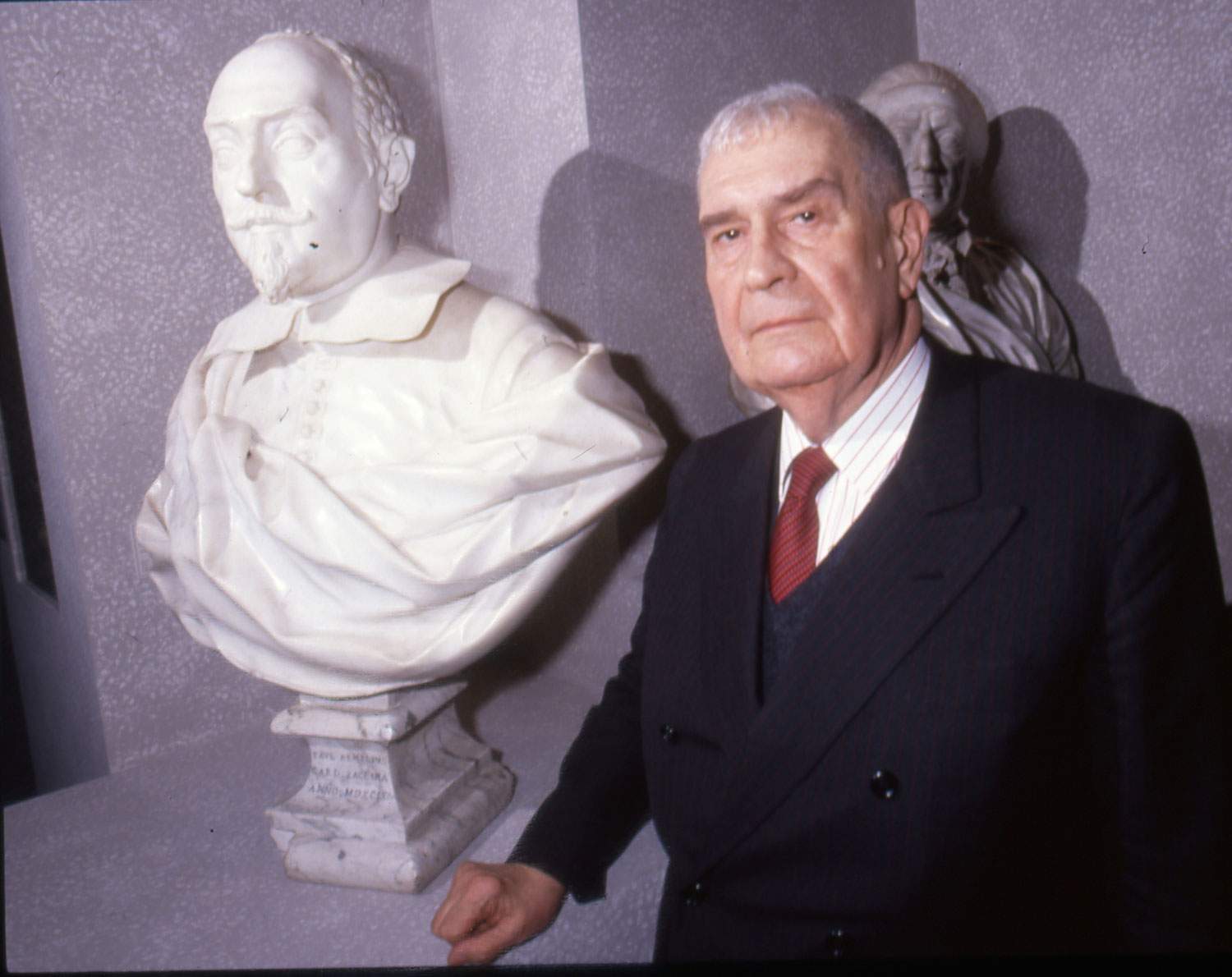

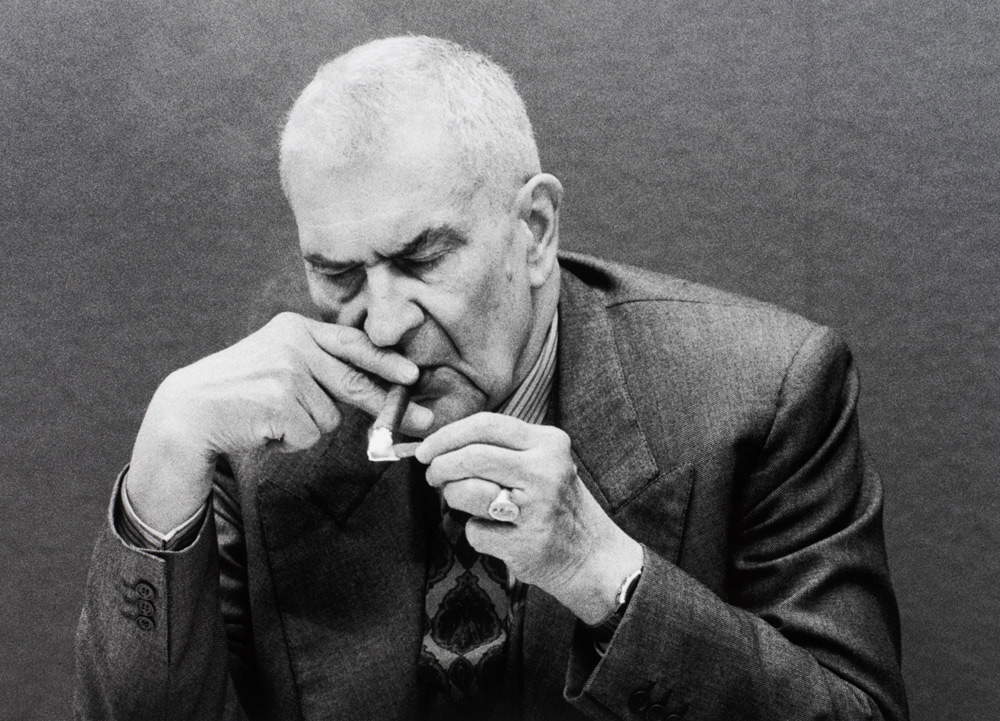

August 1996. Federico Zeri’s house in the countryside of Mentana, near Rome, appears as an extraordinary fortress within which the scholar enclosed himself to fight a personal war against the gloom of the times. A most faithful mirror of his omnivorous intellectual curiosity, in the many rooms stand crammed together with absolute naturalness paintings, sculptures, fragments of ancient marbles, bronzes, mosaics, carpets and thousands of books that from the overflowing shelves descend to the ground in gigantic stacks, themselves covered with layers and layers of photographs of all kinds. The long-standing friendship means that we are allowed - with me is mutual friend Marie Massimo Lancellotti - into his bedroom, where he is immobilized by a minor domestic accident. The room is upstairs and looks like the rest of the house, filled with books. The difference is that they are almost never volumes of art history, but mostly of literature: novels disparate from one another by era and author, and short stories: even detective stories. Next to these, stand rows and rows of film cassettes and towering towers of compact discs. Zeri’s nights are indeed not too much accompanied by Pietro Cavallini, Giovan Angelo d’Antonio or Giuseppe Valeriano; but much more by Ernst Lubitsch, King Vidor and Visconti, by Mozart and Mahler, by Stendhal, Thomas Mann and George Simenon.

BZ. Professor Zeri, where is art history going today?

FZ. In Italy, it has remained at philology. That is, it has not gone beyond that first stage, which is moreover indispensable, of the classification of works, which then corresponds to the ordering of literary material, the reconstitution of critical texts, etc. In other countries, especially under the influence of the German and then Anglo-Saxon schools of the first half of this century, there have instead been other approaches to art history: studies of iconography and iconology, studies of the relations between art and society and between art and economics. All methodological approaches that have had a very stunted and almost always questionable life here.

Not to mention the inattention to the problems of techniques of execution, confined to fanciful amateurish hypotheses about the commonplaces of patinas and secret recipes; and never instead focused on the relationship between artistic production, technical treatises and the organization of work in the workshops and workshops. Why, in your opinion, has everything remained in this backward condition with us?

For a judgment on the history of Italian art one must go back to its modern origins. These days a very interesting book about an eminent scholar of Italian art history, Adolfo Venturi, edited by a very good young art historian, Giacomo Agosti, has come out. A man of great open-mindedness, Venturi made an extraordinary debut. Fundamental still remain his youthful research on 15th-century Emilian art: from archival papers to the recovery of figurative texts. But Venturi’s studies later flowed into his monumental Storia dell’Arte Italiana, which is a mere philological systematization. Never does a discussion of the relationship between artistic production and contemporary society appear there: for example, on the reasons that urged Renaissance tyrants to illustrate their names with great monuments and great paintings, or on the relationship of Mannerism to the crisis of religious thought in the first half of the 1500s.

And after that?

Venturi’s legacy was then perfected by some of his important pupils. First Peter Toesca, to whom we owe those great monuments to art history studies that are The Middle Ages and The Fourteenth Century. Even those, however, remain a systematization of materials where it is very difficult to find an opening toward views and approaches different from those of the beginning. Other great students of Venturi were Giuseppe Fiocco and Roberto Longhi. Fiocco had a prodigious philological knowledge of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century painting, especially in northern Italy. While Longhi was certainly an extraordinary figure in the field of scholarship; but that is not why he succeeded in being a historian, that is, an art historian in the full sense. In fact, he remained a philologist with exceptional intuitive qualities, to which he added the ability to know how to present his findings in a post-D’Annunzio literary language, which up to a certain point was of great beauty. Though not like that of the model. However lofty, Longhi’s language never reached the level of, for example, the pages devoted by D’Annunzio to Venetian painting in Il fuoco.

In any case, Fiocco and Longhi later had pupils of their own.

With one difference: that Fiocco was a regular university professor. Longhi was not. He had such a strong personality that he conditioned his pupils to such an extent that then those pupils no longer dared to contradict him; and throughout their lives they continued -- and still continue -- to write essays and books based on the formula “as well as Longhi saw” and willing to defend his errors anyway and everywhere. Let me give you an example. In the 1940s Longhi gave a lecture in which he reconstructed in hypothesis the activity of what all sources said was Giotto’s greatest pupil, but whose documented works have all been lost: Stephen the Florentine. The reconstruction was based on the possible similarities between the characteristic “dolcissimo e tanto unito” painting described by Vasari in the life of Stefano, and the formal qualities of a very homogeneous group of wonderfully beautiful Giotto paintings, almost all located in Assisi. After that, for some thirty years there was no art historian who, speaking of fourteenth-century painting, did not take that hypothesis for true and find a way to put “Longhi’s Stefano” into his reasoning. At a certain point, however, an archival document came to light showing that all the paintings attributed by Longhi to Stefano were in fact the work of a very high and semi-unknown painter from Assisi, mentioned in passing by Vasari in the life of Giotto: Puccio Capanna. Since that time a black blanket of silence has fallen over this matter; and practically no one has ever again mentioned either Stefano or, poor man, that very great painter who nevertheless remains Puccio Capanna.

I know the matter well, because I myself restored the work that made it possible to restore Puccio Capanna’s authorship of that group of stupendous paintings: the fragmentary fresco of one of Assisi’s city gates, now preserved in that city’s municipal picture gallery. What a notarial document attests was allotted on November 24, 1341 precisely to Puccio Capanna and his partner Cecce di Saraceno. But beyond that, what did the figure of Roberto Longhi entail for the history of Italian art?

It has entailed that, especially from his university lectures in the 1930s and 1940s in Bologna, some important art historians have emerged, such as Alberto Graziani, Francesco Arcangeli and Carlo Volpe. But that a kind of closed university circle of his students was then created, which turned the teaching of a very high figure, which Longhi’s was anyway, into “longhism”: that is, into the tendency to classify everything into “great genius, minor genius, follower, satellite, friend, pupil.” But those classifications with art history have very little to do with it. In fact, they serve only to foster the formation of hierarchies of values in function of that real Italian scourge that is the commercialization of art. That which, beginning with Adolfo Venturi, has had as its fallout the epidemic of expertises, ranging from the page written in the form of a letter, to the magazine article, and even to the actual monograph. All texts aimed at accompanying with resounding attributions works that are almost always mediocre, or enhancing certain artists at the expense of others for pure reasons of monetary gain.

Which monetary gain, however, has ended up being an unintended gauge of art historians’ quality. In the sense that antiquarians stake all their professional credibility on selling artifacts for what they really are, thus for their true value and never for less. So that the best art historian inevitably becomes the one who gets attributions wrong the least. And it is for this reason that medieval art, whose artifacts are in practice almost absent from the market, is the one where huge critical abuses are still being committed without anyone basically saying anything. You try bending to your own use, falsifying them, the measurements of a carved slab to prove to an antiquarian that that object came from inside Modena Cathedral. When the antiquarian realized the scam, and that he had risked deceiving a customer by telling him lies, at the very least that slab to the waffling art historian would be broken over his head. While the same fact, when it really happened a few years ago, left the world of medieval art history studies completely indifferent. In any case, can you give me examples of “texts aimed at accompanying with lofty attributions works that are almost always mediocre, or at enhancing certain artists in spite of others for pure reasons of monetary gain.”

The endless monographs and the deluge of exhibitions, catalogs and articles that have come out in recent years on Caravaggio: each with within it the presentation of the unpublished work, which then almost always is not by Caravaggio. While there are entire schools that are very little studied and published, because the shouty name is missing. Such as Ligurian painting of the 15th century, which only recently, thanks to the fine volume by Giuliana Algeri and Anna De Floriani, has become known with works and names. Or, to take another example, the studies on Romagna painting of the 15th century, which have basically stopped sixty years ago. Not to mention art in the extreme southern tip of ltaly, still effectively unknown. As if painting and sculpture were only that of the elites of the great courts of Rome or Florence, and any other art form deemed peripheral or minor could be removed from study. And this, not only in deference to a proven tradition of scholarship, but also in purely mercantile function.

However, art dealers have always existed.

Let me explain further. I see nothing wrong with the art trade. It has always been there, also because there have always been private collectors. What is serious is that only a slice of art production is privileged solely because it is the only one that can be marketed. And it is scandalous that this is done by scholars who carry out their research primarily for the purpose of promoting such a group of paintings or drawings that are on the market. As Adolfo Venturi did first, followed then at a gallop by Longhi, Fiocco and so many others. Not to mention the absolutely incredible case of a superintendent with a very solid reputation as a menagramo going around Rome today signing expertises for antiquarians. Frankly, I don’t understand why, although I have reported the matter several times to various ministers, none of them has taken that guy by the ear, perhaps first arming himself with a powerful amulet, and not fired him on the spot, since his job as a state official is to control the fairness of the antiquarian market: not to favor it.

However, I do not think antiquarians should be blamed for the moral nonchalance of many art historians.

In fact, I do not blame them. I am well aware that, in many cases, antiquarians are owed the salvation of very important works of art and monuments, as well as the promotion of valuable art historical studies. One thinks of figures such as those of Bardini and Contini Bonacossi in Florence or that of Volpi in Città di Castello.

Let’s change the subject and talk about the protection of artistic heritage. What experience have you gained from the role you have been playing for some years now as vice-president of the National Council of Cultural Heritage: which is then like saying vice-minister, since the president is, ex officio, precisely the minister?

Not very bright. Let me try to give you a list of the problems that seemed to me the most serious. First, the National Council is too large, so you can never make decisions on real problems. When a discussion starts, always the parish priest of Roccacannuccia or the alderman of the municipality of Vattelapesca rises up, who on the basis of completely amateurish municipal considerations places absurd vetoes, preventing those who want to work from doing so. This makes the National Council instead of being, as it should be, the point of reference for the elaboration of a coherent protection strategy for the country, become the mediocre stage on which unknown characters perform, who reap their moment of celebrity by holding useless as well as interminable speeches on issues of little or no substance. Second, it seems to me that there has so far been a lack of a minister who, in addition to a thorough knowledge of the often widely differing problems of Italy’s 20 regions, also has the pulse and courage to address those problems and solve them. Nor do I seem to see any political forces around who have the will and strength to give up the logic of compromises along the lines of “volemose bene” and “tengo famiglia” with which ltaly has been governed so far. Third, it is unacceptable that in a country like ltaly, which has an immense artistic and cultural heritage, officials are paid pittance salaries. It would be enough to subtract 0.1 percent of the budget from Public Works to fix this situation. But no Minister or Director General of Cultural Heritage has ever tried to do so. Fourth: there remain in the Ministry heavy legacies of characters, whose names I do not want to mention, who held prominent positions within it in times past. Fifth, there is the very serious problem of the lack of a catalog of the artistic heritage. I understand that the work of scientific classification of a heritage consisting of many tens, perhaps hundreds, of millions of works of art, such as ours, may be behind schedule. However, it is not admissible that a photographic inventory of it has not at least been carried out in the meantime: the only one that can help us against the myriad of art thefts that occur every day in Italy. Even less admissible, then, is the fact that many museums are deprived of a systematic catalog: that is, places that are perfectly circumscribed and often holders of small heritages. While a real mockery is that there are repeatedly repeated catalogues without ever having been published: for example, that of the province of Rome. Sixth, the ridiculous position of the Central Inspectors, kept in a Ministry office where no one looks for them and where no one makes them do anything, needs to be rediscussed. An office that more resembles an elephant cemetery than the place where the Ministry’s top experts are gathered, as the pompous title of Central Inspector would lead one to think. Seventh, there remains the problem of the irrationality with which the very large number of state-owned properties are managed. In Rome, very important buildings are in the hands of entities that could be evicted without shedding too many tears. While in the same city, one of the world’s greatest museums of ancient art, that of the Baths, is being split into three separate locations, the Museum of the Middle and Far East has to pay rent at Palazzo Brancaccio, and the National Gallery of Ancient Art at Palazzo Barberini fails to be the great museum it could be just because its location is occupied by the Army Officers’ Club. A crazy thing.

Do we end the problems here?

No. I would add to it that another monster created by this system are the more or less international relief chains dedicated only to a few large centers, such as Venice, Florence and even Rome. The fuss that these chains of San Antonio raise actually obscures the agony of the very precious connective tissue outside the big cities: that is, that set of small and even infamous localities where even distinguished works of art are allowed to die. I am familiar, for example, with the issue of Abruzzo, where real havoc has been wreaked over the past 50 years. There are endless monuments ruined not already by time, nor by earthquakes or war, but by wrong restorations, or started and never finished, carried out by the Cultural Heritage Administration itself. I do not feel like giving you the full list, but there are incredible cases of huge sums spent by the state to devastate public monuments, that is, practically its own: see the church of Santa Maria di Collemaggio in L’Aquila, or that of San Francesco in Tagliacozzo. I will be told: the church of San Francesco in Tagliacozzo is a second-class monument. Agreed. But the altars they demolished reflected the whole history of the town and the main families who had lived there for centuries. Not to mention that those demolitions resulted in making a church filled with history into an absurd medieval hangar all made of neon-lit stone, with the altar paintings stripped of their original frames and hung from iron wires. A series of tragedies, these of new museum and church layouts, caused by the endless number of architects who think they are innovative because they copy illustrations from some book on American rather than German or Finnish design: that’s how they do Finland in Tagliacozzo!

Provincialism or ignorance for these all-same arrangements, which, foolishly destroy centuries-old cultural stratifications of churches and brutally erase the municipal pride of local collections?

Certainly both. But powerfully favored by the complete absence of any form of state supervision and direction. The kind that central inspectors could very well carry out, to return to what I was saying earlier; but which the Ministry does not allow them to do, preferring to keep them moldering away inside offices. Back to Abruzzo. Just these days I would like to write an article with a list of things notified by the State in that region and destroyed in the last fifty years: it would be an interminable list. I would like to do the same for Sicily, where there are places where the superintendencies seem never to have arrived. For example, the mountainous area of the province of Messina, where I myself have seen polychrome wooden sculptures left in the pouring rain in churches without roofs! Shall we then talk about the hundreds of frescoes that without ever having been photographed are falling apart in the many churches now abandoned to themselves in the countryside and, especially, in the Apennines?

A solvable problem how?

I have already told you: first of all, superintendence officials must be paid much more. Only in this way can their scientific preparation, which is often modest and in some cases non-existent, be demanded to be checked over time; and only in this way can they be given precise and detailed assignments, demanding strict adherence to them in time and manner, failing which they can then proceed to the necessary dismissal. Were it up to me, for example, one of the first things I would do would be to divide the tasks between those who set up exhibitions and those who exercise control over the artistic heritage in the territory. Two completely different professions, of which the former now seems to have completely obliterated the latter. Today, in fact, Superintendence personnel are increasingly being engaged full-time in making exhibitions that are generally useless, if not shoddy; while almost no one goes to see what happens to monuments, churches, frescoes, canvases, panels, sculptures, goldsmiths, fabrics, wall hangings and whatever else is in the territory.

That is, it is just a matter of creating conditions of efficiency in the work of the Administration.

That’s right. Except that to do so, those who run it from the center should take command responsibility over the men they have at their disposal: that is, publicly recognize that such a superintendent, who shows in the facts that he is an educated and competent person, should be promoted to roles of responsibility; while such another superintendent, who from the height of his incompetence and cultural coarseness thinks that his role is to give fines to everyone and to issue nonsensical prohibitions, should be sent away from the Administration, perhaps occupying him more usefully in traffic policeman duties. But in Italy no one wants to govern, because no one wants to displease the people. Although there have been exceptions: for example, Alberto Ronchey, who faced some problems, or Domenico Fisichella, who in the few months he was in office revolutionized the top management of the Ministry.

The problem mainly addressed by Ronchey was that of the enhancement of the artistic heritage. He did so with his law on museums, No. 4/93, which, however, ran up against the welter of the roughly 170,000 pieces of legislation produced from Unification to the present, which make all Italians guilty until proven innocent. So that, in order to guard against suspicions of favoritism in the awarding of contracts, the law has been flanked by regulations so complicated that they are, as everyone says, very complex to enforce.

Already! Italy’s 170,000 laws, compared to just a few thousand in England and France. This figure would be enough to qualify the country we live in: an ungovernable province where everyone is given the widest freedom to argue about nothing, so much so that trials never last less than 15 or 20 years. So that everyone lives in the most complete uncertainty of their right. But even the so-called Ronchey law on museums, which remains very important, moves from provincial facts. The discovery of merchandising in museums, which is the substance of the law, in fact imitates what has been happening normally for many years, for example, in the United States. Only there, museums have a constitution and programs quite different from ours. Beginning with their eminently educational purpose, recovery of the European cultural tradition, and social representativeness. But since at the entrance to the American museums there is the store where books and gadgets are sold, and concerts or luncheons are often given inside them, the official of our Administration or our politician, who happened to be there for a vacation with his wife and puppets, were impressed and immediately said to themselves, “That’s how to be international!” So, back to the small town, off they went with “Gonzaga-esque” ballets at the Ducal Palace in Mantua, with concerts at the National Gallery in Parma or with fashion shows at the Uffizi and in the Medici Tombs, putting Michelangelo Buonarroti on the same level as the troupe of Armani, Versace, Valentino. And everyone, newspapers, television, the Ministry applauding, because this is how we exploit what you ridiculously continue to call “our oil.” Never mind the safety issues for works of art and spectators: for example, if a fire breaks out: the tragedy of the 34 people burned alive at the Todi antiques exhibition in 1982 evidently taught us nothing. What is really serious is the disheartening spectacle of a nation giving up the historical root of its own extraordinary culture and reducing itself to a petit-bourgeois province especially of Anglo-Saxon countries, if not a Disneyland for art tourism.

But why only two decades ago were such operations impossible?

They were impossible as long as there existed in Italy a small educated elite who counted for something. Whereas today culture and intellectuals no longer interest anyone: look at how the third pages of newspapers are reduced. But much of the indifference to works of art also depends on what I was saying earlier: on the privilege of philology in the field of art historical studies.

In what sense do you say this?

Because Italian-style philology isolates works of art into a set of figures independent of the historical contexts that produced them; and so it ignores what may be the civic engagement urged by the protection of works of art understood as a whole inseparable from the context that produced them. Have you ever examined the journals that have recently come out with editorial boards almost entirely made up of the younger generation of art historians? Take the summaries and you will see that the articles are all, “A ray of sunshine on Taddeo da Poggibonsi”; then, “A new contribution on Taddeo’s friend”; then, “Revisiting an ’Annunziata’ by Bartolino da Montecatini.” The same titles between Pascoli and D’Annunzio from magazines 50-60-70 years ago. And when I asked one of these young people how it is that they, who all say they are on the left of the left, instead of taking a strong, solid, conscious stance of denouncing the ruin that looms over our artistic heritage, they write articles on philology that inevitably end up flowing into those antiquarian economic interests to which they say they are absolutely opposed. Well, when I asked him this question that one replied, “we don’t berate.” It is the usual cowardice of the Italian middle class, its lack of a true civil conscience, less than ever present in the so-called intellectual class. How many university professors were there who did not swear for fascism? 12. How many Italian intellectuals have publicly denounced the atrocities of communism? Maybe not even twelve.

So you don’t save any Italian art historians at all?

Some there are. But they are very few indeed. Their number could be deduced from the letters from superintendents and university professors who denounce in the newspapers the neglect and incompetence that led to very serious events such as, most recently, the collapse of the Cathedral of Noto. You practically never read about it. But then what does not work is the system as a whole. You think about how art history is taught at the university: how many professors do you see in museums with their students? Very few. Let’s even admit that because museums are public, visitors make it impossible for a professor to lecture in them. However, Italy has, unlike all other countries, a wealth of repositories that could magnificently serve as study collections where students can see works of art from life and not in slides or photographs. Remember that it is far more important to examine a single painting in the original than a hundred thousand words ex catedra, among other things often spoken in abstruse language because it is unnecessarily researched and literary. I present a case. In Florence there is a public collection that almost no one knows about, donated in the 1930s to the city. I speak of the Corsi Collection, which consists of many hundreds of paintings including important, remarkable, crusts, copies, and fakes. This collection is housed on the second floor of the Bardini Museum, which is not accessible because of the risk of floor collapse in case of an excessive influx of people. On the ground floor, however, there is a large empty hall, where a selection of these works could be temporarily displayed and lectured on. Based on concrete examples, students could be taught to disentangle the different styles of the authors of those paintings. But above all, they could be made to understand that a masterpiece can be historically less important than a minor work; that a mere devotional crust can represent the religious sentiment of a population much better than an important altarpiece; that a forgery can represent the religious sentiment of aa population; that a forgery can explain far more succinctly than the originals the taste of an era; that a work may have been ruined by natural reasons but also by bad restoration; what a repainting is. It is only in this way that the philologist’s skills are formed and the basis for that knowledge on which to then cross-reference the works with the historical, cultural, social, political, and religious contexts in which or for which they were executed.

And why is this type of lecture not done?

Because the Italian university professor is like Melchizedek or the pope: once appointed “tu es sacerdos in aeternum”! Whereas throughout the civilized world, with very few exceptions, university professors are hired on renewable contracts every 2 or 3 years, on the ballot not only of faculty colleagues but also of students. If this were done in our country, for example, it would immediately end the scandal of professors giving one or two lectures a year, entrusting everything to assistants, deputies, bagholders waiting to be deputies, the journalist “because with the press it always pays to be friends,” to the superintendent “because that’s how he calls me if he makes an exhibition,” to the traffic police chief’s wife “so if I get a ticket he’ll take it away,” and so on. Instead, with that kind of cross-checking, professors would finally be forced to take up their professorship full time: that is, to do the work for which they are paid by the state with public money. Only in Italy, university professors are a taboo. An untouchable sect that has led to the formation of politically and commercially motivated cliques and the bins of rigged competitions. Who tells them anything anyway? Books have even been published describing these rigged competitions, naming and shaming benefactors and beneficiaries. Have they ever hit one? Never! They all stay nice and cozy in their chairs doing their maneuvers in the name of the Italian people! And if you really insist on complaints, you are answered as believers do when they talk about dishonest priests, “you know, the flesh is weak.” You try giving justifications of this kind in Anglo-Saxon countries, where just the shadow of a suspicion in moral or administrative behavior leads to immediate dismissal. You see what would have happened in the United States if the newspapers had carried the news that a university professor was suspected of organizing a fake robbery in order to make disappear the evidence of a scam of fake paintings sold with his endorsement to a naïve dealer, as happened in and around Rome in Italy! You see what would have happened, again in the United States, if the newspapers had again reported on a university professor who had received a million dollars from the state to organize exhibitions that were never held or to open to the public a museum that then remained hermetically closed, as happened in Italy to a professor who received billions of liras from the state for that mysterious university museum at Csac and for phantom exhibitions on Parmigianino and Correggio! See for yourself if these two characters-in the United States, but also in any other country other than Italy, including the Third World-instead of remaining undisturbed in the chair as they are, would not have been sent home while waiting for a special judicial inquiry by the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Court of Auditors to publicly clarify the issues of robberies, false or true, and billions of the State gone to nothing!

To confirm the unbelievable situation you describe, it can be added that the same chairperson of the phantom exhibitions was the director of the “mysterious museum” for some 20 years; after which the position passed to his wife. A dynastic succession that comments abundantly on itself; and yet it fell into complete general indifference. In any case, do you not think that one of the main reasons for the neglect of the artistic heritage also stems from the absence of a real interest of civil society in its defense? An interest that until not too many years ago was in the facts - just think of the anathema that hung over sacrilegious thefts in churches, which are now the order of the day -, but which in the present can only be achieved by a school policy of education in the knowledge and respect of our artistic heritage. A goal that should be achieved above all by working on elementary school children. While today art history is taught for very few hours a week only in classical, scientific and art high schools, with, moreover, the cyclical ministerial proposal to abolish it altogether. Nor can this indifference of the Ministry of Education be replaced by the voluntary and often meritorious educational initiatives of some superintendencies.

He is absolutely right. Incidentally, doing so would also have the important effect of removing from the present condition of underemployment, if not direct unemployment, almost all young art history graduates. One should establish in all the museums of our cities one or two rooms displaying not originals, but reproductions; and on those teach children to look at paintings, as is done, for example, at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Perhaps it would also be the only way to avoid the acts of vandalism, such as writing, holes and scratches, that the bored and indifferent herds of students taken on school trips to Assisi, rather than to Rome or Florence, perform on paintings and statues with now constant frequency.

Indeed, in the early 1960s Ennio Flaiano had prophetically written -- and I quote from memory -- that “the Colossus of Rhodes did not fall because of an earthquake, but because it was undermined at the base by the signatures of tourists.” Don’t you think, however, that if we really began in Italy to teach art history to children, we should above all make them know and love the historical and artistic testimonies of the territory in which they live? Only in this way can one hope for a reaction of civil indignation when a truck should arrive in front of the church in their town or village, with thieves charging at the altar cloths or marble balustrades in the presbytery area. While I myself have witnessed superintendents’ educational exercises during which children were being talked to about subjects completely out of their reach, such as the iconological significance of still life or the historical roots of Impressionism.

With kids going to sleep or making a racket and still understanding nothing about those things, because nothing they can understand. You see, the problem is always the same: the petit-bourgeois culture of that Italian middle class that I detest even for episodes like this. Iconology is a very serious and important method of investigation if people of boundless culture and erudition, as Aby Warburg or Erwin Panofsky were, apply it. It becomes, on the other hand, a laughing matter if those talking about it are a series of people venting their frustration as failed art historians by repeating to poor children little lectures they learned years earlier in college. That Italian-style “do-it-yourself” iconology that resembles the dietrology of a certain journalism of ours: here’s the smartass who explains “what really lies behind a fact”; there’s the smartass who discovers “the real message” hidden inside the painted image. Regarding Impressionism, on the other hand, the success that makes it an evergreen workhorse is due to its more than widespread diffusion in reproduction as a petty-bourgeois decoration of the apartments of the usual Italian middle class: along the same lines, to be clear, as the cuckoo clock. Just think that in Milan, a wonderful exhibition on Alessandro Magnasco and another on the Impressionists in the Russian Museums were recently opened at about the same time and in the same venue of the Royal Palace. For the Impressionists there were very long lines of people waiting; while at the Magnasco exhibition no lines and four cats inside. For what reason? Because the people in the long lines can always reduce an Impressionist landscape to the comment, “Look at Righetto! it looks just like er Soratte as seen from aunt Elide’s house”; while very hardly can they have an emotional adherence to the complexity of thought and existential drama of Magnasco’s painting.

Perhaps, however, Italians follow Impressionist exhibitions with such interest because it becomes the only way to see paintings of that school, since there are none in our museums.

Actually, it should be said that in our museums there are only works of art that the state more or less accidentally found itself holding at the time of the Unification of Italy. And thank goodness that this was by far the most important and conspicuous artistic heritage in the world, and therefore able to live largely off its income as it was! Why, after that, no King, Duce, President of the Republic, Minister has ever been touched by the idea of buying a few important pieces on the market to supplement according to a rational design what we already possessed of antiquity. Or, when it was done, we made the whole world laugh. For all of them, the grotesque affair of the “Madonna of the Palm” is enough. A ludicrous crust that the then Superior Council of Antiquities and Fine Arts mistook for a work by Raphael and therefore had it bought by the state, allocating it to the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino: the latter, Raphael’s hometown, where, however, no work by this supreme artist remains. Nor was there any thought, with the sole exception of the small collection established at the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome, of having to collect evidence of what contemporary art was creating in the field of art for Europe or in the United States and the rest of the world. Italy had within its borders formidable paintings by Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, but it let them all out. All the Cézanne from Egisto Fabbri’s collection, for example, ended up in the American Embassy in Paris: and they were absolute masterpieces. Then the beautiful version of Eduard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe that was in Milan: gone, too.

How could this happen when in Italy we tend to notify everything: the possible and even the impossible?

The explanation is that at the beginning of this century there was an anti-French campaign in Italy: so those artists did not take them seriously. Just think that when the great Cézanne exhibition was held in Venice in 1920, one of the top representatives of the Italian intelligentsia at the time, Emilio Cecchi, devoted his attention to Ignacio Zuloaga and not to the great French painter: as it was said at the time, “he liked the Impressionists better!” An attitude, Cecchi’s, moreover, not unlike Ugo Ojetti’s proud pernacularities always to Impressionist painting: as the militant Fascist critic that he was, he granitically affirmed that art “by us, must be Italian.” But the most incredible thing about this situation is that, while on the one hand our critics demolished French painting or ignored it, on the other hand they tried to re-evaluate nineteenth-century Italian painting, without, however, understanding it; and thus handing us unclean crusts as if they were great works. Recently I have seen some paintings by completely unknown postmacchiaioli that are absolute masterpieces. But extraordinary painters are also certain verists, who have works often of such high quality that they stand on a par with the great Russian naturalists of the time: for example, the landscapes of Guglielmo Ciardi. How is it then that of Giovanni Fattori we were only shown the scribbles on the lids of cigar boxes, while his great paintings, those indeed truly marvelous and the result of much more care and effort on the part of the artist, seemed almost not to exist? What about nineteenth-century painting in Genoa, Naples or Palermo?

It is somewhat the same logic by which people preferred Antonio Canova’s sketches to his wonderful statues, calling the latter “coldly academic.” Yet another demonstration, not only of the total inability to promote 19th-century Italian art in international esteem, but also of critical blindness, since what Canova dismissed as his works were precisely the great sculptures and certainly not their sketches.

I would say that in contrast to other European countries, I ltaly has directly ignored its own nineteenth century. An attitude somewhere between suicide and provincialism, which is the exact opposite, for example, of what happened in France for the Impressionists, supported with an unprecedented publicity battage, in which the state also participated by building museums dedicated only to that type of painting. Another confirmation of the provincialism of our critics is the complete disinterest, until recently, in English painting of that same period. Almost as if giants of painting such as William Turner, Frédérick Lord Leighton, Lawrence Alma Tadema had never existed. Only very few in Italy at the end of the 19th century knew and appreciated that painting: one was Gabriele D’Annunzio. Not to mention another cultural fact of enormous importance for anyone who really does the job of an art critic. The perception of nature in photography and film does not come out of the Impressionists, but precisely out of English painting. There are compositional solutions, in Alma Tadema for example, that are equally found in Hollywood cinema of the 1930s and 1940s. The same for literature: many themes in American cinema up to the 1950s come from nineteenth-century English literature, certainly not from The Betrothed.

Our twentieth century was also then quite left to its own devices.

This is demonstrated by the scandal of the failure to protect its things, particularly buildings. The crazy appendage made to Giovanni Michelucci’s Florence Station, which disfigured one of the few major works of modern Italian architecture. Or the construction of the Olympic Stadium in Rome, which nullified the wonderful relationship between buildings and landscape at the Foro Italico. Finally, also in Rome, the very serious affair of Piazza Augusto Imperatore. Beautiful or ugly, it has been there for sixty years now and is still part of a moment in the city’s history. But the City Council wants to undo it to place an auditorium there. It is the usual Italian middle class that thinks it can redeem its petty-bourgeois provincialism by imitating some foreigner. In this case, perhaps, the grand constructions promoted by French presidents, such as Pompidou’s Beaubourg or Mitterand’s Défense. After that, the mayor of Rome will think he has made international a city where you cannot walk on sidewalks because of dog poop or where entire historic buildings are scarred and ravaged by vandals by day and night, such as Villa Aldobrandini in Magnanapoli, whose entire nymphaeum was destroyed just in recent years. This is unbelievable.

Even sadder for those who, like you, saw Rome in the 1930s: a city, at least judging from the photos, still almost intact.

Rome was a beautiful city and we didn’t realize it. Beautiful, despite the fact that it had already been greatly ruined by the Piedmontese. It should not be forgotten that in thirty years, between 1870 and 1900, a third of the papal city was destroyed, with the demolition of monuments that anyone would have protected under glass because of their wonderful environmental and artistic beauty. The havoc of the Lungotevere, the destruction of San Salvatore al Ponte, Palazzo Altoviti, all the villas of the papal nobility: those of the Esquiline, Villa Palombara, Villa Ludovisi, Villa Altemps of which the beautiful central body full of ancient statues had been saved, then all beheaded, stolen, ruined by the horrendous stupidity of vandals, moreover perfectly symmetrical to that of those who left those treasures open to the public. Then the most serious disfigurement: the useless monument to Victor Emmanuel ll, which cost the gutting of the heart of Rome. When I think of Antonio Cederna’s chattering against “the blighted street of Via dell’lmpero!” Yet the polemicist Cederna never considered how the bieco stradone was the logical consequence of the monument to Victor Emmanuel II; and that perhaps, instead of destroying the former, the latter should be blown up. But already, the sacred monster of Piedmont is not to be touched; and with him I’Unità d’ltalia, the King Galantuomo, Camillo Benso Count of Cavour and all the others. Instead, they are the ones mainly responsible for the present debacle not only of Rome, but of the country. ltalia was not made by popular will. It was made by royal conquest. Mr. Victor Emmanuel II, King of Sardinia, did not even find the courage to call himself Victor Emmanuel I, King of ltaly. This alone is enough to understand how Italian unification went on, with the very serious consequences that came with it. This was a Nation that was based on internal repression and adventures abroad; and today, that internal repression and adventures abroad can no longer be done, it falls apart. As is only logical.

Missing from its sad list is Villa Pamphilj, whose devastation is most recent. The Doria princes, who owned it, had in fact kept it well enclosed and in perfect condition until thirty years ago, when it was expropriated from them.

Yet another damage brought to Italy by the cultural hegemony of a middle class of demagogic and moralistic intellectuals, aided by the perennial barricaded amateurism of cultural associations of the Italia Nostra type. No one then bothered to protect with day and night surveillance services the only European Baroque villa that miraculously remained intact until the mid-20th century. And within a month of opening to the public, the ancient marbles, inscriptions, statues, and fountains had all been stolen or broken with a hammer by vandals. But what mattered was “giving the green to the people.” Why then not take the illuminated codices and burn them to warm soup for the poor! The serious thing is not the good intention, but its amateurish implementation. After all, every country gets what it deserves.

One only has to think of how the city planning departments have reduced the suburbs of our cities.

Let’s not talk about it. What is Palermo without the Conca d’Oro anymore, obliterated by a shapeless congeries of thousands of condominiums, villas and cottages? What is Naples suffocated by the monstrous construction of the sack perpetrated on the city from 1945 to the present? What about the suburbs of Rome? Instead of having the city expand toward the sea to give it a boundary, as Mussolini wanted with his talented urban planners, it has been reduced to an immense Middle Eastern megalopolis, spreading in utter disorder from Tivoli to Ostia. What about the metastatic expansion of Milan, a city that now begins in Piacenza and ends in Varese? How then can the wonderful landscape of our sea coasts, destroyed by the criminal continuous row of hovels, cottages and casoni that have been built on it, from Trieste all the way down to Taranto and then up again to Ventimiglia, be compensated? What about Article 9 of the Constitution, which places the protection of the landscape as the ethical and moral obligation of the nation? They all didn’t give a damn, including the Ministry of Cultural and Environmental Heritage. Only to have everything come to a screeching halt. According to Italy’s immodifiable immorality, the political forces closed the matter by voting all together as one on the building amnesty law, and thus the havoc of Italy was made legal. An authentic disgrace.

This is the price Italians pay for having had a political class govern that is absolutely incapable of assessing the importance of the cultural problem for the civil progress of a nation.

Our political class has even trampled, vilified the cultural problem. I remember very well when Giulio Andreotti wanted to have an Ejzenstejn film banned or at least cut because there were depictions deemed impious of the Catholic Mass! Or when Palmiro Togliatti, after Doctor Zhivago was prevented from being published in Russia, said on television that it was a bad novel; or when posters with Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus were banned because its nudity was obscene! Do you not remember what a character like Mario Scelba was? Or of the slap given in public by Oscar Luigi Scalfaro to a lady with too much cleavage? The fire under the ashes of that explosion of ignorance, triviality, obscenity, which reign in Italy today. Even in public television! A truly unspeakable thing.

Nor do I think it will get much better if, as many hope, the management of the country’s cultural heritage is entrusted to private individuals?

If it is foundations that are the private individuals those many are thinking of, for goodness sake! A plethora of useless institutions that serve absolutely no purpose, poorly managed and almost all of them unfunded. A ballast for the state. While the banks’ foundations have too much money that they almost always spend senselessly. They pay hundreds of millions to buy a meaningless canvas by the usual “master of the sorcet” because it was recommended by a local connoisseur, and they spend nothing to buy really beautiful paintings or to finance very useful activities, such as would be, in the first place, that work of ordinary maintenance of the artistic heritage, which nobody does anymore, or that of cataloguing.

So are there no solutions to remedy the truly terrible situation you described?

Historically, it has been proven that the only way to make Italy work is to put it under foreign domination. So for the artistic heritage, the solution might be to put it under the tutelage of a Franco-English-German commission. For ltaly, in general, there would be two solutions instead, which I will not describe because I could get into trouble. I will only tell you that one is radical, the other very bloody. Nor finally would I rule out that another solution may come from the natural unfolding of things. In fact, I am convinced that if we go further beyond the minimum point already touched, the Nation may have an uncontrollable physiological motion of repulsion. Even violent.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.