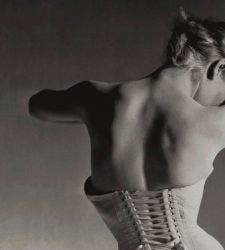

Photography

Photography

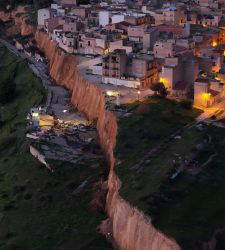

Museums

Museums

Museums

Museums

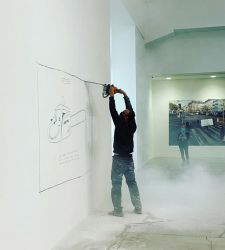

Contemporary art

Contemporary art

Ancient art

Ancient art

News

News

Exhibition reviews

Exhibition reviews

Exhibition reviews

Exhibition reviews

Exhibition reviews

Exhibition reviews

Exhibition reviews

Exhibition reviews

Exhibition reviews

Exhibition reviews

Opinions

Opinions

Opinions

Opinions

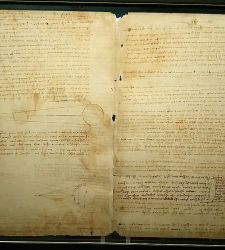

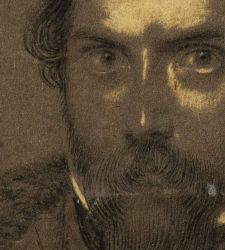

Works and artists

Works and artists

Works and artists

Works and artists

Works and artists

Works and artists