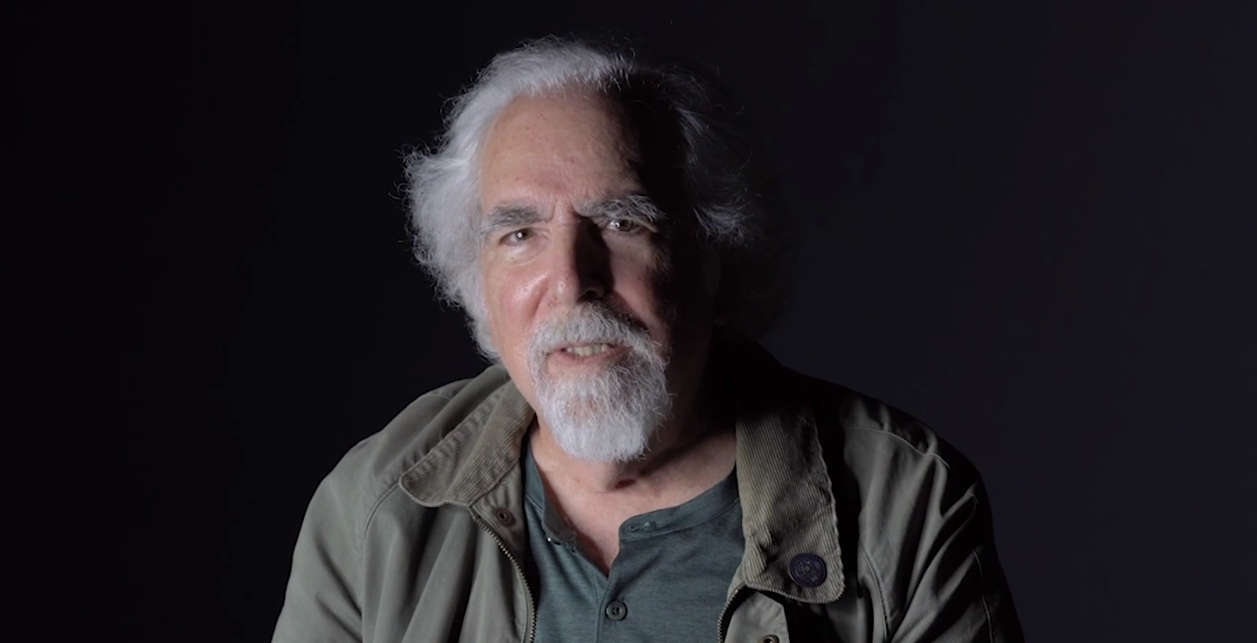

Until Dec. 6, 2023, Peter Campus (New York, 1937), one of the fathers of video art and among the most significant exponents of this expressive form ever, is the protagonist of the solo exhibition Myoptiks held at the Carlocinque Gallery in Milan (all information here). His work has had a strong impact on artists of later generations working with video, and his works are held in several major museums, from MoMA in New York to the Guggenheim, from the Tate Modern in London to the Reina Sofía in Madrid, from the Centre Pompidou to the Whitney Museum. At the Myoptiks exhibition he is exhibiting some of his recent works, which are characterized by a very strong pictorial imprint. We caught up with him in Milan for an interview, conducted by Federico Giannini.

FG. At Carlocinque Gallery, you are presenting some of your most recent works. Can you tell us about them?

PC. I don’t really like to talk about my work because I think the work itself has to be its own explanation, and because I think people can go as far as they can on their own: if they look deeply they will have deep thoughts, if they look superficially they will see it shallowly. I know that nowadays in museums it is typical to have a huge amount of text about the work before you even go to see the exhibition, and so there is a tendency to want to know, from a certain point of view, before you even see the works. That’s also why I try not to talk a lot about my work and simply trust that people will come to their own conclusions. I know from experience, when I worked at the Metropolitan Museum, that people first approach the caption, and then try to find out what the work is about. Instead, I think confusion is a good thing. And I think not knowing is good. Just as I think trying to find out what the work is about is good.

On one thing, however, we can be quite sure: in these works of His you see a lot of nature, you see a lot of landscape. After all, at different stages of your career, the relationship with nature and landscape for you has been fundamental. How is nature a source of inspiration for you?

Everything for me is like a little story. I worked with people for a long time making portraits (and also self-portraits) and observing the human psyche... and eventually I got tired of it all. So I started looking outward instead of inward. And that brought me into nature, I felt in nature. I felt perfectly at home. I feel I have a hard time even explaining it, but I felt really happy once I got into the landscape. Often in the beginning I would walk through the mountains simply because I was there and it was important for me to be there. And now, whenever I work, I would always like to go to a place where I feel comfortable. All these images are like close-ups, because I have to feel the whole environment around me to feel comfortable, so that’s why there is so much nature, that’s why I always have to be surrounded by nature.

This is a very different work from the one that formed the beginning of His path, which started with famous works such as Dynamic Field Series(1971), Double Vision (1971) and Three Transitions (1973) in which He explored themes such as self-image perception, bodily identity, the real and the virtual anticipating many issues that are still discussed at length today. What do you think today about those works, which are now half a century old, looking at them at the distance of fifty years?

I have to live in my presence. I know that fifty years have passed since Three Transisions, and for me it is simply a work from fifty years ago. I am still alive and still working; Bob Dylan says he is an artist and he doesn’t look back. I feel the same thing is true for me. Therefore, I have to be here in the present now and look forward. I cannot look backward. I know other artists do, I don’t: I take no pleasure in looking backward.

You are universally known as one of the pioneers of video art. In an interview you gave a few years ago for the magazine of the National Academy of Design, you stated that even though video art is more than fifty years old, it is still “too new.” Why do you think the public still struggles to understand video art?

Tough question! Perhaps it is because seeing video art has yet to become customary for people, it has to become something ordinary. The public should be able to distinguish between what is on television, what they see on their phones, what is on their iPads, and what is art. Even though art uses exactly the same tools. And he should be able to distinguish between video that is used as an art form and video that is not used as an art form. For me it is important to feel that people understand this distinction. In photography, for example, I think things are moving much faster now, but it took at least fifty years before the potential of the medium was discovered. And I think that has to happen with video, just understanding the basic tools that video presents.

Often, at exhibitions, even major ones, it is not uncommon to see videos with an almost documentary or cinematic slant presented as works of video art. Indeed, the landscape today is extremely diverse, since the language of moving images is now the dominant one. In your opinion, how can one recognize a good work of video art?

I think I am the wrong person to ask this question because I have a very specific point of view and my point of view is that I consider what I am doing from the point of view of what I am doing, and what I am doing is very specific and I feel that it is extremely influenced by photography and the stillness of the camera. So it’s hard to say. I’ve worked in documentary filmmaking so I know that my work is not documentary. I’ve worked in film so I know my work is not film. There is definitely a distinction between one art form and another. We could say that in video art the artist works alone, but I know for example that Bill Viola does not work alone. I know that the Wilson sisters don’t work alone. I know that many other artists don’t work alone anymore. So that is not even the criterion. Maybe more simply, the criterion is that if people say it’s a video it’s art then it’s art, if they say it’s a documentary then it’s a documentary. And in some cases it is difficult to see the distinction between the two. In my case, however, this is not true, in the sense that there is no confusion between what I do in a documentary or in a photograph or in a film...

Some of your more recent work, made between the 1990s and the 2000s, up to the works you are exhibiting here at the Myoptiks exhibition, have employed particular techniques such as pixelization and multi-layering that have led many critics to liken your work to that of a painter (and I believe so too). In your opinion, what does a video artist have in common with artists who instead work with traditional techniques such as, for example, painting?

When we talk about sculpture, we are not just talking about someone like Michelangelo sitting down and carving stone. We cannot, for example, say that it is not sculpture, for example, the work of someone who takes a mass of molten steel and puts it on the ground and says that is a sculpture. So lately even I have been wondering if I am not a painter. After all, I work with color. I work with light. I work -- I mean, I feel I’m part of the painting tradition, but I know very well that I don’t want to work with paint. I grew up with television, I grew up with video, I grew up working with this medium and I am very seriously committed to video as a medium, but I also think of myself in the tradition of painting, as you say. However, I think the question is also about why I am not a painter if I believe in the tradition of painting. So, first of all, I like the temporal dimension in my work. I like the fact that it’s moving. That it is breathing. In Duchamp’s Étant donnés, for example, there are elements that contain movement, there is of course a sculpture that moves, but the movement in time, that is, the dimension of time rather than the dimension of space, seems to me more an extension of painting. So I feel, in many ways, that I’m simply making some progress in painting, and I mean now, not fifty years ago. There has always been a strong painterly quality to my work-I started painting when I was 13, and I painted until I was 23. Going to museums has also had a great influence on my work (I do it a little less now because I live outside New York, but it remains extremely important to me). I am probably more interested in painting than in any other historical art form. And I see myself simply as continuing the tradition of painting.

You mentioned Duchamp, you said that visiting museums was crucial to your work, and that you are interested in ancient painting. What artists, then, have inspired you?

I would say. almost all of them. Maybe Corot, maybe others, I don’t really know. I have a passion for all painting. When I looked at paintings from the Middle Ages or the 14th century I was struck by that idea of line, color, depth... I think for example of Assisi, the Basilica of St. Francis, certain paintings I saw in Umbria... it’s something simply extraordinary ... the spiritual elements of these works have always had a deep meaning for me. Then in Florence there is the convent of San Marco with the works of Beato Angelico, an enormous amount of Beato Angelico, there is a Beato Angelico in each of the monks’ cells... and when I visited it I thought “oh my God but is it possible to imagine living with a Beato Angelico in your cell?” With your bed and your table and your Beato Angelico. I mean, there is so much to look at in this world that . you just have to look. Anyway, all painting interests me. Maybe more ancient and spiritual painting than contemporary painting, although then there is Mark Rothko whose works seem very spiritual to me. In short we could go on answering this question.... for another hour or two!

Today we are immersed in a reality where everyone is expressing themselves with videos. Not only, every day, we are inundated with moving images through television, the Internet, and social networks, but thanks to the evolution of technologies we ourselves have become producers: creating a video, editing, adding effects and music, thanks to new programs on computers and smartphones, has become super easy and we are even more inundated with videos. In your opinion, what are the advantages and, conversely, the risks of this situation?

Meanwhile, art is art: when I started making art and the public started to say “video art,” I used to answer “no, no video art... art!” I lost, though, and it became “video-art.” Anyway, even in the little town where I live, everyone who paints shows their little paintings here and there, everywhere, but what does it matter? Do other painters make El Greco inferior to himself? No artist makes another artist different from himself. I mean one thing is art, and another thing is not art, it is entertainment. So in my opinion this situation is neither a danger nor an interference, except for the fact that if you are interested in art you can look and see what art is, and if you are not interested in art you can look at everything else. I don’t know the names of social media, but I don’t see them as a danger, not at all, although I could be wrong, I also recognize the position of those who do say they are a danger. If there is a danger, if anything, for me it is more in terms of education, which has to do with understanding the dimension of art, understanding the artists’ intention. When we look at Chartres Cathedral we see all these works sculpted by unknown people, but they are still art. I think we have to judge art starting from the work of art and not from the name of the person who made it. I think this. From my point of view the question is to understand what the art is, not to understand what the medium is.

Finally, since we are in Milan, since we talked about Beato Angelico ... I would like to conclude by asking you what is your relationship with Italy.

It is very good. I am probably happier here than in other places. Let’s say that in Italy there is a sense of art that is better than elsewhere, a sense of clothing, a sense of architecture, a sense of landscape ... all better than elsewhere. Today I walked past a field of sunflowers and felt that -- this is God’s work. Here I am in the presence of art. It is a field of sunflowers. Think for example of architecture, in Italy when you build there are precise directions based on the place, in my opinion it is an extraordinary thought. Even in Greece then everything is beautiful and exceptional, yes, but it’s not for me (so I hope this interview doesn’t make it to Greece!). I feel comfortable with the Italian culture and sensibility, I am really at ease here. Even more than where I live, in a small town a hundred miles from New York, and when I’m there I miss the Italian cafes, I miss the idea of sitting somewhere and having a couple of chocolates... here in Italy life is really extraordinary.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.