by Ilaria Baratta, published on 03/10/2019

Categories:

Works and artists

- Quaderni di viaggio / Disclaimer

How Peggy Guggenheim's collection was born and developed, what her interests were, what artists she dialogued with.

“It has always been taken for granted that Venice is the ideal city for a honeymoon, but this is a serious mistake. To come to Venice, or simply to visit it, is to fall in love with it, and in the heart there is no room left for anything else,” so reads a passage in A Life for Art, the autobiography of Peggy Guggenheim (New York, 1898 - Camposampiero, 1979 ) published in 1979, the year of her death. And certainly Peggy knew that feeling very well: a corresponding bond with her adopted city, in which she spent the last thirty years of her life, from 1949 to 1979.

By the time she arrived in the lagoon, Peggy was already well known in the contemporary art world as a gallery owner and collector: in fact, her career in this sphere began in 1938, when she was only thirty-nine, with the opening of her first art gallery in London, to which she gave the name Guggenheim Jeune; her friendships also belonged fully to the art world: consider that she had already befriended Brancusi, Duchamp, and the writer Samuel Beckett, all of whom incited her to devote herself tocontemporary art because it was a “living thing,” and helped her fit more and more into that environment. After the London experience and buying according to her intentions one painting a day to enrich her collection, she opened another gallery in New York in 1942, choosing to name it Art of This Century. Similarly, in the United States she surrounded herself with artists, also hitherto unknown, to whom she devoted temporary exhibitions, including Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell and Jackson Pollock; in particular, she actively promoted the latter, selling his works and dedicating the gallery’s first solo show to him in late 1943. And it was thanks to Peggy that Jackson Pollock (Cody, 1912 - Long Island, 1956) himself was able to exhibit his creations in Europe for the first time, precisely at the 1948 Venice Biennale, in which she participated by bringing masterpieces from his collection to the Greek pavilion. This experience made her fall in love with the city of Venice, so much so that she decided to move among gondolas and canals in 1949 with her complete collection, purchasing the splendid Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, where The Peggy Guggenheim Collection can still be visited today. Designed by the architect Lorenzo Boschetti, the palace was begun to be built in 1748, but for reasons that are still unclear it remained unfinished; nevertheless of its uniqueness and brightness Peggy Guggenheim was enchanted, and indeed to this day its stained glass windows and its terrace directly on the canal make it one of the most striking palaces in Venice.

It is from these assumptions that today’s gallery-museum planned to mount a tribute exhibition that tells the Venetian story of Peggy Guggenheim and her post-1948 collection, that is, from the closing of the New York gallery Art of This Century and its move to Venice until the patron’s passing in 1979. A 30-year period that saw a succession of exhibitions, events, and acquaintances that influenced Peggy’s personal bond with Venice, but also Peggy’s vision in the art world both as a woman and as a collector. It is no coincidence that the title of the exhibition, which can be visited by the public until January 27, 2020, was chosen as Peggy Guggenheim. The Last Dogaressa, underscoring the prominent role she exercised in those years in the lagoon and still making her legacy as an icon perceptible today.

|

| Peggy Guggenheim in the garden of Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, Venice, 1950s. Behind her is Karel Appel, The Crying Crocodile Tries to Catch the Sun, 1956. Photo Roloff Beny / courtesy of Archives and National Archives of Canada. |

|

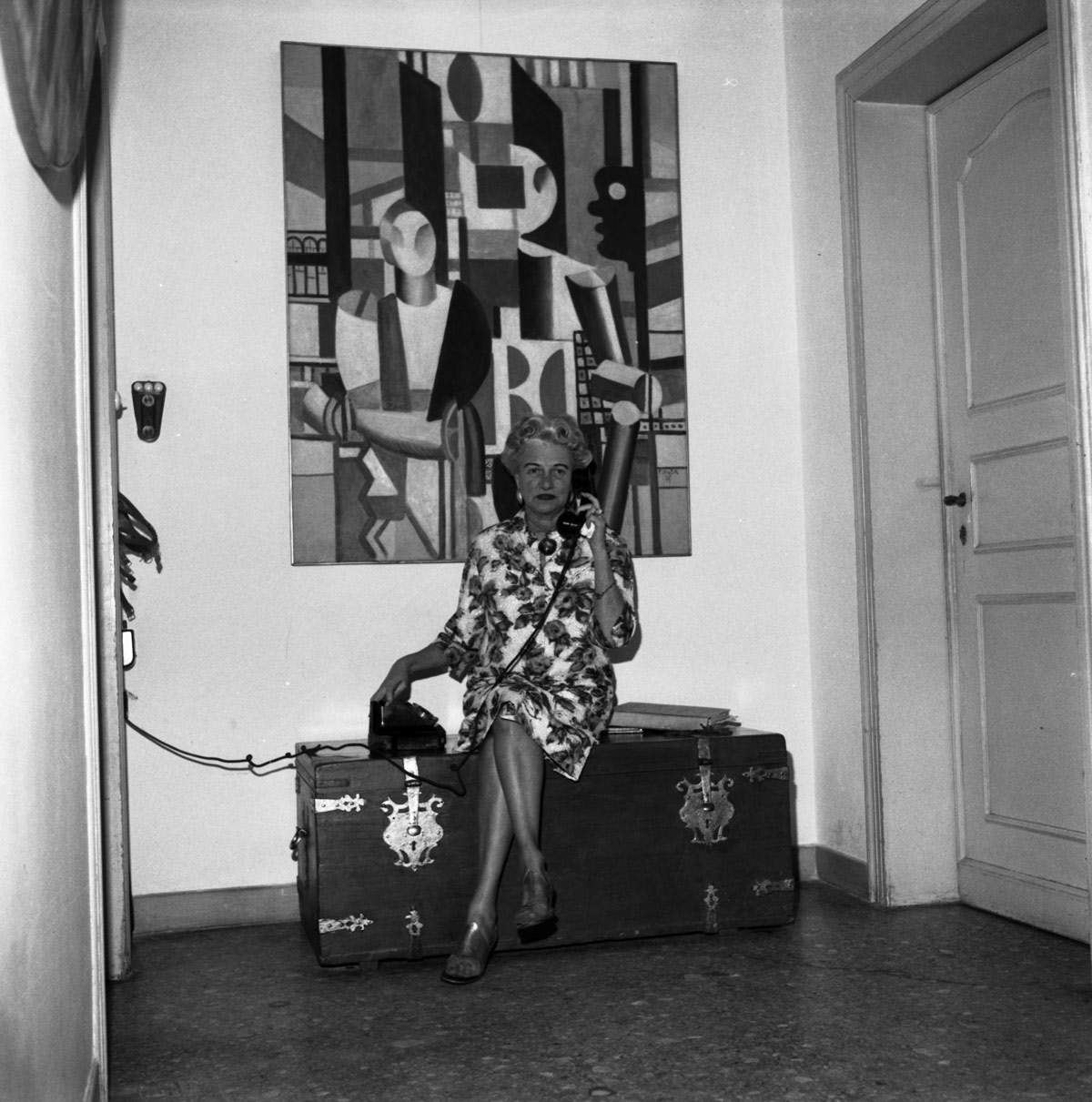

| Peggy Guggenheim at Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, Venice, early 1960s. Behind her is Fernand Léger, Men in the City (Les Hommes dans la ville), 1919. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Photo Archive Cameraphoto Epoche. Donation, Cassa di Risparmio di Venezia, 2005. |

|

| Peggy Guggenheim with her terrier Lhasa Apsos on the terrace of Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, Venice, late 1960s. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Photo Archive Cameraphoto Epoche. Donation, Cassa di Risparmio di Venezia, 2005. |

|

| Peggy Guggenheim at the entrance to Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, Venice, 1967. Courtesy The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation |

|

| Peggy Guggenheim in a gondola, Venice, 1968. Photo Tony Vaccaro / Tony Vaccaro Archives |

|

| Peggy Guggenheim seated on throne in the garden of Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, Venice, 1960s. Photo Roloff Beny / courtesy of Archives and National Archives of Canada |

|

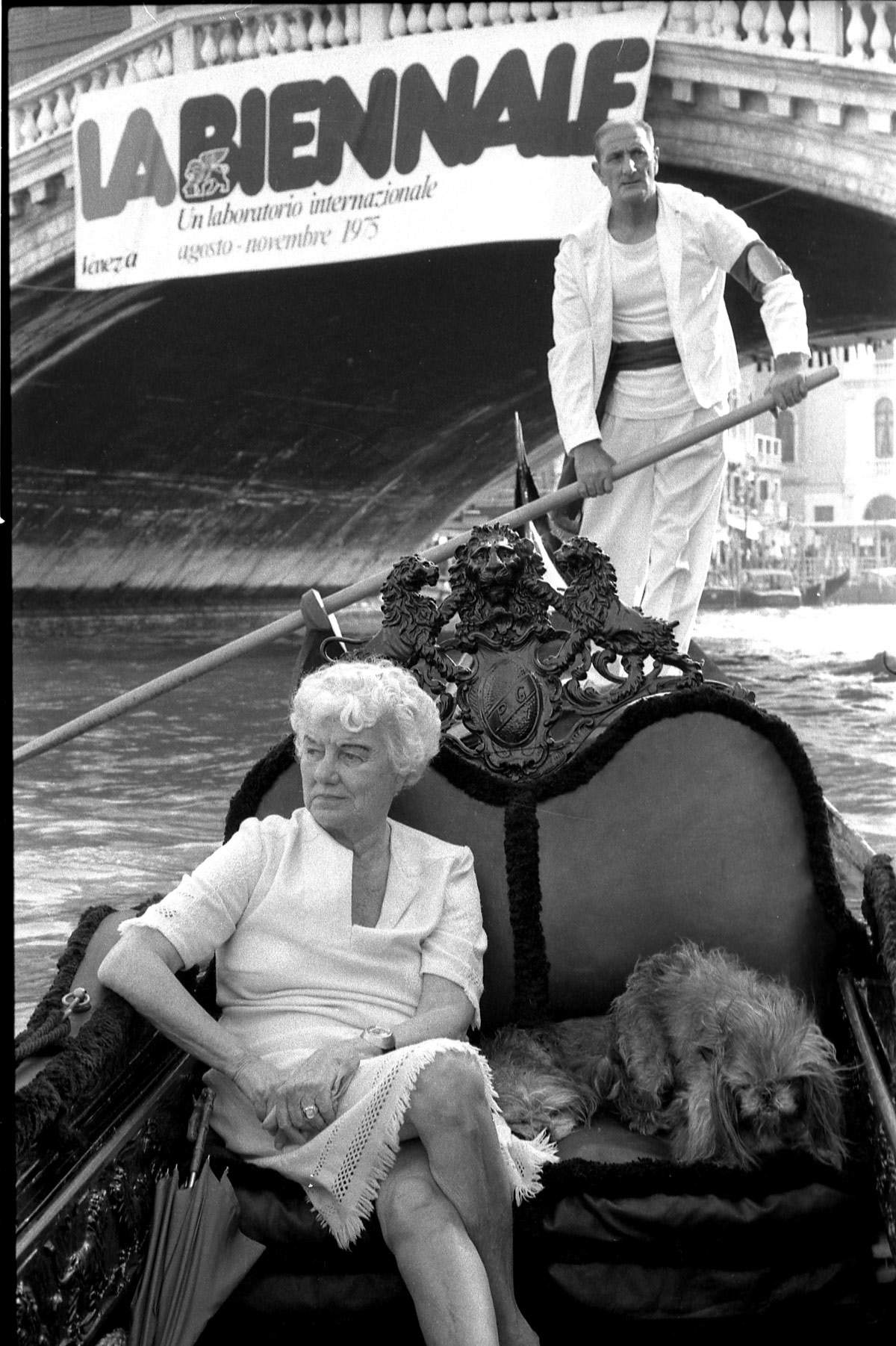

| Peggy Guggenheim in a gondola on the Grand Canal, Venice, 1975. © Gianfranco Tagliapietra Interpress Photo. |

|

| Peggy Guggenheim at the Gritti Palace on the occasion of her 80th birthday party, Venice, August 26, 1978. © Gianfranco Tagliapietra Interpress Photo. |

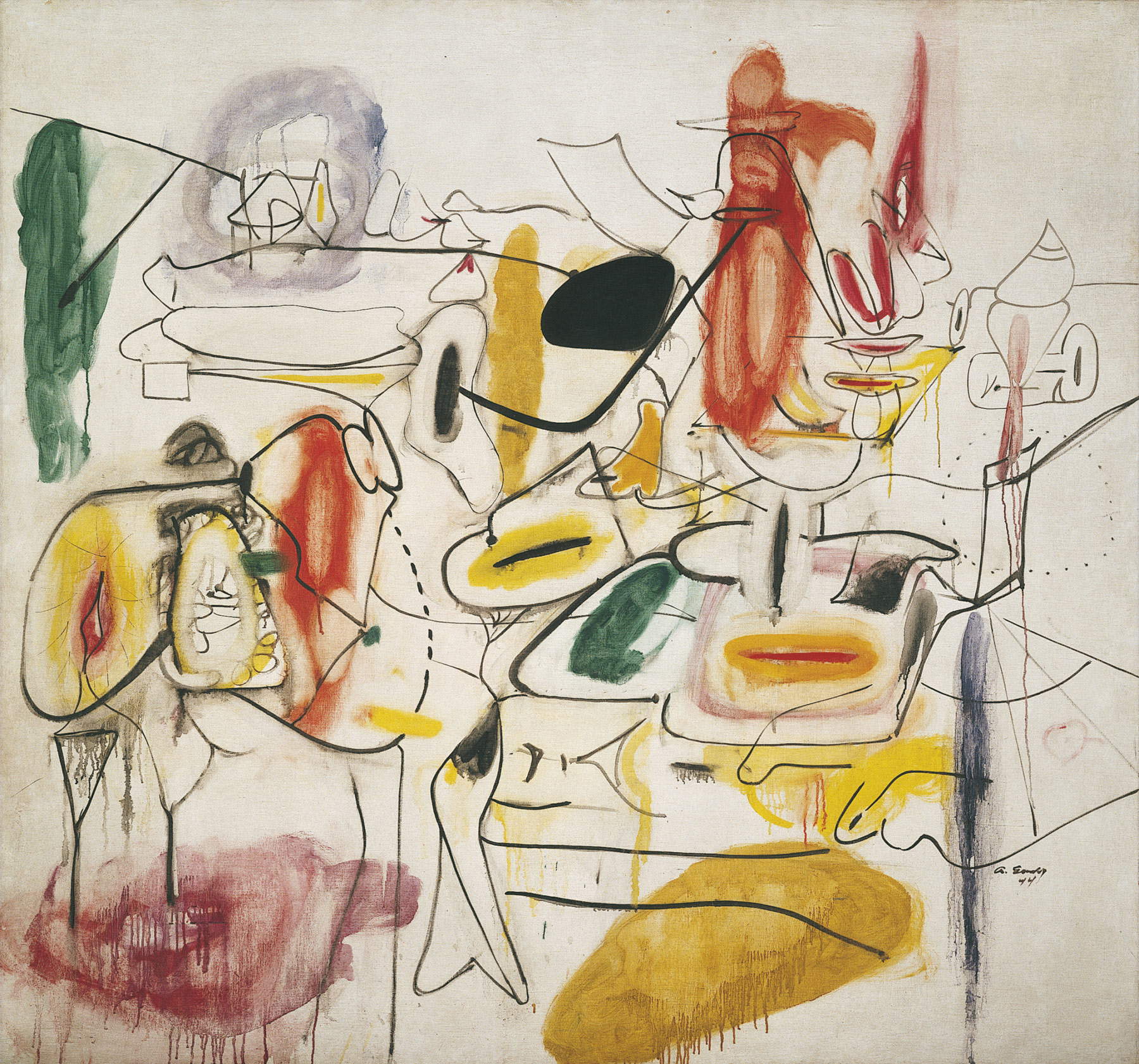

As already stated, the bond of mutual esteem between Peggy and Pollock prior to their move to Venice resulted in the 1948 Biennale, at which the collector was able to make her name known in the lagoon, setting up the first rich and extensive survey of modern art in Italy after the regime, and Jackson Pollock made his European debut. An exhibition, the artist’s first solo show outside the United States, was dedicated to the latter two years later, with twenty-three works in theNapoleonic Wing of the Correr Museum, among which he also exhibited ten of his colatura paintings. The Last Dogaressa takes its starting point precisely from works by the American artist, including The Moon Woman and Alchemy made between 1942 and 1947. The latter in particular was among the earliest executed using the dripping technique: primitive marks made by squeezing white color directly from the tube are spread unevenly across the canvas. However, although Pollock was the most striking case, it must be remembered that in the 1948 Biennial other American painters were presented on the European scene, such as Mark Rothko (Daugavpils, 1903 - New York, 1970), Robert Motherwell (Aberdeen, 1915 - Provincetown, 1991), Arshile Gorky (Khorkom, 1904 - Sherman, 1948) and Clyfford Still (Grandin, 1904 - Baltimore, 1980), who were also present with works from that period at today’s Venetian exhibition.

In September 1949, by which time Peggy had already become a Venetian citizen, she decided to open the garden of her new home to the public, and she did so with another mundane event: the Exhibition of Contemporary Sculpture, through which she planned to present acquisitions from her collection that were intended to concretize the various languages of modern sculpture and make manifest her interest in the European avant-garde. Twenty sculptures by Jean Arp (Strasbourg, 1887 - Basel, 1966), Constantin Brancusi (Pestisani, 1876 - Paris, 1957), Alberto Giacometti (Borgonovo di Stampa, 1901 - Chur, 1966) and other exponents of the twentieth century were therefore exhibited: among them, Arp’s Head and Shell, the first work to enter the Guggenheim collection in 1938 and a small masterpiece among the most significant pieces featured in the recent retrospective devoted to the Strasbourg artist; Brancusi’s Bird in Space , where the idea of flight is represented by an aerodynamic form in polished brass, and Giacometti’s Piazza , a bronze work in which five slender figures seem to walk on a large square without ever meeting to signify how everyone lives their individuality without giving importance to sociality and community.

With her move to Venice, Peggy also fully participated inItalian art, supporting a number of local Italian artists and buying their works: among them was Emilio Vedova (Venice, 1919 - 2006), who since after World War II had begun to devote himself toabstract andInformalart. His is Image of Time (Barring), egg tempera on canvas in which black dominates with splashes of red and yellow, through which the artist expresses themes of the era in which he lives in a manner similar to the American Pollock. In addition, the collector helped to popularize the art of exponents of Spatialism, such as Edmondo Bacci (Venice, 1913 - 1978), who in his Avvenimento #247, an oil with sand on canvas from 1956, depicts the origins of matter in extraterrestrial regions; blue, red and yellow colored forms spring from a cosmic eruption and are themselves preparing to generate life. Abstract colored forms also feature prominently in Above the White, a 1960 work by Japanese artist Kenzo Okada (Yokohama, 1902 - Tokyo, 1982), an exponent of thelyrical abstractionism typical of Japan, where the so-called landscape of the mind is represented.

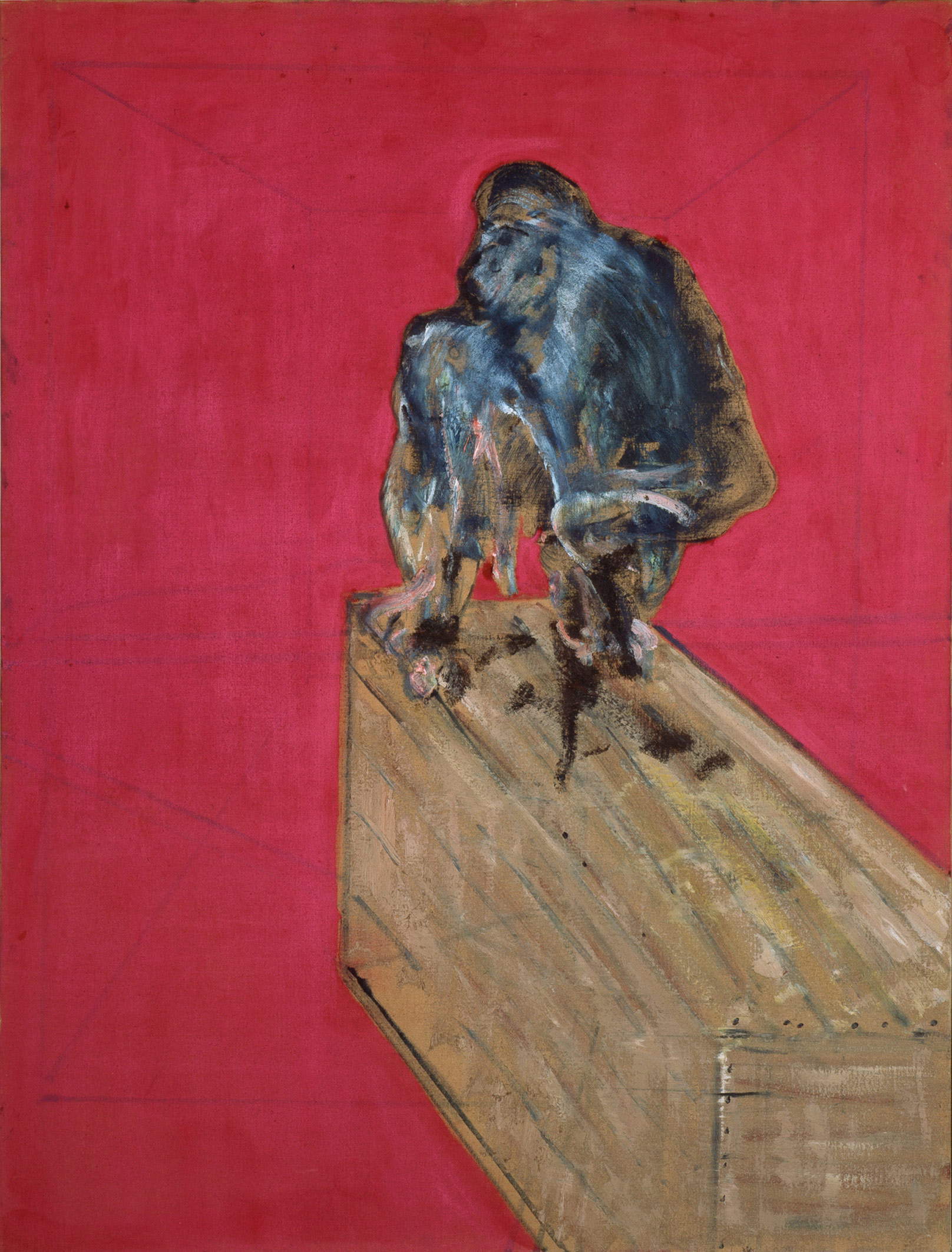

The other categories, if they can be so defined, in which Peggy Guggenheim had a certain interest and desire to possess in her gradually growing collection areBritish art andoptical and kinetic art. To the former belong paintings characterized by a monochrome background on which figures are depicted and become protagonists: Examples are Francis Bacon ’s Study for Chimpanzee (Dublin, 1909 - Madrid, 1992), where precisely a chimpanzee with deformed features is portrayed almost as if in a snapshot against a red background, and Graham Sutherland’s Organic Form (London, 1903 - Menton, 1980), where against a green background a shape resembling an altar stands out. Similarly, British sculptors were characterized by a predilection for the human and animal figure and in many cases by an abandonment of the traditional method of bronze casting to adopt forging and welding. These artists include Kenneth Armitage (Leeds, 1916 - London, 2002), Reg Butler (Buntingford 1913 - Berkhamsted, 1981), who were widely appreciated at the 1952 Venice Biennale, and Henry Moore (Castleford, 1898 - Much Hadham, 1986). By Armitage is the peculiar sculpture People in the Wind: a group of bronze figures in abstract forms that with their arms outstretched upward express an upward movement; by contrast, of more stylized forms is Woman Walking by Reg Butler. Henry Moore represents a family group with more rounded forms and the material appears more solid, while in Lying Figure, a polished bronze sculpture, the forms become more sinuous in a free creative act.

Case in point is the entry into the Guggenheim collection of The Empire of Light by René Magritte (Lessines, 1898 - Brussels, 1967) executed between 1953 and 1954: the canvas depicts a dark street illuminated only by the faint light of a streetlamp placed in front of a house; in the foreground a tall tree partially covers the house and the cloud-sprinkled sky is blue and clear. Thus day and night coexist in this painting, a coexistence that provokes disquiet, as is moreover typical of Surrealism to which the work belongs. There are other examples ofEmpire of Light kept in New York and Brussels.

If Emilio Vedova expressed in his paintings the anxieties of his time, in the 1950s and 1960s the artists of the CoBrA group, whose name came from the initials of the cities of its founders, namely Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam, reacted with an instinctive and revolutionary style to the tragedies of war. It was a style that remained so even after the group’s activity ended, lasting only three years, from 1948, as can be seen in The Weeping Crocodile Tries to Grab the Sun by Dutchman Karel Appel (Amsterdam, 1921 - Zurich, 2006), one of the founders of the CoBrA group: the crocodile is painted in thick colors applied frantically and bordered by black lines; what stands out is the strong color contrast given by very bold tones. A key characteristic is the spontaneity in the way of painting like that of children, without any attention to perspective and proportion. The same thick color on the canvas and the black lines of the outlines of the figures are found in Untitled by the Dane Asger Jorn (Vejrum, 1914 - Aarhus, 1973), another founder of the group: here the shapes of the figures depicted are hardly distinguishable in the overall environment, but a smiling standing human figure can be seen on the right and a bird in the center; around it various faces blend into the background. Colors become more muted in the artist than in Appel: light blues, light yellows, greens, and pinks combine with each other in harmony.

|

| Jackson Pollock, Circumcision (January 1946; oil on canvas, 142.3 x 168 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New |

|

| Jackson Pollock, The Moon Woman (1942; oil on canvas, 175.2 x 109.3 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New |

|

| Jackson Pollock, Eyes in the Heat (1946; oil-and enamel? - on canvas, 137.2 x 109.2 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New |

|

| Arshile Gorky, Untitled (summer 1944; oil on canvas, 167 x 178.2 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) |

|

| Emilio Vedova, Image of Time (Barring) (1951; egg tempera on canvas, 130.5 x 170.4 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection). © Emilio and Annabianca Vedova Foundation |

|

| Kenzo Okada, Above White (1960; oil on canvas, 127.3 x 96.7 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) |

|

| Francis Bacon, Study for Chimpanzee (March 1957; oil and pastel on canvas, 152.4 x 117 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, by SIAE 2019 |

|

| René Magritte, Limpero della luce (LEmpire des lumières) (195354; oil on canvas, 195.4 x 131.2 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) © René Magritte, by SIAE 2019 |

|

| Pierre Alechinsky, Robe (1972; acrylic on paper mounted on canvas, 99.5 x 153.5 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) © Pierre Alechinsky, by SIAE 2019 |

|

| Asger Jorn, Untitled (195657; oil on canvas, 141 x 110.1 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) © Donation Jorn, Silkeborg, by SIAE 2019 |

|

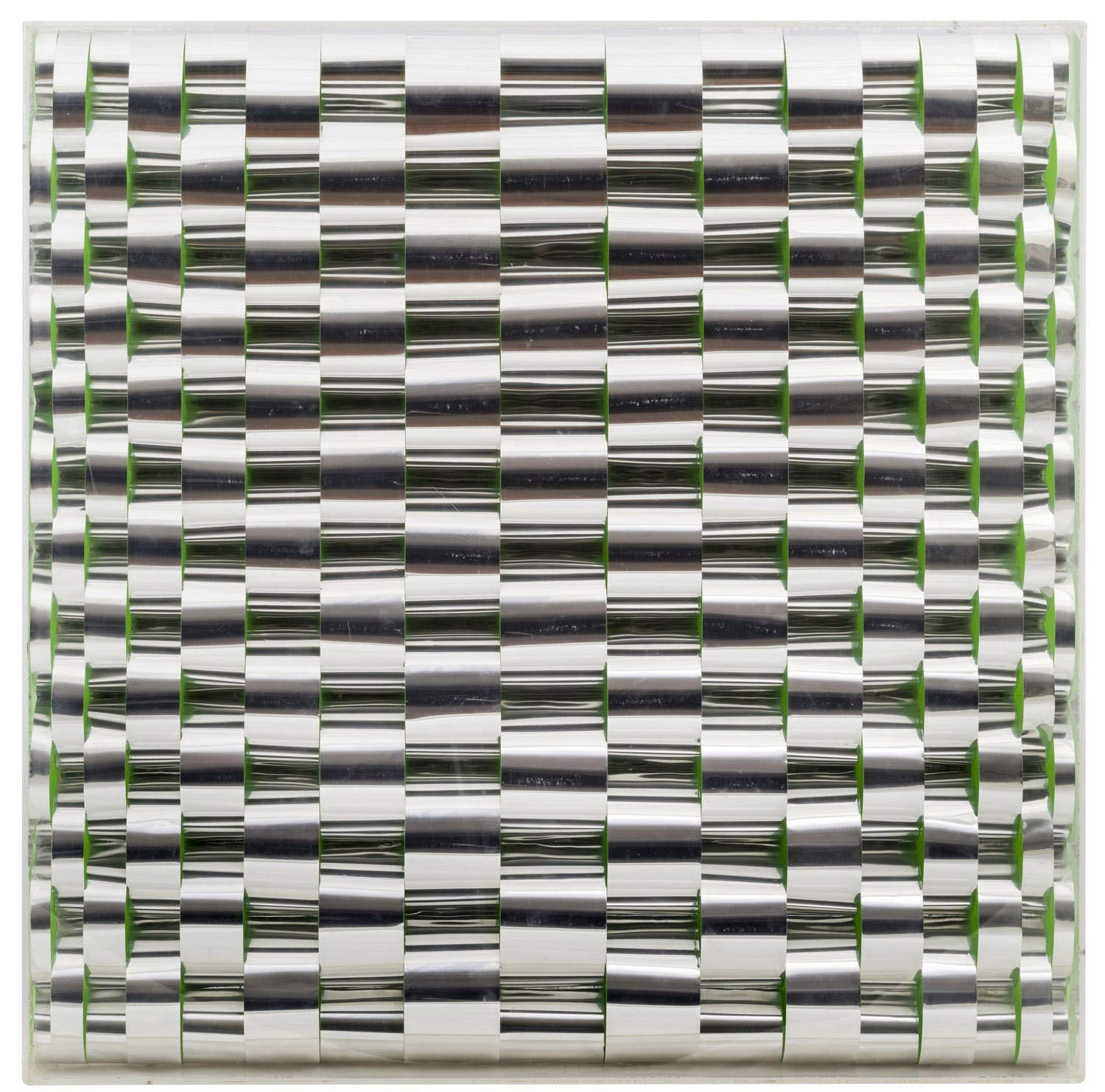

| Marina Apollonio, Relief No. 505 (c. 1968; aluminum and fluorescent paint on Masonite, 49.9 x 49.8 cm; Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection) |

Perfectly attuned to the contemporary era, Peggy began collecting works of Op art, theoptical and kineticart, in the 1960s. Illusory black and white geometries and peculiar optical effects dominated the art and fashion scene; reflections and transparencies helped alter the perception of shapes and objects, thanks also to the use of unusual materials drawn from the industrial world, such as aluminum, plastic, and glass.

In the wake of this modern trend, Peggy surrounded herself with works in Plexiglas, aluminum, and PVC, such as Optical Structure by Argentine Martha Boto (Buenos Aires, 1925 - Paris, 2004), a play on geometric figures, in this case circles, that exploiting the illusion of movement and reflective surfaces makes space undefined; Calvino’s Joy by the German Heinz Mack (Lollar, 1931), founder in 1957-58 of the Zero Group, which set out to reset past experiences, moving away from traditional painting and sculpture by creating object paintings and assemblages, fitting fully into German kinetic-visual research. And again, JAK by the Franco-Hungarian Victor Vasarely (Pécs, 1906 - Paris, 1997), where his graphic researches with geometric shapes, small rhombuses, and the illusory effect of light in the center of the work are exalted. Italian exponents of kinetic art who created interest in the American patron include Franco Costalonga (Venice, 1933 -2019) and Marina Apollonio (Trieste, 1940): the former’s peculiar Sphere in Plexiglas and chrome-plated metal is one of his most intriguing and evocative sculpture-works; the artist has declined one of his favorite subjects in numerous variations, transparent, reflective and colored, playing a lot with three-dimensionality. Marina Apollonio, on the other hand, in Rilievo No. 505, a work in aluminum and fluorescent paint on masonite, focuses on metal reliefs with elementary alternating color sequences, exploiting industrial materials.

Thanks to this succession of works that are part of the Peggy Guggenheim collection, one further understands how passion, strong devotion in art and the desire to make a healthy contribution to especially emerging exponents have been determining factors in the continuation and growth of a collection that was already significant in New York, but reached its zenith in Venice.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.