This interview with Jacqueline de Jong (Hengelo, 1939), one of the most important contemporary female artists (she was part of the Situationist International publishing the magazine “The Situationis Times,” collaborated with the CoBrA group and for decades animated the Dutch art scene and beyond) was conducted by Juliette Desorgues and focuses on the so-called “Série Noire” (1981), which the artist exhibited this year at Artissima in Turin with the Dürst Britt & Mayhew gallery in The Hague. We would like to thank Dürst Britt & Mayhew for the valuable collaboration that allows us to offer to the Italian public this interesting interview, in Ilaria Baratta’s translation ( from here you can download the original). At this link you can find all the works of Jacquline de Jong from the Dürst Britt & Mayhew gallery.

Juliette Desorgues: Maybe we could start by asking you what led you to work on the theme of these postwar French detective novels, also known as Série Noire, for this series of works.

Jacqueline de Jong: When I lived in Paris [1960-1971, nda], I used to read the Série Noire. On every street corner, there was a kiosk where you could buy these novels. Anyway, I read many books from the Série Noire. In Italy you have the gialli. I loved very much the setting of these books, at that time completely devoid of pictures. Illustrating them was the main challenge I thought about. Not immediately, but years later, many years later, I bought only a few novels of the Série Noire, read the books and made the paintings, in my own bizarre style. It is interpretation. Some however are reality. But then why not bring some reality into some of them, as in the painting 30 maart 1981, which refers to the assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan?

What intrigued you about these books?

I found the history of the Série Noire itself fascinating. The founder of the series was an actor, playwright, translator and, I think, surrealist: Marcel Duhamel. His publisher, Gallimard, represented one of the biggest publishing houses in France and was very intellectual. He published, to take one example, the La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade series, a series of classics of world literature. But this series of books (the Série Noire) was extremely popular. Everyone on the street was reading the Série Noire. Instead of being reserved for intellectuals, it was the opposite. Duhamel was a vanguardist especially if you think of his film scripts he had decided to have Anglo-Saxon or American detective novels translated into French just after the war! Beginning in 1945 with his translation of the work of English writer Peter Cheney[La Môme Vert-de-gris and Cet homme est dangereux, nda].

It is quite ironic when you think how intellectual Gallimard is as a publishing house.

It is very ironic and also ingenious! Boris Vian actually translated some of the novels in the Série Noire.

I am interested in the artistic context in which you worked, in the late 1970s and 1980s when you were making these works. Before that, She was part of the Situationist International and Expressionism, but She was also close to Gruppe SPUR and the Fluxus movement. I wondered, with what other art movements did you feel an affinity at that time?

I belonged mostly to the Nouvelle Figuration movement, which in turn was influenced by the Free Figuration artists in France who emerged at that time. I was close to people like Eduardo Arroyo and many members of Nouvelle Figuration. I was also influenced by the painter Peter Saul. Of course, I was always interested in other people’s works. I left Paris around 1971. I didn’t leave France immediately, because I didn’t want to leave Paris, so I left little by little and wanted to bring artists I had known in France and Germany etc. to exhibit in Holland. But it was difficult. However, one or two galleries exhibited them.

What about with the art of other artists of the late 1970s and 1980s, such as Enzo Cucchi, from the Italian neo-expressionist group Transavanguardia? Did you have any affinity with their works as well for example?

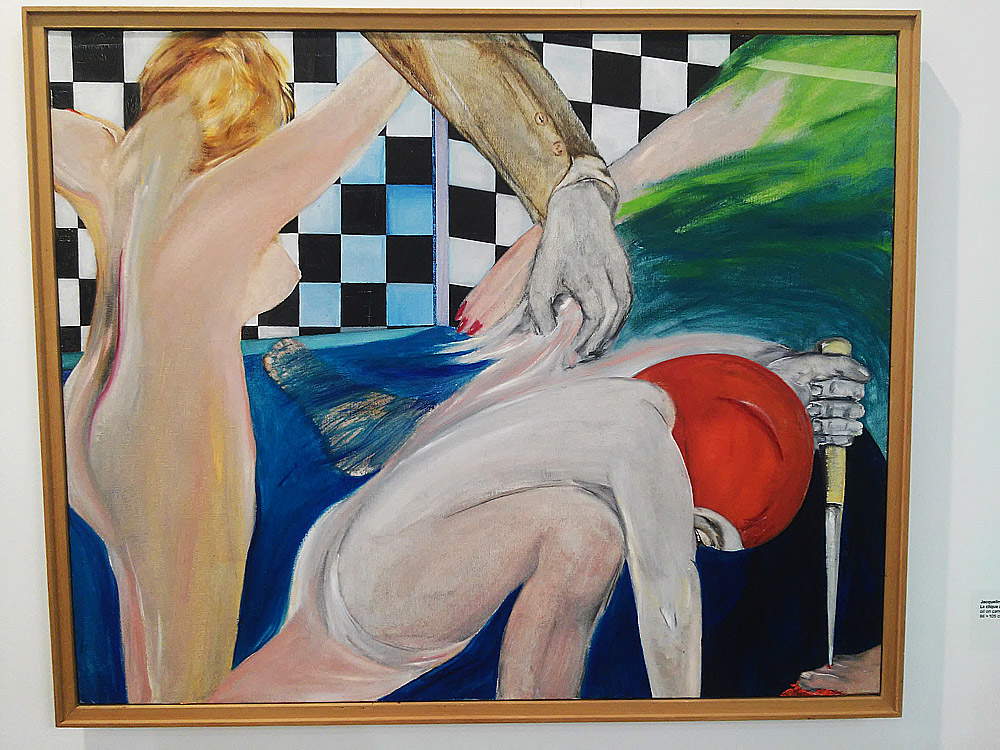

Definitely yes. There is a lot of similarity. People influence each other. But you know, I’m self-taught, since I didn’t go to the Academy. So it was kind of a challenge for me to create figurative paintings at that time. I like challenges, but it was kind of risky. For example, in this particular work, La Clique au Bassin [1981, ed.], I think I veered a little too far into surrealism.

|

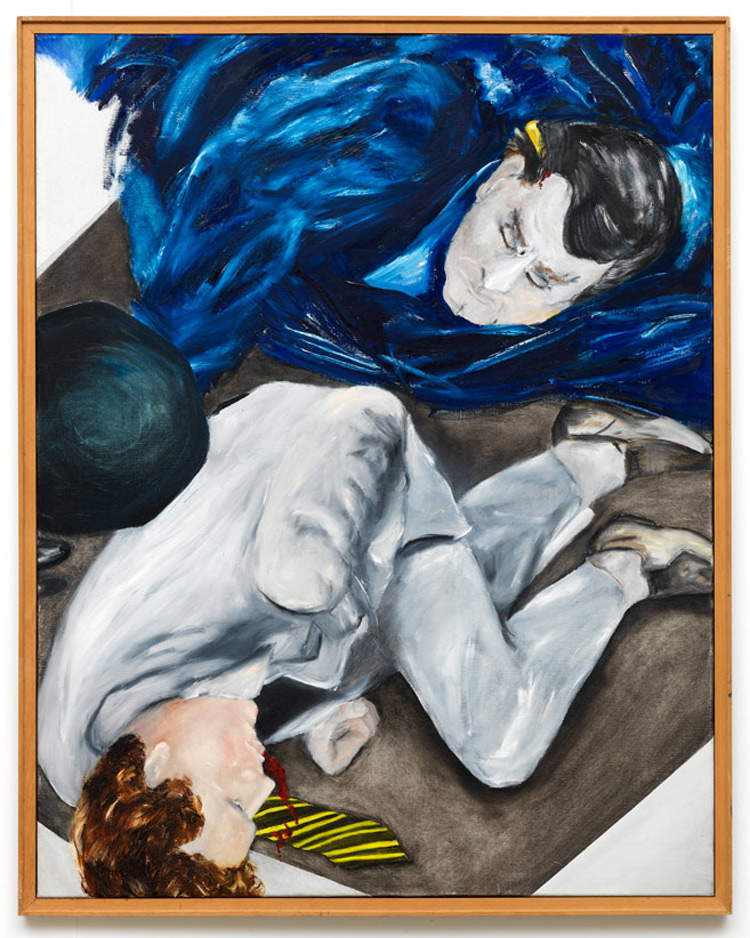

| Jacqueline de Jong, 30 maart 1981 (1981; oil on canvas, 120 �? 90 cm; The Hague, Dürst Britt & Mayhew). Courtesy Dürst Britt & Mayhew. |

|

| Jacqueline de Jong, La clique au bassin (1981; oil on canvas, 86 �? 105 cm; The Hague, Dürst Britt & Mayhew) |

It is interesting that you say that. This work for me is really the key to the whole series, in the sense that elements are present that are found in Your art the stoicism and sharpness of composition and color are disturbed by the movement of the hand. Like you hesitate between the expressionism of the beginning of your career and the realism that you are exploring at this time.

Yes, certainly.

There’s a lot of variety of style in this period, perhaps more than in any other-that’s what makes the series interesting, I think.

Oh, really? It’s not confusing?

Not at all. There’s also a very clear succession, starting with the Billiard series that you did in the late 1970s, in which you also experimented with figurative realist painting.

Yes. Elvis (3 generations) [1978, ed.] is in a way a transition to the Série Noire. But certainly in the Billiard series I began to be figurative and that was a challenge.

With the Billiard series there is an obvious shift toward a more hyperrealist form of painting, perhaps related to the wishes of Gerhard Richter, making a comparison with your earlier works.

Yes, certainly. You know that these kinds of figurative paintings fascinated me the most because I was not able to make them properly. So I simply tried.

So what pushed you toward this particular direction?

Well, in a way it’s quite simple. I was creating pinball machines in a very figurative style, and I was also working with figurative graphics. Then, Hans Brinkman, my partner, was always playing billiards, and that led me to this series. Simpler than that...

Another work that stands out among the Série Noire is Magic (1981), a Warholian pink gun.

Yes, but it was a joke. I was joking with the printer, and so I said let’s make a gun. I don’t remember for what reason I called it Magic. I had probably bought a small gun, made of plastic, called Magic. The Magic gun is obviously an erotic object. It is a screen print that was not really commissioned, but just made as a joke to the printer. Then people started to like it. We had fun making it. That’s all.

That’s why I consider it in a way the key to everything, because it seems to hint at some of the crucial interconnected themes in your art, such as violence, eroticism and humor.

Sure. I think I have been using them from the very beginning. Maybe it’s my theatrical side. Probably just to save myself or something. A way to introduce some humor into the art, to be a little ironic. I always say that if you wanted to recognize my paintings, just look for the eyes. Like the birds peeking in some of my small paintings. However, there is no real theater, I think.

Theater then is always undermined by humor.

I hope so and that it continues to be so in Série Noire.

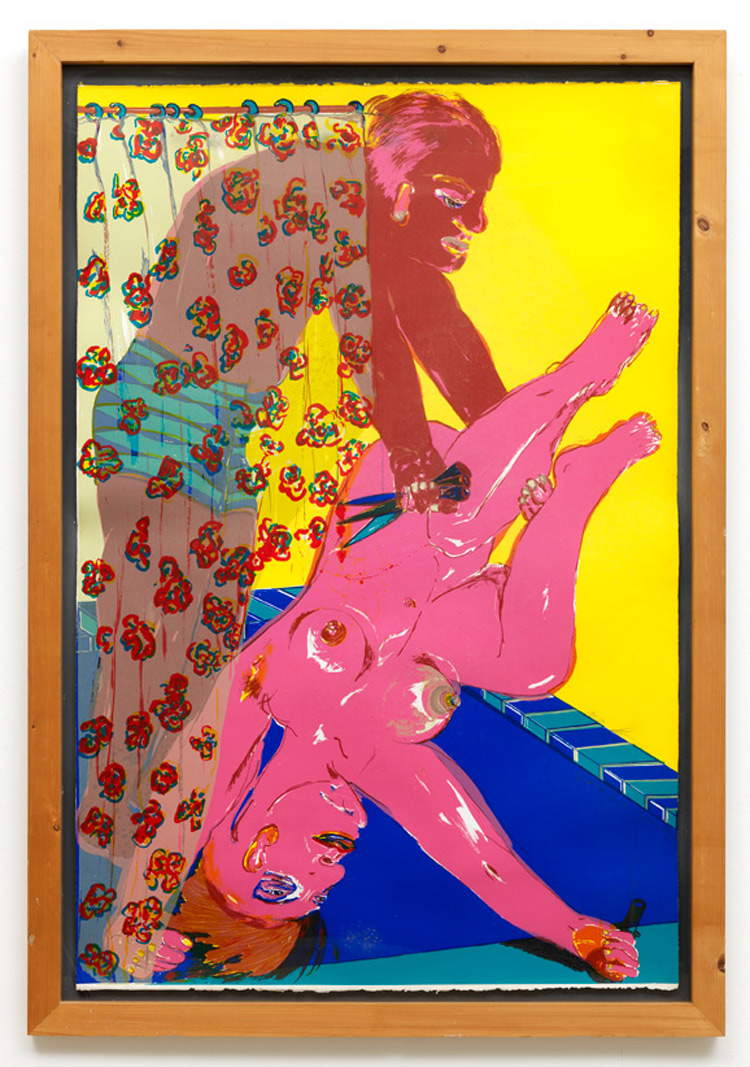

You also play with this in the titles of your paintings. There are often very humorous ones, like Quasy Modo and Queen Kong [1981, nda].

Yes, absolutely. The titles are very important. Although some are not mine. Some come from the books.

In fact, the text is the key to this series of works. The original book covers are black and white and without illustrations. But She through color translates the text onto canvas.

Yes and that really leads us to the Situationists, because the Situationist posters since 1968 are similar to book covers. They are without pictures. They are black and white and typographic. The posters I have made since 1968 contain very colorful images. They are absolutely the opposite.

I’m also intrigued by the idea that the detective novel is the quintessential storytelling and narrative, where there is a very clear and linear representation of time that follows the cause-and-effect pattern, and again he is completely going against that in his paintings. Close-ups and backgrounds disappear completely. Figures float on the canvases. There is no context.

There certainly is. There is invention in my paintings. But some deal with real commissioned crimes, as in Le professeur Althusser en étranglant Nina K (1981). Althusser was a Marxist professor who had murdered his wife. On the same day, Nina Kandinsky had been killed by a thief who stole her briefcase with jewelry. So there is indeed narration.

Yes, indeed, but you also took these two narratives and merged them through your own interpretation and imagination into this particular painting.

Yes, the painting Matt Helm sans guitar [1980, nda] really refers to Roman Polanski’s film Chinatown [1974, nda]. The figure wears a trench coat, the quintessential detective’s garment.

In Bleu Black Noir (1981), perhaps the most gruesome painting in the series, the figures appear to kill each other in an elevator. Where does this originate from?

No, nothing is taken from nothing! Or is anything taken from nothing?

This has actually been a common thread in His art. A sense of continuous reinvention. And perhaps this is then an apt point with which to conclude!

|

| Jacqueline de Jong together with Magic. Courtesy Dürst Britt & Mayhew. |

|

| Jacqueline de Jong, Quasy Modo and Queen Kong (1981; silkscreen on Japanese paper, 121.9 �? 81.3 cm; The Hague, Dürst Britt & Mayhew). Courtesy Dürst Britt & Mayhew. |

|

| Jacqueline de Jong, Le professeur Althusser en étranglant Nina K (1981; oil on canvas) |

Juliette Desorgues is an independent curator, writer, and editor who lives and works between the United Kingdom and France. She previously worked as an associate curator at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, where she curated several events, commissions, and exhibitions, such as in formation (2017), Helen Johnson: Warm Ties (2017), The Things that Make you Sick: Lorain Leeson and Peter Dunn (2017), Everything is Architecture: Bau Magazine from the 60s and 70s (2014), Bloomberg New Contemporaries (2016 and 2015), and Yuri Pattison: mute conversation(2014). Before that, Desorgues was curator at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, and Generali Foundation, Vienna.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.