And wanting Monsignor Massimi an Ecce Homo that would satisfy him, he commissioned one from Passignano, one from Caravaggio and one from Cigoli, without the knowledge of the other; all of which, having been finished and compared, he liked his more than the others, and therefore keeping it with him while Monsignor stayed in Rome, it was then taken to Florence and sold to Severi.

These are the words that have handed down to us one of the most famous"competitions" in the history of art. It is 1605: judge of the competition and patron of the works is Cardinal Massimo Massimi, a Roman prelate of noble birth. The three contenders are three of the greatest artists of the time: Michelangelo Merisi known as Caravaggio, Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli, and Domenico Cresti known as Passignano. All three curiously share the commonality of having, by nickname, the name of a small town: their birthplace for Cardi and Cresti, their mother’s birthplace for Merisi. The competition consists in proposing to Massimo Massimi a painting having for its themeEcce Homo, or the moment in the Passion of Christ in which Jesus, after being scourged, is presented by Pontius Pilate to the people to demonstrate the scourging. The phrase “Ecce Homo,” in Latin, means precisely “behold the man”: the episode is recorded in the Gospel of John. The painting deemed best by Massimo Massimi will win the"competition."

|

| Caravaggio, Cigoli and Passignano |

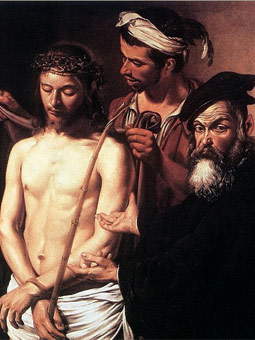

Caravaggio’s painting, now housed in the Palazzo Bianco in Genoa, shows a suffering but peaceful Jesus because he already knows what his fate will be. He has already undergone the crowning with thorns and holds a reed, which was placed in his hand as a scepter to mock him whom people hailed as the King of the Jews. A servant, depicted with excellent realism, is covering his back. Pontius Pilate is on the right, with a natural expression, stern but looking at the observer with an almost questioning air, perhaps wondering if the punishment is really what Christ deserves. Both the servant and Pontius Pilate are dressed in modern garments, a typical feature of seventeenth-century art.

|

| Caravaggio’s Ecce Homo, Genoa, Palazzo Bianco |

Cigoli’s painting, on the other hand, which is in Florence ’s Palazzo Pitti, is both more suffering and more refined. Suffering can be seen in the face of Jesus, visibly overwhelmed by the torture he underwent. As in Caravaggio’s painting, he has the crown of thorns and the reed in his hands. Hands that are bound with a metal chain and not simply with a rope as in Michelangelo Merisi’s painting: this expedient also communicates more drama. Also distressed is the gaze of Pontius Pilate, who seems to participate in Christ’s pain. Cigoli’s refinement (he was Tuscan, thus more traditionally inclined to more elegant painting) is most noticeable in Pontius Pilate’s exotic attire: a damask tunic and a fashionable turban, all for an oriental-style outfit chosen, as Roberto Longhi had written, to “come better to meet the flowery and luxurious taste of the salient age.” The servant also appears in Cigoli, less young and with much less delicate features than Caravaggio’s.

|

| Cigoli’s Ecce Homo, Florence, Pitti Palace. |

By contrast, the painting executed by Passignano has unfortunately not come down to us. In the end, it seems that Cardinal Massimo Massimi decreed his decision: the winner of the competition would be Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli. And for quite some time many considered this tasty story, the story of Cigoli managing to beat Caravaggio in a competition, to be incontrovertible. But did things really turn out that way?

The passage we quoted at the beginning was written by Giambattista Cardi, Ludovico’s nephew, before 1628, thus a few years later than the painter’s death in 1613: it is a passage that has always conditioned the analysis of the two masterpieces. But are we sure of what Ludovico’s grandson wrote? Certainly, it would be very suggestive to think that there was indeed a competition between the three artists, and what is more, it was Cigoli who beat Caravaggio. A contest made even more fascinating today by the fact that, in the eyes of us contemporaries, Merisi’s genius appears far superior to that of Ludovico Cardi, despite the fact that at the time Cigoli and Caravaggio were both very established artists.

In the 20th century, however, the suspicion crept in that Giambattista Cardi’s step had been a ploy to celebrate the figure of his uncle and thus make it appear triumphant over that of one of the most in vogue painters in early 17th-century Rome and destined to condition the art of an entire century (and beyond). These suspicions turned into certainties following a study by art historian Rosanna Barbiellini Amidei(Della committenza Massimi in Caravaggio. New Reflections, a 1989 book in the series “Quaderni di Palazzo Venezia”). In her research, the scholar published documents testifying that there were two commissions, and separate ones at that. In fact, Caravaggio was commissioned to execute an Ecce Homo in 1605: the work was to be a pendant to a Coronation of Thorns made earlier. This is probably theCoronation of Thorns now preserved in Prato ’s Palazzo degli Alberti. There is a note from the Lombard painter, in which the artist himself writes that he undertakes to make “a painting of value and grandeur like the one ch’io gli fece già della Incoronazione di Crixto p[er] il primo di Agosto 1605.” The note is dated June 25, 1605. Cigoli, on the other hand, painted his Ecce Homo two years later, in 1607: there is a note left attesting to that date (to be exact, March three of that year). Two works therefore made on two different dates, two years apart (and the fact that Cigoli’s work was made later can perhaps explain the points of contact with Caravaggio’s) and in different contexts. And documents that have led scholars to discard the idea of a competition between artists and consider it a literary device by Giambattista Cardi. A “mere figment of imagination,” as Roberto Contini wrote in 1991 in his important essay on Ludovico Cardi.

So the documents bring us back to reality: but it is always romantic to think that these three great artists challenged each other in brush strokes, on the same subject, and that one of the three (and, moreover, not even the one who enjoyed the most success and esteem) turned out to be the winner. Reason why, although it has been ascertained that the competition did not take place, everyone still remembers this episode: invented, but suggestive. Of course, those who observe the painting will later be told that the competition never actually took place. But the episode continues to enrapture art lovers centuries later: even behind these anecdotes lies the fascination of art history.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.