: he opposed the Retiarius, wearing a rounded helmet (two specimens on display) and a smooth shield so as not to allow footholds in the adversary’s net. Similar to that of the Secutor is the armor of the so-called Provocator: he wore a smooth helmet with a rear neck guard, wielded bladed weapons and challenged almost exclusively with the same category of fighters; not to be missed in the exhibit are two helmets with eagle, bust of Hercules, mask and with gladiator between helmet and sword. Finally, the Reziarius fought by lifting a net equipped with weights to wrap the challengers: the armor specific to this type of gladiator included the galerus (protective plate on left shoulder, extended to protect the throat), which we find in the exhibition with interesting specimens (galerus with bust of Heracles and cupids and with dolphin, trident, anchor, rudder and crab). In the section, there are also several artifacts related to the musical moments that accompanied the Gladiator contests: among them, again from Pompeii, some cornua from the first century AD and a modern copy of a double tibia from a first-century AD original (the loan is from the Museum of Roman Civilization). In dialogue with the collection of weapons from Pompeii, there are a number of reliefs: the scene of combat between Gladiators, on loan from the Archaeological Park of the Colosseum, dates from the end of the 1st century BC; from the Capitoline Museums comes the depiction of the clash between Retiarius and Secutor. Finally, characterizing the section is an unmissable foray into contemporary art: the genius of Giorgio De Chirico is entrusted with the evocative pictorial representation Gladiators and Arbiter III (1931, Udine, Casa Cavazzini).

The third section, “From Mythical Hunting to Venationes,” delves into the venationes, which represented the opening moment of gladiatorial shows: instituted in 186 B.C. by Marcus Fulvius Nobiliorus and remained in vogue until the sunset of the Empire (the last such show was organized under Theodoric in 523 A.D.), hunts in arenas had a profound political, cultural and symbolic value. The venatores, in fact, embodied the virtues of tenacity and courage and engaged in confrontations with animals after hard training.It is estimated that about two and a half million beasts, which came from different regions of the empire (North Africa, Asia Minor, Germany), were killed in more than five centuries of fighting. Peculiar was the setting in which the venationes took place: real spectacles were set up in the arenas, with backdrops and settings of historical and mythological matrix; the ferocious animals, with which the hunters usually competed, were buffaloes, bears, lions and elephants. Among the seven works on display in this section of the exhibition, the Campana slab with a scene of venatio in the circus (National Roman Museum) stands out: the work, which is part of a frieze made between 40 and 60 AD, depicts a hunt in the Circus Maximus, recognizable by the column topped by a statue and other architectural elements. In the display, it is also possible to admire the pluteus with the hunting of Meleager and Atalanta (2nd century AD, Campanian Amphitheater of Santa Maria Capua Vetere), which evokes the mythological substratum of the spectacles, as well as the graffito with animals, from the Roman excavations of Aventicum and preserved in the Musée Romain in Avenches. From the archaeological site of Augusta Raurica and the holdings of the related Antiquarium was loaned the interesting find of a bear skull (2nd cent. AD), while later are the cup with damnatio ad bestias scene (second half of the 4th-5th cent. AD, from the Museum of the Crypt of the Roman National Museum) and the diptych of Flavius Areobindus, whose term post quem is 506 AD (the work is kept at Zurich Schweizerisches Landesmuseum).

In contrast, the section on the “Life of the Gladiators” recounts the more human dimension of the protagonists of the famous fights in the imperial arenas. In this section, artifacts make it possible to reconstruct the characteristics of the person under the helmet, starting with some and specific aspects of the dimension furthest from the arena: feeding; medicine and surgery; the individual and death. In the exhibit, therefore, are some archaeobotanical artifacts from the MANN: these are panicum, barley, field beans, lentils, and spelt, all from Vesuvius. The Gladiators had a diet very poor in animal protein and based, rather, on grains and legumes: not surprisingly, the fighters were called hordearii, barley eaters. This type of diet seemed to promote the formation of body fat, which could better protect against the violent attacks of enemies; alongside the foods, according to Galen (a physician in a gymnasium of Gladiators), a tonic mixture of ashes and bones was added, to provide good stamina in duels. Personal care also came, of course, through remedies to soothe wounds inflicted during fighting and venationes. In the exhibition, there are a number of evocative artifacts, testifying to the most popular medical and surgical practices: among the specimens on display, it is necessary to mention the decorated lid of the medicine chest (Herculaneum, 1st century AD), the bronze medicine chest, the pouch with instruments, the dentist’s pliers, the surgical forceps and suction cup, the phlebotomist’s phlebotomus and three decorated scabbels with gladiators (all the latter specimens come from Pompeii and can be dated to the 1st century AD). In the section, an in-depth space is devoted to the Gladiator narrated through inscriptions and funerary reliefs: from theAntikenmuseum of Basel comes the stele of Peneleos (3rd century AD), while from the Capitoline Museums comes on loan the stele of Aniceto (2nd century AD); finally, it was found in Pozzuoli, but belongs to the collections of the MANN, the funerary lyscription of Myrmillon Paeraegrinus (201-300 AD). There are two curiosities in this segment of the display: Gladiators houses, in fact, three of the skeletons found in a vast necropolis of gladiators brought to light in York; the remains, which belong to men of different ages (20/20 years, 18/25 years and 36/45 years), also return a number of useful elements for the reconstruction of the area of origin and diet of the fighters. Also completing the section is some gold jewelry found in the Gladiator Barracks in Pompeii: among the jewelry, two gold rings stand out, as well as bracelets of folded foil: according to scholars, the ornaments belonged to one of the many fugitives who took refuge in the Quadriporticus of the Theaters to ward off death. Gone, now, is the romanticized , if suggestive, view that attributed its owner to a woman, believed to be the lover of a Gladiator.

The section “The Amphitheaters of Campania,” through models, graphic apparatus and digital media, represents a focus on ancient amphitheaters. Dating back to the end of the second century BC. C. the realization of the buildings intended to host gladiatorial shows: precisely in Campania, the first stable constructions were erected for the munera until then held in the Forum. For the first time, thanks to a project carried out by Altair 4 Multimedia, the sequences of frescoes that adorned the Amphitheater of Pompeii have been virtually reconstructed. The paintings, discovered between 1813 and 1815, adorned the dividing wall between the arena and the building’s tiers of seats.The works did not have a long life following their discovery, because, after initial damage by unknown persons, they finally collapsed in 1816. We owe the faithful succession of the six figured panels to Francesco Morelli, who reproduced the details with his own tempera paintings displayed in the exhibition: among the individual representations, there were eight sections painted in scales and faux marble, separated by herms, Victories on globes and metal candelabra on a red background. Suggestive was the iconography reproduced in the ancient Amphitheater: in the frescoes, there was the opening scene of a munus, the four animal hunts and the two gladiators placed on either side of the entrance. Based on Morelli’s works, Altair 4 Multimedia’s reconstruction starts with a virtual comparison between the Amphitheater as it is today and the building of the past: it is a bird’s-eye view that accompanies the progressive digital recomposition of the building, “unveiled” also in its own connection with the adjacent urban context. Still dedicated to Pompeii, is the cork model of the Amphitheater, made by Domenico Padiglione at the beginning of the 19th century and restored precisely on the occasion of the exhibit on the Gladiators: the prototype is placed in dialogue with the famous fresco of the fight between Pompeians and Nocerini, a work belonging to the MANN collections. Also on display are insights dedicated to the Amphitheater of Santa Maria Capua Vetere, presented thanks to a reconstructive model. Still, an ad hoc space is reserved for the prototype “elevators” that were located in the Amphitheater of Pozzuoli and acted as freight elevators to transport the fairs from the basement to the arena. On video, a journey to discover the amphitheaters that also dotted the interior areas of the region. Then there is a scientific and archaeological “tribute” to the Roman Flavian Amphitheater: in fact, it is possible to admire some fragments of the marble decoration of the Colosseum, including the remains of a balustrade with a crocodile head, the locum with the inscription “Sereni” and the transenna with cornucopia (all these finds can be dated between the 3rd and 4th centuries AD).

Finally, the section “Gladiators ’from all over’” recounts the myth of gladiators: as early as antiquity, the fortunes of these fighters were “translated” into the decorative apparatus (mosaic and parietal) and furnishings found in Roman homes. This section of the exhibition follows, thus, the fortunes of the Gladiators between the domestic dimension and art: a number of artifacts from the MANN collections are included, such as the three Pompeian oil lamps with representations of gladiators (from Pompeii, 1st century A.D.) and the small bronze statue of a gladiator fighting against his own phallus transformed into a panther (from Herculaneum, 1st century A.D.); also suggestive are the three Pompeian cups with venationes and duels between gladiators (1st century A.D.). From the archaeological site of Aventicum (Musée Romain, Avenches) come the statuette of Secutor (2nd cent. AD), two fragments of decorated glass (2nd cent. AD) and the modern copy of a handle (3rd cent. AD) with Secutor and Retiarius; on loan from the Antiquarium of Augusta Raurica, among other finds, are a helmet-shaped oil lamp (2nd cent. AD) and a plaster with graffitied gladiator (2nd-3rd cent. AD:), while from the Antikenmuseum und Sammlung Ludwing in Basiliea two oil lamps (late 2nd-early 3rd cent. AD) and a cup with Gladiator fights (2nd cent. AD) arrive on display. The highlight of the exhibition is the Augusta Raurica Floor Mosaic (late 2nd century AD): the work was discovered in 1961 during excavations in Insula 30 of the Augusta Raurica archaeological site and surprised the discoverers by the extent of its surface (6.55 X 9.8 meters). The Augusta Raurica Mosaic is on display at MANN, as well as in the first stage of the exhibition at the Antikenmuseum und Sammlung Ludwing in Basiliea, after the restoration campaign on the find. The masterpiece has never been presented in any exhibition in Italy.

|

| Gladiator helmets. Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| Helmet and shield . Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| Slab from the Necropolis of Gaudo. Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| Weapons of the gladiators. Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| Skeletons from York. Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| The floor of Augusta Raurica. Photo by Mario Laporta |

The exhibition also presents an “off” itinerary called Gladiatorimania that, before or after visiting the display in the Salone della Meridiana, allows visitors to tell the story of the Gladiators also thanks to the most innovative communication technologies. From the ground floor of the New Wing of the Museum, passing through an entrance that re-proposes the suggestions of the access in an Amphitheater made by Scenografie Rubinacci, it is possible to follow, in two levels, a narrative centered on different themes: the training; the diet of the Gladiators and the food of the public; the combat; the armors, the places of the games and the venationes; the comforts in the amphitheater; the care of the body in the amphitheater: between perfumes and wounds; the fortune of the Gladiators; Gladiators at play. Marking the journey, precisely to define its popular nature , are the drawings, signed by Mario Testa (Italian School of Comix) and included in the Panini publication dedicated to the Gladiators.

The journey begins from the training of the ancient fighters, from their training: on display are reproductions of weapons, the diorama of the gymnasium of Lentulus Batiatus in Capua and the one with figures of gladiators in the gymnasium before the fight (diorama realization: Ars Invicta). Also on display are two cruets of oils with strigil for cleansing the body after training (Rancati). Thanks to monitors placed in the exhibit, it is possible to dwell on a short computer graphics film with the reconstruction of the Schola Armaturarum (the video is by architect Marco Capasso Marco Capasso Studio Creativo). In the cavedium, the visit continues with the suggestion of the reproduction of the interior of the Quadriporticus of the Theaters of Pompeii, the training place of the gladiators.

We then come to the diet of the gladiators and the food of the public: on display is a video on the daily life of the gladiators, in which the elements of continuity with the diet of today’s athletes are analyzed. In the panels in the hall, there is also a focus on the food of the audience, before and during the performances. Then there is also a small olfactory station, set up with stage furniture by the Rancati company, which, through samples for the audience, allows them to perceive the aromas of some of the foods that, in all areas of the Empire, formed the basis for preparing the body for training. The third part, on combat, reproduces the Gladiators’ classes thanks to Luca Tarlazzi’s drawings and 3D films to learn the secrets of gladiatorial combat by Professor Aldo Zappalà. And then again the re-proposition of Roman furnishings in the amphitheaters and the model of a horn, also provided by the Rancati company: thanks to a small projection room and the extensive educational apparatus, declined in panels and reconstructions for the public, it is possible to dialogue with the most important archaeological contents of the exhibition, with a path designed for adults and children.

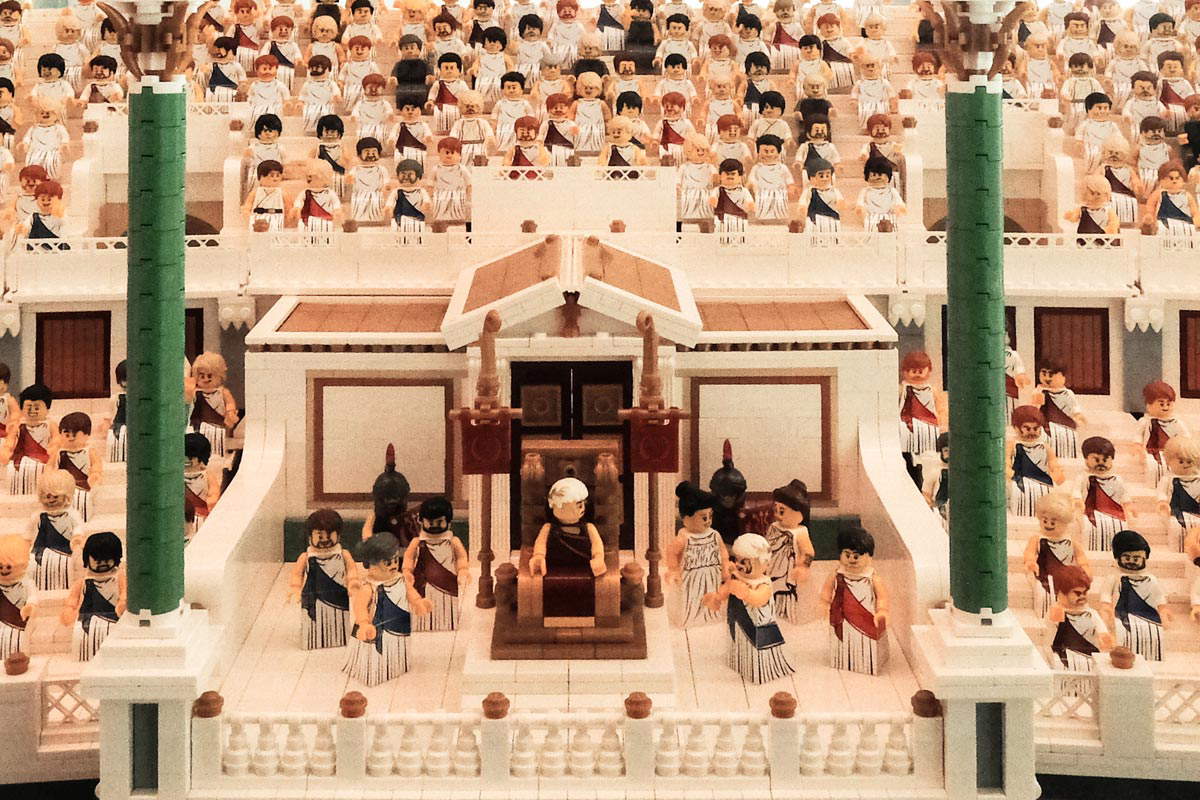

The fourth part, on armor and the places of the games, brings on display a copy of a bronze gladiator helmet (Fonderia Nolana Del Giudice), which can be touched by the public to understand the consistency and workmanship of a symbol of the Gladiators’ armor; on display, captions in Braille to facilitate the understanding of the piece on display also by the visually impaired and blind (by the Educational Services of the MANN). Available is the projection of a film showing the stages of construction of the gladiator helmet: from the scanning of the original work to the bronze casting of the copy, including the three-dimensional reconstruction of the helmet’s decorations (the short film is edited by Prof. Aldo Zappalà). Also featured are 1:1 scale armor reproductions (Silvano Mattesini) and Lego amphitheater dioramas (Antonio Cerreti). Dedicated to the buildings that hosted performances are the 3D video on Campania’s amphitheaters (Aldo Zappalà) and the film The Paintings of the Pompeii Amphitheater (Altair 4 Multimedia). Also available are insights into the mechanism for transporting fairs to the amphitheater arenas during venationes and the types of animals used in the games (by the Naples ZOO). The fifth part is on the care of the body in the amphitheater: also present, thanks to the network with The Museum of Sanitary Arts of Naples directed by Professor Gennaro Rispoli, is a corner dedicated to the origin ofmedicine with a focus on the treatment of gladiators’ wounds and traumas: the educational section includes reproductions of surgical instruments from ancient times compared with modern instruments, in order to fully understand their evolution.

We then come to the section on the fortunes of gladiators, the most cinematic section of the off itinerary: on display, for cinephiles and others, is also the shoulder cover used by Russell Crowe in the film The Gladiator. Finally, with the last part, “Gladiators at play,” we enter the playful dimension of the exhibition: in the hall, self-supporting gladiator silhouettes are set up (in the background), portrayed in the drawings of the Italian School of Comix, and it is possible to take a picture next to the image of the fighter; again, a blackboard with large sheets of paper gives the opportunity to draw, letting the imagination of young and old run free. Finally, a novelty: the game The Archaeological Chess of the MANN, created by studio 3DnA s.r.l (Alessandro Manzo, Fabio Tango, Stefano Ciaramalla, Mariano Abbate). The game pieces consist of images of the artifacts on display at the museum. Also presented here is a tactile prototype with braille captions by MANN Educational Services based on a design proposal by Ludovico Solima (University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli). In the Ambassador room on the ground floor of the museum, the video Gladiators of Paper, created by two artists (Sara Lovari for the paper costumes and Mauro Maurizio Palumbo for the choreography), is projected: it also highlights the fragility, behind the armor, of the characters who, often, were forced to become gladiators; also on display is the paper armor used for the short film. The installation of the Gladiatorimania section is signed by architect Silvia Neri with set designer Paolo Pariota; the graphic design is by Francesca Pavese with Sintesi Studio. Texts are by Valentina Cosentino and Rosaria Perrella. The multimedia content, as well as the virtual reconstructions of the Amphitheater of Pompeii, were included as part of interventions promoted under the PON on digitization.

|

| De Chirico’s gladiators. Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| Detail of a gladiator’s helmet. Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| Daggers and swords. Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| Slab from the Gaudo necropolis. Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| Gladiatorimania section. Photo by Mario Laporta |

|

| The Gladiatorimania section. Photo by Mario Laporta |

On the occasion of the exhibition, the publishing house Franco Cosimo Panini Editore is publishing the illustrated story Una giornata da Gladiatore. The publication, dedicated to children and teens aged eight and up, is the result of a project and idea of the Educational Services of the MANN (Head: Lucia Emilio/ staff: Elisa Napolitano and Annamaria Di Noia), with the collaboration of the Exhibitions Office (Laura Forte); the illustrations are signed by Mario Testa for the Italian School of Comix. The narrative develops on different planes, which are intertwined thanks to the drawings and the proposal of educational quizzes and themed games: the frame of the story is represented by the adventures of theeditor Marcus Lucretius Rufus, organizer of Gladiator shows. In a typical day, the character must select the combatants, choose and set up lanfiteatro where they compete, arrange moments of musical entertainment and select the fairs for the venationes: during these activities, the protagonist has the opportunity to open real windows of insight dedicated to young readers.

From the classes of Gladiators to the architecture of the ancient amphitheaters, from the type of weapons used in clashes and parades to the fame of Gladiators, the volume intercepts themes that manage to combine only seemingly distant temporal dimensions: among these motifs, which include a reflection on current events, brawls between different supporters during the games and female gladiators. To the reader, it also falls to the reader to enter the links in the story: the pages coloring the venationes, creating your own gladiator with the book’s stickers or the themed crossword puzzle represent a concrete way to learn without giving up the fantasy of play and drawing. The publication is also translated into English.

|

| Naples, a major exhibition on the Gladiators at the National Archaeological Museum |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.