Jean Dubuffet’s relationship with the city of Venice could be defined, in a jargon consonant with social media, as a “complicated relationship”; a sort of love-hate that began with a heavy rejection, continued with an idyll, and resurfaced a few years ago, in a flashback in a neo-Gothic setting, when, seventyyears after that first refusal ended up on the pages of a series of epistolary exchanges, the founding artist of Art Brut was made the protagonist (it was 2019), of a delightfully staged exhibition at Palazzo Franchetti, an ancient building from whose polyphors, while walking down the monumental staircases inside, one enjoys an extraordinary view of the Grand Canal.

In a letter dated November 11, 1949, addressed to Venetian publisher Bruno Alfieri, Dubuffet, following the latter’s invitation to organize an exhibition in Venice, states after thanking him: “It would be preferable to choose for an exhibition of my work in Venice a time when there are in the city neither the Biennale nor retrospectives of cultural schools, nor art critics, nor personalities from the Museum of Modern Art.” Toward the Venice Biennale, Dubuffet has a very critical stance, evidenced by the fact that “a regatta club is already more alive and more attractive than a gallery of paintings,” and that “a circumstance that would load an exhibition of paintings with meaning would be quite another thing than the Biennale.” All the art that art critics, museums and their art guards, painting dealers and their regular customers deal with is considered by Dubuffet to be false art, the false currency of art. Through a determined rebellion, the artist declares how he cares little about frequenting the same places that the protagonists of false art frequent and exhibiting with them, for he feels that he is artistically far removed from them.

And continuing with his rebellious but still topical predictions, he says, “it will happen that Venice, intoxicated more than any other city by certain mobilizations of false art, will one day reach such a degree of saturation that it will be driven to angrily take the opposite road and turn its back on all this falsehood,” and adds: "the healthy elements of this city will then set fire to the Doge’s Palace and the Bridge of Sighs and all those hateful pseudo-artistic antiquities, and throw out of the city all those imbecile tourists who organize congresses and hang Pen Club members from the irons of gondolas, and then the time will have come for me to make an exhibition, in this city finally returned to serious concerns worthy of my paintings.“ By ”mobilizations of false art," the artist alludes to the exhibitions of Picasso and other Frenchmen at the XXIV Biennale, that of 1948. His position is well evidenced in an article entitled He Wants to Set the Doge’s Palace on Fire, which appeared in an independent weekly, in which we read that “Jean Dubuffet has for some years now declared war on all ’official’ painters, that is, Picasso, Braque, Matisse, etc., on all fronts of art. He solemnly affirms that he hates them first of all for their prosopopoeia and the publicity hype that accompanies their every gesture, and secondly for polluting modern art with a series of aesthetic theories and even ignoble attitudes. From an aesthetic point of view they are worth nothing, absolutely nothing. All their painting is wrong because it is based on concepts such as ’form,’ ’content,’ ’harmony,’ etc., which are outdated and completely false. ’Official’ painters go so far as to distort a painting only to obey formal requirements or for the sheer sake of expressionistically accentuating details. But under the layer of color there is nothing at all, only lies and falsehood.” The article then goes on to clarify how the artist would solve the formal problem agitating the souls in his contemporaries, that is, by creating “a redemptive movement against the formalistic aesthetic canons that suffocate us, let us return once and for all to ’raw’ art, to ’art brut,’ let us completely demolish all our rancid, bourgeois cultural superstructure. The result of Dubuffet’s ’theories’ is a painting vaguely reminiscent of prehistoric graffiti, Negro art, childish drawings made with chalk on the wall of your house [...]. But a fresh and genuine air circulates in these drawings, in these temperas. The composition is at least free from any impediment of rhythm, coherence and balance.”

“Le temps est venu d’un art sérieux,” the artist himself declares in a letter dated March 1950, still addressed to Bruno Alfieri: “soon the art so futile of our fathers will no longer interest anyone, and much more will be demanded of art than what they demanded of it.”

All this documentary material gives a good idea of Dubuffet’s rebellious and revolutionary character: it certainly was not so usual at the time to meet an artist who would counter the Biennale circle, let alone an artist who would publicly declare his desire to see symbols of the city of Venice burn, resulting in the incendiary image of the Doge’s Palace and the Bridge of Sighs in flames, in order to see serious art, real art as opposed to fake art, finally triumph.

The two curators of the 2019 exhibition, Sophie Webel and Frédéric Jaeger, had brought Dubuffet’s rebellious art back to the city of the lagoon, seventy years after that first categorical no, because after all, the situation today has not changed that much: Venice continues to host Italy’s most worldly and most international art event, while Dubuffet’s works tell the story of an artistic career marked by indifference to glory and an almost total rejection of anything that could be defined as worldly and conformist. His work history has always been considered provocative, despite the various evolutions of his production.

The author of the definition of “Art Brut,” which was intended to designate the works of those who did not belong to cultural institutions and artistic groups or movements, Jean Dubuffet was convinced that in order to be inventive, the work of art had to be spontaneous, far removed from cultural stereotypes and alien to all professionalism. This term first appeared in 1945, at a time when the artist had embarked on his first trips to Switzerland and France in search of marginal works of art, with which he came into contact mainly in psychiatric hospitals; two years later he founded and organized the Compagnie de l’Art Brut, whose members included André Breton, Jean Paulhan, Charles Ratton, Henri-Pierre Roché, Michel Tapié and Edmond Bomsel. It would be in 1949 that he would publish the text L’Art Brut préféré aux arts culturels in the exhibition’s catalog for a group exhibition of Art Brut at Galerie René Drouin, in which he defined the concept of Art Brut: “works executed by people free from artistic cultures, where imitation, unlike what happens among intellectuals, has only a small part or is null, so that their authors draw everything (subjects, choice of materials, tools of transposition, rhythms, ways of writing, etc.) what comes from their heart and not clichés of classical art or fashionable art. We witness a pure, raw artistic operation, reinvented at every stage by its author, based solely on his own impulses. Art whose only inventive function is manifest.”

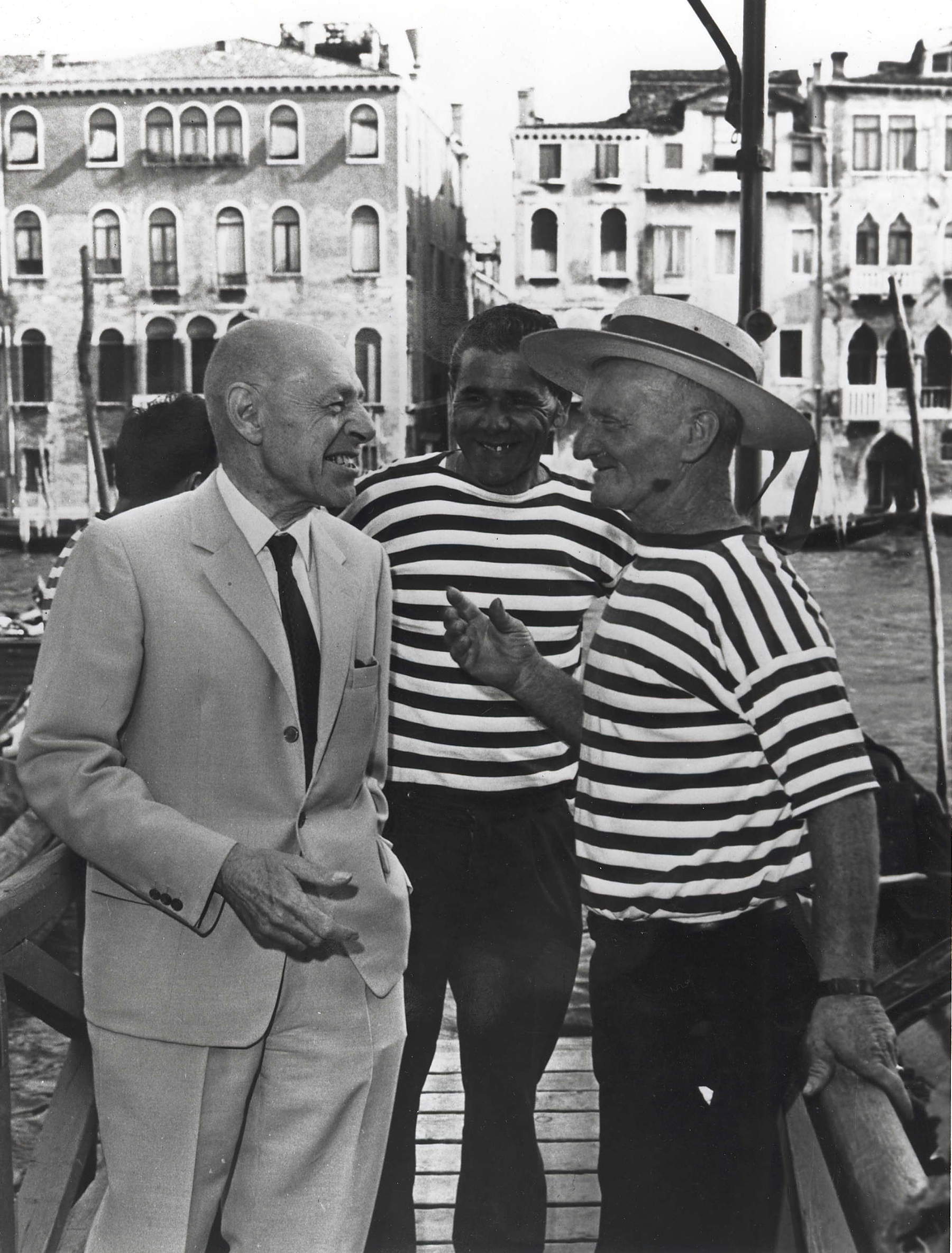

As mentioned, Dubuffet’s art has undergone several transformations in the course of his production, and the exhibition at Palazzo Franchetti aimed to return visitors, in addition to the artist’s relationship with Venice, to the memory of his most significant series, each of which is strongly different from the others: through the exhibition itinerary, well outlined by the two curators, the public retraced the fundamental stages of his artistic evolution. The review began with works from the Sols et terrains series completed between 1956 and 1960, to which the Matériologies and Texturologies are assimilated: these are works with earthy and tragic tones that intend to reflect on the infinite effects of matter. They refer to the topographical elements of the world, such as earth, water, sky, and stars, thanks to the particular effect that seems to reproduce them artificially. Through their metallic blacks, grays and silvers, we seem to see pieces of earth’s soil or stars and water surfaces observed through the lens as protagonists of his works; nature is thus depicted through illusion or artifice. The reproduction of nature, particularly in the Texturologies, is created through the visualization of textures, both material and immaterial, using lithographic impressions. These large series of lithographs have been called Phénomènes, as they make manifest the material aspect of phenomenal realities. Examples in the exhibition are Texturologie XXXV (prune et lilas) or Nuancements au sol (Texturologie XLIII), both from 1958 or again the elaborate Théâtre du sol from 1959. The term Phénomènes was also chosen as the title for Jean Dubuffet’s exhibition Les Phénomènes held in Venice, at Palazzo Grassi, from July 5 to September 1, 1964. It was one of two exhibitions held almost simultaneously at the Venetian museum venue, at the same time that the Biennale was also underway: the artist did not fail to point out that his double exhibition was in counterpoint to the latter. Another exhibition to constitute the triumphant pair was Jean Dubuffet’s L’Hourloupe, at the Palazzo Grassi Theater from June 15 to September 13, 1964.

The initial rejection of the late 1940s had turned into a consensus, despite his constant stance towards the Biennale: in fact, the 1964 event was a milestone in the Dubuffet-Venice relationship, as for the first time his works were presented in the lagoon city with a monumental double solo show. “It amuses me to present my unpublished works for once in Venice instead of Paris,” the artist had declared, but there were also many doubts.

In a letter dated December 1963 and addressed to collectors Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Colin, he says he has been working very assiduously for two months on large paintings: “these are paintings from that new and unseen style that has occupied me for a year and a half (since the ’Paris-Circus’ exhibition at Galerie Cordier in June ’62). All those new works completed a year and a half ago have so far remained in my hands; very few people have seen them and nothing has left my studio. They will be the subject of a major exhibition in Venice next summer, at Palazzo Grassi (which is run by Paolo Marinotti). It amuses me to present my unpublished works for once in Venice instead of Paris. However, it is not certain that these new paintings will be understood by the public; rather, I fear that they will not be. These new works take things to a plane to which the public is, I think, not yet quite ready, and is in great danger of running away from them or rejecting them. However, these works give me great satisfaction.”

Addressing Sidney Janis, a collector and gallery owner, and inviting him to his Palazzo Grassi exhibition for the opening date of June 15, 1964, he wrote in April of that year, “For the past two years I have been working on paintings with an unforeseen and unprecedented style and spirit, and with which I am very fond [...]. They are large in size. I wonder how they will be received by the public. They take art to a very risky and difficult plane that has a good chance of being misunderstood. That will be what will happen. It will be a novel presentation since none of these paintings in this style came out of my studios. I needed to have them all in front of me and I also wanted to show them all together and not scattered. It is this decision (and also that of wanting to sell far fewer of my paintings now and to keep more of them) that motivated my discussion with Cordier, which you have probably heard about. The exclusive distributor formula, which I had adopted with him and which worked for a few years, caused great inconvenience. I now intend to follow a regime of complete freedom at my leisure, reserving the right to keep my paintings even for a long time.”

Despite his concerns, the 1964 double Venetian exhibition proved a great success, both with the public and critics. One hundred paintings by Dubuffet, an example of masterful illusionism, reads the title of an extensive “special report” that appeared in La Stampa the day after the opening. And it immediately declared the new interest in the work of Dubuffet, “a French artist who is looked upon with so much interest today,” evidenced by the major exhibition that “in an exemplary way documents the last phase of Jean Dubuffet’s art.” The eulogies continue in the article, stating that he is “one of the most stimulating and fascinating personalities to come to the forefront of contemporary art in this postwar period,” pointing out that this is “the first time that an exhibition has proposed such broad and immediate contact between artistic production and the public, usually limited to a few isolated works.”

Particular attention had been aroused by the new L’Hourloupe series, of which more than 100 works, including oil and vinyl paintings, temperas and drawings, were on display. Dubuffet called it a “unitary” cycle, to which he gave the name Hourloupe, which is a term of his own invention without a precise meaning: the assonance with the term tourlouper, or “to turlupinate,” underscores the artist’s desire for a subtle turlupination, a kind of deception of which the viewers of these works are victims. And part of this deception are also the titles of the works themselves, which refer to misunderstanding, error, illusion, the subtle game between being and appearing. “A very fine game with which these figurations set up camp in the space, attacking it, crowding it like a weft that insinuates itself into the warp of a great tapestry, it is thus as if it were led by a leavening imagination that every material error redeems, making indeed of every equivocal form, a mysterious, possible truth,” comments the cited article. Dubuffet himself stated how it is often difficult to say “where truth ends and error begins. The important thing is not to cheat.”

Dubuffet’s intent was also to allow the viewer to derive a true reading of that narrative through the images and the graphic elements within them: an objective underscored by the subtitle of the L’Hourloupe cycle, “maieutics of the sign.” Renato Barilli, in the 1964 exhibition catalog, intends to make clear how from a kind of stylization that Dubuffet performs on a crowd of “gesticulating figures,” he manages to “set them within precious contours, to transpose them into ornamental motifs.” “It is a spectacle of the highest interest,” Barilli continues, “to follow the artist as with a ’ballpoint pen’ or ’Condor’ pen he is tracing on a sheet of paper his elegant cellular pavement.” In the works in the cycle, no corner is left blank: it is through the use of multi-color hatching that the artist is able to “fake a multi-dimensional space, playing on every most ambiguous rendering of sign as well as color.” Out of these horizontal, vertical and transverse lines go planes, subplanes and intersections, from which spring characters, objects and landscape details that highlight Dubuffet’s great inventive and imaginative capacity. It is amazing how from simple graphic signs and primary colors, such as brick red, blue and yellow, bewitching, eye-catching works are created. Clear examples of this are Site urbain, Époux en visite, Veglione d’ustensiles, Escalier VII, Le bateau II, Tasse de the VII, Cafetière VI, Site aux paysannes, and Le village fantasque, where everyday objects, characters, means of transportation, and city scenes are staged to take on a playful and imaginative character. The monumental sculpture Tour aux récits also belongs to the same cycle.

The 2019 exhibition concluded by presenting the third and final cycle of works created by Jean Dubuffet: these are Mires, paintings totally different from both Texturologies and Matériologies and L’Hourloupe. This cycle once again testifies to the artist’s great ability to follow a completely new thought and style. And it is surprising when one considers that Mires was conceived and made when the artist was already over the age of eighty. In fact, the series was the protagonist of the official exhibition held from June 10 to September 15, 1984 within the French Pavilion at the Venice Biennale: it was the first time the French Pavilion dedicated an exhibition to a single artist. Sharply criticized at the time of her famous rejection, now the artist was officially representing France at the 1984 Biennale. The circumstance was criticized by some and celebrated by others, but in fact the decision to participate in the Venice Biennale further highlights the artist’s freedom. As free are the thirty-four unpublished paintings presented that year; Palazzo Franchetti now exhibits over twenty of them.

Mire G 137 ( Kowloon) , Mire G 48 (Kowloon), Mire G 198 (Boléro), Mire G 189 (Boléro) and all the other paintings belonging to the Mires cycle express his new worldview, which he makes explicit in a letter addressed to Monsieur Gaiano: “many few people will be able to approve (and conceive) this moment when not only the definable object or figure but also the whole concept and the whole humanistic superstructure cease to exist. Everything we think we perceive and consider reality seemed illusory to me, all words (and the concepts they define) seemed useless. I may have wondered what they are coming to the Venice Biennale - a shrine to humanistic celebrations - with paintings that arise from similarly negationist views.” In these works, “the eye gets lost in a jungle of lines and instinctive strokes,” as stated in an article published in CNAC Magazine. Those on a yellow background are called Kowloon, while those on a white background Boleros. They spread great freedom, youth and freshness, thanks to their bright colors, which, however, do not represent anything known. "By the term Mire is meant to focus the gaze on any point in a continuous structure, where the intellect has not yet intervened,“ but ”these paintings are the opposite of abstraction: they depict continuous spectacles that express a new gaze, brought into the world once the repertoire of definable things has been forgotten," Dubuffet himself had declared.

The three most significant series of the artist’s production were accompanied and commented on at the 2019 exhibition by newspaper and magazine articles relating to the openings of the master’s three Venetian exhibitions, by photographs illustrating the layouts of the latter, and above all by letters the artist had exchanged with the publisher Alfieri and various collectors. The two curators had thus skillfully crafted an exhibition that tells exhibitions, tracing Dubuffet’s artistic evolution and his relationship with the lagoon from documents and epistolary exchanges. A very productive exercise for visitors. And now the question arises: was this the definitive end of Dubuffet’s troubled relationship with Venice?

This article was originally published in No. 3 of our print magazine Finestre Sull’Arte on paper, and is republished today slightly updated... Click here to subscribe.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.