Giovanni Fattori’s drawing, wrote Barna Occhini in 1940, in an article in Frontispiece, “is the most expressive that can be given, but the most reluctant to express itself in words.” Occhini, in fact, immediately disregarded his catch-phrase, since he immediately captured, in exact words, the whole precise essence of Fattori’s drawing: “it is the simplest and the most problematic, the most obvious and the most enigmatic. It adheres frankly to the images, reproducing them like a photograph just a little moved, and sometimes a little veiled; but it has the energy of a chiseling. It keeps identical in value, to the good moments, both in the minimal and the major pictures.” The Aretine journalist had paintings in mind when he spoke of Fattori’s drawing, but the same qualities also emerge, and perhaps even more forcefully, when one looks at his sheets, the studies for his paintings. The recent Piacenza exhibition (at the XNL Center for Contemporary Art in Piacenza, March 29 to June 29, 2025) had the merit of bringing to the public’s attention a large body of Giovanni Fattori’s drawings preserved at the Istituto Centrale per la Grafica in Rome. A valuable nucleus, since it is capable of documenting different phases of Fattori’s career, and also because it is rarely exhibited, despite being part of the Institute’s collection for more than a century.

It was in 1911 when the director of what was then called the Gabinetto Nazionale delle Stampe, Federico Hermanin de Reichenfeld, decided to acquire a significant representation of Fattori’s graphic works, who had recently died (in Florence, in 1908) after a career of mixed fortunes (starting with the economic ones that did not always come his way). Hermanin, writing to Education Minister Credaro on October 11, 1911 to advocate the purchase, had described that operation as an “opportunity,” a relevant opportunity it would be added, for the possibility of being able to enrich the collections of the then Cabinet with “an important group of etchings and drawings by Giovanni Fattori,” he wrote, “the spirited and outspoken artist who was among the first in Tuscany to take up the cry of revolt that against academic and official Italian art raised, returning from the Paris Exhibition of 1899, Domenico Morelli, Saverio Altamura and Serafino De Tivoli.” Hermanin also emphasized the favorable terms of purchasing the entire lot, consisting of twenty-six drawings and thirty-six etchings (3,210 lire, or about 15 thousand euros today, effectively very favorable terms: with today’s market quotations, it would take at least twice as much to buy a comparable lot). A congruous sum to grab a group of sheets that “give, in their sober technique and frank and rough sign, a complete vision of the sincere and powerful art of this painter, who felt and illustrated in a wholly personal way the rough and sad work of the Maremma, the rush of battle and the dark labors of the soldiers of the fatherland.” However, the sheets purchased by Hermanin in 1911 would not be exhibited and published for the first time until 1969.

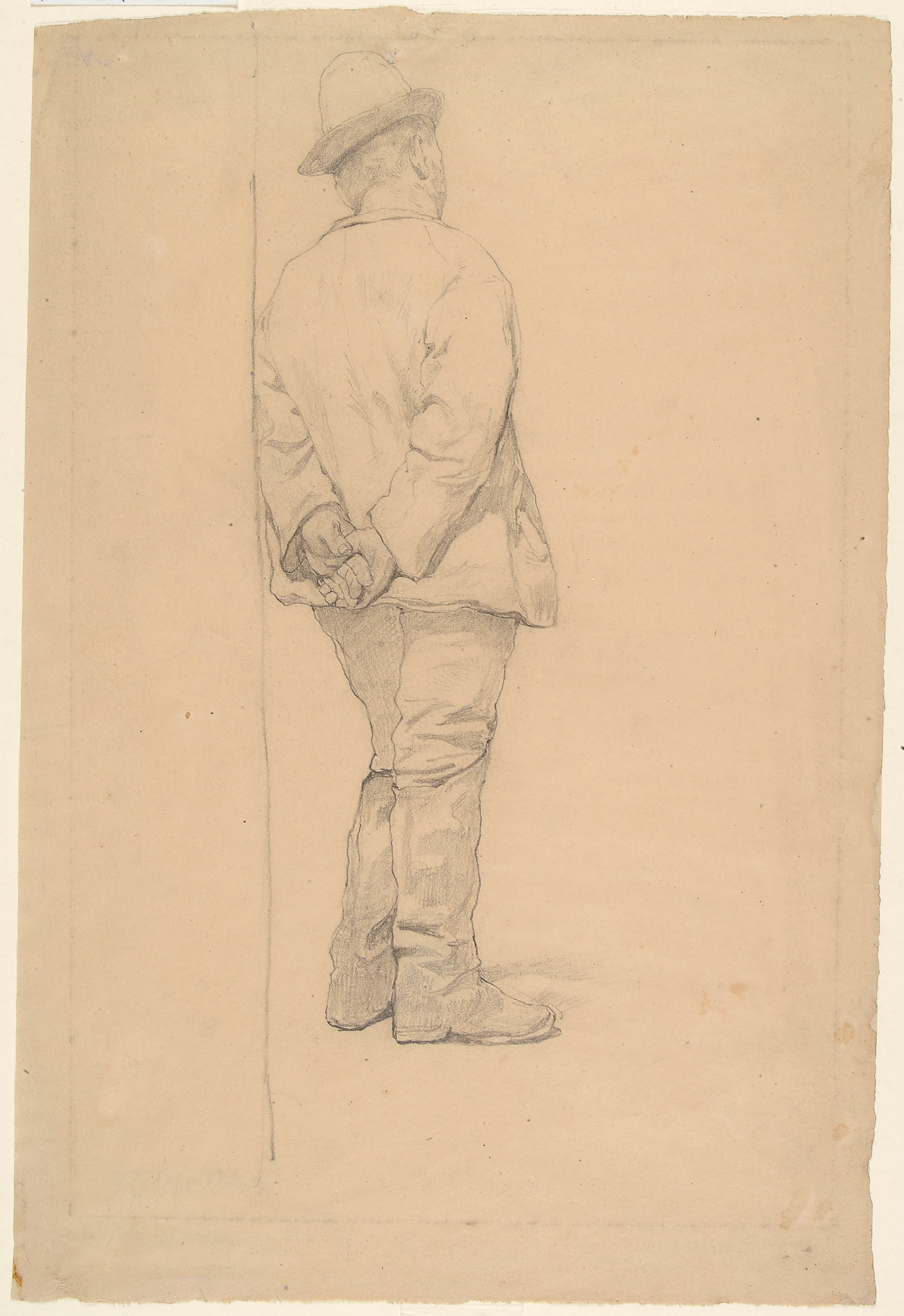

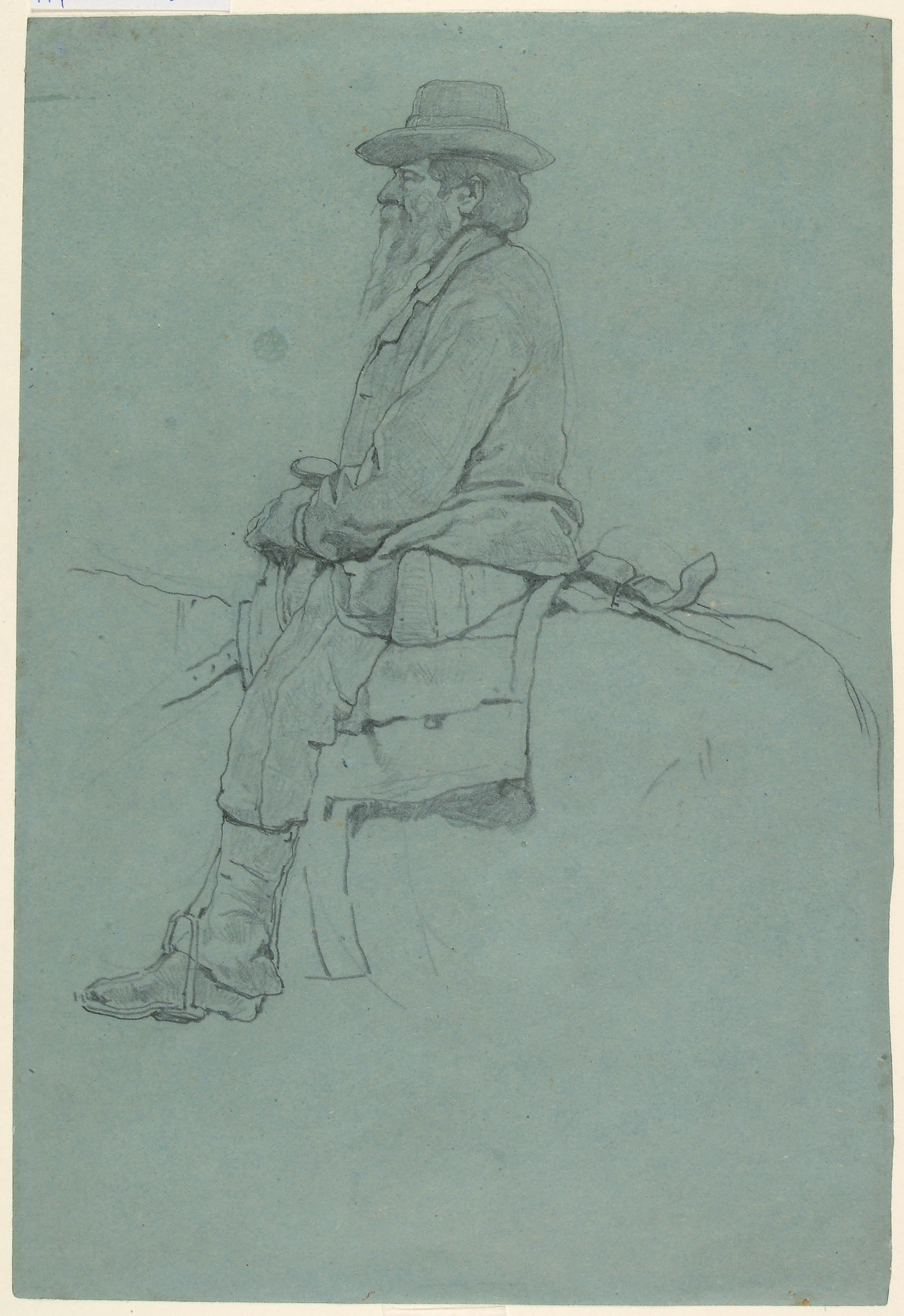

The nucleus includes preparatory drawings for paintings, or proofs for compositions, or studies for elements of larger compositions, moving on to perhaps the most interesting drawings, that is, everything Fattori captured from life: also part of the nucleus at the Central Institute for Graphics is an early notebook, dating from shortly after 1860, which entered the institution’s collections in 1971 and was published in 2007. It is one of the many notebooks that Fattori bequeathed to his pupils Giovanni Malesci and Carlo Raffaelli (the one in Rome comes from the Malesci inheritance: it bears the well-known embossed stamp of Fattori’s works bequeathed to Malesci himself). The notebook takes account of some of Fattori’s outings in the Maremma, where he was able to fix on these little notebooks mainly landscapes, soldiers, figures of peasants. “These are happy annotations,” wrote Fabio Fiorani, “brief poetic hints that illustrate aspects of daily life lived with extraordinary toil, existences repaid only by continuous and exhausting labor, but always captured in their absolute dignity.”

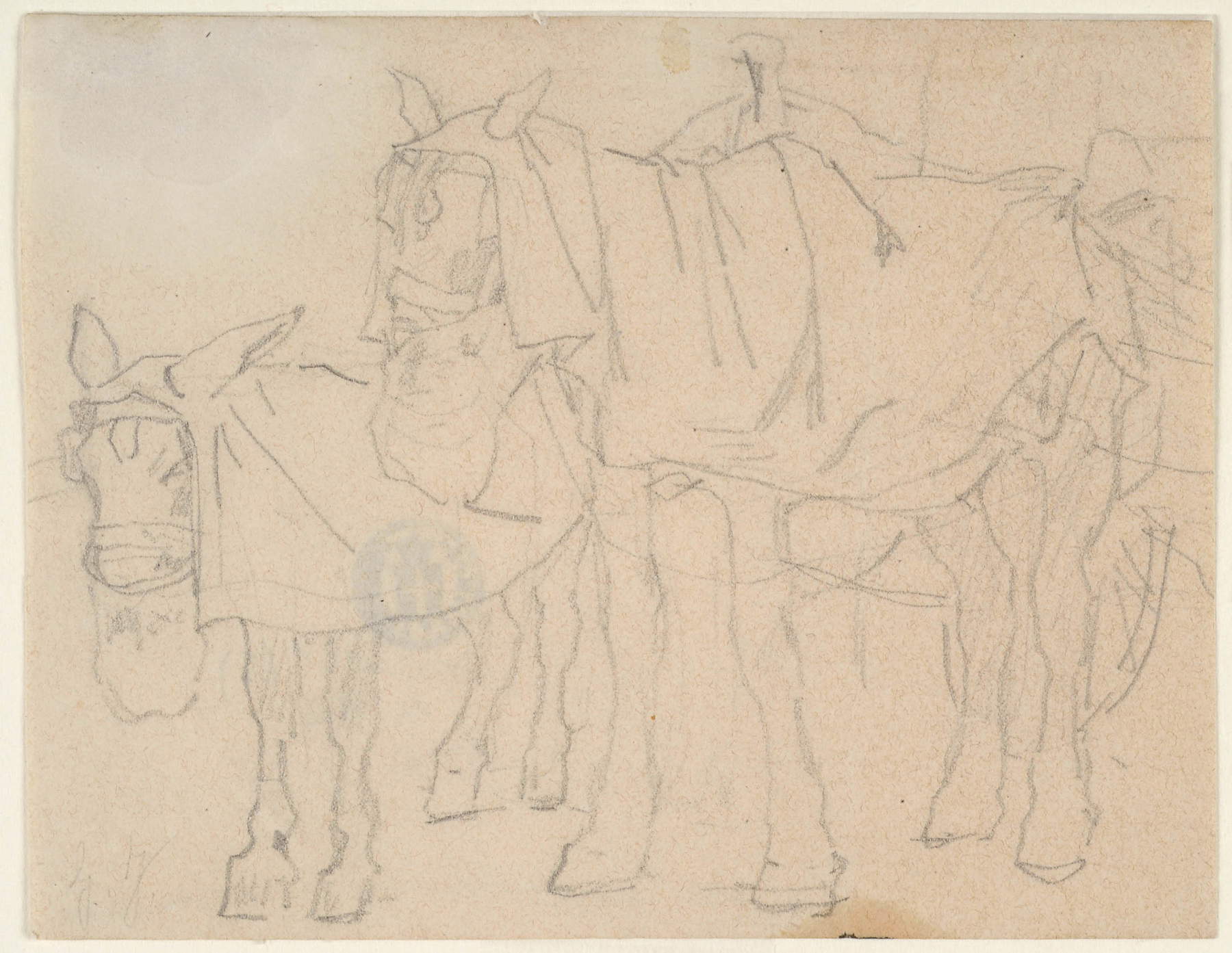

One appreciates, in Fattori’s sheets, the marked differences between the different types of drawing. The studies for the compositions are sketches that do not linger on the details and are intended above all to imagine the placement of elements, figures and groups within the scene: it is not uncommon to find figures outlined with double hatches, repainted with Indian ink or pen, corrected as if to experiment with minimal but fundamental variations. In some scenes, especially battle scenes where soldiers and cavalrymen are sketchily sketched, one can easily see, through the marks left by Fattori in the early stages, even the visual guidelines that organize the composition, which is often almost set on geometric constructions (one can see well, for example, in the sheet with inventory number D-FN748, a Study for a cavalry charge).

On the other hand, the views of landscapes studied from life are rapid but sure, outlined with a few pencil strokes, but nevertheless always animated by a marked sense of depth, obtained even with very simple means by the sole means of perspective (admirable in this sense is the Veduta con ponte on sheet D-FN3982: it is also from these drawings that one admires all of Giovanni Fattori’s experience, that one appreciates the artist’s mastery of technical means). Finally, there are the studies of elements to be incorporated into larger compositions, such as the Trumpeter on sheet D-FN316, or the peasant who would later end up in the 1894 painting Love in the Fields , now in a private collection. These are the most elaborate drawings, the ones through which Giovanni Fattori also studies details (the folds of clothing, parts of the body, or the shading that is sometimes achieved, as artists did in ancient times, with more or less intricate networks of crossed vertical and horizontal marks according to the amount of shadow needed, sometimes simply by blurring the pencil strokes, or making them thicker and denser). We imagine them executed in the artist’s studio, but born from impressions pinned down from life. They are also the drawings that the public usually appreciates the most, because they are the least “technical,” if that adjective can be used, the most elaborate, the ones closest to the painting, the least difficult, and consequently also the most self-contained.

However, a characteristic that remains common to all of Fattori’s drawings, throughout his career, is that dryness that makes them so simple, so dry but at the same time so sincere and that, Occhini said again, marked a distance between Fattori and the greats in the history of art’art that had preceded him, who were endowed with a “dripping, juicy force that spreads out in replicated dashes of curves,” a force to which Fattori opposes a drawing that is “straightforward, upright, true but without bluntness of softness.” It is, in essence, pure drawing, a drawing that has the force of writing, that almost allows one to enter the mind of Giovanni Fattori, to follow his creative process, to accompany the artist during his walks in Maremma, on the Leghorn coast, on the streets of Florence, in those places where the wonder of theartist was constant (“All the creation that I see I observe and touch enchants me, makes me think, and it is of no use either to understand or to define,” Fattori wrote) and thus allowed him to find interesting and fascinating even the most seemingly mundane everyday life, the one we tend not to pay attention to. It was Fattori himself, in an autobiographical note in 1904, who explained his way of working. The paintings he made between the 1950s and 1960s, which were capable of enjoying some success (Fattori himself gave the example of theAttack on the Madonna of Discovery), the artist recounted, had given him “the burning stimulus to make studies of animals and landscapes, to be continually an observer of military life. And this assiduity obliged me to observe everything, and I was always interested even as I could in putting on canvas the physical, and moral, sufferings of everything that unfortunate happens. Thinking that [I couldn’t] just observe without taking notes and then I got a small album and there I marked, and I mark everything I see. More, it was a real means of making horses, and other animals by finding them and studying them on the street without dealing with the demands of aesthetics-which wants them all beautiful-or beautiful, or ugly. It is the form that one must know, and in my little albums one will find horse noses, hooves, legs, whole, etc., made on the street hiding in the doorways, and where I could hide.”

Scholar Giorgio Marini draws attention to the changes in Fattori’s drawings after 1870, when “the stroke departed from the firm clarity and geometrizing progression of the early days, becoming more elaborate in the shadows and chiaroscuro, in an increasingly pronounced search for autonomy that would result in the great adventure of the etchings, decanting the angular and unbreakable sign of the drawings into the almost material, violent and acid-browned sign of the etchings.” Fattori would begin to practice etching from the mature stage of his career (and still can be considered one of the greatest etchers ever: the Fattorian etching is a completely autonomous art with respect to painting, and if today it is possible to consider it as such it is also thanks to the efforts of Andrea Baboni, one of the greatest experts on Giovanni Fattori, who has long studied this portion, often in the past neglected, of the Leghorn artist’s production) and between the drawings from the 1870s onwards and the etchings it often happens to find a “conceptual continuity,” Marini writes, “between motifs fixed on the drawings that are later found in his prints, directly relating the free activity of daily annotation to the subsequent transposition on the plate”, as is evident by comparing the Study of Dog and Horse (D-FN11105), a quick sketch from life, with the etching Goodness and Sincerity, but the examples could go on and on.

Drawing is the most immediate means for an artist to translate an idea into an image, and it is also for this reason that drawing is so fascinating, although sections on drawings at exhibitions are often neglected (the Piacenza exhibition that displayed the core of drawings from theIstituto Centrale della Grafica nevertheless decided, with supreme intelligence, to display them at the opening of the exhibition itinerary, so as to show them immediately when the concentration of the public is at its highest). And for Fattori, scholar Giovanna Pace has rightly observed, drawing was “a means of capturing the essence of reality,” which is why each of his sheets becomes “a small story, a fragment of reality that the artist knew how to transform into visual poetry.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.