What are the stars of Vercelli’s museums, those must-see masterpieces that tell the city’s story because they are closely linked to the area? Although the Piedmontese city usually falls outside the circuit of Italy’s major urban art centers, Vercelli holds works of international appeal that are testimonies to the cultural and social life and historical events that have taken place in the area.

Leaving art aside for a moment, although not as much as it seems, the Vercelli landscape is dominated by rice cultivation, so much so that Vercelli is considered the “European rice province.” in fact, the rice fields stretch for miles and miles, and although today work in the paddy field has become completely mechanical, one does not forget the days when it was the women, the so-called mondine, who spent entire days barefoot, with water up to their knees and with their backs bent in the fields to remove the weeds that would otherwise prevent the rice seedlings from growing. Hard work in heavy conditions, often poorly paid, was well depicted in a famous painting by Angelo Morbelli (Alessandria, 1853 - Milan, 1919) from 1895 - 1897: For Eighty Cents!, a title that refers, with a clear intent of social criticism, to the reduced pay of the mondine despite working hours that were at least twice as long as eight hours. The first strikes in the rice fields to obtain the eight-hour contract and fairer wages date back to those very years: it took until 1906 for these rights to be achieved. The work can be considered the star of the Burgundy Museum because it is often loaned for exhibitions of international scope, but above all because it is a true cross-section of the social and economic history of the Vercelli area and the typical rice crop, which has become a unique heritage in Europe. The women rice field workers depicted here proceed backwards, in two rows, and with their legs in the water and facing backwards transplant rice seedlings. This is a strongly pointillist work to which the artist chooses to give a photographic slant, bringing into the frame only the fields and the women at work. The painting has been part of the Burgundy Museum’s collection almost since the museum opened its doors to the public: in fact, it was purchased in 1912 at the Irrigated Countryside Art Exhibition held in Vercelli.

The museum was opened four years earlier, in 1908, on the will of Antonio Borgogna (Vercelli, 1822 - 1906), a lawyer who was passionate about art and travels he made both in Italy and abroad. He was a great collector of the rich bourgeoisie of the late 19th century, as well as a well-known philanthropist: he helped the city’s schools financially, financed many public monuments, including the city’s first drinking water fountain, and supported women and young artists with scholarships. However, the museum building, which before being opened to the public constituted his house-museum, is named after Francesco Borgogna, the collector’s father, to whom he owed everything, “life, feelings and riches”: he was to bring together his collection (which he called the Gallery) that included a complete repertoire of all arts and artistic techniques.

Today, the museum holds more than eight hundred works arranged on three exhibition floors: in addition to paintings sculptures, ceramics, micro-mosaics, semi-precious stone commissions, furnishings, and furniture collected by Borgogna himself, pictorial, sculptural, graphic, and decorative masterpieces ranging from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries, including detached frescoes and altarpieces from the Renaissance, are on display. Particularly significant are the works that bear witness toPiedmontese Renaissance art: altarpieces, polyptychs, fresco fragments, and panels created by Defendente Ferrari, Gaudenzio Ferrari, Bernardino Lanino, Gerolamo, and Giovan Battista Giovenone. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century painting, on the other hand, is represented by artists such as Ludovico Carracci, Sassoferrato, Elisabetta Sirani, Genovesino, and Carlo Maratta; also present is a notable collection of Flemish and Dutch paintings (over fifty). The nineteenth century includes, among others, works by Massimo D’Azeglio, Gaetano Chierici, Gerolamo Induno, Francesco Lojacono, Giacomo Favretto, as well as the Divisionist painting by Morbelli already mentioned. Finally, the exhibition concludes with 20th-century works by artists from Vercelli and Piedmont who were added to the collection after Borgogna’s death, such as portraits by Ambrogio Alciati, Giacomo Grosso, and Francesco Menzio, landscapes by Clemente Pugliese Levi, Lorenzo Delleani, and Umberto Ravello, monumental canvases by Giuseppe Cominetti, and sculptures by Francesco Porzio.

The Borgogna Museum thus offers a cross-section of the history of Italian painting, especially Piedmontese, but also works that go beyond national borders, for example Dutch and Flemish, as well as Caravaggio-derived paintings and paintings that tend toward classicism. For a long time the museum was considered the"second picture gallery in Piedmont, after that of the Galleria Sabauda in Turin," both in terms of the quality and quantity of the works. Now the intention is to return the museum venue, in the beautiful neoclassical building, to its identity: from a house-museum to a picture gallery, to a museum of the territory that holds masterpieces from abandoned churches or private individuals.

|

| The Borgogna Museum in Vercelli |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, For Eighty Cents! (1895-1897; oil on canvas signed and dated, 67.5 x 121.5 cm; Vercelli, Museo Borgogna) |

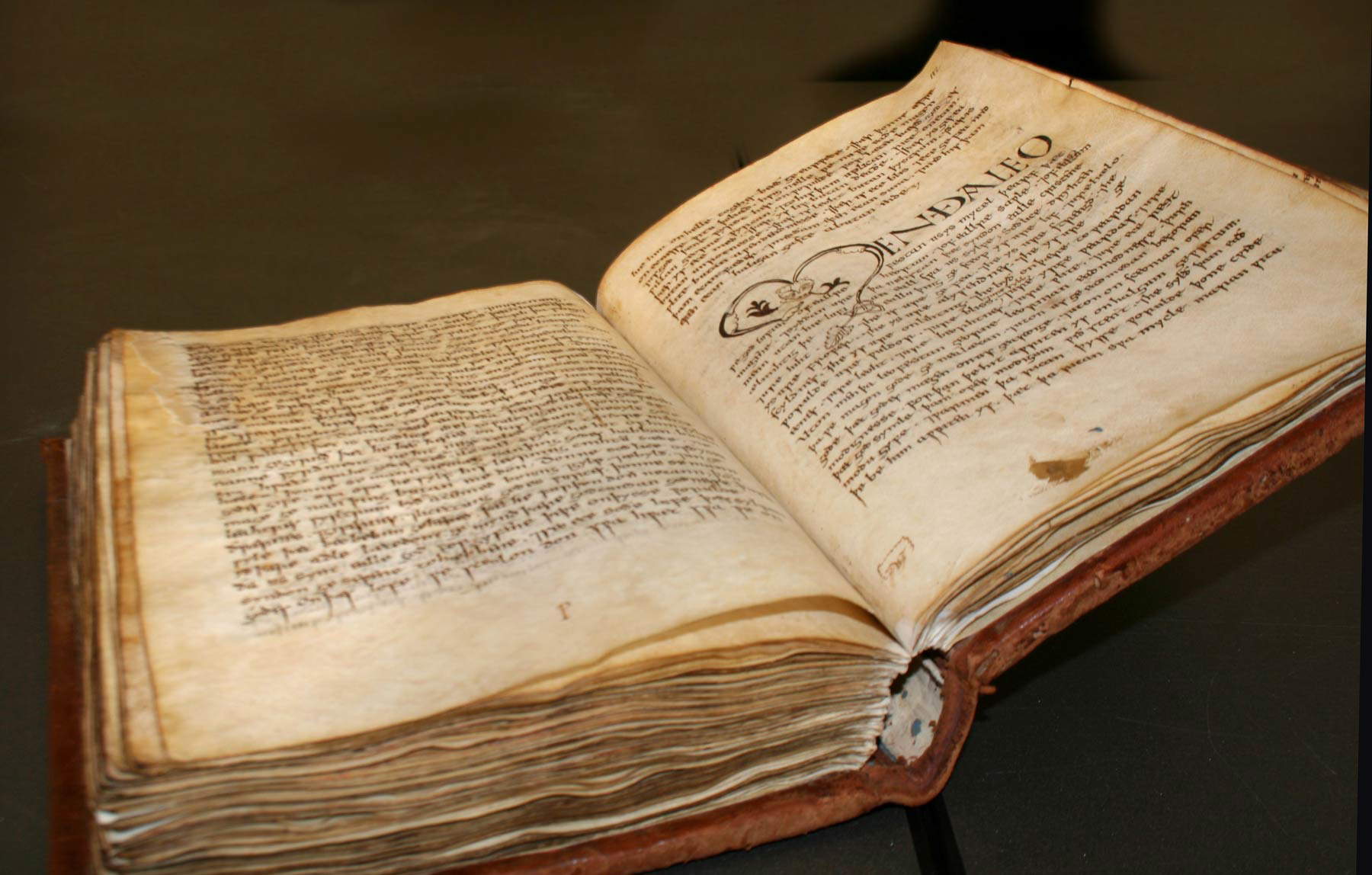

More properly religious is the Cathedral Treasury Museum with its Library and Chapter Archives, linked to the diocese of Vercelli and the Cathedral of St. Eusebius, the first bishop of the city and of Piedmont. Located in a wing of the Archbishop’s Palace, the museum displays works of goldsmithing, liturgical furnishings and fittings, textiles and paintings that belong to the Cathedral’s heritage. Through the works preserved, one takes a journey not only through the multimillennial history of the Vercelli diocese , but also along the political and social events of the city. Vercelli was a privileged stop on the Via Francigena, which people came to in order to admire the magnificent Cathedral, seat of the oldest diocese in Piedmont, and the precious Ottonian Crucifix dating back to the 10th century made of embossed and partly gilded silver foil with a crown decorated with precious stones, the original filling of which is preserved in the museum. A symbol of the prosperity of the diocese of Vercelli, which at the time was one of the richest cities in Italy, commissioned by Bishop Leo of Vercelli. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance the bishops of the diocese enjoyed important power and were often involved in the political events of the city, and great patronage involved metals, textiles and paintings in those days. Also significant were the interest in and devotion to reliquaries both anciently and in modern times. All of these themes can be discovered and learned about by visiting the museum. Let us not forget that the treasures of the Cathedral include splendid medieval illuminated manuscripts: in fact, one could say that the stars of the Cathedral Treasury Museum complex are them. In addition to the Vercelli Book, a mysterious manuscript dating back to the 10th century whose history originated in England, there are 260 codices: among them is Codex A or Codex Vercellensis Evangeliorum attributed to St. Eusebius. It is a Vetus Latina, or translation from Greek to Latin of the four canonical Gospels, dating from the second half of the fourth century. The codex remained in use until the early Middle Ages and then became a true object of devotion, so much so that some sheets were donated as relics; the manuscript is kept in the Chapter Library, while the silver binding can be seen in the Museum. The latter dates from the donation of Berengarius Rex in the second half of the 10th century and one can recognize a Christ in mandorla, symbols of the Evangelists and St. Eusebius himself depicted standing in bishop’s robes. One can also read a dedicatory inscription referring to the commissioner King Berengar: it is unclear, however, whether it is the I or the II, his nephew. It is nevertheless to be regarded as a valuable Ottonian testimony to Vercelli art.

One more curiosity: on the upper floor of the museum are the Pope’s Rooms that commemorate Pope John Paul II’s visit to Vercelli in 1998 and important Renaissance patrons, such as Pope Julius II who was bishop of Vercelli between 1502 and 1503. The latter donated to the Cathedral the chasuble (displayed in the Museum of the Cathedral Treasury) and the cope, both woven in Venice and embroidered in the Flemish-Burgundian area.

|

| Museum of the Cathedral Treasury, first room |

|

| Museum of the Duomo Treasury, second hall |

|

| Museum of the Cathedral Treasury, Pope’s room |

|

| Vercelli Book (Second half of 10th century; parchment and leather bindings on 18th-century wooden boards, 325 x 220 mm, southeastern England; Vercelli, Metropolitan Chapter of the Cathedral of SantEusebio Vercelli, Chapter Library, ms CXVII) |

The Leone Museum is owed to Camillo Leone, a notary and collector from Vercelli who lived in the 19th century: it was opened in 1910, three years after his death, in what had been his home since 1871, Palazzo Langosco. Before becoming his property, the late Baroque-style palace frescoed and decorated with 18th-century stucco belonged to the noble Langosco family of Casale Monferrato. Camillo Leone, when he still lived there, had earmarked some rooms to house his own art collections, which were difficult to label, however “ancient objects of any kind and nature,” as he himself stated in his will. Today Palazzo Langosco holds collections of applied art, watermarks and weapons from the 16th to the 19th century.

Also part of the Leone Museum is Casa Alciati, a Renaissance-style mansion: inside is one of the most important fresco cycles of early 16th-century Piedmont. It depicts mythological, historical, and religious subjects, but the authorship remains unknown to this day (however, it is thought to have been created by a numerous group of artists since it is very large). The cycle can probably be dated to between the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the third decade of the 16th century and shows derivations from translation prints and decorative inventions of archaeological taste, as well as a careful awareness of the new Roman fashion, drawing on the painting of Michelangelo Buonarroti, Baldassarre Peruzzi and Raphael Sanzio. The frescoes were rediscovered only in the 1930s during renovations. The two buildings are connected by a “connecting sleeve,” built in 1939 for the exhibition Vercelli and its province from Romanity to Fascism for Benito Mussolini’s visit to Vercelli.

The Leone Museum thus consists of three buildings from three different eras: the Baroque Palazzo Langosco, the Renaissance Casa Alciati, and the 20th-century connecting wing.

The star of the museum is Cardinal Guala Bicchieri’s casket with enameled medallions of Limousin manufacture dating from 1220 - 1225. The fifteen reservé gilded copper medallions show engravings with secular subjects, except for the one depicting Saint Jerome and the lion: themes related to hunting, chivalry, and courtly love. Two medallions are then allegories of the months of February and April, while another depicts two half-naked wrestlers. The cardinal is credited with initiating the construction of the Basilica of Sant’Andrea in Vercelli, and it was to the abbot of the Basilica, Tommaso Gallo, that he donated the exquisite casket in 1224: it is the only object belonging to Guala Bicchieri still present in Vercelli. Camillo Leone bought it on the antiques market in 1883 for the sum of 8,000 liras. And to this day it is still on display at the Leone Museum.

|

| The Leone Museum |

|

| The Leone Museum |

|

| The Leone Museum |

|

| The MAC - Civic Archaeological Museum |

Finally, we go much further back in time, to Vercelli’spre-Roman and Roman times , through the exhibits in the MAC - Museo Archeologico Civico “Luigi Bruzza,” named after the Barnabite father who studied and dedicated himself to Vercelli’s history and archaeology. The museum is located in the “medieval sleeve” of the former monastery of Santa Chiara and houses over six hundred artifacts found during excavation campaigns. Here, therefore, one has the opportunity to learn about the ancient history of the Piedmontese city, from the settlement of the Libui, a population of Celtic origin who occupied the present city center, to the Roman occupation, and finally to the crisis of the city in late antiquity. Significant is the presence of a relevant number of Roman coins from the Constantinian period, although almost the entire numismatic corpus of Vercelli is preserved in the deposits of the Royal Museums of Turin.

Art, history, religion, traditions and social life are interwoven in the collections, albeit different, of the museums of Vercelli, each with its own characteristics but united by the desire to make known the rich and important heritage of the city.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.