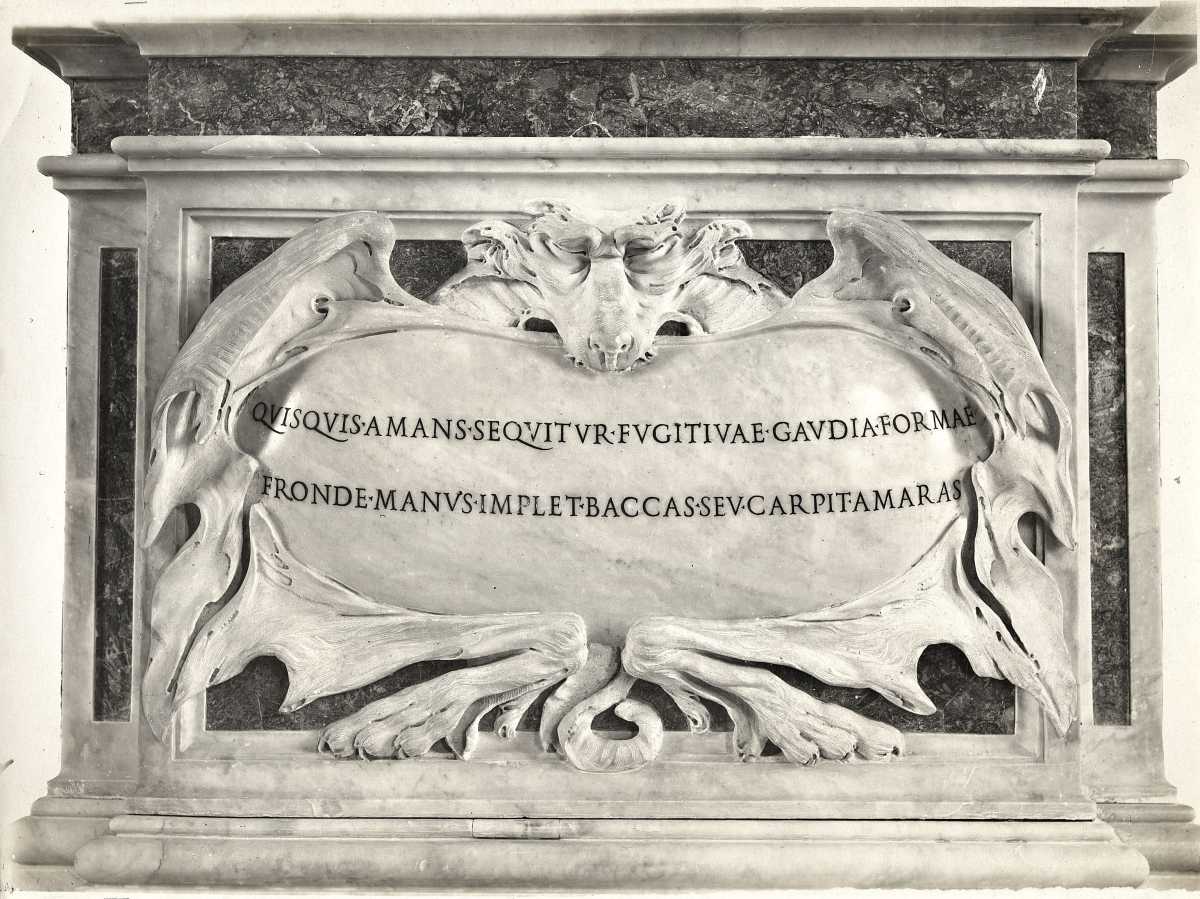

“He who loves and pursues the joys of fleeting beauty, fills his hand with foliage and plucks bitter berries.” This is the couplet that can be read at the base ofApollo and Daphne, the masterpiece by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (Naples, 1598 - Rome, 1680) preserved at the Galleria Borghese in Rome, in the center of the room named after the very famous sculptural group: composing the two verses in Latin (“Quisquis amans sequitur fugitivae gaudia formae / fronde manus implet baccas seu carpit amaras”) had been Maffeo Barberini, who was still a cardinal at the time Bernini began work on his work (he would ascend to the papal throne, with the name Urban VIII, on September 29, 1623): clear, then, is the initial moralizing intent of the work commissioned by Cardinal Scipione Caffarelli-Borghese, who turned in 1622 to the sculptor, then barely 24, to give form to the well-known pagan myth whose protagonists are Apollo, the god of the arts, and the nymph Daphne, daughter of the river god Peneus, caught in the final scene of the episode narrated by Ovid in his Metamorphoses. The Roman poet recounts that Apollo, after boasting to Cupid about the killing of the fearsome serpent Python, had to face the vengeance of the susceptible god of love, who prepared two arrows, one golden and one lead: the former made those struck by it fall in love, while the latter aroused a strong feeling of repulsion.

Cupid struck Apollo with the golden arrow, and Daphne with the lead one: the god, as soon as he saw Daphne, fell madly in love with her, and the nymph on the contrary rejected him. Apollo desired Daphne to such an extent that he set out after her to catch up with her and possess her, and she fled in fear: when it became clear that Daphne would be overwhelmed, the young woman, now in despair, begged her father, asking to be transformed to escape Apollo’s violent lusts. Peneus, in order to rescue his daughter, transformed her into a laurel plant: the god of the arts could only note the mutation, and from then on he decided that laurel would become the essence sacred to him, and with laurel leaves he would adorn his own foliage and that of poets and victors.

Bernini took three years to complete the Apollo and Daphne group, due to an interruption: in fact, he had to suspend work in 1623 when Cardinal Alessandro Peretti, who had just commissioned the David, a work that Scipione Caffarelli-Borghese asked him to finish for him, died: the sculptor’s energies were therefore absorbed by the David, completed in 1624. It was only in the autumn of 1625 that Bernini was able to finish theApollo and Daphne, thanks in part to the help of one of his most talented collaborators, Giuliano Finelli from Carrara. Instead, the payment for the base executed by Agostino Radi dates back to March of that year, the installation in the cardinal’s residence to August, and the final balance (one thousand scudi: keep in mind that at that time the average salary of a skilled worker was three scudi a month) to November. Three years to complete an immortal masterpiece that still fascinates us four centuries later, for so many reasons, and not only for the extraordinary technical virtuosity the artist was able to display.

It was not easy, meanwhile, to concentrate the episode in a single action. Bernini chooses a particularly concise moment (and also extremely difficult from a creative and technical point of view): the moment when Daphne’s transformation into a laurel tree has just begun but is not yet fully complete, so that we gradually see her legs and arms transform into a trunk and branches, and the fingers of her hands take on the appearance of leaves. Of extraordinary impact is the credibility with which Bernini describes the transformation, made all the more exciting by the strong sense of movement that the scene exudes: the artist captures the culmination of an agonizing race, still in progress, with the nymph perhaps not yet realizing that she is now safe, and so she surges forward , stretching her arms to the sky to get as far away as possible from the god blinded by his fierce desire induced by Cupid. He too is caught running, his left hand has now reached Daphne’s belly, his right arm, on the other hand, is fully extended backward to convey to the observer theidea that Apollo is still running (the god’s athletic legs, for that matter, are also in a running position), but the expression begins to betray a certain astonishment, one begins to read wonder in his eyes, before which the inescapable is being accomplished. And note then the fluttering of the loincloth that Apollo wears, swayed by the wind, just like Daphne’s hair : this effect, too, contributes to the action’s strong sense of dynamism that is immediately apparent when observing the sculpted scene. The effort is further emphasized by the tension in Apollo’s muscles and sinews, rendered with realistic rendering.

And then, right before our eyes, the miracle is unfolding: Daphne screams in dismay, but her beautiful body, entirely naked, has already begun to transform. We can no longer see her left foot, which is now blending in with the vegetation. The toes of her right foot are becoming roots. Her legs are taking the form of a trunk, which has already enveloped her entire left leg. And even part of her belly has become bark. And then the fingers of her hands are already branches from which fronds filled with laurel leaves are sprouting. It was precisely in these spectacular details that Giuliano Finelli’s hand was to be seen: the scholar Damian Dombrowski in fact decided to assign to him the most technically difficult parts of the group, namely the leaves, twigs, and roots, with the knowledge that the Carrarese artist, in works executed independently, often demonstrated daring virtuosity. Against this hypothesis, on the other hand, Kristina Hermann-Fiore sided, considering it difficult for an assistant to replace the master in the “bravura pieces,” also for reasons of image in regard to the client. Virtuosity is also appreciated in the way the marble imitates the texture of different materials: the softness of Daphne’s flesh, the lightness of leaves, the roughness of tree bark, the texture of Apollo’s tensed muscles. “The group,” observes Alessandro Angelini, “concludes an entire period of Bernini’s research around mythological-themed sculpture to which the artist would later not return, and represents a pinnacle in the sensitive rendering of pictorial effects achieved on marble.” To achieve these effects, Bernini resorted to the skillful use of the drill for the finest and most delicate parts, as well as for the hair, while for the less minute parts the artist employed, explained sculptor Peter Rockwell, “a ’wide variety of gradine, from the calcagnolo (a two-toothed step used for roughing out after the subbia) to a series of three- to five-toothed gradine, some with pointed teeth others flat, down to a relatively narrow two-toothed step used practically as a finishing tool. The purpose of this variety of gradine was to have the opportunity to explore shapes and features as it progressed inside the stone. Unlike the subbia, the gradine clarifies the forms enough so that we can see the figure rather than be visually attracted to the surface that has not yet been sketched.”

We can get an idea, from documents of the time, of how the sculptural group was installed, according to the precise instructions of Bernini himself: inside the third room (the one where theApollo and Daphne still stands today), placed near the wall bordering the chapel and the spiral staircase leading to the upper floor, so that the viewer could see Apollo’s right side, almost allowing him to follow him in his race to catch Daphne. Those entering from the chapel room would, in essence, see Apollo from behind. Although there is a privileged vantage point, compared to the other bourgeois groups, here one is allowed to observe the work, Angelini writes, “even from different angles, and to contemplate closely Daphne’s hair [...] or Apollo’s light drapery wrapping around her delicate limbs.” The left side of the sculpture thus remained toward the wall even though, Anna Coliva noted, there must have been a gap between wall and work such as to “grant the movement of the figures the natural space of expansion.” Probably, the scholar imagined, the placement was intended to make the figures proceed toward the center of the room so as to give more airiness to their expansion in space, also because the work privileges a moment in history that accentuates “themoment of stopping, thus of the completion of the action, the true narrative culmination, as opposed to the narrative of running, thus of waiting for a conclusion, which would instead be encouraged by the movement of the viewer’s eye through a true path to be taken along the generally indicated side.” So, perhaps, the work did not run entirely parallel to the wall: moreover, “the longitudinal axis oriented toward the center would also have allowed the sculptural group to be silhouetted in full luminosity, so that the perfect profiling dynamics could be admired, the slenderness of the material supports granted to the limbs, foliage, and hair, the virtuosity of the off-center, the free circulation of air between them, having the light and not the wall as a background.” The sculpture was later moved to the center of the room, thus to the position where we see it today, after 1785, when Marcantonio IV Borghese rearranged the collection of the splendid mansion as part of the architectural renovations entrusted to Antonio Asprucci and, following a suggestion by the sculptor Vincenzo Pacetti, had theApollo and Daphne placed in its present position. A drawing by Charles Percier from 1786, now in the Institute de France in Paris, documents the new and final arrangement of the room.

What iconographic sources could have inspired Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s inspiration? In the figure of Apollo, a reference has often been seen to theApollo of the Belvedere, the splendid marble statue, a Roman copy of a Greek bronze by Leocare, which was found at Anzio in the late fifteenth century, and which Bernini certainly knew: the languidness and delicacy of Bernini’s god are in fact precisely matched in the statue that can be admired today in the Vatican Museums. It has been noted how Bernini even replicated the shoes of the Belvedere Apollo, so closely did he hold on to the model of reference. For the figure of Daphne, on the other hand, it has been suggested that Bernini may have taken his cue from a modern work, Guido Reni’s Strage degli innocenti , and in particular from the face of the mother who flees screaming in the left part of the painting: the Bolognese artist had completed his painting in 1611.

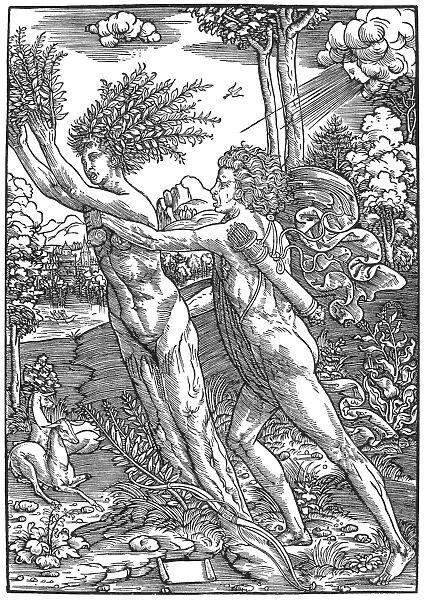

As for the running motif, a scene from the vault of the Galleria Farnese frescoed by Annibale Carracci, the one where Acis and Galatea are observed fleeing from Polyphemus who is hurling a boulder at them, has been indicated as a possible iconographic source: scholars have indeed been surprised by the correspondence between the figures of the two young lovers in Carracci’s fresco and Bernini’s, since the perspective from behind is very similar and the legs and arms are also placed in roughly the same position. Bernini was certainly familiar with the Farnese Gallery frescoes, not least because we know that he was an “admirer,” so to speak, of Annibale Carracci, and he perhaps drew inspiration from that detail so filled with pathos, despite the fact, Anna Coliva again noted, that Annibale Carracci’s world was “by then far removed from the research, from the spirit of the 1920s, in which the warm, triumphantly full-bodied classicism of the great master had already been elaborated, assimilated and then transformed.” Carracci’s frescoes were, however, a kind of iconographic mine for Bernini: even for the Rape of Proserpine , debts to the Bolognese artist’s work have been highlighted, and Rudolf Wittkower has well pointed out how the Tuscan sculptor had taken to looking atclassical antiquity precisely through Carracci’s eyes, subordinating his observation of reality and his gaze on ancient art to Carracci’s interpretation. And again for the moment of the race, another painting by Guido Reni, theAtalanta e Ippomene, could perhaps provide some inspiration, especially for the impression of movement that Bernini was able to give to the scene and that in certain elements (for example, Apollo’s fluttering drapery, or Daphne’s hair) recalls the Reni painting. Even the idea of the veil starting from the god’s arm, describing an arc, and then winding around his pelvis could derive from Guido Reni’s painting: see how Apollo’s drapery follows in a very similar way the course of Atalanta’s veil as she bends to pick up the apples thrown by Hippomenes. And again, Irving Lavin has pointed out a possible relationship with theAlphaeus and Arethusa executed by Florentine sculptor Battista Lorenzi for the Villa del Bandino (now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York). There is also an engraving by Cherubino Alberti, derived from a work by Polidoro da Caravaggio, which may have provided further insights, especially in the way the draperies are depicted. Another engraving, by the “IB Master,” captures instead Daphne as Bernini represents her: with her legs already changed into a trunk and her arms becoming branches with leaves.

The contribution of literary sources should also not be underestimated. In fact, several scholars have related Bernini’s group to the poetry of Giambattista Marino (even more than to that of Ovid), not least because the distinct pictorialism of the scene sculpted by Bernini seems almost a translation in images of the sonnet on the Transformation of Daphne into laurel, published in 1620, thus just two years before Bernini began sculpting his group: “Tired, yearning for the paternal shore, / quale suol cervetta fatigued in caccia, / ran weeping and with lost face / la vergine ritrosa e fuggitiva. // And already the ignited God who followed her, / reached by now of her course had the track, / when stopping the plants, raising her arms / rudely he saw her, in that which she fled. // He saw the beautiful root foot, and saw (ouch fate!) / that rough bark the vague members hides, / and the green shadow of the aurata mane. // Then he embraces and kisses her, and, of the blond / frieze novel hairs, from the beloved trunk / at least, if’l fruit no, he catches the fronds.”

Enthusiastic was the reception given in the seventeenth century to Bernini’s sculptural group. One finds the first known mention in literature of theApollo and Daphne in Giacomo Manilli’s 1650 description of Villa Borghese, where he speaks, admittedly rather aseptically and without judgment, of a “large group of Daphne, followed by Apollo, which begins to change into laurel, the work of Cavaliere Bernini.” Before that, however, it is letters that preserve traces of the group’s reception: a missive from the man of letters Lelio Guidiccioni, addressed to Bernini himself, dates back to June 4, 1633, in which some of the groups, including theApollo and Daphne, are described as “excellent statues” that “are held in supreme esteem.” In contrast, a positive comment by English traveler John Evelyn, who in a diary speaks of the “new work of the Apollo and Daphne by Cavaliero [sic] Bernini,” described as a sculpture that “is admired for its pure whiteness and for the art of statuary, which is stupendous,” dates from 1644. Another traveler who left a record ofApollo and Daphne is Paul Fréart de Chantelou, who accompanied Bernini as a translator during a visit by the artist to France, and in 1665 wrote a diary that also contained several tidbits of information about the Bourgeois group. In the diary, Chantelou attributes a very particular reaction to the French cardinal De Sourdis, who is said to have remarked to Maffeo Barberini that, if the work had been in his house, he would have had some scruples about showing it, since the nudity of a beautiful girl might have disturbed the spirits of those who would have seen it. In 1682 it was the turn of Filippo Baldinucci, author of the Vita del cavaliere Gio. Lorenzo Bernino scultore, who spoke of it in enthusiastic terms: “To want me here to describe the marvels which in every part of it uncovers to the eyes of every one this great work, would be to toil much and then conclude nothing.”

However, critics were not always benevolent toward Bernini: the approval of contemporaries was followed, in the 18th century, by a period of rejection, silence, and essentially negative judgments, when not critiques, even ofApollo and Daphne: for example, in the diary of the Spanish playwright Leandro de Moratín’s travels in Europe, the Bourgeois group is judged cold and soulless. Not of the same opinion, however, was Antonio Canova, who in his diary, dated March 11, 1780, following a visit to Villa Borghese, thus wrote: “I then saw the group of Apolo and Daphne by Bernini worked with such delicacy that it seems impossible, there are the laurel leaves of marvelous work, beautiful still is the nude that I did not believe so much.” Soon after, in 1796, in Luigi Lamberti and Ennio Quirino Visconti’s Sculptures of the Villa Borghese palace , we read again a very positive description: the Apollo and Daphne group is described as “one of the most distinguished monuments of ’Modern Art,’” and no praise is spared for Bernini, despite the excitement that, in the midst of neoclassical culture, was seen as a flaw (“The fineness of the work executed to perfection in the utmost difficulty of the undercuts, and in the subtlety of the leaves, branches, and drapery, the softness of the flesh, the truth, and the exquisite imitation of all the accessories, and the grace of the expression though excited are indisputable merits of this excellent group.”

The witness of the negative critics was later picked up in the twentieth century by Howard Hibbard, who in his 1965 monograph on Bernini accused him of having been excessive because of his young age, and thus of having produced a work far from perfection, of having displayed virtuosity as an end in itself. In general, however, the judgments of contemporary critics are mostly positive: for Irving Lavin, for example,Apollo and Daphne is the sculpture that best exemplifies the meaning of classical art for Bernini, as well as a work that well represents his originality (“Bernini’s main concern,”, Lavin wrote, “was to present the viewer with a dramatic momentary situation, and we know from documents that the artist took care to arrange the group against a wall, so that it could only be seen from one side. By concentrating the action of the figures, Bernini transformed the entire course of European sculpture.”). In the opinion of Andrea Bolland, who describedApollo and Daphne in terms of a work that also speaks to the relationship between sculpture and poetry, the group “thematizes the conditions of illusion itself: what you see is not what you get (and if Apollo’s face registers his wonder at the distance between what he sees and what he feels, that wonder is an equally appropriate response to Bernini’s artifice). Bernini here gives a demonstration that sculpture can have the same claims to be a convincing fiction as painting: the distance between hard marble and the reality of flesh is as great as (if not greater than) that between the table and the three-dimensional world.” Again, for Maria Grazia Bernardini, with this work Bernini, more simply, “breaks every link with previous art and formulates a new language, which we could already define as fully Baroque,” and “reaches one of the peaks of art of all time.” Peter Rockwell wrote that "any sculptor who looks at Bernini’sApollo and Daphne cannot but come away amazed." It is an opinion shared by thousands of people who today flock to the rooms of the Borghese Gallery often with the specific intention of admiring Bernini’s groups, and to be amazed by his mastery and that grand Baroque theater that, with theApollo and Daphne, sees its beginnings.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.