It has only been discovered in recent years that Donatello ’s David (Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi; Florence, 1386 - 1466) once, when the bronze sculpture was kept in the Medici collections in their palace on Via Larga, today’s Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, had a base with an inscription that read “Victor est quisquis patriam tuetur. Frangis immanis Deus hopstis iras. En puer grandem domuit tiramnum. Vincite, cives!” meaning “Whoever defends the homeland is victor. The divine power shatters the enemy’s wrath. And a child tamed the great tyrant. Citizens, win!” The inscription, discovered in 1992 by scholar Christine Sperling, is later than the making of the statue and is attributed to Gentile de’ Becchi, a poet, clergyman, and tutor of Lorenzo de’ Medici who, in all likelihood, had intended to convey quite clearly, with that inscription of his, the values of civic patriotism that the David was to embody, the symbol of Florence, the symbol of the victorious people over their oppressors, and in all likelihood also an allusion to the pater patriae, Cosimo the Elder, who had been victorious over all his political opponents and had laid the groundwork for the rule over Florence to pass into the hands of the Medici, the beginning of the de facto lordship. In all likelihood, Donatello’s David dates precisely from the time when Cosimo the Elder, having returned from his exile in the Veneto region, had re-established himself in Florence in 1434, taking advantage of a power crisis and imposing his control over the city, while formally respecting civic freedoms.

However, we do not know exactly when the David was made, nor for what practical purpose (perhaps it adorned a fountain, and according to some it was part of a more complex allegory). Indeed, we are devoid of any document that can testify to the certain circumstances of the commission: almost a paradox, when one considers that the David is not only Donatello’s most famous work, but is also one of the few Renaissance sculptures capable of fixing itself in everyone’s imagination, one of the best-known works in the entire history of art. But is it not strange that of a work, even a famous one, we have not received documents that can certify beyond doubt its exact chronology, the name of the patron, its intended use. And even, one might say, the subject, for for a long time its identification with the biblical hero was anything but a foregone conclusion, since, on the surface, the iconographic attributes certainly do not suggest the Old Testament king of Israel. The sword, the petasus, the shoes, the obvious and exhibited nudity almost leave one to imagine, if it were not a work known to all, that Donatello wanted to depict the god Mercury cutting off the head of the giant Argos. Jenö Lányi, a young Hungarian historian who lived between 1902 and 1940 and author of numerous researches on Donatello, believed that both figures coexisted in the Florentine artist’s sculpture, an interpretation later followed also by Alessandro Parronchi who believed he read in Donatello’s statue a depiction of Mercury and Argos as an allegory of truth triumphing over envy. There would, however, also be elements that play against this identification: the sword is too large for an adult god like Mercury and is instead consistent with the figure of an adolescent such as David was when he defeated Goliath (the sword, of course, is Goliath’s), the shoes and petasus of the alleged Mercury are not winged (and the petasus, moreover, was not only attributed to the god of merchants: it was in fact a customary travel headgear in classical Greece, a wide-brimmed hat not uncommonly seen worn by shepherds and peasants, especially in ceramics), and Argos’ head would be missing something reminiscent of his most prominent feature, the hundred eyes that allowed him never to sleep. The discovery of the inscription adorning the base, however, has dispelled any doubts about the identification of the subject: there is no longer any reason, therefore, to believe that the subject is not the king of Israel. At most, one can wonder about the reasons for a rather unusual representation: it has been thought, for example, that the commissioners wanted to conceal their operation, we would say today, of cultural appropriation, since King David was part of the public imagination and the Medici could be accused of private use of a symbol that was supposed to belong to everyone, an accusation that would have been avoided by passing off the subject as the god protector of commerce, and thus an appropriate figure to be elevated to a family symbol (this

The nudity of the David, a nudity proper to an adolescent, an ephebic figure, should instead be read as a function of its placement, since the sculpture was imagined by Donatello to be placed on a tall column, a reason that explains why the David appears weak and puny to us if not viewed from the correct height. In fact, for a long time it was displayed a little more than a meter above the ground: a “museographic trap,” Francesco Caglioti called it, a trap that made the David lose “the effects of that ingenious anamorphosis that Donatello had put in place for the view from below.” The clue that perhaps most reveals the consequences of this error in the placement of the David is the petasus: if the sculpture is viewed frontally, the headdress overshadows the face, seeming almost recumbent. Things change, however, if one observes the statue from below, as it was imagined. And the nudity, then, gained meaning precisely by virtue of the positioning of Donatello’s bronze: “the Middle Ages,” Caglioti explains, "had feared and despised the nude in ancient heroic statues, always reimagining these champions of idolatry as gilded bronze, towering on columns. When Donatello first attempted the revival of the classical statue here, the combination of column, metal, and nude was a must, but redeemed now by the election of the noblest possible biblical character, progenitor and prototype of Christ, shepherd boy emblematic of Florentina libertas."

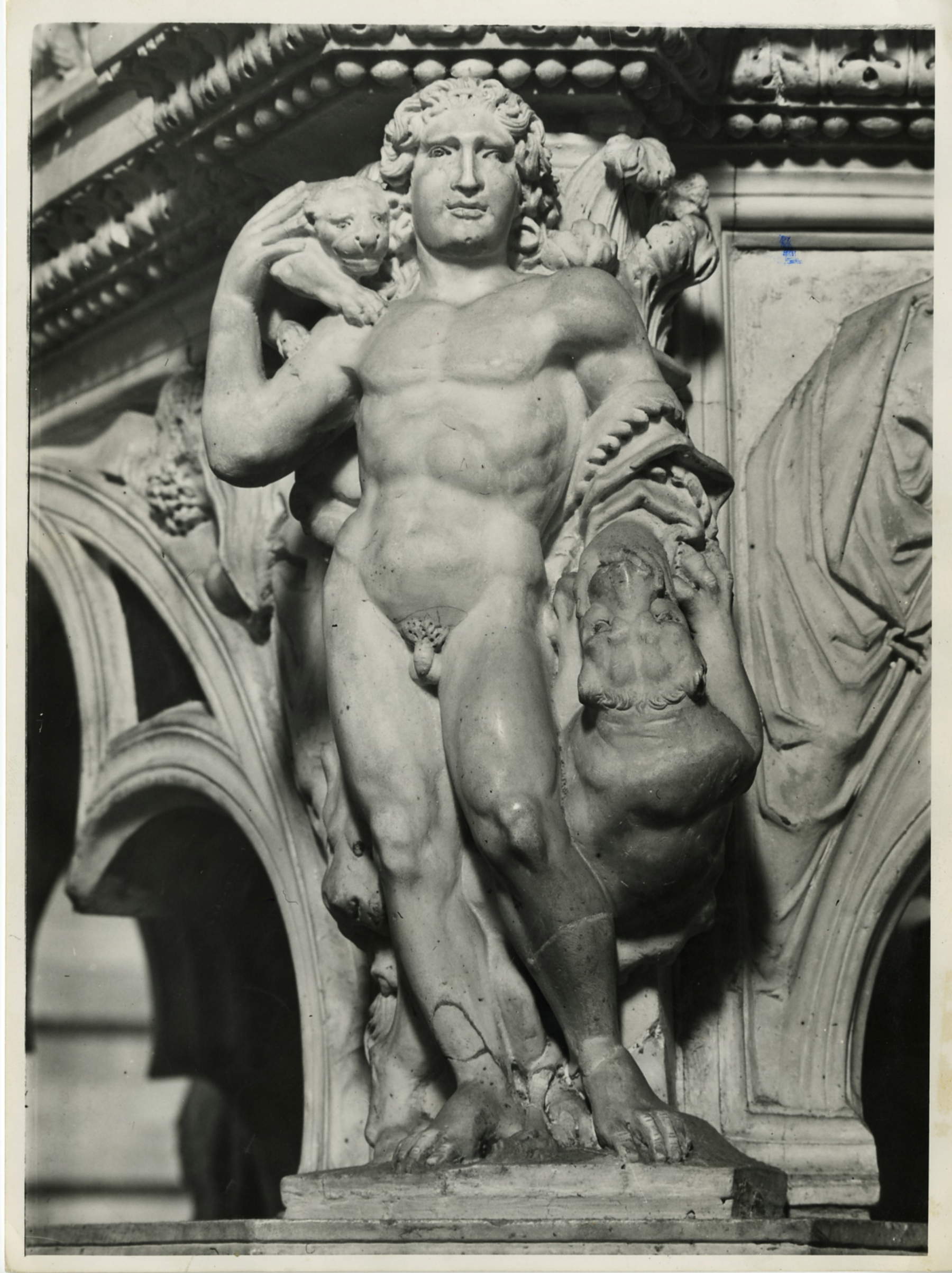

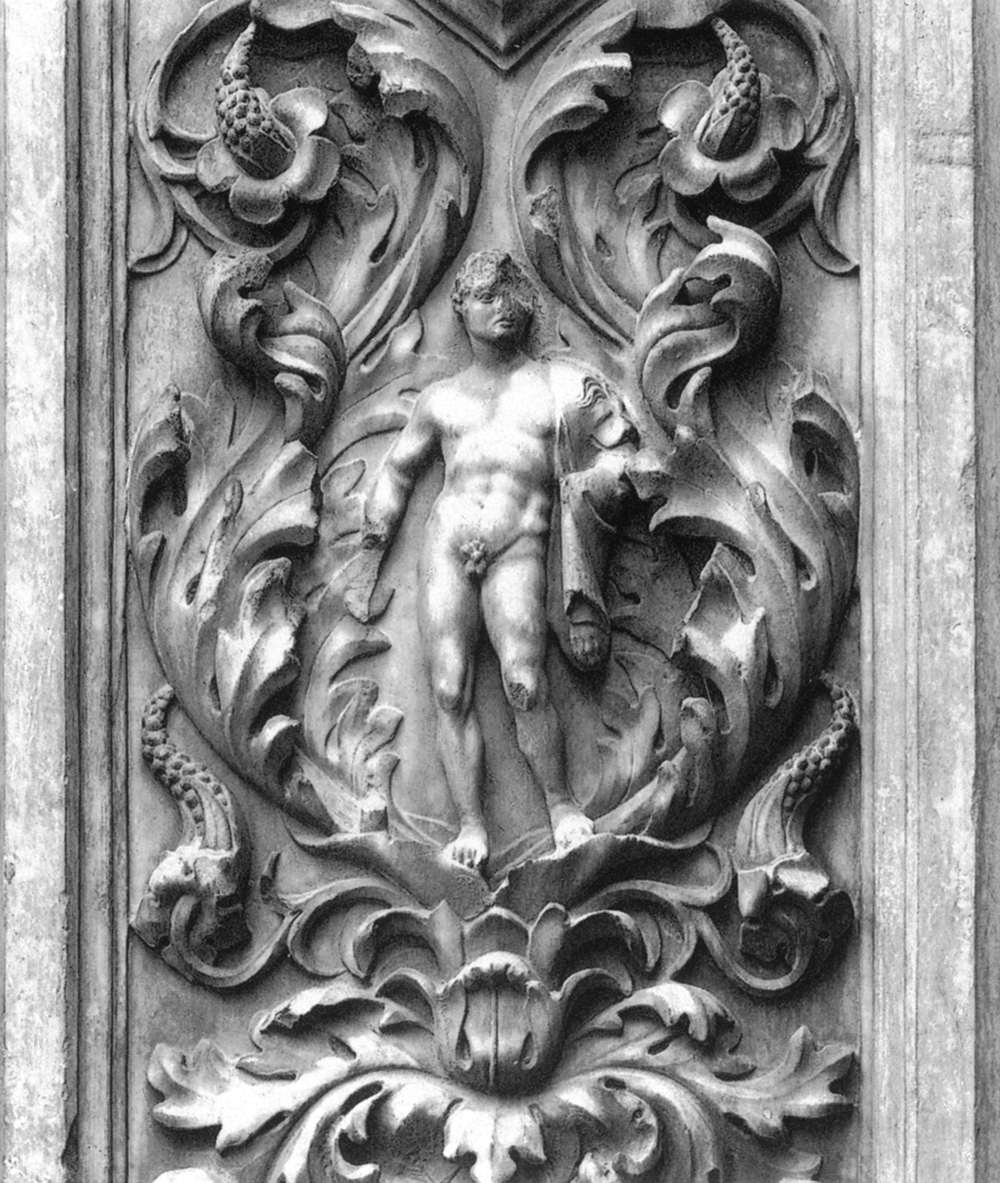

A David, then, who drew his inspiration from classical statuary: an inspiration that, therefore, made the unprecedented nudity necessary. The director of the entire operation was, in all probability, Cosimo the Elder himself, with whom Donatello agreed on the profound renewal of the iconography of the biblical hero, on which, however, the artist had already worked on at the beginning of the century, between 1408 and 1409, when the Opera del Duomo commissioned from him the marble David that is now in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, on a par with the later bronze David . The later David , however, is a work of disconcerting novelty, since it introduced an element of rupture, nudity found in classical statuary: before his bronze work, no naked David had ever been seen. Rather, David was usually depicted as the mature, bearded king of Israel, seated on his throne, although depictions of the young David intent on fighting Goliath had not been lacking, especially in the medieval miniature. At present, Donatello’s direct source is difficult to trace. It has been thought, however, that for the expression, he must perhaps have been aware of a face similar to that of the Antinous now in the Palazzo Altemps, and the same could perhaps be thought of for the physiognomy and pose, which resemble those of the Pius-Clementine Hermes. We do not know what Donatello had the opportunity to see, but surely, having been in Rome, he must have had the opportunity and time to reason about the classical sources that must have come to him in the Eternal City. Then there is a medieval precedent in Tuscany, Nicola Pisano’sHercules placed on the pulpit of the Pisa Baptistery, also sculpted in contraposto, with the leg resting more advanced than the one supporting the weight of the body, the knee bent and the body describing a slight S-shape (Nicola Pisano, like Donatello, had also made a full recovery of classical statuary, although compared to Donatello his was primarily a formal recovery). Another Hercules that perhaps Donatello could observe much better than Nicola Pisano’s was the one carved on the Porta della Mandorla in the Duomo of Santa Maria del Fiore. As for the overall impression, however, perhaps Donatello was well aware of the David that Taddeo Gaddi frescoed in the Baroncelli Chapel in Santa Croce in Florence: it is perhaps the most direct visual immediate of the David, as well as among the artist’s likely iconographic sources .

The bronze David in fact operated a recovery that went beyond what was seen. Already the idea of installing the sculpture on a tall column evoked what had been thought of in previous centuries for sculptures of pagan gods, an imagery that was nevertheless surpassed, incorporated into a form of syncretism that made Donatello’s and Cosimo il Vecchio’s ideas acceptable by virtue of the sacredness of the subject. Consequently, with the David, Donatello had achieved, Caglioti explains, “the first fully developed post-classical statue in 360°: but on the condition of bringing it back with the mind to its ancient summit, while the perception of it at about a meter from the ground (104 centimeters in recent decades) now makes one with it since the late eighteenth century, and invincibly belongs to the cultural baggage of the modern public, for whom this is the most authentic and most ’textbook’ Donatello.” The idea of a David that would also become a powerful civic symbol most likely had to manifest itself at the time the Medici moved into the palace on Via Larga. This was in 1457, and the new base, with Gentile de’ Becchi’s inscription, had been imagined with a view to placing the David in the center of the courtyard, so that even from the street the sculpture would be clearly visible (we know its placement from the first known source that speaks of the sculpture: a description, dated 1469, of the festivities in honor of the marriage between Lorenzo the Magnificent and Clarice Orsini). The David was shown alongside Judith, Donatello’s other, later bronze masterpiece (the heroine was executed between 1453 and 1457), whose fate has often been linked to that of the David. In charge of its marble base was Desiderio da Settignano (Settignano, c. 1430 - Florence, 1464), who was put in charge of the work since, beginning in 1459, Donatello had moved to Siena to work on the Duomo building site. Desiderio’s work has since been lost, although we infer its appearance from the description that Giorgio Vasari included in the Life of Desiderio himself: “He made in his youth the base of Donato’s David, which is in the palace of the Duke of Fiorenza, in which Desiderio made of marble some beautiful harpies et alcuni viticci di bronzo molto graziosi e bene intesi.” In 1494, when the Medici were driven out of Florence and the Florentine Republic was proclaimed, the David, like the Judith, was requisitioned and brought to the Palazzo Vecchio, along with its column, so that it could fulfill a new, lofty civic task. Then, sixty years later, with the Medici now firmly back at the helm of the city and having become lords no longer de facto but de jure, and then dukes and grand dukes, the David, it was 1555, was transferred to Palazzo Pitti, the mansion the sovereigns chose as their official residence (the Judith would remain in Palazzo Vecchio instead), and Desiderio’s base, like the column, went missing. The David, first placed on the facade, was later moved to the second courtyard and finally became a decorative element: it was placed on the fireplace of what we now know as the White Room. Instead, the entrance to the Uffizi and the new destination of the sculpture dates back to 1777: “museum-like,” we would say today, since the Vasarian complex had been chosen to house the vast grand ducal collection, and the David was placed in the hall of modern sculptures made with the arrangement imagined by Luigi Lanzi shortly after the gallery opened to the public in 1769. Eventually, it was moved to the Bargello, where today we admire it in the Salone di Donatello, on a 15th-century marble base, though no longer according to the perspective the sculptor had envisioned, no longer from the vantage point from which it would be proper to view the David.

The David had a disruptive impact on Florentine art of the time, since it was copied, imitated, taken as a reference model even by first-rate artists: it will suffice to recall, in a superficial roundup of the works that looked with good probability to Donatello’s masterpiece, Verrocchio’s David , Bartolomeo Bellano’s at the Metropolitan in New York, Antonio del Pollaiolo’sHercules at Rest , and then in painting the one that Ghirlandaio frescoed in the Sassetti chapel in Santa Trinita (and which in turn followed Verrocchio’s bronze), the one by Andrea del Castagno now in the National Gallery in Washington, and then again the David Martelli by Desiderio da Settignano, the David on panel painted by Antonio del Pollaiolo and now in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, all the way to Michelangelo’s David , which could not disregard Donatello’s precedent.

Critics have always tried to decipher this ambiguous figure. His ephebic nudity. The engorged petasus. The absorbed, melancholy gaze turned downward. The knee-length shoes. Goliath’s severed head wearing a singular winged helmet. These are all elements that have always ignited scholars’ fantasies, beyond the sculpture’s obvious political significance , which has been alluded to above. In the meantime, readings of a humanistic nature have been produced, with the David being interpreted as a reflection of the philosophy of the time: for Emma Spina Barelli, for example, the David is the symbol of the Christian humanist who is right with the ancient philosophers and would be explained, in her opinion, by the climate of Epicureanism that in Florence in the 1530s saw Antonio Beccadelli and Lorenzo Balla as its main points of reference. Then there are those who, on the contrary, have given a reading of the David in a neo-Platonist sense: Hans Kaufmann first, followed by Laurie Schneider and Francis Ames-Lewis, have identified the David as an allegory of heavenly love overcoming earthly love, and the nudity would therefore be an allegory of the hero’s inner purity. It is precisely the nudity that has provided the ground for disparate interpretations, for several reasons: it is unusual, not being present in the biblical text; it is ambiguous (from behind, the David may look like a woman); it could inspire a certain sensuality. So much so that Laurie Schneider herself proposed reading the nudity in a homoerotic key, an interpretation that was, however, rejected by later critics because of its anachronism (at the time, the concept of identity sexual identity was different from today’s categories, the idea of sexual identity as a fixed orientation did not exist), and, consequently, because of its character as a projection of a contemporary mentality onto a fifteenth-century sculpture. According to a well-known study by Adrian Randolph, the nudity of the David should be read according to the notion of “homosocial desire” formulated by scholar Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick: nudity should therefore stimulate a shared male desire (though not necessarily homosexual) while at the same time disciplining it. The work should therefore function as a means to invoke and at the same time nullify desire, instilling the idea of a control over desire that is both moral and social. Robert Williams has criticized this idea as being expressly “implausible,” because he assumes that both the artist and the commissioner should have shared this meaning attached to desire, and that they should have imagined some form of recognition from the public. Not to mention, then, that for fifteenth-century Florentines , beauty was not separate from religious significance: in other words, nudity was a sign of God’s grace rather than a kind of provocation or, at the very least, of This, however, does not mean that some erotic significance is not missing, albeit more subtle and more related to historical context: Williams, for example, pointed out that the epithet of desiderabilis that the sacred texts attribute to David may have justified his physical beauty, though irrelevant in the context of the struggle against Goliath, since it would be entirely appropriate in conveying the essence of the king of Israel. It is, in short, ideal rather than homosocial beauty .

Formal beauty then is a reflection of the profound symbolic and cultural significance embodied in the sculpture, witnessing a revival of classical ideals and a new focus on naturalism and human expressiveness at a time when Renaissance sculpture was being born. The David also inaugurated a new way of conceiving sculpture, which was no longer just architectural ornamentation, but became an expression of a way of understanding the beauty of a nude body and would later become a political symbol as well, assuming it was not already so (indeed, there are those who believe that from the very beginning the David represented Florence’s victory over the Visconti’s Milan). David’s bold and innovative nudity recalls the canons of Greco-Roman art, celebrating the beauty and perfection of the human body, while at the same time emphasizing the purity and youthfulness of the protagonist, traits that Donatello was able to render with surprising naturalness and delicacy. And ever since the David became a de facto public statue, Florence has always identified with the young biblical hero, a metaphor of moral strength that became a manifesto of Florentine civic identity.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.