Here we go again: a “reckless” news story (that’s what I called it in La Repubblica), bounced around the press and television, complete with coverage on RAI, even the “Caravaggio” under the lens in Madrid has already earned it. An appendix detective story about an enigmatic affair in itself, which is worth talking about precisely because of the media prominence it has achieved. But also in order to highlight the comparison with when scholars of the caliber of Rossella Vodret (in the second part of this article) are instead unbalanced. Hypotheses, conjectures, opinions, counter-opinions, with extensive use of the conditional, are part of the DNA of the history of art criticism. But let’s rewind the tape.

While the most credentialed art critics, from Vittorio Sgarbi to Maria Cristina Terzaghi to Stefano Causa or Keith Christiansen, vie in the press for the primacy of the attribution to Merisi of the painting withdrawn from auction on April 8 at the Ansorena house, where he already had filed his expert opinion in favor of Caravaggio Massimo Pulini, published in part in “Avvenire,” and the Spanish government deciding to block its export, an Ansa launches the news of a “Sicilian track.” Until that moment, the question had been: canEcce Homo really be a work by the great artist that ended up in Spain and whose memory had been lost for centuries? The April 10 agency then launches this new question: could it be theEcce Homo from the collection of the Roccavaldina castle in Sicily? But on what elements would this new “Sicilian lead” be based? New compared to the one with which Roberto Longhi (1954) had forced Bellori’s testimony of an original painting for the “Signori Massimi,” suggesting to read “it was taken to Spain” extensively for Spanish domains and therefore Sicily. The reference, however, was to theEcce Homo in the Palazzo Bianco Museum in Genoa, several copies of which exist on the island.

|

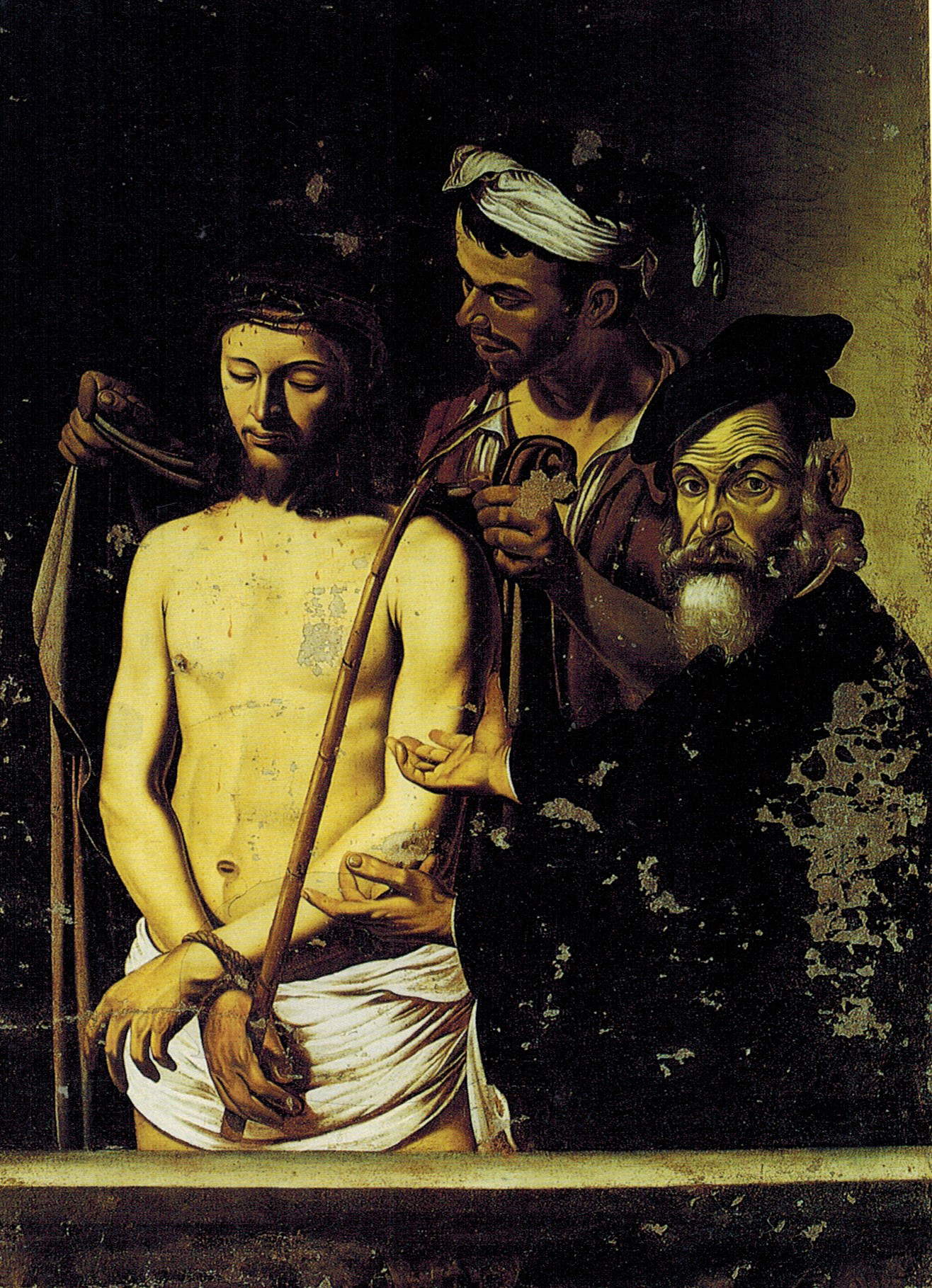

| Caravaggio (attr.), Ecce Homo (oil on canvas, 111 x 86 cm) |

The Sicilian trail that would lead to Roccavaldina is based, however, on nothing. Ansa reads, "Historical sources speak of an Ecce Homo (by an unknown author) owned by Prince Andrea Valdina, a native of Rocca Valdina, Messina. When the aristocrat died, his possessions were inherited by his son Giovanni, who drew up an inventory of the works in his father’s Palermo palace in the Kalsa district. These include a ’Christo with the cross in his neck’ by Caravaggio and an Ecce Homo attributable to the same cycle. Both paintings were transferred, in 1672, to the Castle of the Rocca. A few years later Giovanni Valdina left Italy for France. With the last prince the main branch of the family died out and the works were lost. The last records stop at 1676. That theEcce Homo may belong to the same author as the Christo is suggested by another element in the inventory: the two works both measure ’5 palms by 4,’ as Giovanni Valdina noted."

The hypothesis that theEcce Homo in Madrid may be the one that belonged to Valdina comes from a young Sicilian art historian, Valentina Certo, who delivered news about the collection in the province of Messina to the book in which she published her dissertation.

The new critical “geolocation” is so precise and timely... that it contains in itself elements that should have advised greater caution. In recalling the inventory drawn up upon the death of Prince Valdina, it is noted, in fact, that there is mentioned as by Caravaggio a Christ carrying the cross, while theEcce Homo is by anonymous. So, not even handed down as being by the hand of Merisi.

Now, you know that with this kind of inventory, you know that even the mere attribution to Caravaggio is not sufficient proof that it really was a Caravaggio, the practice being very common to increase the value of the collection with high-sounding attributions. Even the best of the Sicilian copies ofEcce Homo in Genoa, the one in the Regional Museum of Messina, before being traced back to Alonzo Rodriguez, had a long attribution to Caravaggio himself.

Moreover, according to this “Roccavaldina track,” numerical progression alone would be sufficient reason to correlate the “Ecce Homo” (No. 7) by an anonymous person to the “Christ Carrying the Cross” (No. 8) by an alleged Caravaggio; and to attribute both works to the same cycle. And to close the loop of a possibly Caravaggio on an alleged Caravaggio, the correspondence of measurements with the Spanish Caravaggio (?) (111 x 86 cm) is emphasized. Customary easel painting measurements. That is, we are not dealing with a large format such as that of The Burial of St. Lucy, to be clear.

We are, moreover, talking about works that have been lost, and of which no evidence has survived, not even indirectly. Nothingness, precisely.

In the absence of any other element, then, it was thought with the “Roccavaldina track” to tie also a very labile connection with the presence of copies or iconographic derivations present in Sicily. Punctual derivations, as for the remembered specimen in the hand of Rodriguez, from theEcce Homo of Genoa. Not of the one that appeared in Madrid. The name of Mario Minniti has also been mentioned. Nothing could be further from the concentrated power of the painting withdrawn from the Madrid auction by the versions of the Syracuse friend: one only has to juxtapose the panel withEcce Homo in the Cathedral Museum in Mdina (Malta) to realize how there is a sidereal qualitative distance. But also compositional: the lunge into the third dimension along the diagonal on which the three Madrid figures are arranged; the more ordinary flattening of Christ on the two men behind in the Minniti.

Three figures are not enough to stir up appearances. It is, in fact, part of the iconography ofEcce Homo (although it is used for works depicting the “Man of Sorrows,” with the solitary figure of Christ) the presence of Pilate uttering the phrase of mockery before Jesus, offered for mockery as a caricature of a king wearing a crown of thorns, a reed in his hand simulating a scepter and a red cloth parodying the emperors’ purple cloaks, and that of the henchman intent on covering his shoulders with the mocking cloak. It is no coincidence that Sgarbi’s critical eye on Il Giornale rested, immediately after the figures, on the parapet in the foreground, “a great and unprecedented spatial solution, for moral distancing from the horror and sickness of the turpent episode.” It is a functional element of the blatant scene, evoking the crowd of people witnessing Christ being brought out of the Sanhedrin and offered for mockery. A crowd that comes to coincide with the viewers of the painting, whose chattering can seemingly be heard contrasted with the concentrated silence of the protagonists.

For the setting of the figures within the scene, if anything, some suggestion can be found in the Genoese sphere. I am thinking of theEcce Homo in Gioacchino Assereto’s private collection, which goes beyond his usual exercises on Caravaggio’s texts to achieve here a tight gestural dialogue in which the hands of the three protagonists converge from near. Just as in the Spanish exemplar. It is a Caravaggesque figure that I dwelt on in my essay for the catalog of the exhibition Caravaggio. The Contemporary at the Mart in Rovereto: the mute language of gestuality, with which Merisi traces back in his works reality “simply,” as Brandi puts it, to its essential lines. Gesturality that can be connected within a triangular geometric pattern in many of his autograph works, as with these foreground hands of the Christ, Pilate, and Henchman in Madrid. It is here that the strength of the composition is condensed. Other than Minniti. It is no coincidence that the names of such masters as José de Ribera or Battistello Caracciolo have also been mentioned for the Spanish painting. But even to stop at a detail like the parapet is absent in Minniti. It is to be found in Cigoli’s version (in Palazzo Pitti, Florence) in the competition with Caravaggio for Massimi recalled by the sources, but also in the Genoese sphere itself: as well as in theEcce Homo in Palazzo Bianco, or in Assereto, even in his master Luciano Borzone, where, however, that Caravaggesque intention of the gestures, which the pupil seems to have made his own, is missing.

It is certain, however, that the game cannot be played on the ground of connoisseurship alone. More than for any other painter, the catalog recognized as autograph has now been abundantly subjected to diagnostic investigations. Such as the recalled Ecce homo from Genoa. Already not unanimously recognized as Caravaggio by critics, it is puzzling, however, that it could be “threatened” by the one in Madrid on the basis of an insufficiently documented thesis precisely on technical aspects. A 2003 restoration revealed several clues that would be from Merisi’s hand, including typical engravings. Insufficient clues, we said, for some scholars. Evidently ignoring this restoration, however, for Massimo Pulini these spy- grooves would not be present in the Genoese painting, unlike the Spanish one. So much would be enough for him to undermine the autography of this Genoese precedent. In short, others, and not just this one, would be the elements to be played out.

Here, then, is why never more than in this case is it worth prudently waiting for the diagnostic investigations to speak, before “leads” turn into red herrings. While in the meantime, Certo herself finally has... a way to clarify in a latest article in "The Ways of Treasures“ what she said journalists had misunderstood: ”it is not my intention to suggest leads or talk about detective stories“; the Madrid painting ”I have not seen it in person, so I cannot make any assumptions."

Evidently, it is not clear that what would have required more caution is not the attribution that has florid critics engaged, but that of having put up a hypothesis that rests on nothing, best to reiterate. This, "I think it’s important to know that there was an Ecce Homo attributable to Caravaggio at our place, too, and we don’t know where it went. It’s a little story that deserves to be told." But hadn’t he just finished saying that it was not his intention to suggest leads?

|

| Caravaggio (?), Ecce Homo (c. 1605-1610; oil on canvas, 128 x 103 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova - Palazzo Bianco) |

|

| Alonso Rodríguez, Ecce Homo (oil on canvas, 210 x 108 cm; Messina, Museo Regionale) |

|

| Mario Minniti, Ecce Homo (1625; oil on canvas; Mdina, Cathedral) |

|

| Gioacchino Assereto, Ecce Homo (c. 1640; oil on canvas, 124.5 x 97 cm; Private collection) |

It was worth telling this story, in order to understand what a gulf there is between a “reckless” hypothesis and the one that a scholar among the greatest experts on Caravaggio, Rossella Vodret, to whom we also owe a volume with the master’s complete works, has ventured to make. Just as, for that matter, other Caravaggio scholars have not been able to resist observing this or that detail, however, reserving their own accomplished judgment to the re-appearance of the cleaned and investigated painting.

But what was it that Vodret said? “I immediately had the feeling,” he explained in an interview with Federico Giannini, “that the figure of Pilate was a late self-portrait: we see an aged Caravaggio, slimmed down compared to the youthful self-portraits, however, in my opinion it is him, I don’t have many doubts.”

|

| Detail of Pilate’s face |

There is, however, one detail that might undermine this certainty. I came to it while subjecting myself to self-criticism first. In La Repubblica, mentioning Minniti, at first the physiognomy of the henchman behind Christ’s back had seemed to me to be that of Caravaggio’s friend and student painter. I had, however, later ended up writing that it might have been Caravaggio himself instead: ’To what we see in works such as the Burial of St. Lucy, the Dublin Capture of Christ, or the Martyrdom of St. Ursula in Naples could be juxtaposed the face of the young henchman who drapes the mocking purple cloak over Christ’s shoulders. ’It can only be Caravaggio’s,’ Maria Cristina Terzaghi observes (...). What if it is Caravaggio himself?"

Reflecting, however, while the article is still hot off the press, on which characters Caravaggio self-portrays himself in, either as protagonist or secondary subject, I have to revise my first impression: difficult to recognize one in the henchman. But, along the same lines of reasoning, also in Pilate. When, in fact, he appears alone as a protagonist, Caravaggio is wearing the guise of a mythological figure, such as the ailing Bacchus; in religious subjects, on the other hand, he is a Hitchcock-like extra, watching the scene, blending into the fray, as seen not only in the paintings mentioned above but also in the Martyrdom of St. Matthew. When, on the other hand, in a sacred scene he is one of the protagonists, then he is the victim: the Assyrian general Holofernes beheaded by Judith, Goliath beheaded by David, or St. John the Baptist decapitated by Salome. Would Caravaggio, then, ever have depicted himself in the shoes, be they of a Pilate or an anonymous henchman, of those who mock Christ? Frankly, it seems far-fetched as a suggestion.

Against the hypothesis of a self-portrait in Pilate’s shoes, there is, in addition, that detail I mentioned: a conspicuous mole on his right cheek, which does not appear in any of the recognized self-portraits.

In short, if it is not Caravaggio, we are, nonetheless, faced with such a mysterious work of art. And as we can see, insidious.

The author of this article: Silvia Mazza

Storica dell’arte e giornalista, scrive su “Il Giornale dell’Arte”, “Il Giornale dell’Architettura” e “The Art Newspaper”. Le sue inchieste sono state citate dal “Corriere della Sera” e dal compianto Folco Quilici nel suo ultimo libro Tutt'attorno la Sicilia: Un'avventura di mare (Utet, Torino 2017). Come opinionista specializzata interviene spesso sulla stampa siciliana (“Gazzetta del Sud”, “Il Giornale di Sicilia”, “La Sicilia”, etc.). Dal 2006 al 2012 è stata corrispondente per il quotidiano “America Oggi” (New Jersey), titolare della rubrica di “Arte e Cultura” del magazine domenicale “Oggi 7”. Con un diploma di Specializzazione in Storia dell’Arte Medievale e Moderna, ha una formazione specifica nel campo della conservazione del patrimonio culturale (Carta del Rischio).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.