For a woman, the profession of artist was very rare between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries because it was still considered male “territory”; however, female painters and sculptors defied the conventions of the era in which they lived in order to tenaciously follow their passion and to assert their skills with matter. And it is precisely to some of these women artists that the Giovanni Fattori Civic Museum has now decided to dedicate a new small display, entitled Strength and Determination - the artistic experience of women in the works of the civic collections, within the museum itinerary, exhibiting in the Salotto Verde works, both pictorial and sculptural, made by themselves, and portraits dedicated to women linked to the world of art, who dedicated during their existence a strong commitment to this sphere, made instead by men artists. These are all works that are part of the civic collection and testify to the presence of notable female artistic experiences at a time when this profession was anything but easy to undertake.

The audience is then welcomed into this intimate salon, characterized by draperies and verdant coverings, where pictorial portraits of several ladies stand out on the walls. We start with the Portrait of Giulia Capanna Taddei, a painting made in 1866 by Corinna Cresci Taddei. It is the oldest painting to have been executed by a woman among those belonging to Livorno’s civic collections. The dating of the work was arrived at from the date of birth of the effigy (July 18, 1826), although there is very little information about her, while there is no certain information about Cresci Taddei. The woman is portrayed seated frontally, clad in a luxurious black dress adorned with a fully embroidered collar and ample veils and lace on the sleeves. She holds her hands intertwined, and earrings and bracelets of red coral, for the manufacture of which the city of Livorno was famous in the past, stand out.

On display next to the portrait is a landscape by Leonetta Pieraccini Cecchi (Poggibonsi, 1882 - Rome, 1977), an important painter, illustrator and writer who came into the art world thanks to the Sartoni sisters, Florentine portrait painters, who gave her lessons. Leonetta was later a student of Giovanni Fattori at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence, where she trained as a portrait painter. In her career she won prestigious recognition by exhibiting at the Quadriennale in Rome, the Venice Biennale and the Permanente in Milan, and positive criticism from Giuseppe Ungaretti and Ugo Ojetti. The landscape exhibited is perhaps the painting that appears with the same title(Landscape. The Brick Factory) in the catalog of the Second International Art Exhibition of the Rome Secession in 1914.

We then continue counterclockwise with another portrait in painting: that of the painter originally from Finland Elin Danielson Gambogi (Noormarkku, 1861 - Antignano, 1919), who spent many years in Livorno. The painting was completed in 1905 by Raffaello Gambogi, her husband, who depicted her smiling, sitting in a red armchair, wearing a large hat on her head, and wearing a green blouse dotted with black roundels and a black skirt. The painter studied in Paris and then moved to Italy, when she was already an established artist who painted mainly female subjects busy at work or caught in private moments. The couple settled in Livorno, and here Elin had the opportunity to develop her luminous painting that looked to both the Impressionists and the Macchiaioli. She died at only 58 in 1919 and was buried in her adopted city.

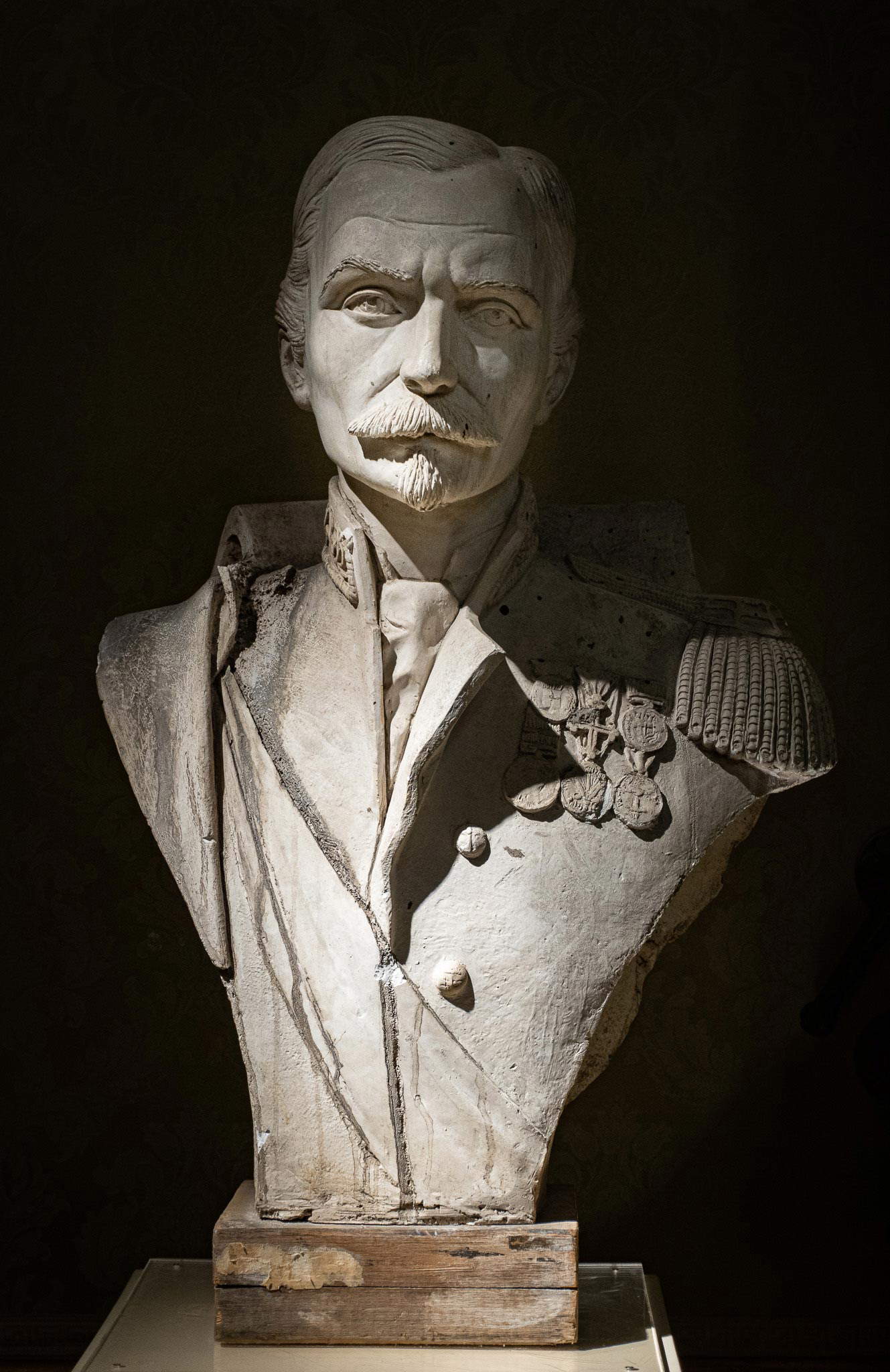

Moving to the center of the salon, the public can admire two sculptural works: a terracotta by Piera Funaro (Livorno, 1890 - Livorno, 1974) and another by Laura Franco Bedarida (Livorno, 1897 - Livorno, 1987). The first depicts the sculptor’s uncle, Livorno physician and man of letters Diomede Bonamici. Piera probably made the sketch with the intention later of making the sculpture with a more durable material; it was, however, published in 1931 in Liburni ’s magazine Civitas as a “sketch executed from life,” so it must have been made before her uncle’s death in 1912. If so, it would therefore be one of the oldest of the artist’s known works. Funaro is remembered for being the first woman to participate in the Gruppo Labronico , with which she exhibited since 1922; having moved away from verismo, she later moved toward more impressionist solutions, in the wake of Medardo Rosso. The second is a Head of a Child datable between 1940 and 1960 presumably made from a study from life as part of a production of private and introspective scope. Laura Franco Bedarida had her first lessons in painting from master Angiolo Tommasi; she approached sculpture around the age of thirty-five, taking lessons from sculptor Francesco Buonapace. Belonging to a prominent family of Jewish origin, he had to take refuge in France with his family members following the racial laws. It was during this time away from Italy that the artist made the plaster cast displayed here in the Salotto that depicts naval officer Alfredo Cappellini, a gold medalist in the Battle of Lissa, who died during a conflict with the Austrians by sinking with the battleship Palestro, of which he was in command. At the end of World War II, Franco Bedarida returned to Italy and gained important recognition, such as the acquisition of his works by the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Florence and by other major Israeli museums. She also received important commissions during her career, such as the bronze of Galeazzo Ciano, made when she was invited to Palazzo Chigi by the then Minister of Foreign Affairs.

The small itinerary dedicated to women concludes with a portrait of a great woman: the Livorno art historian Anna Franchi (Livorno, 1867 - Milan, 1954), to whom we owe the first biography on Giovanni Fattori. In addition to being among the first European art historians, preceding Margherita Sarfatti, she was the second woman to be admitted to theRegister of Journalists in Milan, preceded only by Filippo Turati’s companion, Anna Kuliscioff. Close to the Macchiaioli and post-Macchiaioli painters thanks to her acquaintanceship with the painters Angiolo, Ludovico and Adolfo Tommasi, pupils of Silvestro Lega, she was the author of important publications dedicated to these artists, and in addition to art and writing (to which she came after trying her hand at painting) she was also politically engaged. She fought for women’s rights: her novel Avanti il Divorzio on feminist issues dates from 1902. With the advent of the fascist regime, Anna Franchi interrupted her literary activity and public engagement and was forced to support herself by writing in beauty magazines. She later participated in the Resistance. She died in Milan in 1954 but according to her wishes was buried in her Livorno, which was always dear to her.

The portrait was executed in about 1950 by Giovanni Malesci (Vespignano, 1884 - Milan, 1969), Giovanni Fattori’s universal heir and author in 1961 of the Catalogazione illustrata della pittura a olio di Giovanni Fattori, the first attempt to reorder his pictorial production.

Underneath the painting, a display case holds, in addition to Fattori’s biography, Anna Franchi’s autobiography La Mia Vita, open to the page in which she mentions “the sketch of a portrait of my head” made in terracotta by Mario Galli, exhibited here, and his funeral mask.

A brief but intense dedication to these female figures linked to the world of art and to the city of Livorno between the 19th and 20th centuries, through works from the civic collection, which could (and should) be an opportunity for the launching of further studies and projects aimed at the knowledge and appreciation of these women of art, in particular to Anna Franchi, still too little valued in the exhibition itineraries related to the period. An exhibition itinerary that is in any case a good starting point for all museums to address gender issues, an aspect that is still not very concretely present within the permanent and temporary offerings of Italian museum institutions.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.