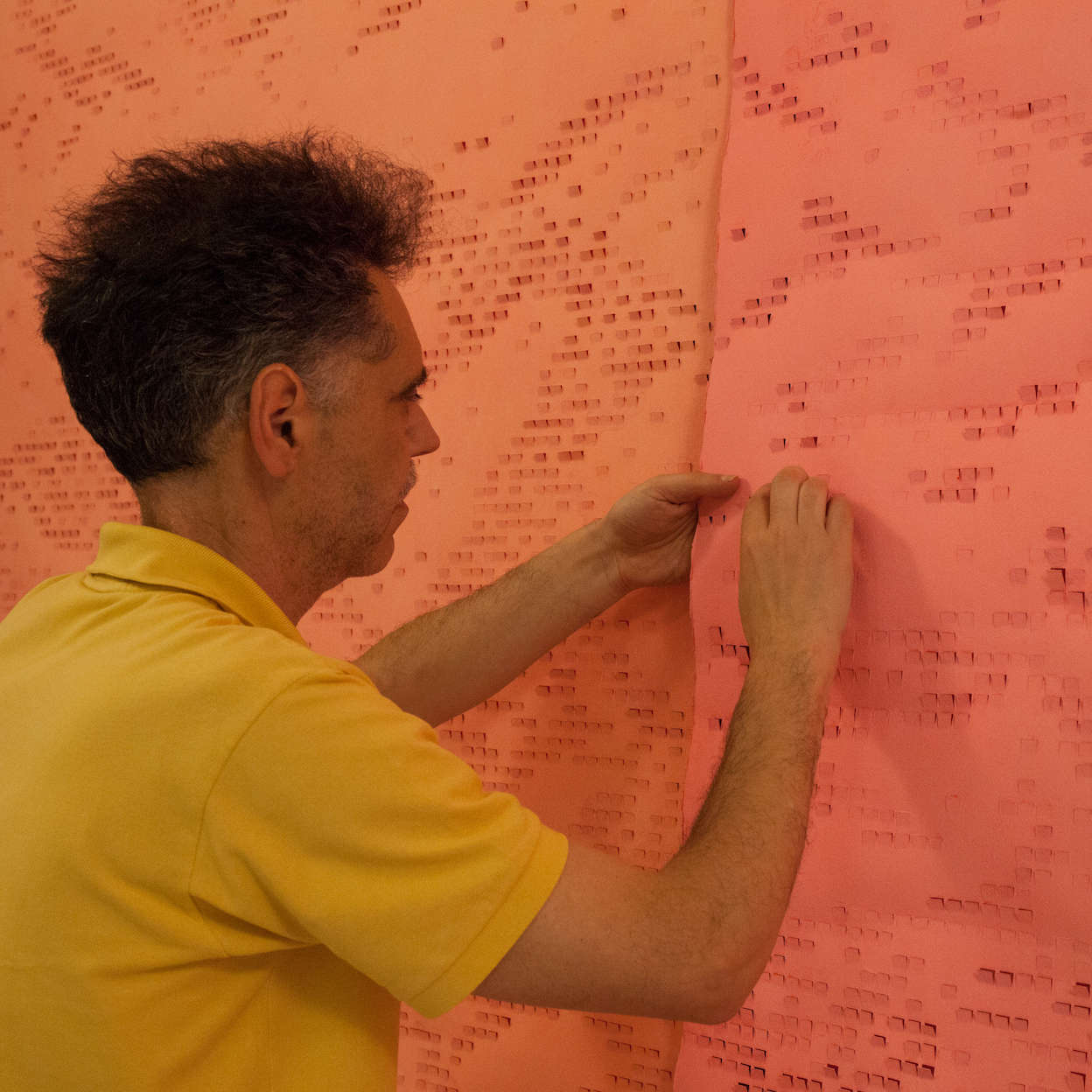

Pierluigi Fresia (Asti, 1962) lives and works in Pino Torinese (Turin). His artistic research, always traceable to the conceptual sphere, is developed through different media - from painting to video, from photography to the use of words - often combined in a multimedia key. Since 1993 he has exhibited regularly in Italy and abroad, with numerous solo shows in prominent spaces such as Galleria Martano in Turin, Galleria Milano, Vision QuesT 4rosso in Genoa and Studio G7 in Bologna. Among the most recent: The Celestial Impotence of Planets (Florence, 2025), On One Way (Turin, 2023), ANTOLOGICA (Innsbruck, 2021), The Speed of Light (Brescia, 2021). His works have been presented in major international contemporary art fairs, including ARCO Madrid, Artissima Turin, Artefiera Bologna, Arteverona, MIA and Miart Milan, Photo Basel and Fotografia Europea (2010, 2015). He also participated in the Gubbio Sculpture Biennale (2006) and the Daegu Photo Biennale in South Korea. His works are part of important public and private collections, including GAM in Turin, MART in Rovereto, and the MET in New York. He has taken part in numerous group shows in institutional spaces and galleries, including Il tempo della comunanza (Saluzzo, 2024), The Family of the Man (Aosta, 2021) and Under The Lucky Star (Genoa, 2012). In this conversation with Gabriele Landi, Pierluigi Fresia tells us about the ideas that sustain his art.

GL. Let’s start at the beginning, an unconscious beginning, which for many coincides with childhood.

PF. Often, in one way or another, you always go back to that moment. Of course, when you are little more than a child, you don’t know what art is, you just feel the urge to make. I, at that age, always had a pencil or brush in my hand and I had to do something: paint, draw. It was an urge to express myself, and that channel seemed the most natural, the most viable. In fact, in some respects, it surpassed even that of speech. Not that I was aphasic, mind you, but I could express and resolve my arguments much better with drawing and painting. Although calling it painting seems like a big word, it was still the mode of expression that was most congenial to me. Then, whether I was actually able to express myself totally in this medium is another matter. You start there, though, and then slowly you realize that it is a concrete thing. It’s not you that’s different from others, it’s a real thing, like for people who have an ear for music or the ease of, I don’t know, dancing or sports. Of course, I grew up in a small town, so it wasn’t all super easy. I don’t want to cloak this part of my life in romanticism: mine was a normal family, my parents were unschooled but they always let me do it and never hindered me. Here, for this I am very grateful to this day.

In some way, did this urgency then also guide your school choices?

Absolutely not. In fact, that was the only aspect that was a bit problematic. I lived in the province of Asti, and there was no art high school there. In spite of the fact that the professors insisted, telling my parents, “This boy has to do the Liceo Artistico,” it was unthinkable as well as impossible for me to go to Turin every day at thirteen and a half years old. So I made another choice, however, I continued on my own, without giving up. I always studied and did my own thing. I enrolled, after high school, in the Faculty of Letters, although I never finished the course of study. I learned to paint as a young boy, from a painter in the village, the kind who used to do prize competitions. I did some as a kid, too; as I’m talking to you, here next to me in the studio I have a medal table full of medals won in those years. These are things that encourage you, yes, and it was a way to see paintings, sculptures, in short, works done by artists who were full of passion if they were amateurs, which was not taken for granted in a small town in Monferrato in the early 1970s. So I used to see them precisely at these exhibitions of amateurs that opened during the village festivals, with the jousting and all that; for the rest of the year there were the frescoes in the parish church. There were no works of art in my house, except for a few prints bought to decorate. Then I started looking at my brother’s books, who was doing art education in junior high school, and so I started to inquire, to read, later to get something from the library, which fortunately the country offered, illustrated monographs, art history books. In short, that’s how it went.

Did you have a first artistic love? Is there something that particularly kindled your imagination or your interest, something you remember in particular?

Well, look, I couldn’t tell you exactly. We go so far back in time that it’s hard to pinpoint a precise starting point. Mine was more of a physical need to use my hands to do something. In the beginning, I mostly drew the landscape I saw, the dog, the cat, the things in front of my eyes. The thing that bothered me most and I avoided above all else was copying. I had friends who copied drawings from others or from books; this irritated me. Not because I thought I was good, or maybe in my naiveté I was, after all, children are conceited, but they should be because they have to demand the most of themselves, to enter and take their first steps into the world outside. Thinking about it now, though, I do remember something specific.... I remember that among my mother’s clients, who was a seamstress, was a Polish lady, a refugee (the Cold War was a concrete reality), who had studied art in Warsaw in her youth. When she would come to Mother’s for her clothes, she would see me there in the corner drawing and I remember her saying, “Ah, this child has a hand!” At that time, my mother knew an amateur painter, to whom I am very close and she is still alive and her name is Mona Lisa, a name a guarantee! She did landscapes, I must say also very beautiful ones, she was inspired by the Impressionists and she had very good taste in her choice of colors. Her paintings were very good landscape paintings, some still life; therefore, my mother sent me to her to learn. I was eight, maybe nine years old. It was she, Mona Lisa, who taught me how to use oil colors, which I did not know. My parents bought me oil paints, palette and a small easel. I went almost every afternoon to her place to paint, I would walk 5-6 km because I lived on a hill. Every once in a while she would take my paintbrush and fix what I was doing, which I admit bothered me a lot. He would say, “No, but do this like this.” I was shy and dumbfounded, I still remember the light in the room at the precise moment when she said that sentence to me: these are footprints in the soul that remain there tracing a path. I remained on good terms with this lady and I love her, she revealed to me the secrets of oil color, of how to mix them, dilute them, spread them, and then the fragrance of turpentine, wonderful memories. That fragrance is still there now, beautiful, gets you in the mood, makes you feel like a painter right away. Eh, that was the beginning, which, as you now realize, was painterly.

You have already mentioned to me your comings and goings between painting and drawing....

Drawing I think is one of the oldest and most mysterious modes of expression of the human being. It is the ability to leave a mark, which then becomes writing, message or figure, it doesn’t matter. Already the finger tracing in the sand for prehistoric man was the beginning of a change, a great change. It is a gesture of awareness, the becoming aware of one’s own existence: it is you individual who draws that mark, it is you who creates it and you create it as you want it to be, making visible something that was not there before and that, thanks to that gesture, manifests and manifests yourself.

Drawing is also present in your current work, isn’t it?

Yes, absolutely. Even in my current work, where I mainly use photography, the composition always starts from an idea of drawing. It is what defines the spatial arrangement needed to achieve the image I have in mind. Even before I shoot, I have to mentally visualize what I want, considering the elements around me. I don’t consider myself a photographer in the strict sense of the word. I’m not someone who does street photography, Cartier-Bresson style, for instance, looking for the decisive moment-assuming it wasn’t then all planned in advance, but let’s pretend it is. I am not one to capture the perfect, unexpected instant that happens suddenly, the unexpected epiphany. This kind of approach implies total immersion in the flow of life, direct interaction with society and what it offers, finding there the subject matter and material to work with. No, that is not my style. Also because often there are people involved, and I don’t photograph them. Sometimes I draw them or paint them, but that’s different. So, utmost respect for that kind of work, really, there are beautiful things that I really admire. But that’s another thing.

Earlier you alluded to the fact that you went to the Faculty of Arts. Often, or rather, I would say always, writing appears in your work. How do you create a short circuit with the image underneath or alongside the text?

Let’s say it is a poetic idea, but also the result of a long process. Actually, when I start a work, there is no predefined link between the text and the image. It is a much longer and more complex work than one can imagine. For example, just a little while ago, while I was waiting for your call, I was working on an image and I was associating texts with it that I had ready-made, not designed specifically for that image. Sometimes they are things written two years ago, sometimes two weeks ago, sometimes the day before. Then I start linking images and texts, a new work of composition begins, where the text, while maintaining its meaning, must also find its spatial match to the image, beyond the content. Next, I begin a work of analyzing the text in relation to the image. I have often realized that it is easy, on a subconscious level, to match a text to a particular image and then realize that it becomes pure caption; then we start over. There are connections, which I try to avoid, otherwise everything falls apart. The text is not explanation, it is not narration of something that without the contribution of the image one would not be able to understand and vice versa. Instead, they are two forms of language that in the work must coexist, cooperate, but remaining absolutely each in its own semantic and ontological groove. I try to generate a bewilderment that I would like to stimulate an entirely mental and new connection in the viewer, leading him to find, himself, a meaning through a hermeneutic path unknown to me. Thus, if the two entities - word and image - do not have immediate and verifiable conceptual connections, the observer finds himself driven by this cognitive hindrance to try and try again in order to derive some connection that has its own, at least apparent, logic. Now, for example, I have in front of me an image of two trees with a sentence that I have attached to them; it may not necessarily be the final version, who knows. Once it is finished, its real completeness will occur when in the person who sees it for the first time it triggers, for the causes I mentioned earlier, a beginning of a story, a narrative of which I am totally excluded and unaware. This idea that my work acts as a trigger for stories that arise, which I do not know, the result of two things put there by chance or at any rate for my own reasons and that’s all, I like and it makes me feel like a collaborator of the beholder. The viewer is not just a passive observer absorbing everything that is put in front of them. And so, in essence, this is the fundamental purpose and, in my opinion, the main sense of what art should be: a tool, an invitation to thought, to reasoning. As long as there is something that makes us think, we can consider ourselves safe, free; when we stop thinking we really enter a tunnel with no exit. Everything in recent years, from the media to politics, seems committed to supinely pushing us toward that abyss.

There is something in what you say that reminds me of Lautréamont’s famous phrase, much beloved by the Surrealists: “As beautiful as the chance encounter between a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table.”

Absolutely. I think of surrealism not so much from the point of view of the image, but rather from the point of view of the mechanism. In my case, this mechanism should not be meaningless, purely surreal and thus remain closed in on itself. I am interested in the viewer finding his own space within the short-circuit that is created between image and text, bringing this short-circuit to himself, to make it become something real or, if not real, at least conceivable, that triggers the imagination. In this way, a kind of “power relationship” is created between the image and the text, that is, a power relationship not to be understood as an arm wrestle, but a relationship nonetheless that is somehow perceived even if not legible in the process that drove it, which I later realized is a private, personal affair that probably also arises from an accumulation of images and texts. Of course, the two things each go to accumulate in a separate container, so there are images that then remain there. I photograph and write, but I never do it contextually. For example, this image of the two trees I took now, but the sentence I’m trying to insert now followed another path and came from another time. Let’s say that when I go out photographing, or even in the studio, that psychological aspect comes into play that makes you love that image instead of another. This is something that happens to many people: there is something that fascinates you and you don’t know why. It must have happened to you too, I don’t know, you arrive at a place, especially in terms of the landscape, and you feel that place speaks to you. It is as if that place possesses a matrix in which you can rest your spirit, your being, and the two match. In that moment and only in that moment is the truth; then if you see it in the afternoon or on another day, it doesn’t work, it’s gone. Even if you don’t know, actually, what has been lost, I think it’s good not to know. Probably -- at least that’s what you think -- that there is something related to the unconscious, to childhood, something you first saw in that certain kind of light, environment and feeling, then you create the trigger. The imprinting of certain images that you always have to go back to in order for the two to go a little bit like rangefinder focus, where two identical images have to match, overlap, be one, the real thing, for a moment and then again disappear in time. Sometimes it has happened to me to pass countless times in front of something or in a place and then to realize only after time that there was something important, even though I did not know why.

It often happens to me, too, that you see things in a place you think you know inside out, and one day you happen to see something you’ve never seen before. Or you see them because you travel the same road in the opposite direction. So as you see different things, you also think of different things, which then, if you will, is all connected. This calls up one of the invisible players in your work: time.

Absolutely. I just can’t disregard time, not because I decided so, but because I feel that way. After all, our existence is based entirely on the temporality of things, their finiteness and epiphany. Time is one of the main reasons why I chose to use the medium of photography: it is made of time and also of light. And speaking of photography, I find it incredibly false, much more so than painting or drawing. It is the most deceptive medium there is. Let’s go back to those two trees in front of me right now: I didn’t plant them, I didn’t look for them. They are there, somewhere in the countryside. I photographed them, but they will never look exactly like that again. All it takes is a gust of wind or a change in that fog in the background. It is trite to say that the photo ’captures’: the photo captures nothing, the photo loses. I have always likened the photographic capture to when Orpheus turns back to see Eurydice as they emerge from the underworld: the moment he sees her, he loses her. And it is the same when you take a photo: you have lost. Yet, this ’losing’ has its own charm. It is the image you are left with -- that paper simulacrum, digital or whatever you want to call it -- of something that no longer is, or is not yet, or maybe will become again, who knows. But every time I look at it, that thing ’is’ again. So, the image becomes part of your personal ’baggage,’ of those archetypal images you have inside. In a way, I could almost say that it is a form of nostalgia for what you love but can no longer recognize, and then you recreate it to have traces, a kind of alphabet to dialogue and explain yourself.

Some time ago I remember asking you about your relationship to your studio, and you had sent me a series of images that somehow showed something that has a lot to do with a kind of archive, there were objects... The idea of the archive or archiving is related to what you were telling me, isn’t it?

But yes, maybe more a mental archive than a physical one, because then from that point of view there I am quite messy; so, ’archive’ is a beautiful word that, in my case, is very messy. But yes, from a certain point of view that is also an archive, that is, here are images like in an archive. The fact that I have archived hundreds and hundreds of photographs, and pages and pages of text, writings, notes, makes it so: this is already archiving to then do something, always something to come. So this is okay, you don’t know what for, but it’s okay, surely there will be a time. Then actually sometimes it happens that these things come up again, I can’t explain why, they are all mind games. For example, I realized that I had photographed a piece of blue fabric that apparently didn’t make any sense, then suddenly after a month it reminded me of Antonello da Messina, the Virgin Annunziata, and I said, “Hey, look, so but in that blue, that fold on the blue fabric, there’s something.” I don’t think I photographed that blue fabric with Antonello da Messina in mind, however, his Virgin, that image, was well present in my unconscious, which retrieved it by making a comparison with the shot of that miserable piece of blue fabric. I don’t want to make comparisons with Antonello da Messina, it would be an insult to his wonderful art, however, that connection with something so important, I don’t know... but it is beautiful.

Look, the question of the texts: they are often texts that have their own poetic characteristic, somehow they evoke a lyrical dimension, it seems to me.

Yes, let’s say that not being descriptive, not being narrative, by necessity they fall there.

But somehow, though, when you take a series of images of your works and put them next to each other, the viewer is somehow invited to create his own narrative.

Ah, of course, a personal narrative yes, although it’s not the most important thing, in fact, it’s something I never think about. But I do understand that it comes up, also because, seeing a series of my works that include texts-not all of them do, for goodness sake, but many do-we are automatically led to interpret them and thus read them as a series of pages; a page is always part of something larger: a book, a text, a notebook, something. That’s when we then look for connections between one page and the next or the previous one, connections that are then, in fact, not there, but at the same time there are: everything can be connected in some way, don’t you think? Also because, what we might call the tonality -- using a musical metaphor -- I decide it and it is that of the way I work and so that one tends a little bit to make, as in the things that you do, that one feels that they are all yours, they are part of a whole. Sometimes I’ve felt myself, when things are done, after deciding which and how to arrange the works on the walls -- which I often and gladly let others, whether they are gallery owners or curators, handle -- here I’ve felt a pseudo story, something like that, completely unexpected.

An atmosphere, a climate?

Yes, there seems to be there too, because then sometimes the texts have the temporal person, the verbal person changing, sometimes they are in the first person, sometimes in the third person, in the first person plural... I mean, it creates a kind of chorality, a multi-voice dialogue. But these are aspects that I’m thinking about right now as we talk about it.

Yes, absolutely, and this is definitely one of the most interesting aspects of interviews with artists, that sometimes even by talking, ideas arise.

And then also being an artist yourself you know that the narrative and interpretation of one’s work is the absolute most difficult thing, and I think there is a part that you have to leave out, omit.

Yes. You don’t have to tell everything!

Also because I don’t know everything about my work either; there is a part I don’t know and I think it is, paradoxically, the most important part of what I do. I happened sometimes to hear, unseen, someone talking about my work and bringing up interesting reasoning and interpretations that I had never dwelt on. So if art really makes you think, it can make you go beyond what it simply and visually represents. It’s like when you start whistling, humming, and then a chorus comes out; some people, first, hum with you, then you let it go and they go on by themselves with unexpected melodies that are often better than the theme that started it.

I also wanted to ask you something: did you ever, for example, use the same image over and over again, maybe changing the text or just changing the toning or the format?

Just the same image no, maybe the same subject, it happened a lot of times. Whether they were then used for some exhibition or publication is not certain, there are subjects that I have photographed often over the years. For example, there is a riding stables that I have photographed frequently. These same trees that I was talking to you about have already been photographed on the opposite side, I think about ten years ago. Explaining why is difficult for me, but it happens. Also that piece of cloth I was telling you about, I’ve already photographed it several times in a church in Liguria, where I go and the priest now looks at me badly because I go there and photograph the innermost corners of the nave where there is nothing, practically.

I would say that there are propitious situations to trigger dynamics, but they are not fully explainable, they remain mysterious.

Mysterious both in terms of thoughts and in terms of creativity, art, therefore its creation. When I read the narratives of the medicine liars or listen to the artists themselves who explain in full detail what they have done, the planning behind their works, what they wanted and did not want to say-and this happens a lot in the new generation, I don’t know if it has happened to you-they know absolutely everything they do and why they do it. I am not admired; in fact, I am annoyed. It’s as if there’s a need to go into a thousand explanations, I also see that there’s a lot of planning right at the base, “You did this, I did that.” Now then it is very fashionable to work with certain areas, certain topics ranging from social to ecological to gender-related; therefore, there are works that are treatises, but they have lost all that is the magical and mysterious aspect of art. Above all, they are limited by history, by the chronicle that gives them a reason to exist and justifies them, even in their qualitative mediocrity. You can often be engaged, you can be political but you have to be bigger than the easy contingency; I am reminded of what Giulio Paolini said (that the link between art and society is obscene), I think it is art that has to influence, even if it is very difficult, society but remaining itself and not the other way around. It is fundamentally a question of culture at all levels, which is lacking and even more lacking in many (not all, let’s be clear, but still too many) institutions and in their top management ... I’ll be silent now.

Of course. It does not have to run after society and social problems.

It must maintain a distance and, if anything, intervene as a trigger for thought, reasoning. His intervention must be intrinsic method....

Yes, exactly, otherwise you end up in all other territories, which have nothing to do with art.

Some time ago I was talking to a gallery owner, a very wise person, about these very issues, and I was asking her, “But look, what should we do? What can an artist do?” and she said, “He has to continue being an artist, he has to do his own thing.” And this “do his own thing” and after that there is someone to observe them, someone to reflect on them, even critically if it happens. And so we connect back to the talk earlier. From there, then, something good for society can arise, but only because you are making, creating motives, causes of thoughts, reflections. Art must be its own thing. It must not borrow themes from current events, even though it is part of them. Because, if I work on topicality as a pure pretext, therefore far from real engagement -- which many people do now -- historically I am finished, because in six months or six days the topicality will already be another. And so, my work, my ’pretend engagement,’ will be totally incomprehensible, empty. Instead, Antonello da Messina’s Annunziata, it keeps on telling forever, it will always have that book in front of it, and I who am watching don’t know what it is reading or why it is looking at me. That’s where the work needs to be done. Yes, that is where there is something that, by remaining contemporary, makes us transcend from the heavy mud of everyday time. We just have to be, to be true, we owe it to ourselves

The author of this article: Gabriele Landi

Gabriele Landi (Schaerbeek, Belgio, 1971), è un artista che lavora da tempo su una raffinata ricerca che indaga le forme dell'astrazione geometrica, sempre però con richiami alla realtà che lo circonda. Si occupa inoltre di didattica dell'arte moderna e contemporanea. Ha creato un format, Parola d'Artista, attraverso il quale approfondisce, con interviste e focus, il lavoro di suoi colleghi artisti e di critici. Diplomato all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Milano, vive e lavora in provincia di La Spezia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.