by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta, published on 23/11/2018

Categories:

Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Max Klinger's 'A Glove' series of prints is one of the earliest depictions of a dream in art history and would go on to influence twentieth-century art.

"Klinger straddles inner worlds and reality, in a dialogue between an inside and an outside that is the motif of his creative genius. In his etchings the unconscious bursts into reality, taking hold of it and thus becoming tangible. Influenced by artists such as Arnold Böcklin, from whom he borrowed that dissension between love and death that is among the privileged themes of his creative journey, he looked with admiration at his sister art, music, in an attempt to bring to life the total artwork pursued by Wagner." So write, about the art of Max Klinger (Leipzig, 1857 - Gro�?jena, 1920), the two curators (Patrizia Foglia and Diego Galizzi) of the exhibition Max Klinger. Unconscious, Myth and Passions at the Origins of Human Destiny, which between September 15, 2018, and January 13, 2019, at the Museo Civico delle Cappuccine in Bagnacavallo set out to illustrate the importance of the German painter, sculptor and engraver’sgraphic art. In order to enter the imaginative mind of this extraordinary artist, and to understand how precocious were the interests that would later characterize much of his entire printed production (the aforementioned disagreement between love and death, but also the interest in dreams, the unconscious, and fantasies), it is possible to start from one of his youthful masterpieces, as well as one of his most famous works, the series of prints entitled Ein Handschuh (“A Glove”). Klinger published it as a first edition in 1881 for the types of Friedrich Felsing in Munich, but the conception dates back to the previous year, and the first pen proofs are even earlier, since they were created in 1878 (by a Klinger just 21) and exhibited the same year in Berlin. By the second edition, however, the artist wanted to change the title, and the series thus became Paraphrase über den Fund eines Handschuhs (“Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove”). The series, from its first exhibition in 1878, was a great success.

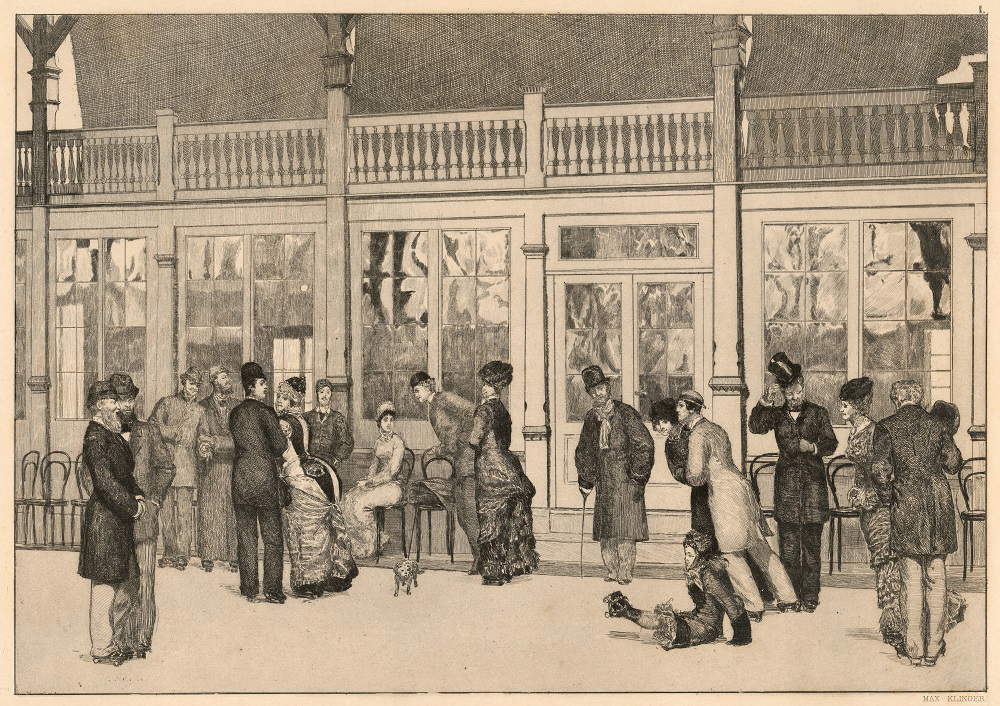

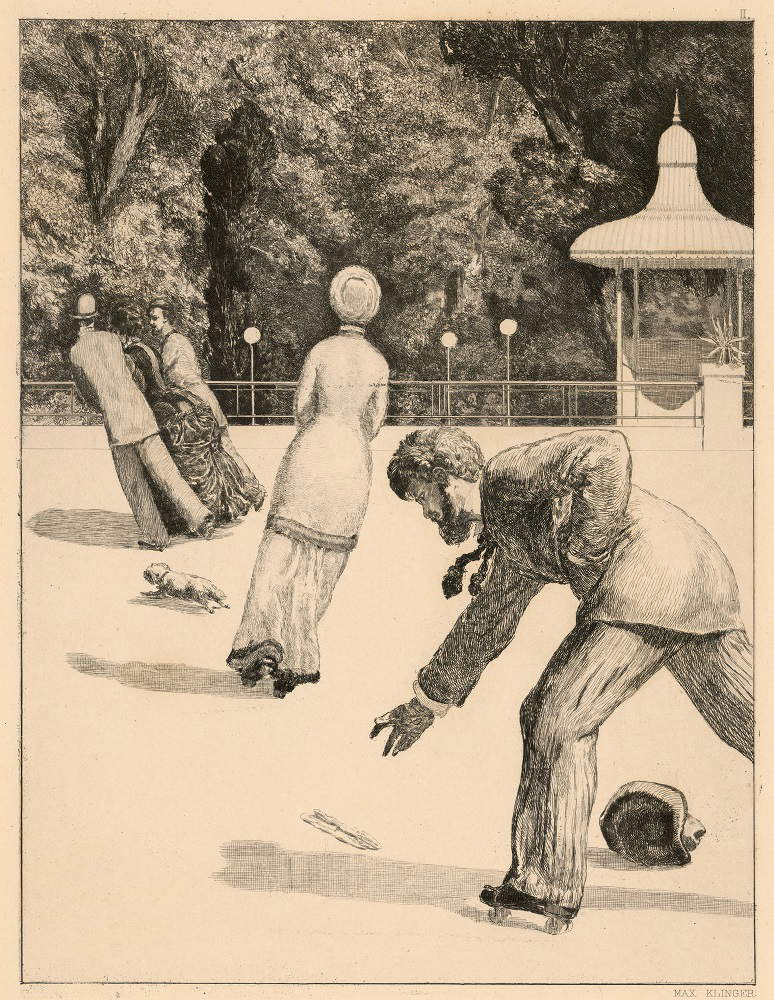

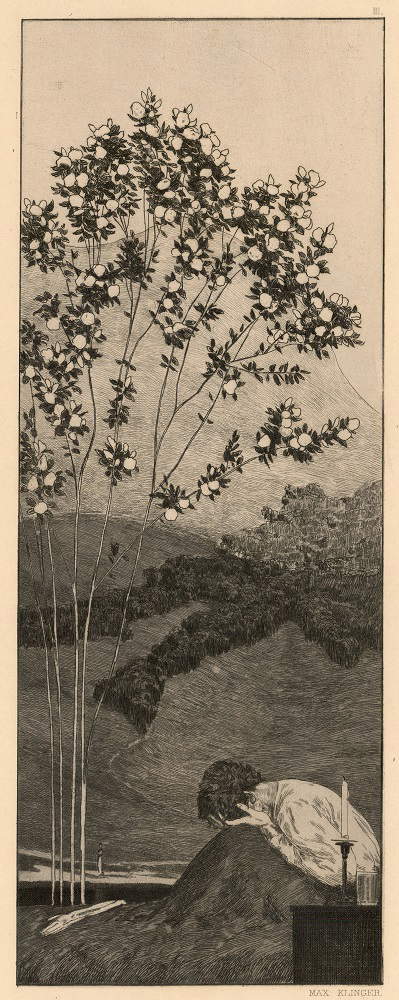

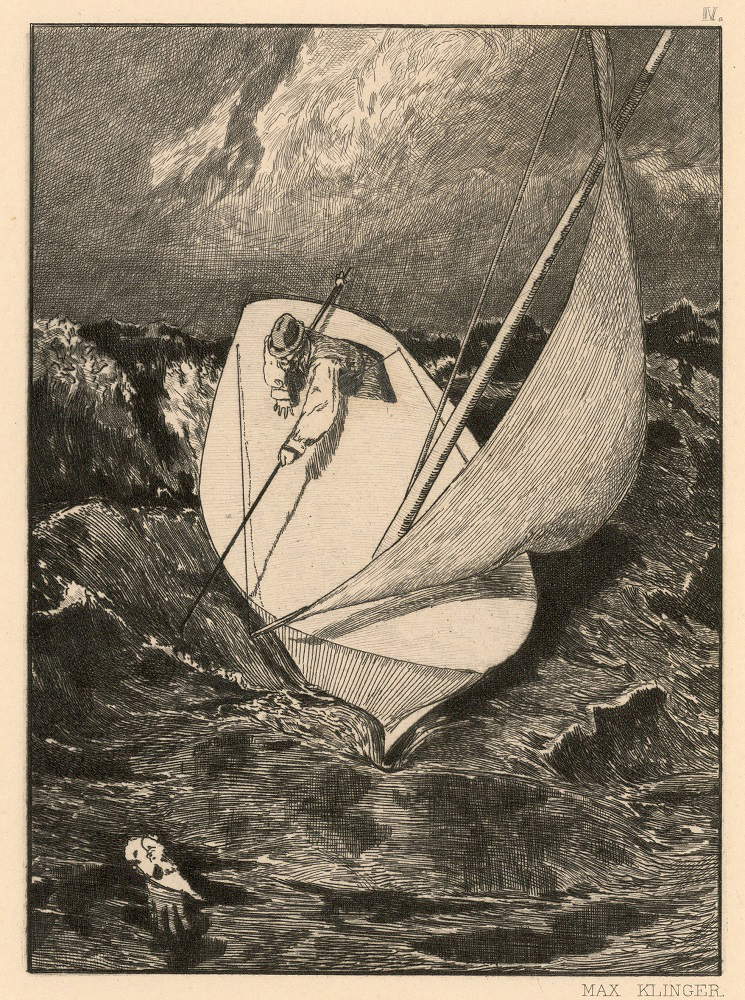

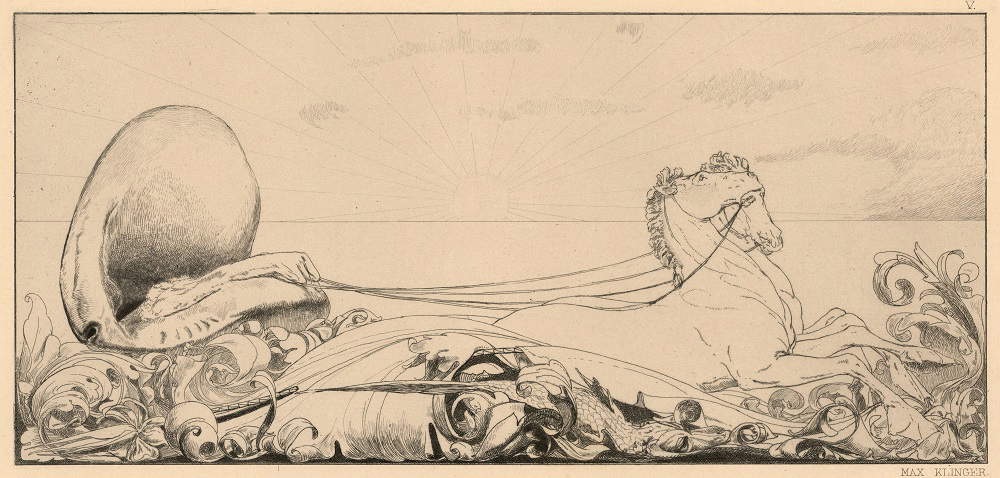

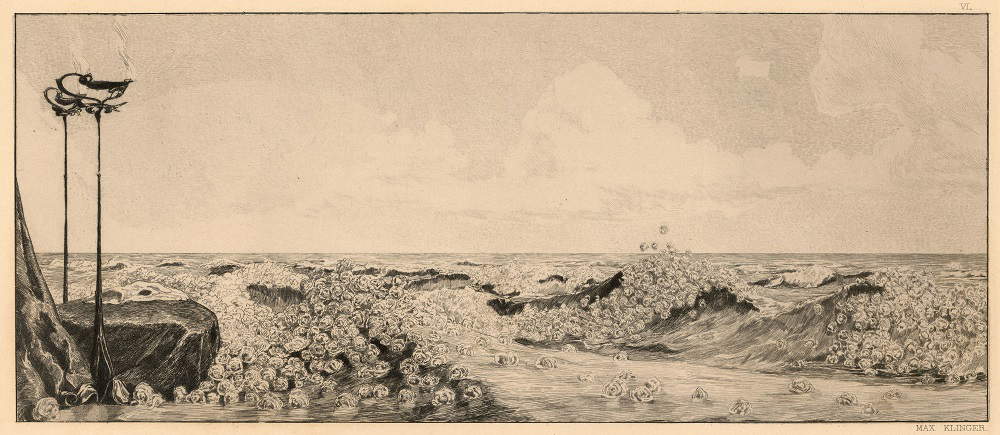

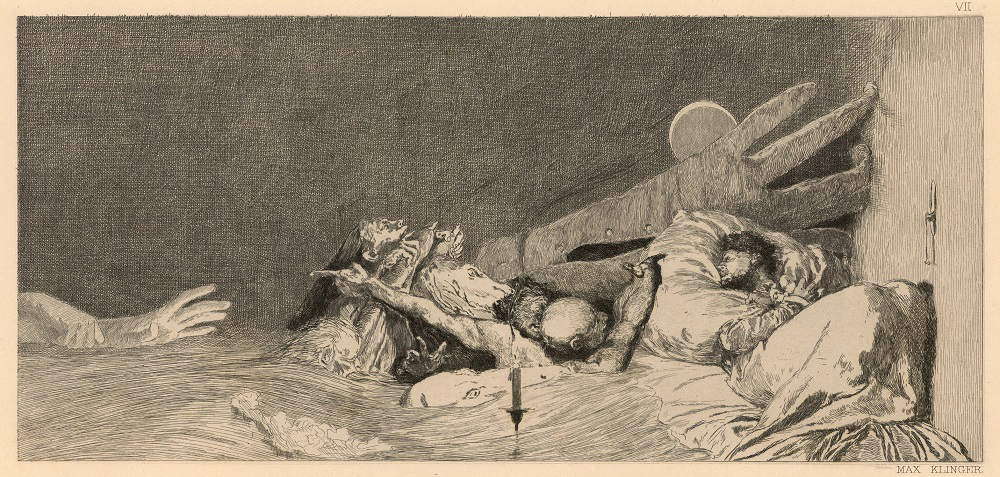

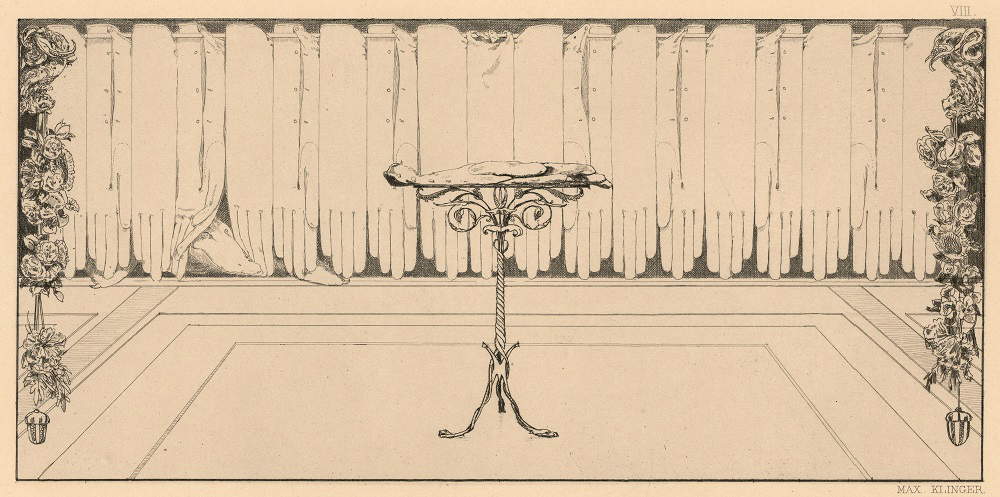

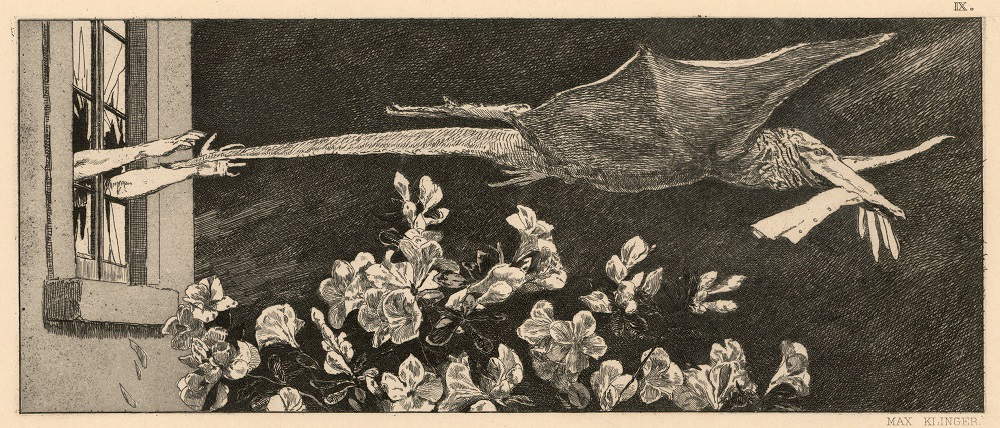

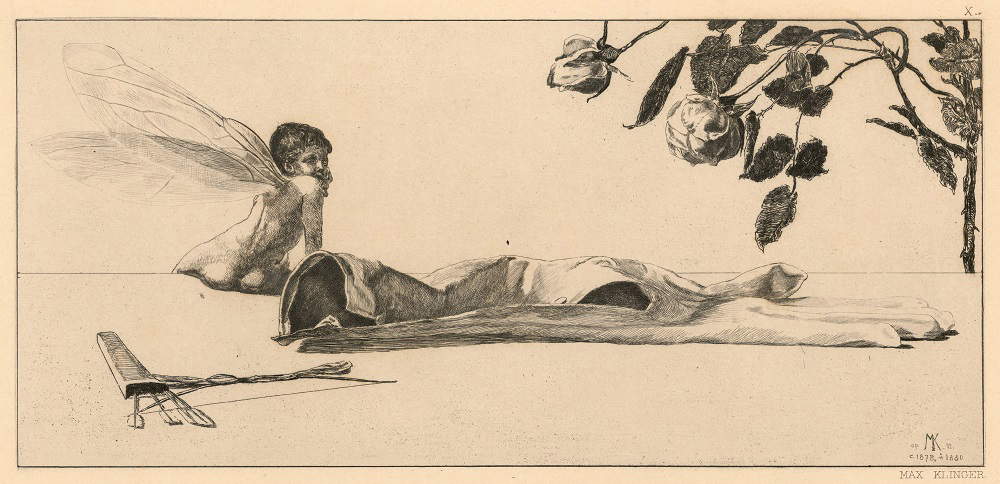

The protagonist of the story, told in ten etchings, is Max Klinger himself: A Glove is a kind of fantastic autobiographical tale that begins at a skating rink where the painter is on his way. In the first etching, titled Ort (“Place”), the artist is self-portraying in the company of his friend Hermann Prell: he is the man standing to the left, wearing a beard and dark coat. Klinger begins skating on the rink when a woman in front of him loses a glove: the artist bends down to pick it up, losing his hat (second engraving: Handlung, “Action”). From this moment, however, the glove, which the painter evidently fails to return to the lady (the reason for the failure to return is not made explicit, however), becomes a kind of fetish that guides Klinger on a hallucinatory journey through dreams and nightmares (third engraving: Wünsche, “Desires”): we see the scene of a storm, with a boat attempting to plough through the rough sea in an attempt to retrieve the glove from among the waves (fourth engraving: Rettung, “Rescue”), immediately followed by the scene of the glove alone driving a chariot that proceeds along the shore of a now calm and sunlit sea (fifth engraving: Triumph, “Triumph”), a sea that, moreover, even goes so far as to reverence the glove (sixth engraving: Huldigung, “Homage”). Meanwhile, the painter still struggles with nightmares, with strange creatures haunting him while he sleeps and the sea coming to lap the bed in his room (seventh engraving: �?ngste, “Fears”). Now, however, the glove is apparently safe, on a pedestal, surrounded by several other gloves (eighth engraving: Ruhe, “Quietness”), but the peace is destined to be short-lived, for before long a monstrous bird arrives and steals the glove (ninth engraving: Entführung, “Rat”). The vision ends with the god Love observing the glove lying on a flat surface (tenth engraving: Amor).

The series is a powerful and visionary narrative that speaks to the viewer of desire and loss: the glove, from being a fetish, becomes an animate object, endowed with a life of its own, causing torment to the painter from the earliest moments, for example when, in the third engraving, Klinger despairs in the bed of his room, his face in his hands, probably because his hesitation in returning the glove has separated him perhaps irretrievably from the woman (who in this first vision, with the room taking on the contours of a landscape, now appears very distant, tiny). That object so common thus becomes a kind of love allegory (in the Triumph one can read a kind of allegory of the goddess Venus, so much so that the very chariot carrying the glove is shaped like a shell: and according to Greek mythology, the goddess of love was born precisely from a shell) that attracts and subjugates him at the same time. Art historians John Kirk Train Varnedoe and Elizabeth Streicher, who have compiled one of the most substantial monographs on Klinger’s graphic art, have written that A Glove is a work of extraordinary modernity: in particular, the series “anticipates by several years the studies of Freud and Krafft-Ebing on sexual pathologies and perversions [...]. The glove itself seems conspicuously Freudian, since it is simultaneously phallic (in the fingers) and vaginal (due to the fact that it is a covering object, and even more so because it has open slits on its back).” There are many erotic sublimations encountered in the story: the beast that steals the glove can be interpreted as the man devoured by desire who forcefully takes the object of his passion, the glove that in the fifth engraving drives the chariot drawn by the sea horses shows an obvious vaginal form, and the same glove that, in the last scene, on the contrary takes on a phallic form (although inert, on the ground, with the god Love who, with unusual insect wings, turns his back on it: perhaps an allusion to death, or to the end of love, or to the fleetingness of falling in love?). And, as noted by Varnedoe and Streicher, there are also many elements that anticipate psychoanalysis: the inanimate objects coming to life, the natural dimensions of the objects themselves altering, the attempt to give structure to a dreamlike vision.

|

| Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh, Plate 1: Ort (“Place”) (1881; etching and aquatint, 257 x 347 mm) |

|

| Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh, Plate 2: Handlung (“Action”) (1881; etching, 299 x 210 mm) |

|

| Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh, Plate 3: Wünsche (“Desires”) (1881; etching and aquatint, 316 x 138 mm) |

|

| Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh, Plate 4: Rettung (“Rescue”) (1881; etching, 236 x 181 mm) |

|

| Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh, Plate 5: Triumph (“Triumph”) (1881; etching, 159 x 327 mm) |

|

| Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh, Plate 6: Huldigung (“Homage”) (1881; etching, 159 x 327 mm) |

|

| Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh, Plate 7: �?ngste (“Fears”) (1881; etching, 143 x 268 mm) |

|

| Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh, Plate 8: Ruhe (“Quietness”) (1881; etching, 143 x 267 mm) |

|

| Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh, Plate 9: Entführung (“Rat”) (1881; etching and aquatint, 119 x 269 mm) |

|

| Max Klinger, Ein Handschuh, Plate 10: Amor (1881; etching, 142 x 265 mm) |

Among the most enthusiastic admirers of the series dedicated to the glove was one of the greatest Italian artists of the early twentieth century, Giorgio De Chirico (Volos, 1888 - Rome, 1978), who reserved words of praise for it in a writing entitled Max Klinger, composed in 1920: "In the series of etchings entitled: Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove, Klinger to the romantic-modern sense adds a dreamer’s and storyteller’s fantasy, gloomy and infinitely melancholy. This series is an autobiographical piece, an account of an episode in his life.“ A meticulous description of the ten plates then followed: ”One evening, in a roller-skating hall, Klinger who is among the skaters finds a woman’s glove on the ground; he picks it up and holds it. It is the first engraving. On the find of this glove the artist weaves a fabulous tale of marvelous lyrical imagination. In the second etching, entitled The Dream, he is sitting in his bed with his face hidden in his hands. The glove lies laid on the night table by the lit candle, and in the background the wall has opened up like the scene of a theater and a distant, nostalgic spring landscape appears. In the other etchings, other visions follow. The spring landscape has turned into a sea swollen by the storm; the swells reach up to the bed and kidnap the glove, and here the dreamer dreams of being on the high seas, alone in a burchiello battered by the waves, and with a billhook anxiously tries to regain the glove floating on the foaming water. Then we see again the enlarged glove, which has become like a strange symbol of the mysterious and nagging love, rowing in triumph within a shell pulled by svelte sea horses, whose reins it holds clutching its long, hollow leather fingers. In the following etching, the glove is laid over a smooth rock erected like an ark by the sea. Large ancient lamps burn at the sides and the waves come in covered with roses pouring at the foot of the rock. But behold, the dream becomes harried and turns into a nightmare: the sea again invades the sleeper’s room; the cavalcades reach him; he turns full of breathlessness and anguish on the side of the wall, and on the waves, obscuring the moon descending to the horizon, appears the gigantic, swollen glove like a sail in which the storm blows; strange sea creatures rise from the water and gesticulate hostilely against the dreamer who wants to desecrate the beloved glove. But then the nightmare of the sea dissipates, and the sleeper sees the glove, restored to normal, laid on the table of an elegant store; behind the table a row of stiff, gigantic gloves, hanging from a bar, forms a kind of barrier and guard of honor. But lo and behold, between that barrier passes a monstrous bird that grabs the glove with its rostrum and flies out the window; the dreamer leaps from the bed and rushes, but the bird is already far away. In the last etching we see the epilogue of the fable. The dreamer has woken up: the glove is still laid on the small table, by the bed, and the love child approaches smiling, as if to say that everything was nothing but a bad dream."

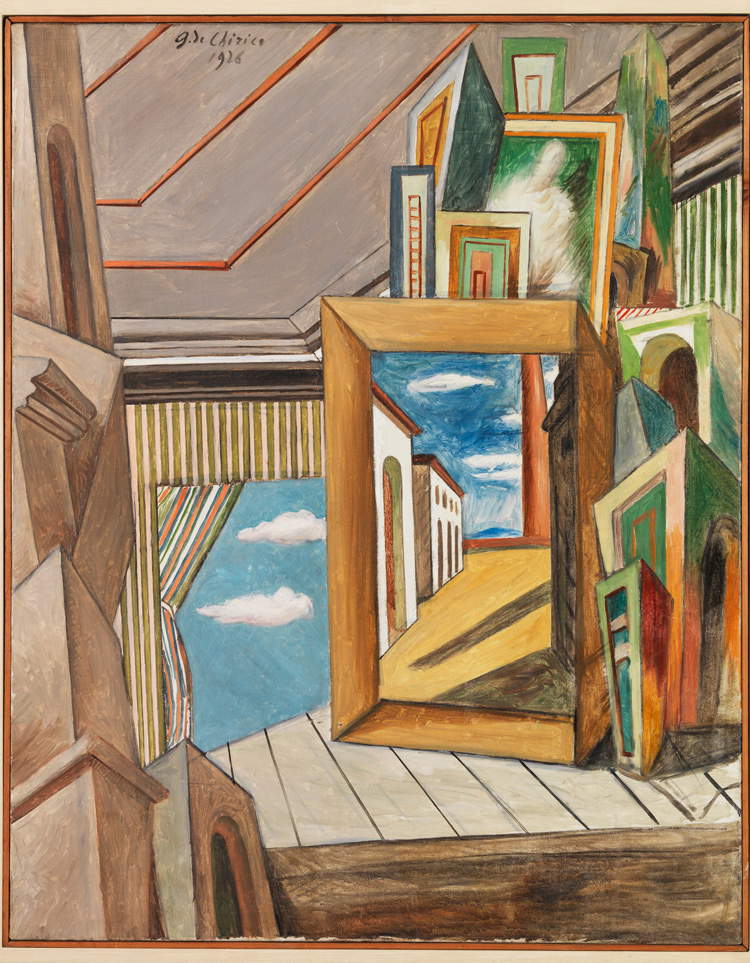

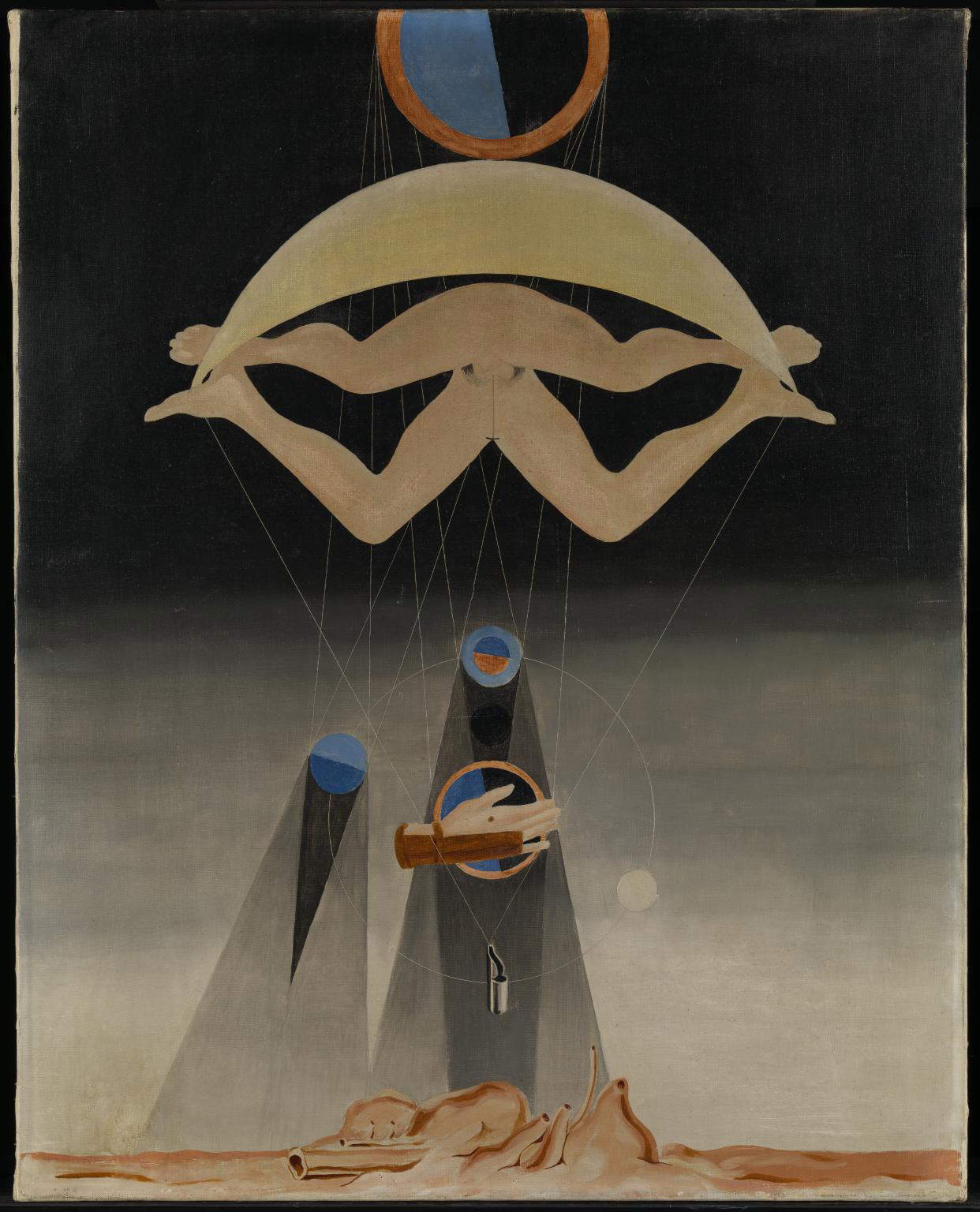

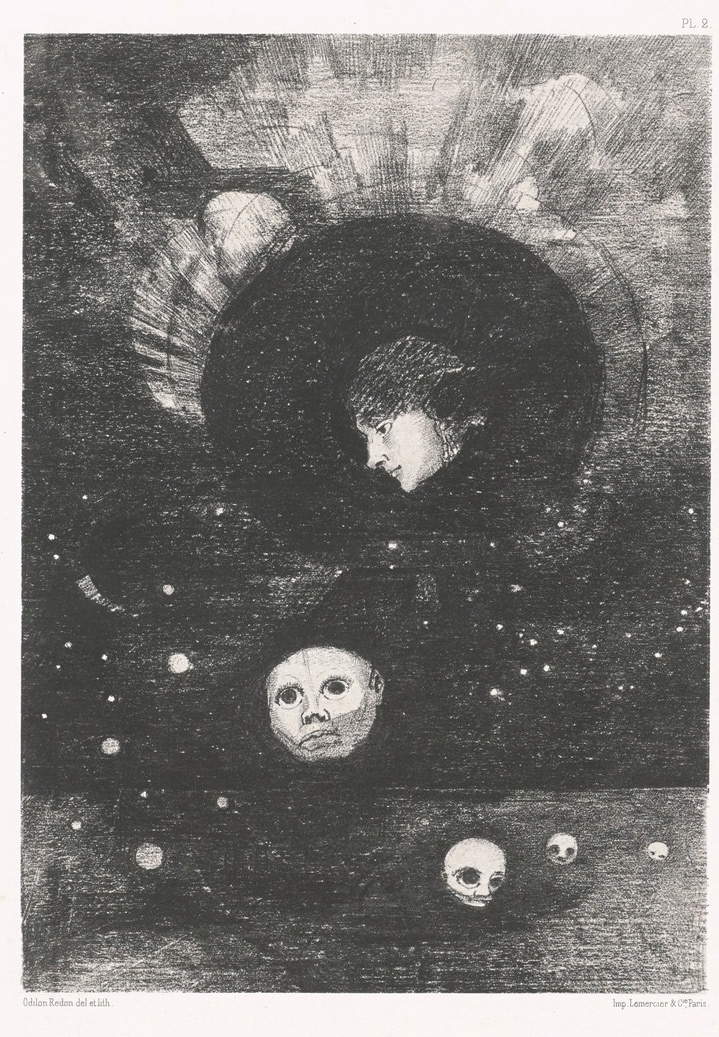

As is easy to see from De Chirico’s text, his focus is mainly on two plates, Wünsche (which the Volos artist translates as “The Dream”) and �?ngste, moreover the only two to which Klinger gives a plural title. Critic Adriano Altamira has noted how this focus, on De Chirico’s part, on these two etchings is probably a reflection of his interest in the theme of the room opening to the outside, which would become characteristic of De Chirico’s own art (particularly the Interiors that the painter would work on in the 1920s). Altamira also fits into the groove of those who believe that the same suggestions may have come to Max Ernst (Brühl, 1891 - Paris, 1976), who would rework them for the cellar scene featured in the film Dreams That Money Can Buy, a series of dream sequences devised by several Surrealist artists (but we also find the glove in Les hommes n’en sauront rien and in L’éléphant Célèbes). It has, after all, been noted that Surrealism owes several debts to Klinger’s fantastic visions: his ability to shape dreams could not fail to exert a certain fascination. Not least because Klinger’s research in this regard was pioneering: few artists before him had decided to make dream visions visible (Grandville in 1844 with Un autre monde, or Odilon Redon in 1879 with Dans le rêve).

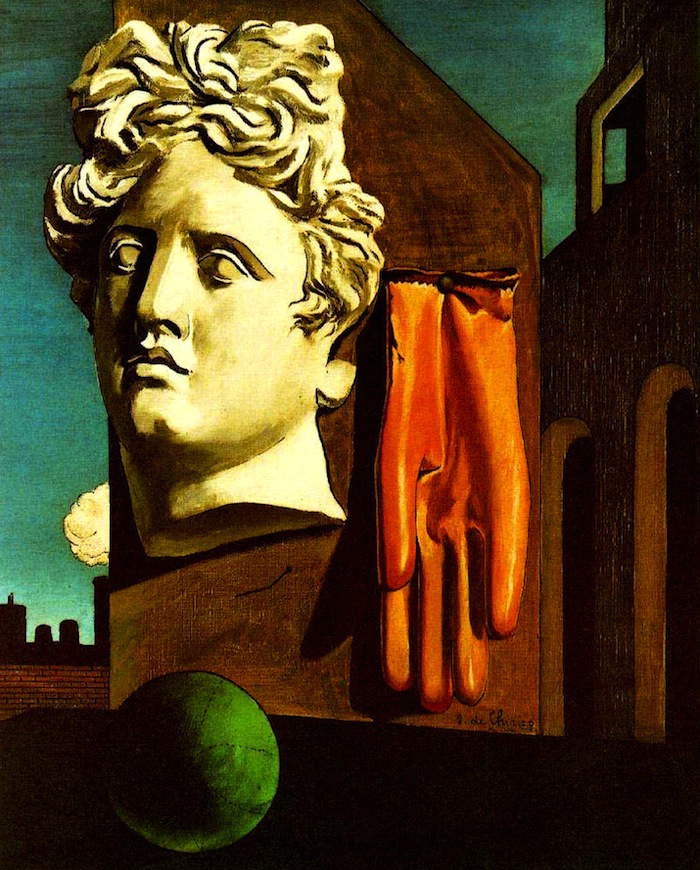

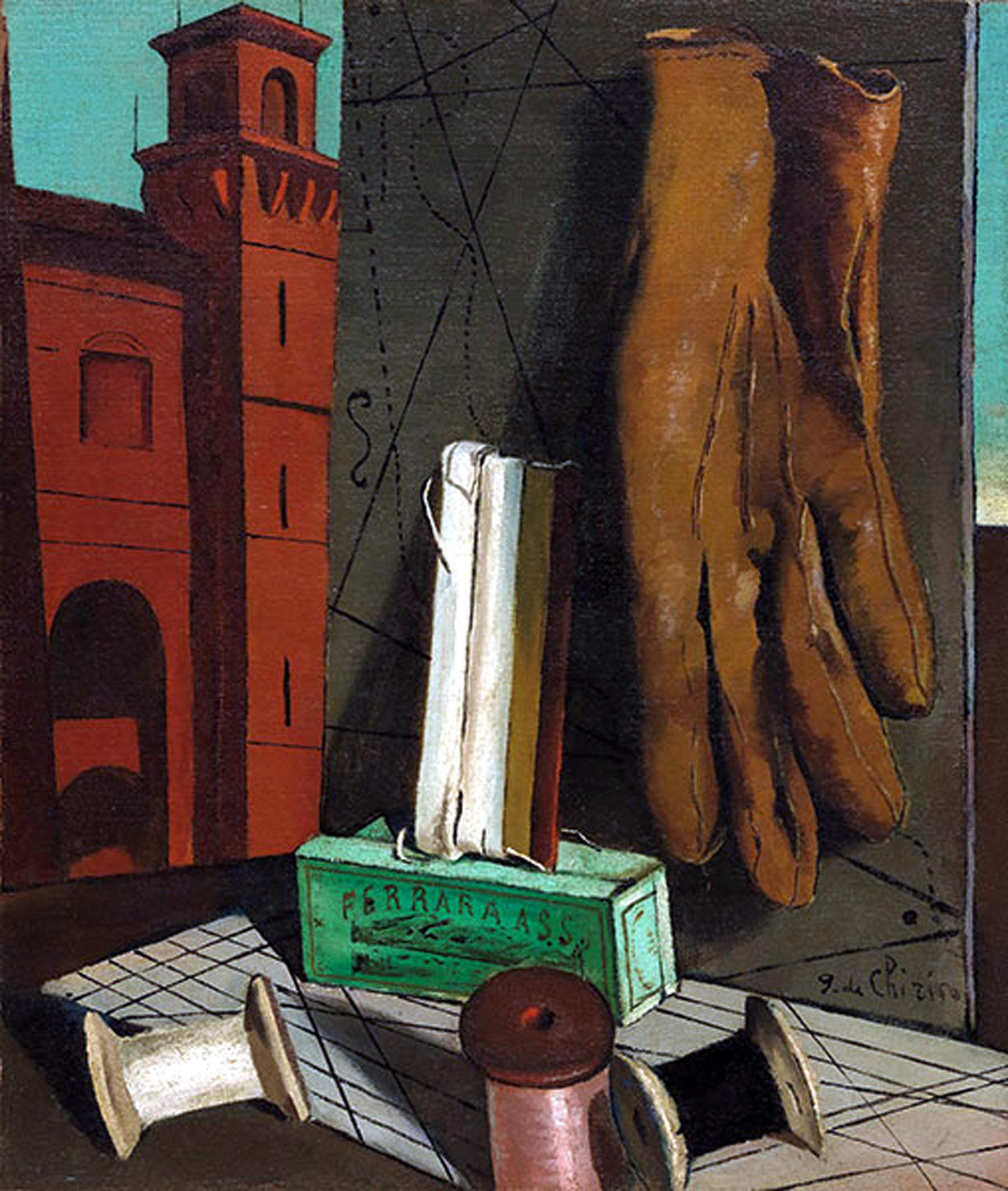

Again, De Chirico appreciated in Klinger his ability to be an interpreter at the same time of the “mythical-Hellenic sense” and the “romantic-modern sense.” The German artist was, for De Chirico, animated by a spirit that allowed him to attribute a real body to Greek myth: and however fantastic his visions were, Klinger was nonetheless “based on the foundation of a clear reality, powerfully felt,” De Chirico emphasized, which allowed him to avoid wandering into “delusions and obscure ravings.” Klinger’s originality lies in the fact that he understood his fantasies as juxtapositions of elements pertaining to different worlds, contrary to what happened, for example, in Redon, an artist who transports the relative into a universe that is already far removed from reality, with which he has lost almost all contact. Klinger, on the other hand, displaces the viewer with associations from different contexts, anticipating in some ways even Duchamp. And it is perhaps also on the basis of these suggestions that De Chirico describes Klinger’s “romantic-modern sense” as his ability to find the deepest aspects of romanticism even from the chaos of modern industrial society life, where by “romanticism” De Chirico meant a kind of sense of nostalgia that pervades European cities, a melancholy that envelops railway stations and seaports, the calm of a summer night. It is, in essence, a strong and deep, ancient and mysterious feeling that lurks in the folds of everyday life, and which will also find a correspondence in the works of De Chirico himself. The glove, then, would become the protagonist of his paintings: in I progetti della fanciulla we see it hanging on a wall in front of a series of objects and next to a reproduction of the Castello Estense in Ferrara (which together with Turin is for De Chirico the metaphysical city par excellence: the co-presence of ancient and modern, its esoteric history, its alchemical tradition) and in the 1914 Canto d’amore, the glove hangs on a wall next to a head of theApollo del Belvedere. By virtue of its evocative capacity (a glove is an object that belongs to someone, it is an object that is worn, it is an object that covers), the glove becomes a kind of metaphysical self-portrait of the artist (or an “absent self-portrait,” to use the effective expression of the aforementioned Altamira). Giorgio De Chirico’s brother, Alberto Savinio (Athens, 1891 - Rome, 1952), in theOration on the Roof of the House of his Hermaphrodite described a scene that has often been juxtaposed with the Song of Love in an attempt to interpret its meaning: “a little while ago, as I had returned to the sold room, I took off a glove and nailed it to the wall. The dangling glove retains the shape of the empty hand: I look in that corpse of a hand at my fate, which is no more than a deflated rind.”

|

| Giorgio De Chirico, Metaphysical Interior (1926; oil on canvas, 93 x 73 cm; Mart, Trento and Rovereto Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

|

| Max Ernst, Les hommes n’en sauront rien (1923; oil on canvas, 80.3 x 63.8 cm; London, Tate Modern) |

|

| Max Ernst, L’éléphant Célèbes (1921; oil on canvas, 125.4 x 107.9 cm; London, Tate Modern) |

|

| Odilon Redon, Germination, panel from the series Dans le rêve (1878; lithograph, 27.1 x 19.5 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Giorgio De Chirico, Song of Love (1914; oil on canvas, 73 x 59.1 cm; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Giorgio De Chirico, The Designs of the Maiden (1915; oil on canvas, 47.5 x 40.3 cm; New York, MoMA) |

Returning to Klinger’s series, it should be pointed out that originally, when the plates were exhibited in 1878 in Berlin in their ink version, the succession the artist had devised was different from the one he would decide on for the final redaction (the third plate was missing, Paure came third, Amor came next, the Rape scene was the third-to-last, immediately followed by the Quiet, and thus the conclusion was the Triumph). However, no matter how hard one tries to find a different interpretation for the order that Klinger initially established, there always emerges a “deliberately disjunctive” nature (so Varnedoe and Streicher) where scenes of calm and tranquility are alternated with images of anxiety and violence, and security is followed by visions filled with uncertainty: it seems that behind A Glove there is always something elusive. The medium of black-and-white printing is, moreover, instrumental in emphasizing the eminently visionary character of the series: in his essay Malerei und Zeichnung (“Painting and Drawing”), Klinger wrote clearly that color works, out of all paintings, are apt to represent the natural and to render objects as we see them in reality. In contrast, black-and-white works (drawings and prints: for Klinger, Zeichnung also includes print production) are considered suitable for shaping everything that is fantasy and imagination. And perhaps this is also why we especially remember Klinger’s prints: because in graphic production he set no limits for himself and managed to be extraordinarily modern and much more original than in painted production. Art historian Beatrice Buscaroli, in pointing out the modernity of Klinger’s masterpiece, speculated that the artist probably did not know any psychological texts: his visions, the scholar believed, accord, if anything, with the Zeitgeist of the time, common to other great artists who, like Klinger, were among the first to provide representations of the dreamlike universe (Odilon Redon, Ferdinand Hodler, Arnold Böcklin). Those estranging juxtapositions between elements of the real world and elements produced by the imagination would later become, as anticipated, the subject of study of psychoanalysis: and in this regard it is interesting, Buscaroli continued, “to note how the natural fusion of fiction and reality, of invented creatures and real landscapes, pursued by Böcklin, before Klinger, had become, for the father of psychoanalysis, a kind of symbol, personal and general, to be cited in a scientific text, as in private letters.”

After the success of A Glove, Klinger would continue to focus on the technique of printing, not only as a means of giving substance to his fantasies, but also as a tool for investigating reality (by way of example, a series such as Ein Leben, “A Life,” which deals with the drama of a woman humiliated and ruined by bourgeois society). And we can safely say that his prints, which continued to have a wide circulation, helped guide certain developments in 20th-century art.

Reference bibliography

- Marsha Morton, Max Klinger and Wilhelmine culture: on the threshold of German Modernism, Routledge, 2014

- Adriano Baccilieri (ed.), Giorgio de Chirico and the Sign, exhibition catalog (Civitanova Marche, Auditorium Sant’Agostino, July 13 to November 9, 2008), Bora, 2008

- Adriano Altamira, De Chirico, Böcklin and Klinger in Metaphysics. Quaderni della Fondazione Giorgio e Isa de Chirico, 5/6 (2005-2006), pp. 35-64

- Adriano Altamira, Romantic myths: symbols and the unconscious of the industrial age, Vita e Pensiero, 2004

- Beatrice Buscaroli (ed.), Max Klinger, exhibition catalog (Ferrara, Palazzo dei Diamanti, March 17 to June 16, 1996), Ferrara Arte, 1996

- Beatrice Buscaroli, Max Klinger, 1996

- John Train Kirk Varnedoe, Elizabeth Streicher, Graphic works of Max Klinger, Dover Publications, 1977

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati

Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da

Federico Giannini e

Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato

Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009.

Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamo

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.