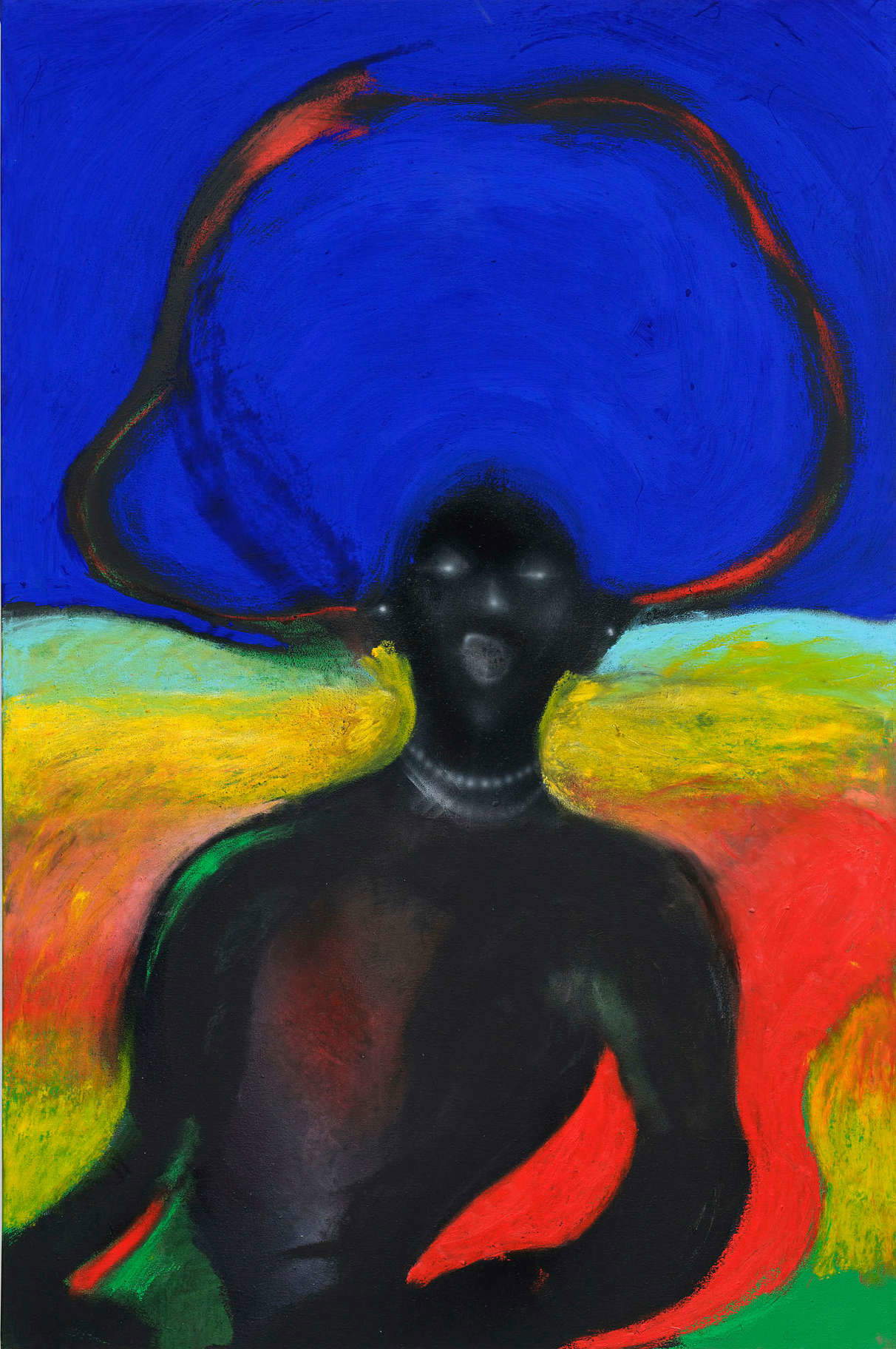

“Once upon a time” a painting that did not want to reassure. A painting that scratched, that whispered through mute faces and animal paws, a painting that hid behind veils of color and allusions, as if each canvas were the thin curtain between a world we know and one we refuse to name. In that theater of the ambiguous, moves Pol Taburet, a French-Guadalupese painter, born in 1997, one of the most dissonant and magnetic voices on the contemporary European scene.

Entering his visual universe is not a neutral gesture. It is an invocation. It is like crossing a ritual threshold, where logic dissolves and the skin becomes sensitive to unspoken meanings. His figures, elongated, angular, sometimes zoomorphic, sometimes hybrid, seem to come from a lucid dream or a mediumistic séance. But a dream of whom? Whose are these creatures with empty eyes and deformed postures, suspended in a time that is neither past nor future ?

Perhaps this is precisely the obsession that runs through all of Taburet’s painting: suspension. His characters always seem to be waiting for something, for a word, a gesture, a sentence. In works like Mud Field (2023), faces are embedded in walls, fused with architecture as if they were ghosts inhabiting the interstices of reality. In My Dear (2023), a set table, domesticity par excellence, becomes a scene of silent menace: the paws of an animal appear from under the tablecloth, suggesting a hidden presence, a looming violence. Who is the host, and who is the predator, in these theaters of power and illusion?

Taburet does not plan his paintings. His painting process is visceral, jazzy, built onimprovisation. He works directly on canvas with acrylics, alcohol pigments, airbrush, an aesthetic reference to hip hop culture and the personalization of bodies and objects, and finally, in some details, oil: there where the material becomes flesh, the instrument becomes slower, more ancient. This layering of techniques produces a fluid, iridescent painting that never seems to want to settle. Nothing is still in his paintings: even when everything is still, something vibrates.

In his recent exhibition Oh, If Only I Could Listen (2025, Madrid, Pabellón de los Hexágonos), the viewer is immersed in a landscape of silent tension. The canvases appear as broken icons, deconsecrated altars, where the sacred is present only as an uneasy echo. In an untitled work exhibited there, two figures face each other in a dark, undefined, almost liquid space. Their bodies are translucent, evanescent, but their gazes are fixed, not looking at each other, looking at us. And then the question becomes urgent: who is the subject, and who is the object, in this relationship? Are we the ones observing, or are we being observed?

There is in Taburet a narrative force that eschews storytelling. His canvases do not explain, do not lead, do not illustrate. Yet, they do tell. They tell of the fear of identity, of transformation, of time that corrupts and makes monstrous. His figures recall Antilles carnival masks, voodoo spirits, Ku Klux Klan hoods, ambivalent, ambiguous symbols between ritual and violence, between ancestral culture and historical nightmare. Indeed, these elements appear in many works: hooded faces, disguised bodies, pointed hats that recall penitential processions as much as racial supremacists. Where then is the line between sacred and profane? Where does the disguise begin, and where does the trauma end?

The hues used by Taburet, deep blacks, pulsing reds, electric greens, acid yellows, seem to exude a compressed energy, a charge that can explode at any moment. And one feeling in particular accompanies the observation of one of his paintings: bewilderment. One finds oneself disarmed, forced to be silent before something we cannot name. There is no catharsis. There is no solution. Only the possibility of being in the company of an enigma.

This is perhaps the most powerful legacy of Pol Taburet’s work: the restoration to painting of an oracular power. In a time dominated by the urgency of meaning, by the speed of communication, he forces us to slow down, to pause in doubt. His works are not meant to convince, but to evoke. They do not tell the world as it is, but as it might be seen by an eye that has passed through death, or by a soul that has been lost in its meanderings.

So one wonders: what would we really see if we could “just listen,” as the title of the exhibition suggests? More importantly, if we could listen to ourselves in front of these images, what would we feel emerging from the background? Fear? Desire? Recognition?

Taburet confronts us with thedark that inhabits us. But he does so with grace, with irony, with that grave lightness that only great storytellers possess. And in the end, each of his paintings is a boundary: between the human and the animal, between the visible and the invisible, between the self and the other. But that boundary, his painting suggests, has always been illusory.

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.