If art is also catharsis of suffering, comfort for the soul as well as delight for the eyes, in this our time of sickness and death we have gone in search of examples of works of art in which pathology, sublimated, has ceased to conjugate with pain. Illness becomes an element that participates in an exquisitely harmonious, and therefore classically “beautiful” outcome, ending up establishing an aesthetic canon as well, as we shall see for Botticelli’s Venus. In the exercise of dialogue between different knowledge and expertise, we have thus subjected some works, famous and lesser known, to the “diagnosis” of a physician with a passion for art. Dr. Alessandro Raffa, a specialist in Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine, is one of the “angels” engaged in the front line of the Covid-19 emergency in the department of “Acceptance and Emergency Medicine and Surgery” at Arnas Ospedale Civico di Palermo. Perfected in Rheumatology and an expert in the same discipline at the University of Palermo, an area in which tocilizumab, a drug for rheumatoid arthritis, is being tested in the treatment of Coronavirus. This breakout in art, to which we have called him, we like to know has taken on a two-way “therapeutic” value.

Iconodiagnostics

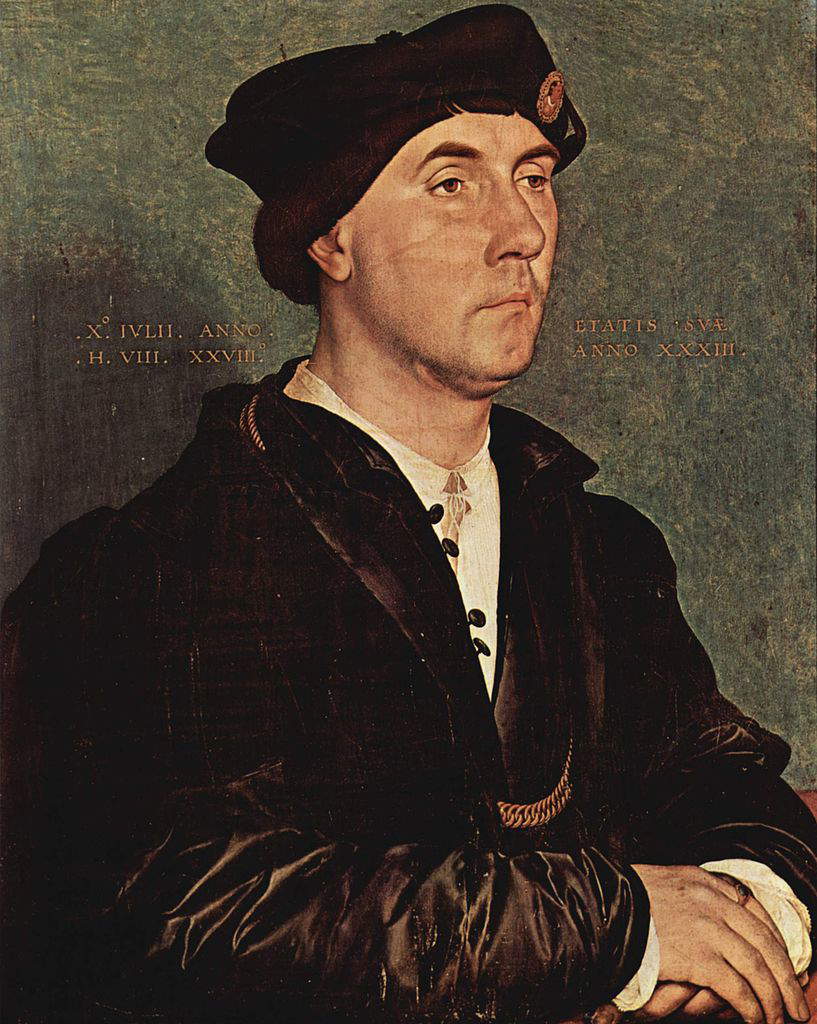

The “experiment” of interdisciplinarity, physicians-historians of art, has produced some interesting results (we point out Gian Carlo Mancini, L’arte nella medicina e la medicina nell’arte, Roma, 2008). For example, the Centro Studi GISED, a nonprofit association in the field of dermatology, recognized by the Lombardy Region, created a virtual gallery of skin diseases documented in works of art, which later became a traveling exhibition (“Art and Skin”). An original sampling that went on to unearth a melanoma on the temple of Mary Josephine of Bourbon, infanta of Spain, aunt of the king, in the Portrait of the Family of Charles IV (1800-1801) by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Fuendetodos, 1746 - Bordeaux, 1828); an angular cheilitis or boccheruola, an inflammation of the mouth, on the right side of the lips in the portrait The Old Woman (1506) by Giorgione (Castelfranco Veneto, 1478 - Venice, 1510); xanthelasmas, accumulations of fat in the eyelids in the Portrait of Clement VII with Beard (1527) by Sebastiano del Piombo (Venice, 1485 - Rome, 1547). Or, again, the scars seen in the Portrait of Sir Richard Southwell /1536) by Hans Holbein the Younger (Augsburg, 1497 or 1498 - London, Oct. 7, 1543) are due to a form of cutaneous tuberculosis also known as scrofuloderma; while it has been hypothesized that the dwarfism of a woman in the Bridal Chamber (1465 - 1474) by Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, 1431 - Mantua, 1506) may result from a genetic disorder, neurofibromatosis type I. Not just paintings and not just ancient art. In the vases of contemporary English sculptor Tamsin van Essen, the exterior workmanship resembles the skin surface affected by psoriasis.

|

| Franciesco de Goya y Lucientes, Portrait of the Family of Charles IV (1800-1801; oil on canvas, 280 x 336 cm; Madrid, Prado). Mary Josephine of Bourbon is fourth from the left |

|

| Giorgione, The Old Woman (1506; painting on canvas, 68.4 x 59.5 cm; Venice, Gallerie dellAccademia). Ph. Matteo De Fina |

|

| Sebastiano del Piombo, Portrait of Clement VII (1527; oil on canvas, 145 x 100 cm; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte) |

|

| Hans Holbein, Portrait of Richard Southwell (1536; oil and tempera on panel, 47.5 x 38 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

| The dwarf painted by Andrea Mantegna in the Bridal Chamber (Mantua, Castello di San Giorgio) |

Indeed, the initiative is most often taken by the medical world. There are several studies that consider art as a useful discipline for improving skills underlying the medical profession, such as one conducted by Sapienza University of Rome in 2016 ("Art and Medicine: from Vision to Diagnosis," edited by Vincenza Ferrara). Among the chapters is one dedicated to iconodiagnostics. The term was coined in 1983 by Harvard psychiatrist Anneliese Pontius to define practices useful for deriving information about an illness through images from art history. The psychiatrist was intent on demonstrating the presence of Crouzon Syndrome (a rare genetic disease) in the Cook Archipelago by examining ancient statues found there.

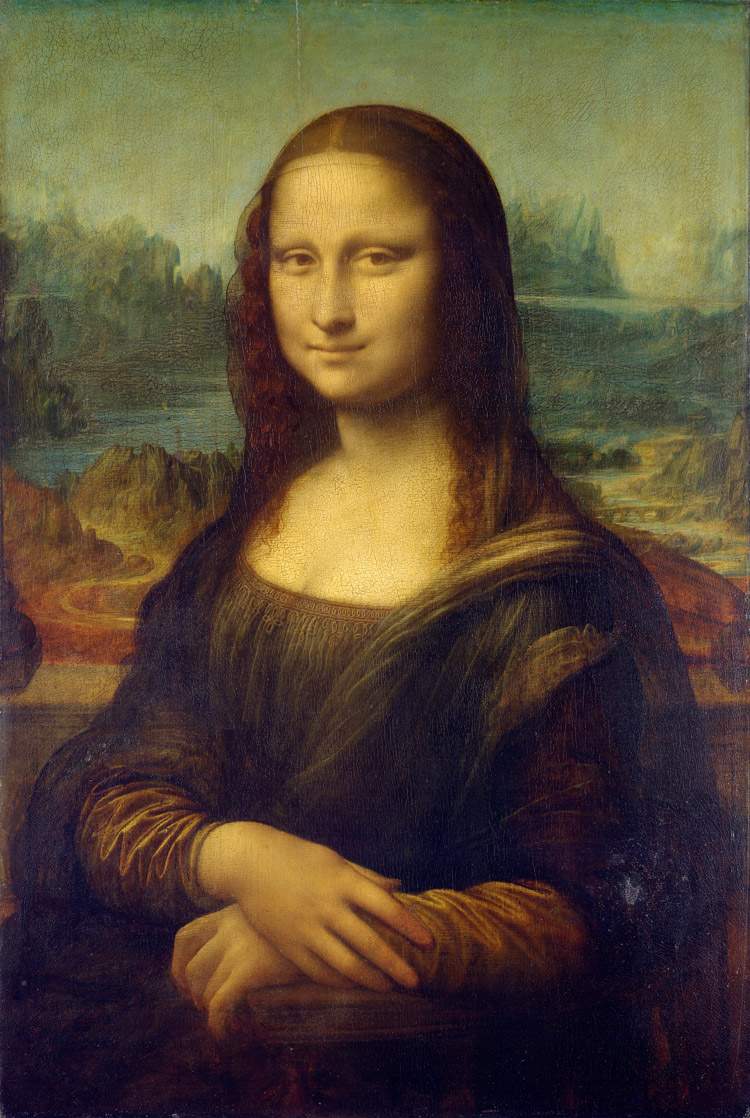

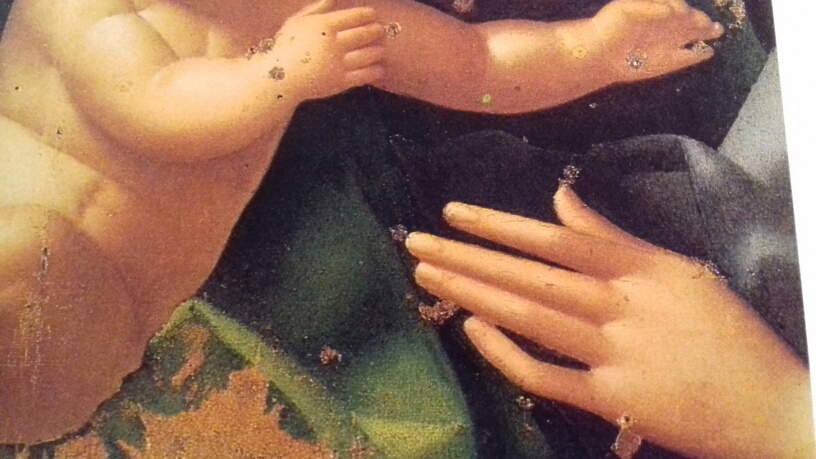

Various physicians have ventured into iconodiagnostics. Such as Vito Franco, professor of Pathological Anatomy at the Faculty of “Medicine and Surgery” at the University of Palermo, who “visited” a hundred more or less famous works diagnosing different diseases to the characters depicted. From arachnodactyly, from which the Madonna of the Rose (1530) by Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, known as the Parmigianino (Parma, 1503 - Casalmaggiore, 1540), is said to be affected, due to the disproportionately thin and elongated fingers compared to the palm of the hand, like the legs of a spider, to the hypercholesterolemia of the Mona Lisa (1503-1504) by Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) inferred from theaccumulation of fat under the left eye. For his theses that have in some cases destabilized art-historical studies, Franco also had the merit of provoking a critical debate, with Giorgio de Rienzo signing “L’inutile ricerca sulle malattie nelle occhi della Gioconda” (Jan. 6, 2010) in the “Corriere della Sera.”

|

| Parmigianino, Madonna of the Rose (1530; oil on panel, 109 x 88.5 cm; Dresden, Gemäldegalerie) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa (1503-1506; oil on panel, 77 x 53 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

The limitation of research of this kind lies, however, in looking at the works from a prevailing point of view, the medical one, which tests one’s powers of observation to delve into pathology in art history, marginalizing the eye of the curator, which is absent in most cases, to the detriment of effective interdisciplinarity. The risk, that is, is to consider the portrayed figures as individuals in whom blood flows, taking Mikel Dufrenne literally when he says that the aesthetic object is always a “quasi-subject”(Phénoménologie de l’expérience esthétique,1953, t. II, Paris, PUF, 1992). Not only that, generally, in American research, such as that edited by Professor Paul Wolfe, director of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the University of California at San Diego, the tracing of artistic outcomes back to the pathologies from which painters and sculptors were afflicted ends up marginalizing their creative vein, forgetting that the aesthetic object is not a mimetic representation of nature. Thus the massive predominance of the use of yellow in paintings such as The Chair with a Pipe (1888) by Vincent van Gogh (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890) is explained by theuse of foxglove infusion, used to treat the heart failure from which he suffered, which would have caused a distortion of color perception better known as xanthopsia, a condition that “makes one see yellow” due to intoxication with “digitalis purpurea.” While cataracts would be responsible for the extinction of form in paintings such as the various versions of the Water Lilies by Claude Monet (Paris, 1840 - Giverny, 1926). As can be seen, little room is left for understanding creativity, which, Hubert Jaoui states, “is not only imagination, fantasy or whim. It is also method, will, ’obstinate rigor’ as Leonardo da Vinci used to say”(L’Estro Creativo Creo dunque sono, 2009).

Returning from the artists to the works, there are those in which pathology is the overt protagonist. In Sick Child, of which there are several versions, in which Edvard Munch (Løten, 1863 - Oslo, 1944), the painter of the famous Scream (1893), evokes the loss of his sister, Sophie, who was cut down at only 15 years of age by a vicious tuberculosis. Sometimes these works acquire documentary value over time, such as the 1496 engraving in which Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528) attested to the outbreak of syphilis in Europe in the year following its first spread. The plague, seen as a punitive event for sinful conduct, is the subject of works that fulfill the function of ex voto, such as Palermo liberated from the plague, at the Museo Diocesano Palermo, painted around 1576 by Simone de Wobreck (Haarlem, ? - Palermo, 1558-1597). To remain still in Sicily, same function for a series of paintings with Scenes of Healing (second half 18th century), at the Capuchin Convent in Santa Lucia del Mela (Messina), published in 2011 by Luigi Giacobbe, assigning them to the Capuchin painter Fra’ Felice da Sambuca (Sambuca di Sicilia, 1734 - Palermo, 1805).

|

| Edvard Munch, Sick Child (1885-1886; oil on canvas, 120 x 118.5 cm; Oslo, Nasjonalmuseet) |

|

| Simone de Wobreck, Palermo Liberated from the Plague (c. 1576; 200 x 300 cm; Palermo, Museo Diocesano) |

Different, however, is the exercise in which we engaged with Dr. Raffa: going in search of pathology even when it is not the stated object of the work of art, catching it and diagnosing it through a detail. Discovering it even in the perfection of Renaissance art, to make a contribution together to the history of medicine and the history of art. And that is, not only to ascertain the manifestation of a disease, as done by iconodiagnostics on the work of Renaissance masters, such as Raphael’s Fornarina (1518 - 1519), in which a breast tumor would be depicted. Raffaella Bianucci, with colleagues at the University of Turin, published in “The Lancet Oncology” research on some works to follow the manifestation of such disease, such as La notte (1555-1565) by Michele di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio (Florence, 1503 - 1577), a transposition into painting of the similar figure sculpted by Michelangelo for the tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici, Duke of Nemours (1524-1534), in the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo in Florence, and L’allegoria della Fortezza (1560-1562) by Maso di San Friano (Florence, 1531 - 1571). Or again, Gilberto Corbellini, director of the Department of Social Humanities, Cultural Heritage of the National Research Council, explains that among the most probed paintings are those of Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen, 1577 - Antwerp, 1640), active for almost half a century, "there are at least three paintings in which he is said to have depicted breast cancer: The Three Graces, Orpheus and Eurydice and Diana and her Nymphs."

Coming, then, to our of research, when pathology is not exhibited in a work, it is as if the accompanying suffering has decanted. Where pain ceases, imperfection remains, absorbed in a dimension of prevailing harmony. Paraphrasing a famous exhibition curated by Salvatore Settis, we can say that "the strength of the Beautiful" also lies in its imperfection. A message that from art seems to be slowly passing also to that same fashion responsible for having imposed for generations an unattainable image of perfection: “imperfections” is precisely the name of the fall-winter 2020/21 collection on the catwalk at the Altaroma kermesse, signed for Morfosis by Roman fashion designer Alessandra Cappiello, who has behind her, not surprisingly, a background of classical studies and the influence of a painter grandmother.

|

| Raphael, Portrait of a Woman in the Clothes of Venus (Fornarina) (c. 1519-1520; oil on panel; Rome, Gallerie Nazionali dArte Antica di Roma, Barberini). National Galleries of Ancient Art, Rome (MIBACT) - Hertziana Library, Max Planck Institute for Art History/Enrico Fontolan |

|

| Michele di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, La Notte (1555-1565; oil on panel, 135 x 196 cm; Rome, Galleria Colonna) |

|

| Michelangelo, La Notte (1526-1531; marble, 155 x 150 cm; Florence, Sagrestia Nuova). Ph. Credit Andrea Jemolo |

|

| Maso da San Friano, The Fortress (1560-1562; oil on panel, 178 �? 142.5 cm; Florence, Galleria dellAccademia) |

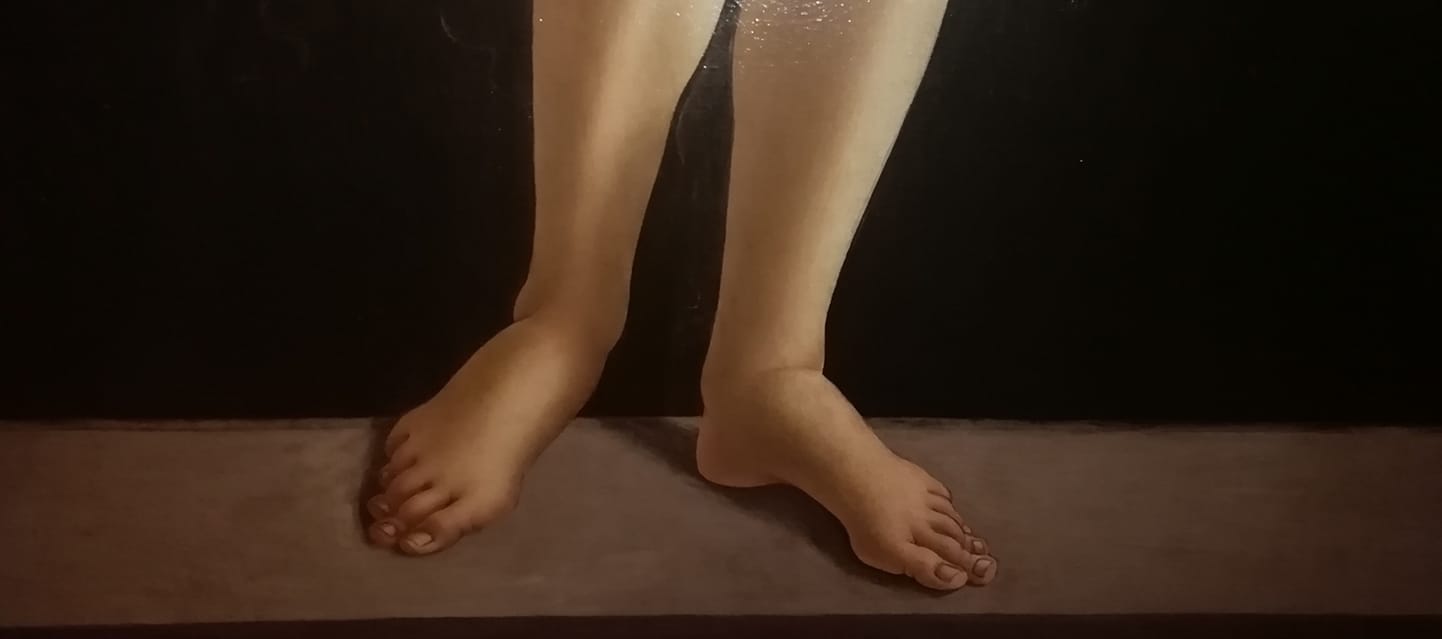

The flaw stands to a work of art like a slight deposit to a quality red. Think of the self-portraits of Frida Kahlo (Coyoacán, 1907 -1954), where hirsutism is a useful trait of masculinity that, in contrast, highlights the painter’s bursting femininity. Even in a Renaissance “icon” like Sandro Botticelli’s Venus (Florence, 1445 - 1510), there is “something wrong.” And it is not the well-known strabismus, hence the syntagma “Venus squinting,” a defect that has risen to a paradigm of sensual beauty. Not the fine eye of the connoisseur, but the gaze of “ordinary” visitors ended up being catalyzed by it: Aided by the useful location to cross it in the exhibition that, between last June and September, brought together in the Sale Chiablese of the Royal Museums of Turin the collection that belonged to the entrepreneur Riccardo Gualino, many were surprised to “discover” the decidedly graceless foot exhibited by the Venus (c. 1485- 1490) in the Galleria Sabauda, a version of the better-known Birth of Venus (c. 1485) in the Uffizi Galleries (two others are in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, 1490, and in a private Swiss collection).

We yield, then, the floor to our specialist. “In the Venus,” Raffa observes, “it is possible to notice an excessive accentuation of the height of the plantar arch of the left foot and a dorsal ’hump’; this is a ’hollow foot,’ which consists of a congenital malformation (imperfect development of the joints of the foot) or acquired by theuse of short footwear (the foot does not have enough space to stretch and tends to flex; if it were more contemporary high-heeled footwear would be determined by an excessive load of the body’s weight on the forefoot); other secondary causes recognize neurological and rheumatological pathologies as the basis.” He adds, “most notorious is the second toe that is longer than the others, which would reflect aesthetic canons of the time that harken back to Greek art; however, we could call it an ’anthropological foot,’ which is very reminiscent of the ’prehensile’ foot of the chimpanzee, as the same feature is found in primates.” Who would have thought! The goddess standing above the valva of a shell, pure and perfect as a pearl, has the foot of a primate (the foot is the same in the other versions). Moreover, appropriately Raffa mentions the compliance of this type of “prehensile foot” with the canons of Greek art. In addition to the famous demure attitude with which Venus covers her nudity with flowing golden hair, this detail is, therefore, also an indication of Venus’ derivation from the classical model of the “Venus pudica.” A figurative background to which Botticelli also looked for the pair of Winds flying embraced, a derivation from a Hellenistic-era gem that belonged to Lorenzo the Magnificent.

However, it is not always immediately possible to explain the appearance, in the compositional syntax of a work, of a lexeme indicative of pathology or trauma. For example, in the Triumph of Death (mid-15th century), a detached fresco preserved in the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo, Raffa observes “the hand with the last phalanx of the fifth finger fractured” in the Dominican corpse at the bottom center of the scene. A detail that has no functional reason of its own for the message the anonymous author wants to transfer, as, for example, with the derelict with the fractured and bandaged arm in the group of poor people on the left, who plead for an end to their suffering to Death, intent instead on shooting arrows that have already lethally struck popes and emperors. For that matter, one would be doing a disservice to the skillful hand of the probable transalpine master if one were to read it as a formal caving in. It remains, then, only to consider it, perhaps, a detail that accentuates the naturalistic character of the scene, on a par with the snappy line of the greyhound or the macabre anatomy of the horse that dominates the scene.

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Venus (c. 1485-1490; oil on canvas, 174 x 77 cm; Turin, Royal Museums, Galleria Sabauda) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Venus, detail. Ph. Credit Silvia Mazza |

|

| Roman art, Capitoline Venus, from original by Praxiteles (4th century BC; marble, height 193 cm; Rome, Capitoline Museums) |

|

| Unknown, Triumph of Death, detail (mid-15th century; detached fresco, 600 x 642 cm; Palermo, Regional Gallery of Sicily, Palazzo Abatellis) |

But let us return again to strabismus. If the one in Botticelli’s Venus is famous, our doctor also identifies it in “one of the greatest expressions of European painting of all time” (Mauro Lucco, 2006): theAnnunciation (c. 1476) by Antonello da Messina (Messina, c. 1430 - 1479), in Palazzo Abattelis, Palermo. Raffa identifies “a slight convergent strabismus of the left eye: the left eyeball is more oriented inward than the right eyeball is toward the outer corner.” “This is,” he explains , “a defect of convergence of the visual axes of the two eyeballs and is due to a lack of coordination between the muscles involved in the motility of the eyeballs (extrinsic muscles) preventing the gaze of each eye from being oriented on the same lens.” The “defect” in this case can be considered functional in the construction of the image and its thoughtful “concept.” It participates, no less than the gesture of the hand reaching toward the viewer and the other clasping the mantle, in the revolution by which Antonello eliminated the figure of the angel, presupposed by the Annunciation itself. Our Lady does not need, in fact, to “direct her gaze on the same target,” she does not look for “someone” before her; the breath that lifts the pages of the book on the lectern, a sign of the presence of the Holy Spirit, she cannot see, only feel. This slightly squinting, lost look is an introspective gaze; it contributes to the Virgin’s distancing to a superhuman elsewhere. There is a sidereal distance between the instinctive motion of that hand that stops what it does not yet know and at the same time reaches out along a perspective that spans the centuries to reach all humanity, and the absence of that gaze, rapt in a dimension of awareness and acceptance.

Antonello again, again a detail that participates as an active component in the figurative construction. In this case it is the Polyptych of St. Gregory (1473), at the Regional Interdisciplinary Museum of Messina, still a novelty, in structure and conception, precipitated by Antonello in the panorama of the time. “The figures portrayed from below up as they would in fact appear if hoisted up there in the flesh” (Marco Collareta, 2006) are functional to the realistic representation of attitudes in a spatiality linked by a unified perspective effect. The latest restoration, on the occasion of the major anthological exhibition on Antonello da Messina held at the Scuderie del Quirinale in May 2006, revealed just below the mouth of St. Gregory a small scar, “which is worth making it a living creature, with its own history behind it” (M. Lucco, 2006). With this meaning we might also consider a detail that has escaped the eye of art historians. Raffa notes, in fact, “a probable congenital malformation of the thumb of the left hand,” the one that hands the cherries to the Child. A “defect” that belonged, perhaps, to the one who modeled for Antonello.

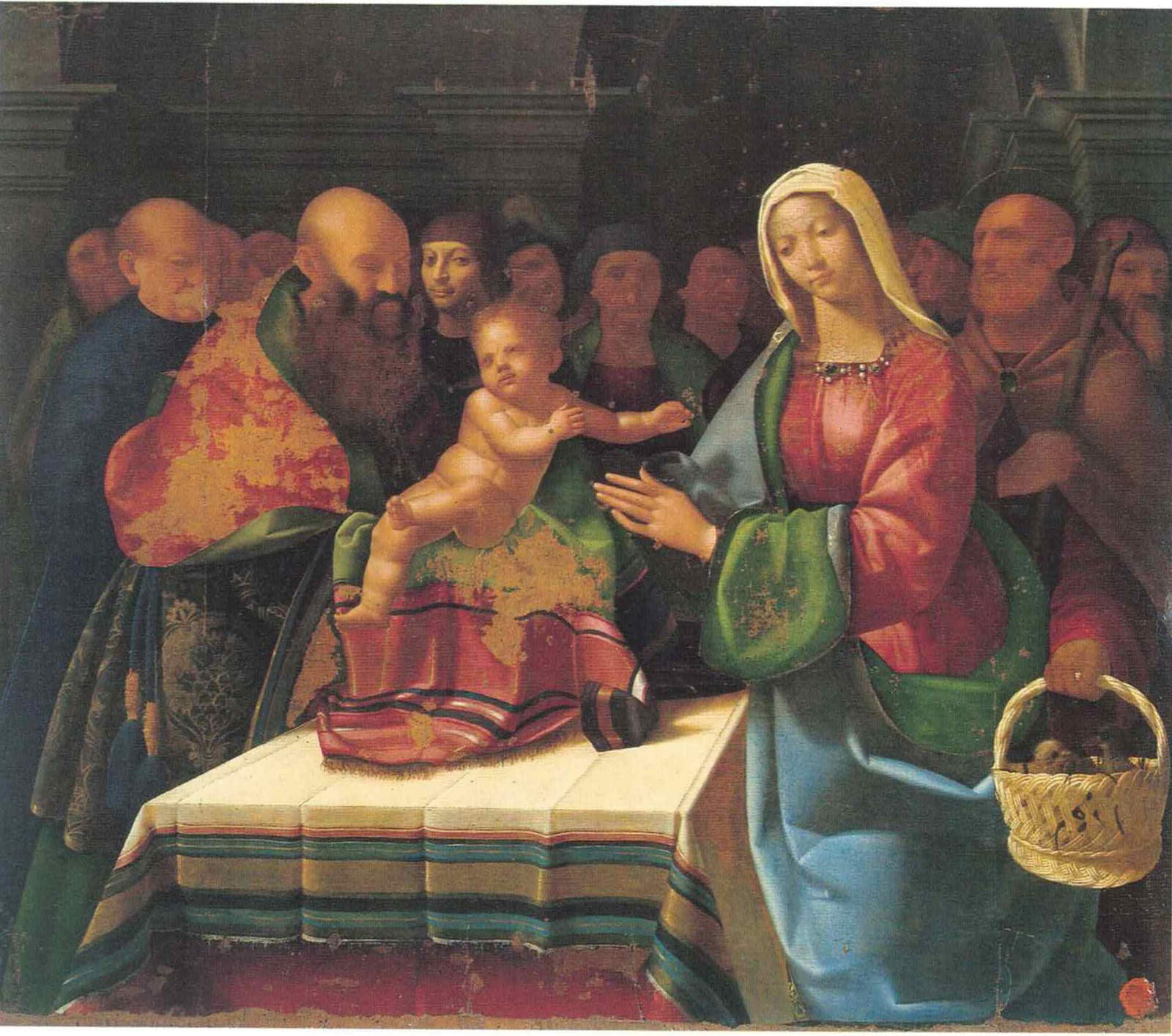

Another Renaissance hand, another defect. In the Circumcision (1510) by the Messina-born Girolamo Alibrandi (Messina, c. 1470 - c. 1524), still in the museum on the Straits, that of the Madonna is “a hand with clinodactyly,” Raffa notes. “This is a congenital malformation characterized by permanent curvature in the medial or lateral location of a finger or phalanx (the fifth finger is usually affected). Clinodactyly can occur as an isolated abnormality or in combination with other malformations in some genetic Down syndromes, Klinefelter’s and Turner’s syndromes.”

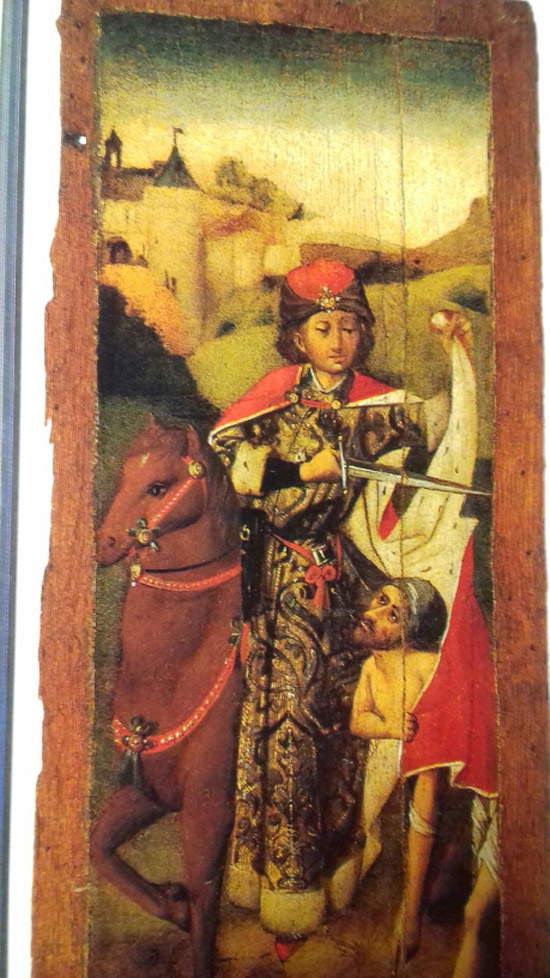

Things get more complicated in the triptych flap by an unknown Flemish artist (16th century), also at the Messina Museum. In the panel with St. Martin gives his cloak to the poor man, the latter appears to be “suffering from harmonic dwarfism , a condition,” Raffa explains, “due to congenital deficiency of growth hormone produced by the pituitary gland; all the parts of the body are reduced in size, in a harmonic way.” A diagnosis that opens up not a few problems. In the iconographic tradition, in fact, no other version can be found in which the beggar with whom St. Martin of Tours shares his cloak is a dwarf. Nor can the reduced size be given the symbolic value of the traditional hierarchical distinction between the figures, apt to emphasize the humble condition of the poor man compared to that of the saint, because this is achieved by a proportional shrinking of the figure. Here, however, we are in the presence of a dwarf. But there is more. A close look at the figure reveals obvious anatomical contradictions: while the head torso and the arm with the hand grasping the cloak respond to the doctor’s reading, the slender legs and the other arm, long and outstretched like a stick, are out of proportion, disjointed; it is as if they belong to another individual, although critics have read it as a single figure (“the poor man is naked, covered only by a cloth that encircles his hips,” B. Ferlazzo, 1991). An attempt to represent a second beggar? The latter appears in other paintings, in which the summer legend is grafted onto the main episode, according to which Martin later meets another beggar and decides to give him the other half of his cloak as well, thus remaining exposed to the elements. But in our table, the Saint-illusionist’s cloak makes his upper body disappear! A detail, in the end, that is difficult to explain in the economy of a work that appears well-proportioned in all its components, except by thinking of repentance. In this case, the diagnosis is a real puzzle offered to the art historian.

|

| Antonello da Messina, Annunciation (c. 1476; oil on panel, 45 x 34.5 cm; Palermo, Regional Gallery of Sicily, Palazzo Abatellis) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Annunciation, detail |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Polyptych of St. Gregory (signed and dated 1473; tempera grassa on panel, 65 x 62 cm; 65 x 54.7; 125 x 63.5; 129 x 77; 126 x 63; Messina, Regional Interdisciplinary Museum) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Polyptych of San Gregorio, detail |

|

| Girolamo Alibrandi, Circumcision (1519; tempera on panel, 99 x 118 cm; Messina, Museo Regionale Interdisciplinare) |

|

| Girolamo Alibrandi, Circumcision, detail |

|

| Unknown Flemish artist, Triptych doors with St. George and with St. Martin gives his cloak to the poor man (oil on panel, 67 x 27 cm; Messina, Museo Regionale Interdisciplinare) |

|

| Unknown Flemish painter, Hatches with Saint Martin gives his cloak to the poor man, detail |

Michelangelo: the temper of Genius as anesthetizer

And we close the roundup by diagnosing this time the pathology of an artist. One of the greatest of all time: Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564). In this case Raffa moves into the territory he is most familiar with, that of rheumatology, on the one hand to clarify and develop what has already been found in a recent study, offering it to a different art-historical reading, and on the other hand pointing out another pathology that has not been recorded so far.

An Italian study that appeared in 2016 in a medical journal (Davide Lazzeri, Manuel Francisco Castello, Marco Matucci-Cerinic, Donatella Lippi and George M. Weisz, “Journal of the Royal Society of Medecine”; 2016, Vol. 109 (5), pp. 180-183) analyzed three portraits of Michelangelo - the one made by Jacopino del Conte (Florence, 1510 - Rome, 1598) in 1535, the one attributed to Daniele da Volterra (Volterra, 1509 - Rome, 1566) dated 1545, a probable copy from Jacopino, and the posthumous portrait made by Pompeo Caccini (Florence 1577 - Rome? c. 1624) in 1595 - to arrive at the conclusion that the joints of Michelangelo’s left hand were affected by arthrosis, a condition that would have struck him around age 60. Thus would be explained the loss of dexterity in old age, but also his victory over the disease (“one plausible explanation for Michelangelo’s old age loss of dexterity, emphasising his triumph over infirmity”), having managed to continue using his hands until the last days of his life. Like Pierre-Auguste Renoir (Limoges, 1841 - Cagnes-sur-Mer, 1919), who was struck late in life by a violent deforming arthritis that did not prevent him from executing great paintings such as The Bathers (1918-1919).

For Raffa, who confirms the diagnosis, the “patient,” however, appears more seriously compromised. “Although initially assumed, other scholars (D. Lazzeri, M. F. Castello, M. Matucci-Cerinic, D. Lippi and G. M. Weisz, cit.) have not confirmed that Michelangelo was suffering from a uratic arthropathy (’gout’), but rather from arthrosis,” but adds, "however, compared to the study cited above, particularly the portrait done by Jacopino del Conte highlights the artist’s left hand, which appears to be affected by ’primary osteoarthritis.’ This is a degenerative arthropathy of the joints of the hand that manifests itself in a somewhat more aggressive form than ’classic arthrosis’ and causes greater joint damage and functional limitation.“ ”In particular,“ the specialist further specifies, ”in the portrait a primary osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal and proximal interphalangeal joint of the first finger is well evident; the same can be said of the metacarpal-phalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the second finger and the proximal interphalangeal joint of the third finger, which is glimpsed."

Possible causes for Raffa: “the continuous stress on the joints of the hands by the jerks induced by the use of the hammer and chisel, and Michelangelo being left-handed, it is also possible that the hand most stressed was precisely the left hand because it was with that that he held and threw the hammer blows on the chisel, the latter held by the right hand. Likewise, neither is it possible to overlook the activity of ’painting’ with the paintbrush and with precision for several hours a day, because this activity represents a continuous strain on both the joints and the tendons and sheaths that cover them and that can become inflamed.”

The inferences that can be made from this new diagnosis of increased aggressiveness of the disease are not insignificant. The 2016 study concludes with the thesis that continuous and intense work could have helped the Master to keep the use of his hands as long as possible (“the continuous and intense work could have helped the Master to keep the use of his hands as long as possible”). An argument that with Raphael we can say finds no scientific basis: “difficult to work with inflamed and sore hands,” “possible to assume the use of a phytotherapeutic extract based on salicylates, already known at the time to soothe ’pains and fevers.’” While it is more plausible to imagine that the enormous willpower, the temper of genius acted to some extent as an anesthetic to the most excruciating of pains. A proof of the therapeutic value of artistic exercise. And that an elderly Michelangelo was highly motivated is also suggested by the fact that until a few days before his death he was working on what is not only his last work, as recalled in the recalled study, but his testament carved in marble, the sculpture to be placed on his tomb: the Rondanini Pietà (1552 - 1564).

|

| Michelangelo Buonarroti, Rondanini Pieta (c. 1555-1564; marble, height 195 cm; Milan, Castello Sforzesco) |

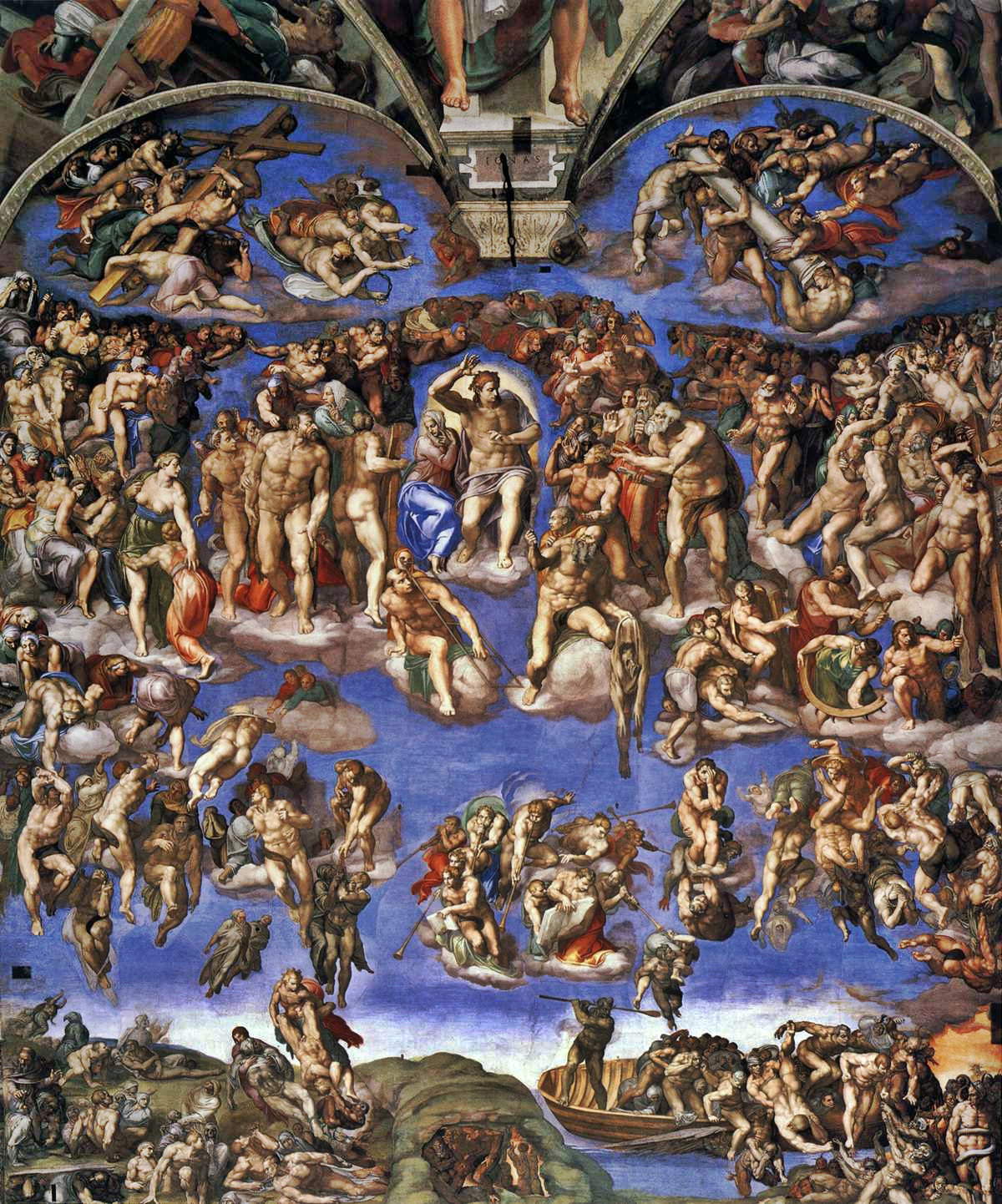

But that is not all, we said. The same study also refers to the portrait of Michelangelo in the guise of Heraclitus in the School of Athens (1509-1511), in the Sala della Segnatura, with which Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520) wanted to pay homage to the Master, who in those same years was painting the Palatine Chapel, in particular the Genesis frescoes (1508-1512). The reference to the portrait is useful to specialists in documenting that at that time, when Michelangelo was between 34 and 36 years old, his hands showed no signs of the pathology that would affect him thirty years later (“his hands appear with no signs of deformity”). Taking a closer look, however, Raffa identifies something else wrong. "In Raphael’s portrait of Michelangelo, the right knee appears with deformities typical of arthrosis; the left knee appears in better condition." Not only a hand, then, but also a knee. For the doctor, this early arthrosis would have been due “probably to the continuous/discontinuous resting of the knees together or alternately on a hard surface, during his work, which could have caused meniscal lesions with intercurrent inflammatory episodes of the knee exiting into arthrosis.”

Previously, the aforementioned Vito Franco had also noticed this knee, but had speculated uric acid deposits, in line with the traditional thesis that the master was suffering from gout, later overcome by the 2016 research. But wanting to disregard even the latter, Raffa still observes, “the knee is not a preferred site of gout, the big toe or ankle being major sites.”

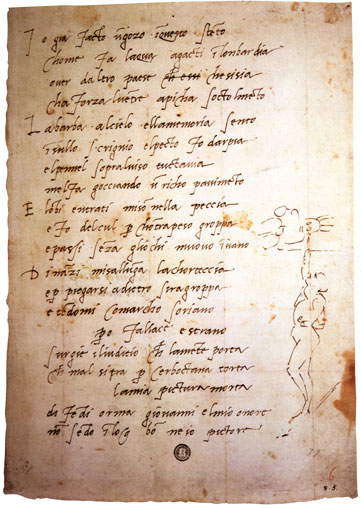

It remains at this point to verify whether the diagnosis of an early arthrosis of the knee is compatible with Michelangelo’s working biography, given that, for the balance of the limbs and the stability of the whole body, we can well imagine that the position of the left arm with which he beat the hammer blows on the chisel corresponded to the right knee resting on the ground. Indeed, there is no doubt that between the ages of 34 and 36, he was an accomplished sculptor, so much so that he received a commission from Pope Julius II in the Sistine Chapel to decorate the back wall with the Last Judgment and the vault with episodes from Genesis. By that time he had already made, to name but a few, the Bacchus (1496-97), the Vatican Pietà (1497-1499), the David (1501-1504), the Pitti Tondo (1503-1505) or the Taddei Tondo (1504-1506). Sculptural works for whose execution he had been able to keep his knee pointed at the floor in a prolonged way. But in the years when he was working on the Sistine Chapel vault, between 1508 and 1512, could he have assumed that position, contributing to the wear and tear on the knee observed by our doctor? We know that it was four years of physical as well as inventive effort that caused no small damage to the Master’s health: 1,010 square meters of painting, hundreds and hundreds of figures. What was the prohibitive position in which he painted is documented by a sketch (in the same sheet as an autograph sonnet preserved in Casa Buonarroti, Florence) of himself while head up sketching a figure. In addition to standing, we know that he also painted lying down. But he must also have done so while bending or kneeling, precisely, as the scaffolding he himself devised (which Ascanio Condivi and Giorgio Vasari write about) suggests, in order to solve the twofold problem of allowing him to reach the ceiling, but at the same time allowing the regular flow of religious and ceremonial activities in the chapel. This consisted of a “stepped” hanging scaffold, hung from supports cut from holes in the walls, such as to allow him to work on the various surfaces in different positions. Along with the curvature of the vault, this very structure also suggests the adoption of a kneeling position, for example to paint the sails or lunettes: it consisted, in fact, of a central platform from which the artist made the stories of Genesis and the Ignudi; side tiers from which he painted the series of the Seers and that of the sails; while from another platform, which ran at the base of the bridge and could be accessed by removing the boards of the tiers, he frescoed the Ancestors of the lunettes.

|

| Michelangelo Buonarroti, Verses with self-portrait in the act of painting the Sistine vault (1508-1512, pen; Florence, Archivio Buonarroti, XIII, fol. 111) |

|

| Michelangelo Buonarroti, Last Judgment (1536-1541; fresco; Vatican City, Sistine Chapel) |

There is still one question to be clarified. How had Raphael been able to see Michelangelo’s knees? Unlike the other philosophers dressed in old-fashioned clothing, he has Michelangelo in the “shoes” of Heraclitus wearing contemporary clothes. Including the well-worn boots he used to wear and never take off, as Condivi recounted in 1553 in his biography: he wore “di continovo dog-skin boots over the ignudo the whole months, that when he wanted to pull them off, then in pulling them off the skin often came off.” While according to the fashion of the time, men wore stockings that reached just above the knee. That the anatomy of the legs (naked or wrapped in a stocking) was visible is also documented in the sketch already mentioned, in which Michelangelo portrayed himself in the position in which he used to paint the vault of the Palatine Chapel. That the master was “obsessed” with boots also finds confirmation in the famous episode of his fall from the scaffold on December 15, 1540, when he was working on the Last Judgment (1536-1541), which forced him to remain locked in his house for quite some time. After treatment that got him back on his feet, he had to believe in some sort of miracle so much so that he made a singular vow: one whereby he would not take off his boots again for a year.

Returning, then, to Raphael’s portrait, the boots appear shod right on his bare skin. Everything suggests, then, that in this faithful rendering of the rival’s image, our knee with arthritis was also a realistic detail.

In conclusion, Michelangelo’s very “case” indicates in what direction the exercise of dialogue between different disciplines and skills can be understood: if a physician who challenges himself by formulating a diagnosis from the mere observation of a painting must take into account that art implies an exegesis that prescinds from the physical datum, the art historian must be ready to question even well-established studies, with the intention of endorsing a medical reading that can make an artistic parable rewritten, or on the contrary to refute it if it risks being a forced over-interpretation. After all, physicians and painters share the same patron, Saint Luke.

The author of this article: Silvia Mazza

Storica dell’arte e giornalista, scrive su “Il Giornale dell’Arte”, “Il Giornale dell’Architettura” e “The Art Newspaper”. Le sue inchieste sono state citate dal “Corriere della Sera” e dal compianto Folco Quilici nel suo ultimo libro Tutt'attorno la Sicilia: Un'avventura di mare (Utet, Torino 2017). Come opinionista specializzata interviene spesso sulla stampa siciliana (“Gazzetta del Sud”, “Il Giornale di Sicilia”, “La Sicilia”, etc.). Dal 2006 al 2012 è stata corrispondente per il quotidiano “America Oggi” (New Jersey), titolare della rubrica di “Arte e Cultura” del magazine domenicale “Oggi 7”. Con un diploma di Specializzazione in Storia dell’Arte Medievale e Moderna, ha una formazione specifica nel campo della conservazione del patrimonio culturale (Carta del Rischio).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.