In his Lives of painters, sculptors and architects, the painter Giovanni Baglione, in the chapter devoted to the Florentine artist Jacopo Zucchi (Florence, c. 1541 - Rome, 1596) recalls the latter’s collaboration with Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici (Florence, 1549 - 1609), who was initiated from a very young age to an ecclesiastical career (he received the purple when he was only thirteen) but was destined to become Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1587, after the death of his brother, Francesco I. Baglione writes, speaking of Zucchi: “He came to Rome as a young man in the Pontificate of Gregory XIII, and nhebbe protettione Ferdinando de Medici allhora Cardinal; tennelo in casa, and many things he had them paint, and among the others a studiolo, which is in the palagio of the de Medici garden, representing a coral peach with many naked Women, but small, among whom are many portraits of various Roman Ladies of those times very beautiful and worthy as of sight, so of marvel.” The work to which Baglione refers adorned in ancient times the cabinet (“studiolo”) of Ferdinando de’ Medici in his Roman residence, Palazzo Firenze, now the headquarters of the Dante Alighieri Society: four versions of the painting are known, but the one of the highest quality, as well as the one that was most likely originally in Palazzo Firenze, is the one now preserved at the Galleria Borghese in Rome. The others are in the “Borys Voznytsky” National Gallery in Lviv in Ukraine and in two private collections, one in Milan and one in Russia. The painting is known as The Coral Fishery, as Baglione noted. Actually, the title is insufficient to describe the painting, since coral fishing is not the only activity to which the protagonists of the work are engaged. Others were therefore proposed: The Treasures of the Sea, The Discovery of America, and The Reign of Amphitrite, with the latter, coined by art historian Philippe Morel, prevailing over the others.

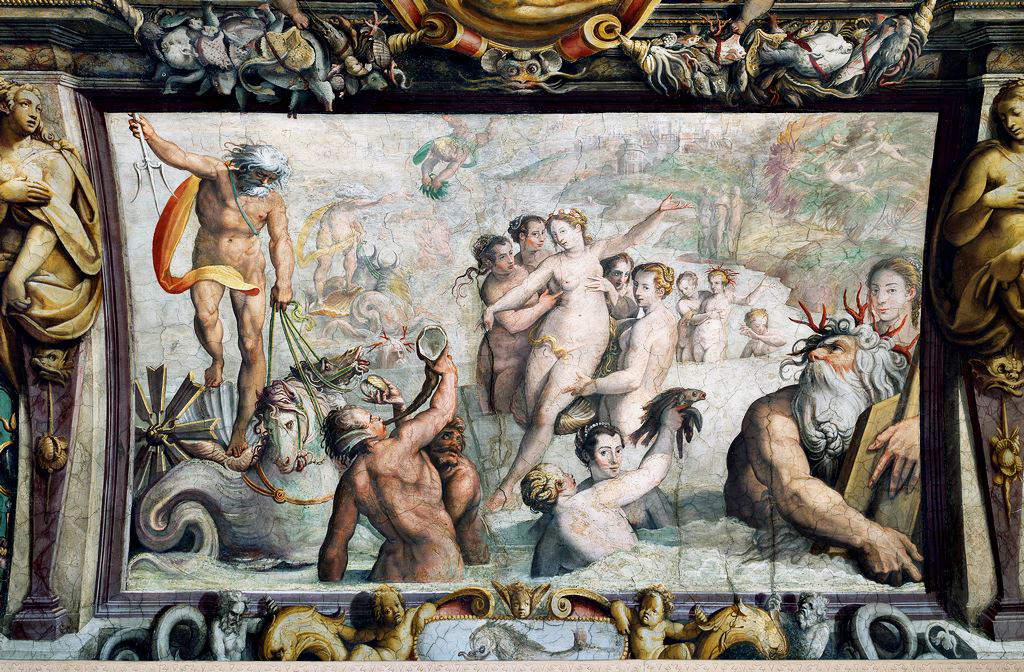

The subject matter is unusual and curious. The scene takes place on a long cliff on which sit several figures (mostly women, all naked) who show the relative an array of treasures recovered from the seabed: corals, shells, oysters, pearls, crustaceans of all kinds. In the foreground, on the small beach from which the cliff starts, are five figures arranged in a semicircle: three naked women adorned with pearls, an old man with a long white beard, who is also naked, and a cherub in the foreground, next to a monkey sitting on the sand, ironically wearing pearls, in an almost vain pose. To the left, another woman raises above her head an enormous spiny murice, behind still a companion looks toward us resting her head on her hand, and nearby a black man, modeled after the example of the Belvedere Torso (the two nymphs near the central figure have instead been related, by scholar Ianthi Assimakopoulou, to the poses of the figures appearing in the Roman sarcophagus of the Judgment of Paris at the Villa Medici in Rome), holds a bow with one hand and a parrot with the other. Further back still, we see a swarm of characters intent on fishing in the sea or returning to the islets in the background: a boat with two fishermen on the right is approaching the reef, there is a woman swimming after a profitable coral catch, and so on. On the horizon, the sky merges with the sea. The colors are bright, the complexions are rendered in luminous pearly tones, the sparkle of the rippling sea, and the details are rendered with miniaturist care and refinement and enhanced by the properties of copper, the material on which Zucchi painted the scene: even the formal values combine to make this work one of the most intriguing paintings of the late 16th century in Rome.

This is indeed a rare work, although it has an illustrious precedent, namely the Pearl Fishing that, some fifteen years earlier, between 1570 and 1572, Alessandro Allori (Florence, 1535 - 1607) had executed for the Studiolo of Francesco I in the Palazzo Vecchio. “Under the water,” wrote the man of letters Vincenzo Borghini, in a letter addressed to Giorgio Vasari in the summer of 1570, “has to be a fishing of pearls et of corals made by sea nymphs, et Tritons similar to that which you made in the hall of the elements: et will be very pleasant and vague.” The studio featured paintings with references to the four natural elements (water, air, earth, and fire): the Pearl Fishery, of course, referred to water. Jacopo Zucchi knew the Florentine precedent very well, having been one of the artists employed in the decorations, as did Cardinal Ferdinando, who would have remembered the painting his brother had made when he found himself deciding how to decorate his studiolo in the Palazzo Firenze, and in particular the cabinet that was reserved to house naturalia and artificialia, that is, curious objects from the natural and artificial world collected in a Wunderkammer (a cabinet that, moreover, we know was made of walnut wood, and had thirty-three drawers, twenty-four bronze statuettes and nine doors decorated with copper paintings). Zucchi’s painting, however, is much more allusive and enigmatic than Allori’s.

The intonation of the scene has led some scholars to interpret it as an allegory of the discovery of America, given the abundance of exoticism (the animals, the Moorish figures, the great abundance of treasures that was a topos commonly associated with the New Continent at the time) and given that the theme is often attested in the late sixteenth century. However, this is an unconvincing proposition: it is difficult to imagine that a painting so associated with the sea should be understood as an allegory of America (with which, if anything, the fruits of the land were usually associated rather than those of the sea). On a literal level, the painting can be read as a crowded scene of mythological character. The figure that stands out in the center, that is, the woman holding a coral in one hand and a shell with some pearls in the other, has been interpreted as the queen of the sea Amphitrite, Poseidon’s bride, because of the crown on her head (in Francesco I’s studiolo, moreover, there was a sculpture by Stoldo Lorenzi representing Amphitrite, which is still in situ today), while the other naked young women accompanying her are the Nereids, the nymphs of the sea. It is thus Amphitrite herself who presents the two most precious gifts of the sea, the pearls and the coral, almost as if to emphasize the importance of what was kept in the cabinet (presumably objects related to the sea or water), and therefore to invite its possessor to take due care of it. Elena Fasano Guarini, on the other hand, considered the work, in line with the decorations in Francesco I’s studiolo, to be an allegory of the Medici’s industries.

There is, however, a further level of interpretation, which requires a premise: small paintings such as these were reserved for the private contemplation of their patron, who at most might have decided to widen the very limited audience of recipients to a few lucky guests. It will be noticed how both Amphitrite and the two nymphs near her (but the same could be said for the other three in the foreground, although the resemblance is less clear) all have similar features. Already Baglione wrote that in those nude women were recognizable “many portraits of various very beautiful Roman Ladies of those times,” and indeed the scholar Edmond Pillsbury, author in 1980 of a study of Jacopo Zucchi’s “cabinet paintings,” proposed identifying Amphitrite with the Roman noblewoman Clelia Farnese, who in 1570 had married Giovanni Giorgio Cesarini and was a close friend of Cardinal Ferdinando: all on the basis of the very strong resemblance between Amphitrite of the Coral Fishery and the lady portrayed by Jacopo Zucchi in a famous painting in the National Gallery of Ancient Art (who is, indeed, Clelia Farnese). The illegitimate daughter of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese (nephew of Pope Paul III), she had been described by Michel de Montaigne, after his trip to Italy in 1580-1581, as “the most beautiful woman in Rome, without comparison.” However, that between Clelia Farnese and Ferdinando de’ Medici was perhaps something more than a friendship, and it was known even outside the rooms of the Roman palaces: the scholar Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, in the catalog of the exhibition Art and Love in Renaissance Italy, held at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, refers to the relationship between the two a pasquinata that, in no uncertain terms, read, “The doctor rides the Farnese mule.” Indeed, after Cesarini’s death in 1585, the relationship between the two became very close and it was rumored that Clelia had become the cardinal’s mistress. However, we do not know for sure what went on between the two and what the nature of their relationship was.

Of course, it would not have been the first time that a contemporary character was depicted in the guise of a pagan god (just think of what is perhaps the most famous example: the Portrait of Andrea Doria in the guise of Neptune, a work by Bronzino from about thirty years earlier, and preserved at the Pinacoteca di Brera). But it would really have been too much to see a noblewoman transfigured into a goddess, moreover naked, and moreover depicted next to a cardinal in the guise of the god Poseidon, an element absent in the Borghese Gallery version, but present in the Lviv version, where we observe a character dressed in the antique style and whose physiognomy can be well compared, Pillsbury suggested, to that of the portrait of the cardinal executed by Scipione Pulzone. For this reason it might not be peregrine, at least according to Pillsbury, to consider the Lviv painting (which he moreover published) as the original (were it not for the fact that the one in Rome is of higher quality): for the fact that the cardinal could have kept the painting in which he was depicted together with Clelia to himself, and circulated replicas without the compromising insert. However, it would have been equally disreputable, for the reputation of a character so concerned with discretion (even if he did not always succeed in preserving it: gossips had nicknamed him "Sardanapalus,“ after the legendary Assyrian king known for his dissolute customs), to put out works in which his mistress was depicted without veils: more likely, the derivative works were used to decorate other rooms. Besides, there was an unwritten rule in force at the time that a daughter of a cardinal (such as was Clelia, daughter of Alessandro Farnese the younger, the ”Great Cardinal") could not become the mistress of another cardinal. So it was in Ferdinand’s interest to keep the affair as concealed as possible.

In any case, Pillsbury cites a letter from Pietro Usimbardi, the cardinal’s secretary, in which he speaks of the ... licenses that the prelate liked to indulge in: “He did not lack inclination to lasciviousness, but this he always passed off without insult or violence of any kind, et with great respect for the nobility, who never had to complain.” There would be elements that would also suggest the feeling of inordinate love passion: the parrot, the monkey, the pearls, and even the two Moors are all symbols of lust. The Moors, moreover, for a reason that is inconceivable according to our morality: during the Renaissance, a time when Florentine merchants were very active in the slave trade, being at the center of the trade between Portugal and Italy, Christian morality considered the behaviors of Africans and their tendency to live scantily clad, given the latitudes in which they live, to be signs of uncontrollable bestial urges (Cardinal Ferdinand moreover had some Moorish slaves in Rome). A symbolism that the painting’s commissioner had purposely included to allude to less than chaste feelings toward Clelia Farnese, especially since the painting was her exclusive preserve? Hard to believe so, but in fact the resemblance is very high, and there is also another coincidence: in one of the frescoes in the Palazzo Firenze, theAllegory of Water, another work by Jacopo Zucchi, the face of Clelia Farnese appears again, who moreover turns her gaze to the viewer. And not only that: “to confirm, discreetly, that it is indeed her,” wrote Elinor Myara Kelif, “provides an emblem that leaves little doubt as to the young woman’s identity: the upside-down Farnese lily - and yet recognizable to the eye of a careful observer - reproduced on the figure’s lap. Clelia Farnese in the guise of Amphitrite, the bride of Poseidon, is thus associated with coral, a material with a complex and prodigious nature, endowed with propitiatory and talismanic virtues, and at the same time juxtaposed with Venus, particularly through pearls, attributes of the goddess of love.”

In essence, regardless of the more or less Platonic nature of their relationship, it is not improbable to think that the cardinal wanted to include the portrait of his beloved, nude, in this painting, so that he could contemplate her even when he was not present (and, if we are to give credence to the hypothesis that the variants were made to be painted for his other residences, also to have her with him at all times). Nor, however, is there any lack of interest even scientific interest on the part of Ferdinando de’ Medici, relating precisely to coral. Already Pliny, in his Naturalis Historia, had described more than forty natural remedies that could be derived from this animal (although, still in the Renaissance, it was believed to be a plant endowed with berries that were soft under water but capable of becoming as hard as stones when brought to dryness). Francesco I’s studiolo contains a famous painting by Giorgio Vasari, Perseus freeing Andromeda, designed to decorate a cabinet where a rich collection of corals was kept (mythology attributed the birth of coral to the contact between the blood of Medusa’s head, killed by Perseus, and some twigs that were on the water as the hero passed by: and Vasari had translated this myth into images in his painting). The studiolo’s collection numbered, according to an inventory, over forty pieces of coral, including twigs and worked coral objects: at the time, coral, harvested directly from the waters of the Tuscan coast (in the sixteenth century there were still a few small coral reefs in front of the coast), was prized not only for its beauty, but also for its medicinal and apotropaic powers.

So, Ferdinand de’ Medici, wrote Ianthi Assimakopoulou, "shared with his father Cosimo I de’ Medici and his brother Francesco the same fascination with naturalia and artificialia. Rare in nature, objects of lucrative trade, masterfully employed in jewelry as well as in the decoration of semi-precious stone tables produced in the workshops of the cardinal’s Roman palace, corals received Ferdinand’s special attention. [...]. All these factors in combination with Ferdinand’s taste for antiquity probably motivated his commission of The Kingdom of Amphitrite or The Coral Fishery, or rather a painting that blends both themes, mythological and historical." Without neglecting, of course, the desire to celebrate the lover.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.