He was a painter from Lombardy, Giorgio Belloni: born in Codogno, studied at the Brera Academy following Giuseppe Bertini and admiring Filippo Carcano, an early part of his career spent between Milan and the Veneto. How much further one could imagine from the sea: yet, few others knew how to interpret the breath of the sea as well as Giorgio Belloni. To his contemporaries, he was the “painter of seascapes.” A serious, calm, modest painter, his life was totally far from the excesses and clichés that are usually attached to artists. A happy disposition of his soul, meditative and melancholy, and a masterful technique, exercised in the many landscape views, notably of the mountain villages of Canton Ticino and Valtellina that had punctuated the early part of his career, had led him to become the most lyrical poet of the sea in the early twentieth century. Calm sea expanses, choppy waters, boats sailing toward the horizon at sunset, fishing villages and ports of smoking chimneys, a few crowded beaches, winter solitudes on the shores: Belloni’s output is a continuous ode, passionate and loving, woven in praise of the sea.

Una mareggiata is among his best-known and most important masterpieces. It is called just that: Mareggiata. Giuseppe Ricci Oddi, the incomparable, ardent and shy collector who in 1931 donated his collection to his native Piacenza without asking for anything in return, had purchased Giorgio Belloni’s work in 1911, through his trusted friend Carlo Pennaroli, a man of “fine taste” and “steadfast and keen attention,” a bank accountant with a boundless love for art, and Ricci Oddi’s invaluable prompter. The transaction took place on March 18 of that year, the agreed cost for the Mareggiata was not much: 1,100 liras. That would be just over four thousand euros in 2022. Among Giuseppe Ricci Oddi’s notes, there are a few words reserved for the purchase of the painting, annotated with Marina’s name: “Together with my friend Pennaroli I went to visit the studio of this good painter, who welcomed us with great affability. He then the following year honors me with a visit from him.” Today, in the splendid, bright and modern building on Via San Siro designed by Giulio Ulisse Arata, Belloni’s Mareggiata is arranged in Room IX, that of the Lombard artists.

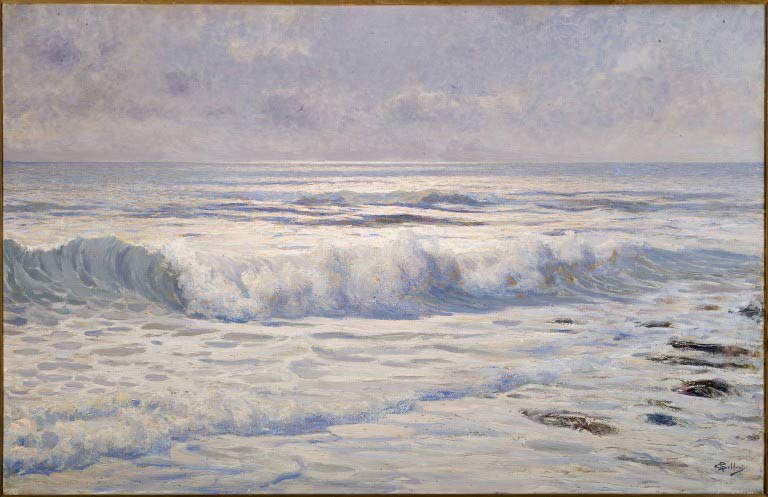

Belloni, a fine and sensitive painter, makes us imagine a stormy sea day, taking us among the billows that shake the waters of the Ligurian Sea, in front of one of the many swells he must have seen during his repeated stays in Sturla, Noli, and Forte dei Marmi. To the relative who immerses himself in the Lombard’s picture, favored by the medium format, he seems to hear the lapping of the waves. The foam hides almost the entire surface of the water, enveloping the rocks that emerge near the right edge of the canvas. A few muted patches in silvery tones emerge, here and there, where the foam already fades. Toward the horizon the sunlight sparkles on the water: the thick, gray clouds do not arrest the glare of the sun’s rays; a splash of pearly luster spreads offshore, where the sea is calmer. Even on a stormy day, the sun’s glow comes and comforts, promises the imminent approach of serenity.

Now, however, the sea is rough. Halfway through, here is a wave: in the center it has already closed in, we imagine it swift and roaring toward the shore, pushed and reinforced by the wind, amid splashing spray in its incessant rush. On the left we see the ridge on the verge of breaking, we glimpse the “cima leggiera” that “s’arruffa come mane nivea di cavallo.” Who knows if Belloni ever read D’Annunzio’sAlcyone and the unparalleled verses of L’Onda, finding some inspiration to paint the “free and beautiful” wave, “a living creature enjoying its fleeting mystery.” We do not know. We do know, however, that if one wants to speak of assonances, one must stop only at the surface, at the lapping of the waves, at the ripples that move the sea: The wave of the Vate is a complex image, full of metaphors and mindful of ancient Greek myths; Belloni’s Mareggiata is, on the contrary, pure poetry of simplicity.

However, there are those who have thought to find symbolic meanings in this marina by Giorgio Belloni. We do not know the artist’s intentions: probably his intent was simply to restore on canvas the poetry of the sea troubled by the wind. Belloni was a realist artist, thus little inclined to see in the waves a mirror of his soul. And yet only an artist capable of being moved before the waves could be able to raise to the sea a song so alive, so poignant, so loving. There may be no correspondence between the agitated waters of the sea expanse and the painter’s sentiment, but it is evident that, behind this Mareggiata, there is at least a burning desire and a soul that is inflamed before nature. Enrico Piceni, the great collector and art critic who published a monograph on Giorgio Belloni in 1980, could not fail to observe that his sojourns in Liguria were motivated by the need to find “the atmosphere best suited to express his own aspiration for light.” A light that, moreover, was not interested in what the avant-garde had been saying for some time. In the last decade of the nineteenth century, the period to which the Mareggiata most likely dates (but it is not certain that it was not painted later), the last Impressionists were continuing their experiments on the synthesis of atmospheric effects, and Divisionist poetics had established itself with its research on light and color. When Ricci Oddi bought the painting, in 1911, the Futurists had already been lighting up Italy for two years with their incendiary manifestos, and Marinetti, in that same year, was verbing his intention to kill moonlight. But for Belloni, painting meant first and foremost offering the bystander the image of nature.

And so his light tends to capture, Piceni writes, the emotions aroused in him by the vision of the sea, “precisely in function of a conversation with nature that would find in the latter not only the inspiration but also the purpose of the depiction.” There is no suggestion, however, that Belloni was a passatist, a nostalgic laggard, used to wearily repeating a painting that was. The novelty of his language is expressed in his attempt to update realist painting with the effects of light and atmosphere that he had evidently observed in the works of the Impressionists and Divisionists. He is not a symbolist, although it may seem so: the symbol, wrote Rio di Valverde in 1921, a pseudonym by which the journalist Vittorio Giglio signed himself, “he draws it from the very sense of things and from the vibrations of feeling that they arouse.” The result is images of a more vivid immediacy, realistic views that are illuminated by unprecedented intonations, devoid of the hidden enigmas of the Symbolist painters (although Belloni does not lack the ability to capture the essence of things), far from the tensions of autonomy manifested by the Divisionists, but which nonetheless are cloaked in lyrical accents, suggested by the sensitivity of a man who felt beauty. Gleams, reflections, flashes of light, seas of mother-of-pearl, dances of clouds under iridescent skies. In this desire to explore the infinite forms of water lies the beauty and originality of Giorgio Belloni’s sea, verist with the soul of a poet.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.