One of the lesser-known merits among the many that can be attributed to Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti is that he was among the first, if not the first, to make use of a historiographical method for a living artist. It happened in the immediate postwar period, when the Lucca historian and art critic set out to compile a monograph, published in 1948 by Edizioni U of Florence, on the work of his friend Carlo Levi. It was not only the sealing of a friendship that had been born in the 1930s, in Rome, where both had gone for reasons that, curiously enough, had to do with cinema and not with art: both, young men, worked in the field, Levi as a set designer and Ragghianti as a very young critic at his debut (and in any case among the first to deal with cinema), and both were looking for work. The book was also the first critical arrangement of Carlo Levi’s entire oeuvre: Ragghianti had published a sort of catalog raisonné that included everything. Paintings, prints, drawings, watercolors to draw up a complete profile of Carlo Levi with the typical methods of art history, twenty-two years before Filiberto Menna became the holder, in Salerno, of the first chair of contemporary art history in Italy. Tracing the origins and development of the friendship between the critic and the painter, as the exhibition Levi and Ragghianti aims to do. A Friendship Between Painting, Politics and Literature currently underway at the Fondazione Ragghianti in Lucca, thus means tracing one of the most significant episodes in postwar Italian art.

Therefore, it was with the monograph on Levi that Ragghianti was able to undertake an operation that Paolo Bolpagni, curator of the Lucca exhibition together with Daniela Fonti and Antonella Lavorgna, defines as “revolutionary”: “it was no longer a matter of chronicle, nor of practicing elegant literary lambasting, but of considering that even coeval creative expressions could and should merit a ’philological’ analysis, an indispensable prerequisite for the exercise of criticism.” However, the friendship between Ragghianti and Levi, cemented by their common political vicissitude (both anti-fascists, both active first in the Partito d’Azione and then in the Tuscan Committee for National Liberation, of which the critic was president), was not the reason for the decision to proceed with an initial historicization of the Turinese painter’s work. Ragghianti considered Levi, for well-founded reasons, to be one of the most interesting contemporary Italian artists. He had explained this well in the brochure of Levi’s solo exhibition held in 1946 at the Galleria dello Zodiaco in Rome: “the fact that struck me most in his painting, especially in comparison with the pictorial experiences that it was then given to verify among the most intelligent and gifted,” we read, “was the way in which he showed that he mastered a complex of experiences that were identified with the coppery formation of the modern pictorial language. It was possible to detect in the paintings some essential references to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, traces of further experiences: the brushstroke, the cut of the compositions, the chromatic synthesis, the sensitivity in the choice of the signifying appearances of the object, some unexhausted fragments of problems and curiosities.” Added to all this was an “extraordinary, torrential vitality,” authority before the masters, spontaneity, freedom, originality of vision, complexity of the fabric of his painting, and great versatility.

An itinerary built with works mostly coming from the Carlo Levi Foundation in Rome and marked in six stages along the rooms of the Ragghianti Foundation in Lucca chronologically reconstructs the stages of the friendship between Ragghianti and Levi, which can nevertheless be gathered around three main strands (the beginnings and the common ground that led to mutual acquaintance, the experience of the war and the years of exhibitions and critical reconnaissance), with some, notable thematic incursions, for example the Carlo Levi of cinema.

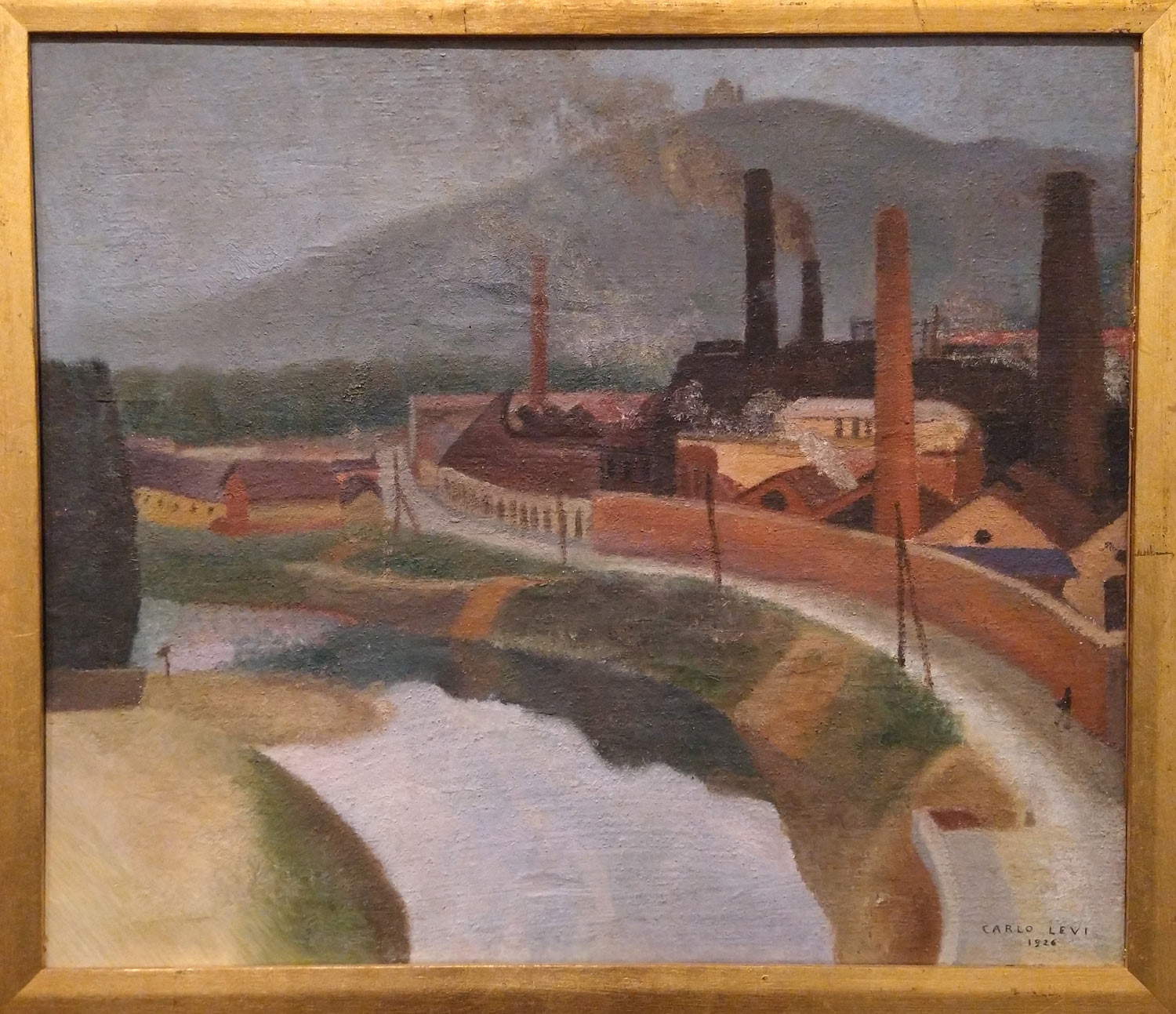

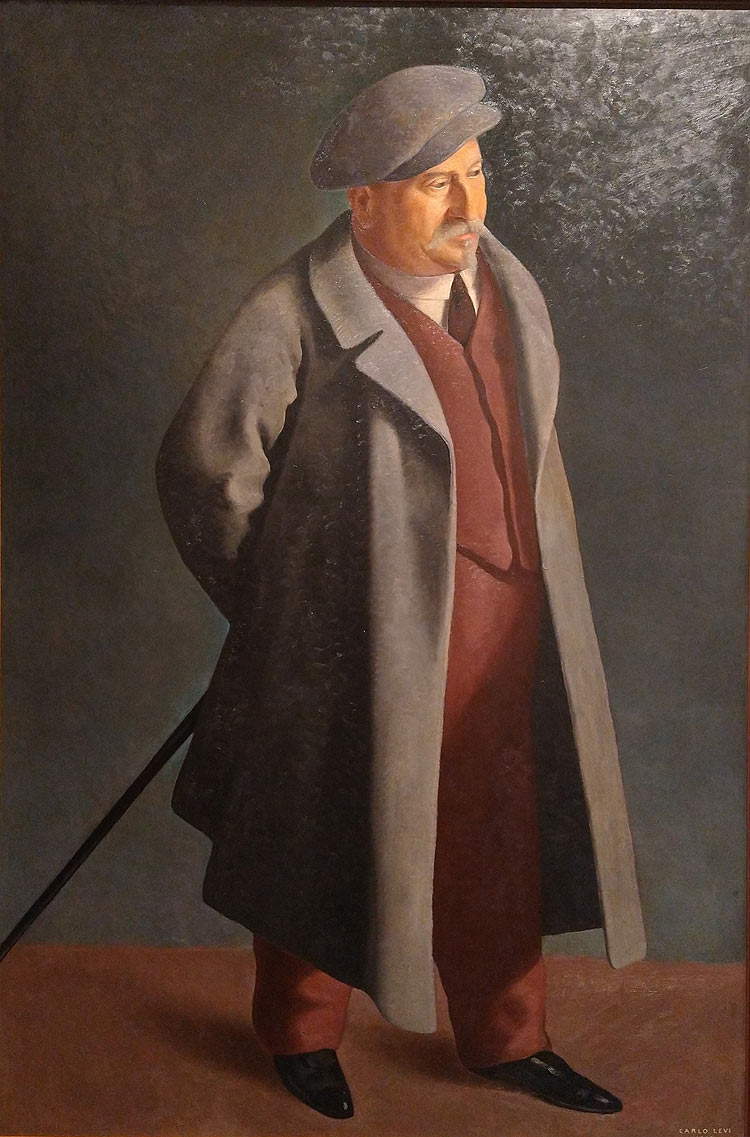

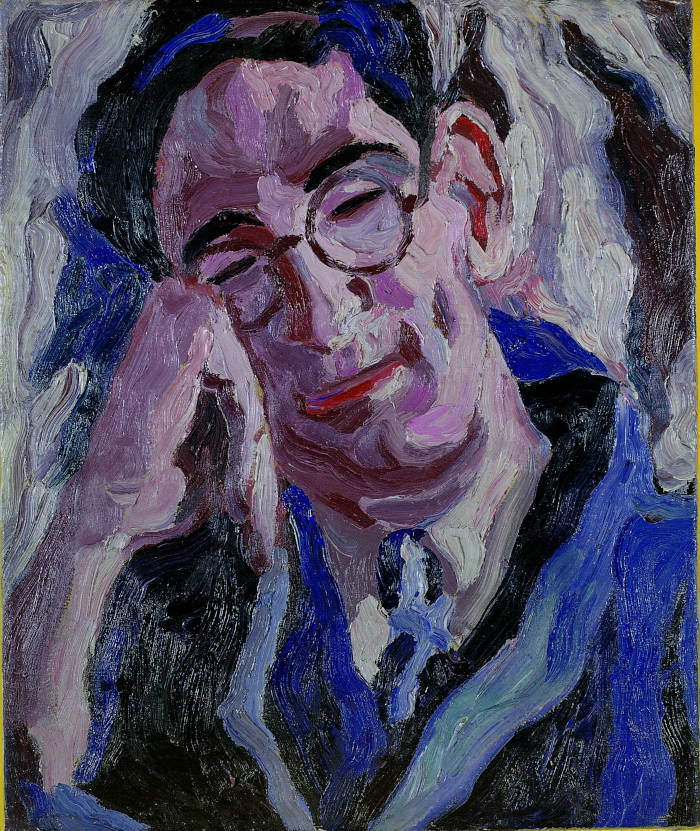

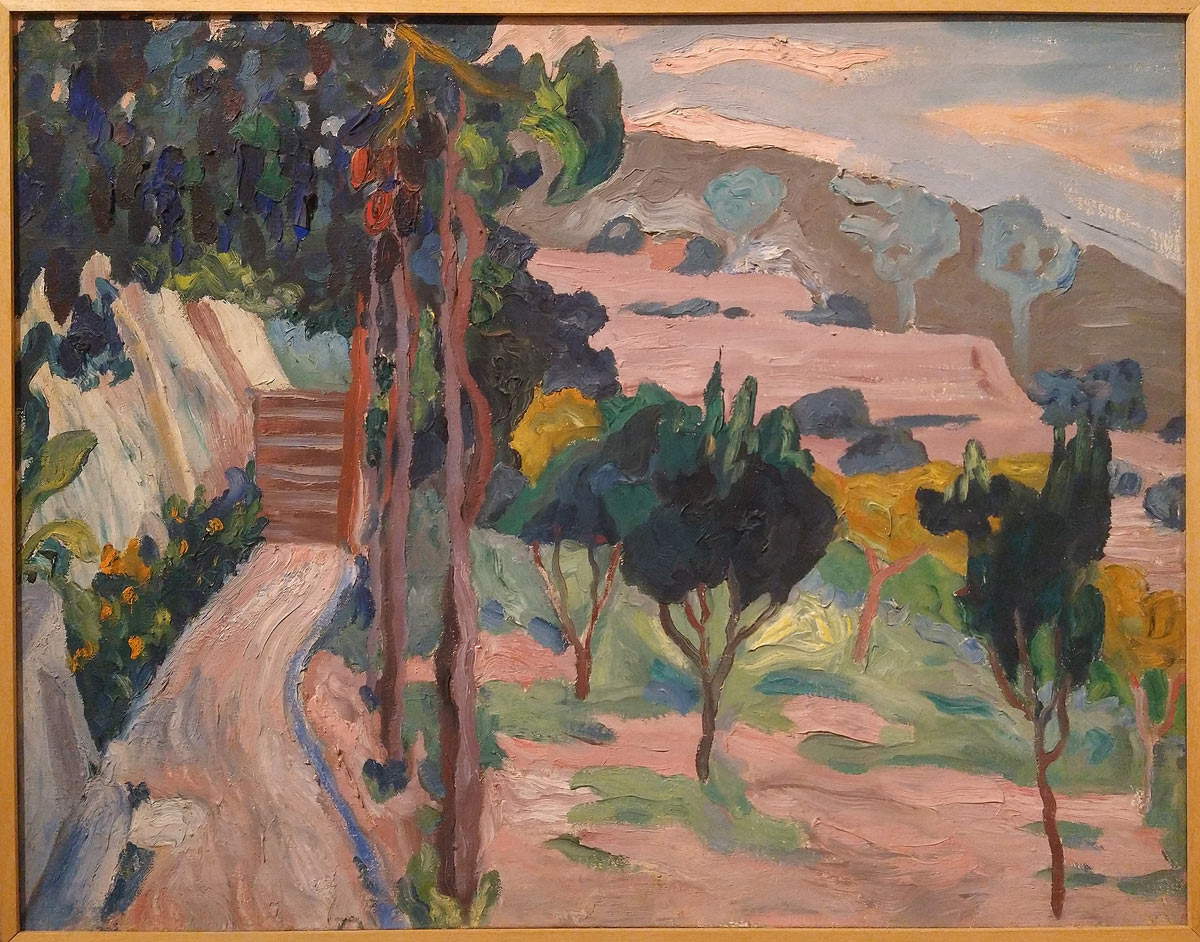

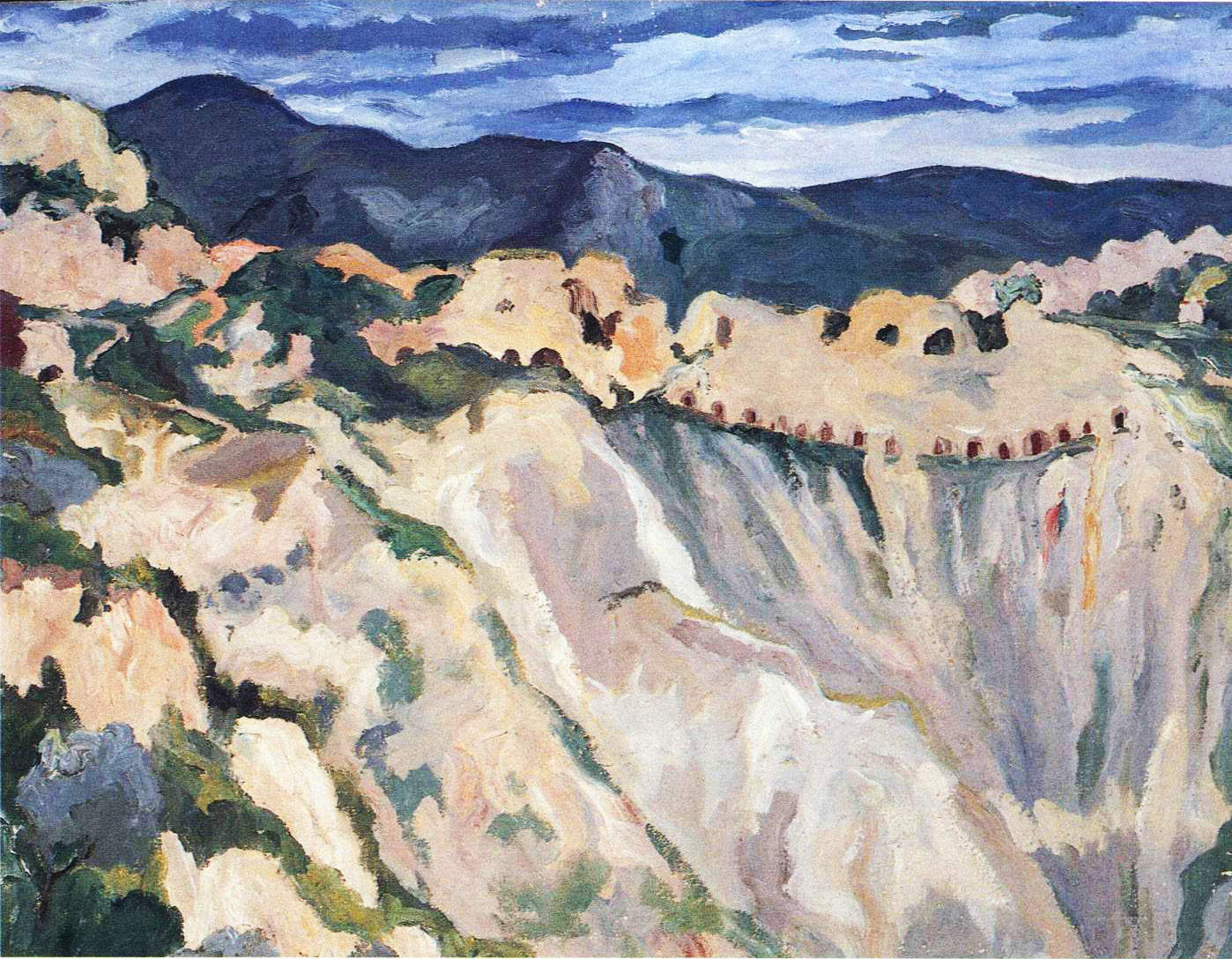

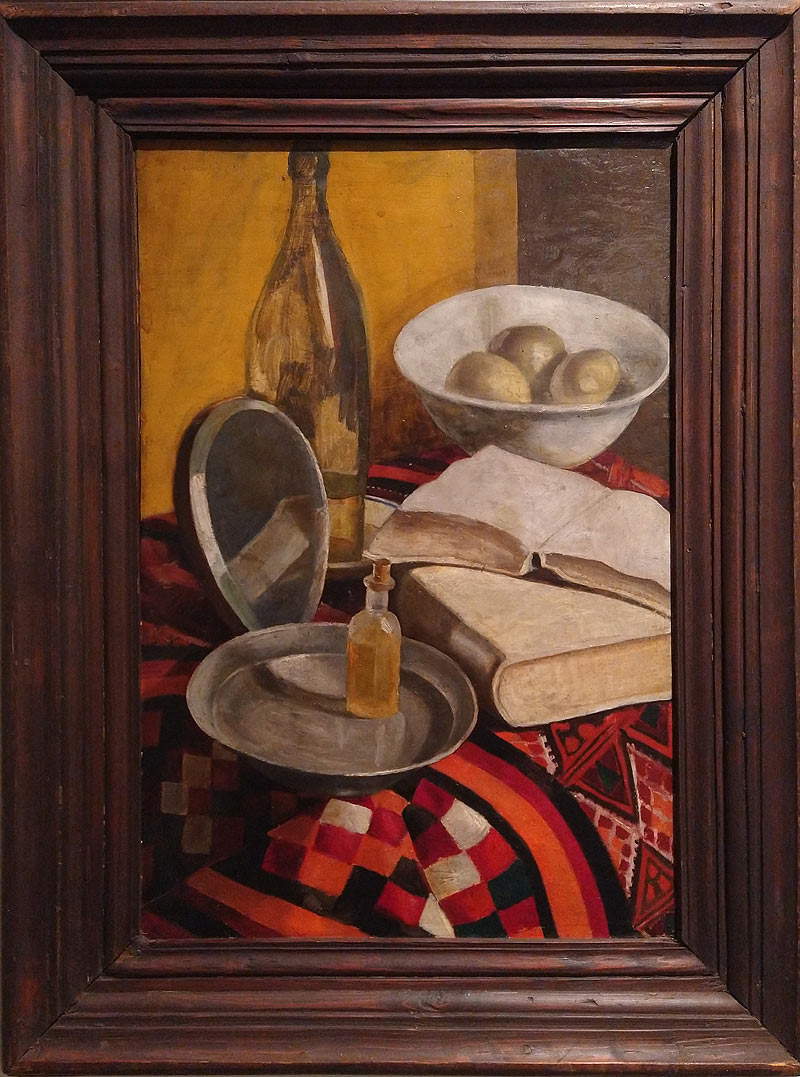

The first, introductory section is devoted to Carlo Levi’s formative years, but the curatorial choices extend to include paintings from his early maturity, works in which we see a rather obvious change in the artist’s language. We do not start with the oldest works among those in the exhibition (the earliest are in the last section), but the visitor is nonetheless given the opportunity to admire the young Levi who, in his early twenties, in the general climate of rappel à l’ordre after the First World War, proposes a figurative painting that looks to the French avant-garde of the late nineteenth century, but is nonetheless strongly rooted in contemporaneity. It is a sober painting, that of Carlo Levi: in the landscape paintings, such as The Gasworks and The Sails, two works executed close to each other (in 1926 and 1929, respectively), the language of the French painters is updated with compositions based on rigid, almost geometric scores (this is seen above all in The Gasworks, but it is also clear from the squared solid that gives shape to the cabin on the sea in The Sails), which, however, do not give up an intimate, almost contemplative dimension, and which still manages not to be nostalgic. It is Carlo Levi’s personal response to that need for representation of reality that is typical of the mid-1920s. Nor does the artist renounce tradition: the Negro at the Tuileries, one of the peaks of the Lucca exhibition, is founded on a crystalline neo-Renaissance perspective. And then there is the portraiture, which in this beginning of his career, writes Daniela Fonti, goes on the one hand in the direction of an “almost neo-Flemish analytical rendering of reality, which has not a few assonances with the German New Objectivity” (a trait that is, however, also common to other genres practiced by the artist) and on the other hand in that of an ability to adhere to reality “in a more intimate and direct way”: The father walking and The mother and sister are the most significant examples. With the 1930s and his assiduous frequentation of Paris, Levi’s grammar became decidedly freer and looser, as well as rooted, Fonti writes again, “powerfully in the authenticity of existential experience.” It is from the everyday that the artist has always derived the subjects of his works, and this everyday, in the years of his early maturity, emerges from the canvas in an even more heartfelt way, with fluid and often nervous brushstrokes. The Gran Madre is a view of cold, modern Turin, the Landscape of Alassio is instead the transfiguration of a cherished place, and the Portrait of Leone Ginzburg is an example of how this new expressionism of Levi’s also invests the portrait genre.

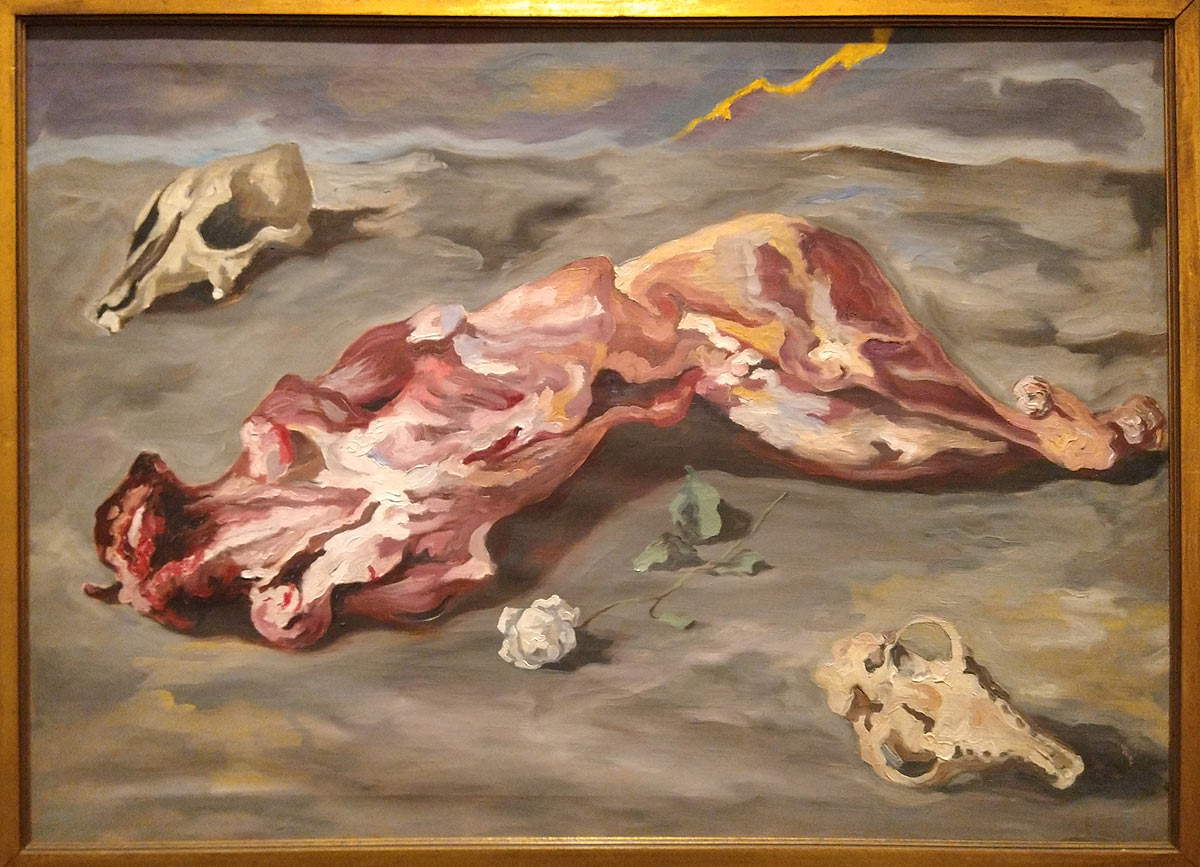

The juxtaposition to the art of the Fauves becomes more stringent in the years of the World War, on which the second section intervenes, which also begins to develop the theme of the friendship between Ragghianti and Levi by entering into the merits of the political struggle, the clandestine situation, and the common stay of the two in Florence. Levi, in the years before and immediately after the conflict, feels the vivid need to oppose the regime also through art: “if on the one hand,” writes Francesco Tetro, “the artist makes his own the positions of Piero Gobetti and Edoardo Persico on the theme of unity and ideal continuity between the arts and intellectual freedom against the nationalism of the regime, the founding idea of painting as a place of critical autonomy, ethical commitment and overcoming the causes of the marginality of Italian art makes its way.” Levi is affected by the racial laws, is forced to go to France for some time (and cannot return even when he is caught by the news of his father’s death in 1939), and returns to Italy only when the war has already begun: in these years he devoted himself predominantly to portraits (the exhibition includes a beautiful portrait of his wife Paola, unpublished, from 1937), and his painting, even in this genre, became almost impulsive, irrepressible, even more material and dense (the Three Nudes of 1938 are disturbing), while the few works that deviate from the main vein followed by Levi in these years convey the idea of the tragic nature of the historical contingency. Not only where episodes of war are directly narrated, as in Fucilazione or the even more atrocious Guerra partigiana, but also in the many still lifes (such as those depicting Funghi) where the elements call to mind battlefields. An in-depth thematic study is devoted to the years of confinement in Lucania, from which the book Christ Stopped at Eboli, Carlo Levi’s best-known work, would spring: these are paintings made during those years (mainly portraits, but also views of the silent, rugged Lucanian valleys) but also works created long after the book’s publication.

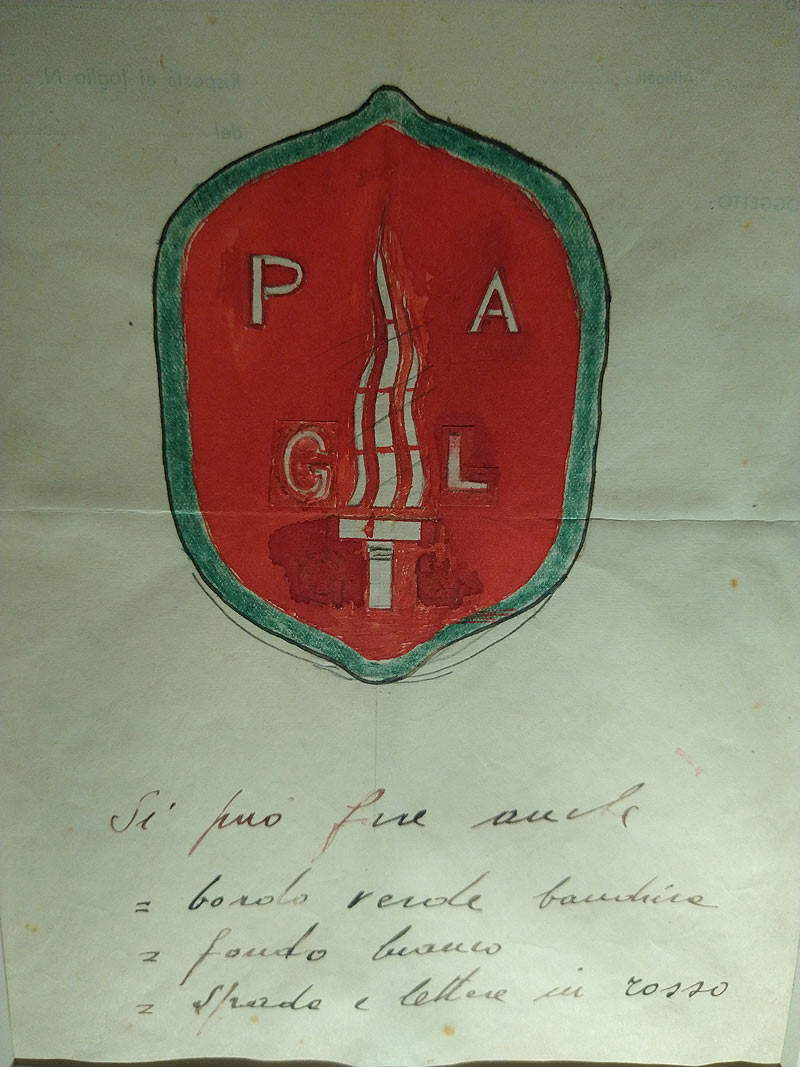

The closeness between Levi and Ragghianti during the war years is then particularly deepened in the section devoted to “wartime drawings,” with sheets arriving from private collections and from the Gabinetto Viesseux: from Florence, in particular, comes the sketch for the emblem of the Partito d’Azione, the movement founded in 1942 in Rome and disbanded five years later, into which Justice and Freedom would later merge. Ragghianti himself participated in the founding of the Partito d’Azione, who also collaborated in drafting the points of the program: in the catalog, an in-depth essay by Roberto Balzani reconstructs in great detail the political ideas of Levi and Ragghianti and their experiences at the time of World War II. Common to both of them was then their passion for cinema, to which another room is dedicated: at the beginning of the 1930s, Levi had in fact begun working as a set designer, and among his best experiences related to cinema can be counted his participation in the 1938 film Pietro Micca. The full-length film is now lost (only a five-minute reel remains: they are shown in the exhibition), but there remain thirty sheets of Levi’s drawings, sketches and watercolors, all of which are preserved Museo Magi ’900 in Pieve di Cento, that testify to Levi’s role as set and costume designer for the film. Some of them are on display in the exhibition, along with other works related to cinema, including portraits of actresses and some drawings from the 1960s traced on paper on newspaper, in continuity with the verbo-visual research of the time: these sheets represent Levi’s closest approach to these modes of expression.

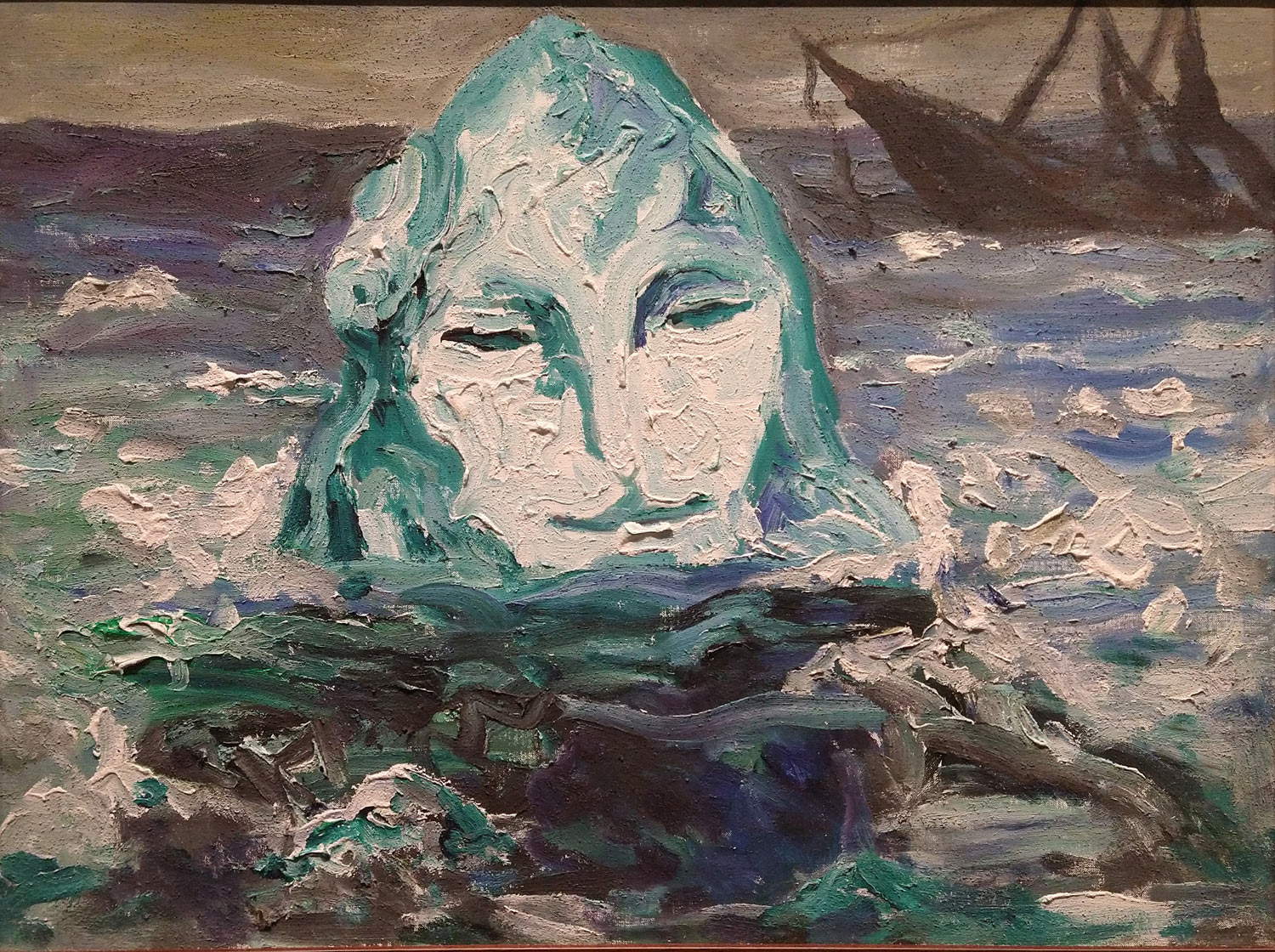

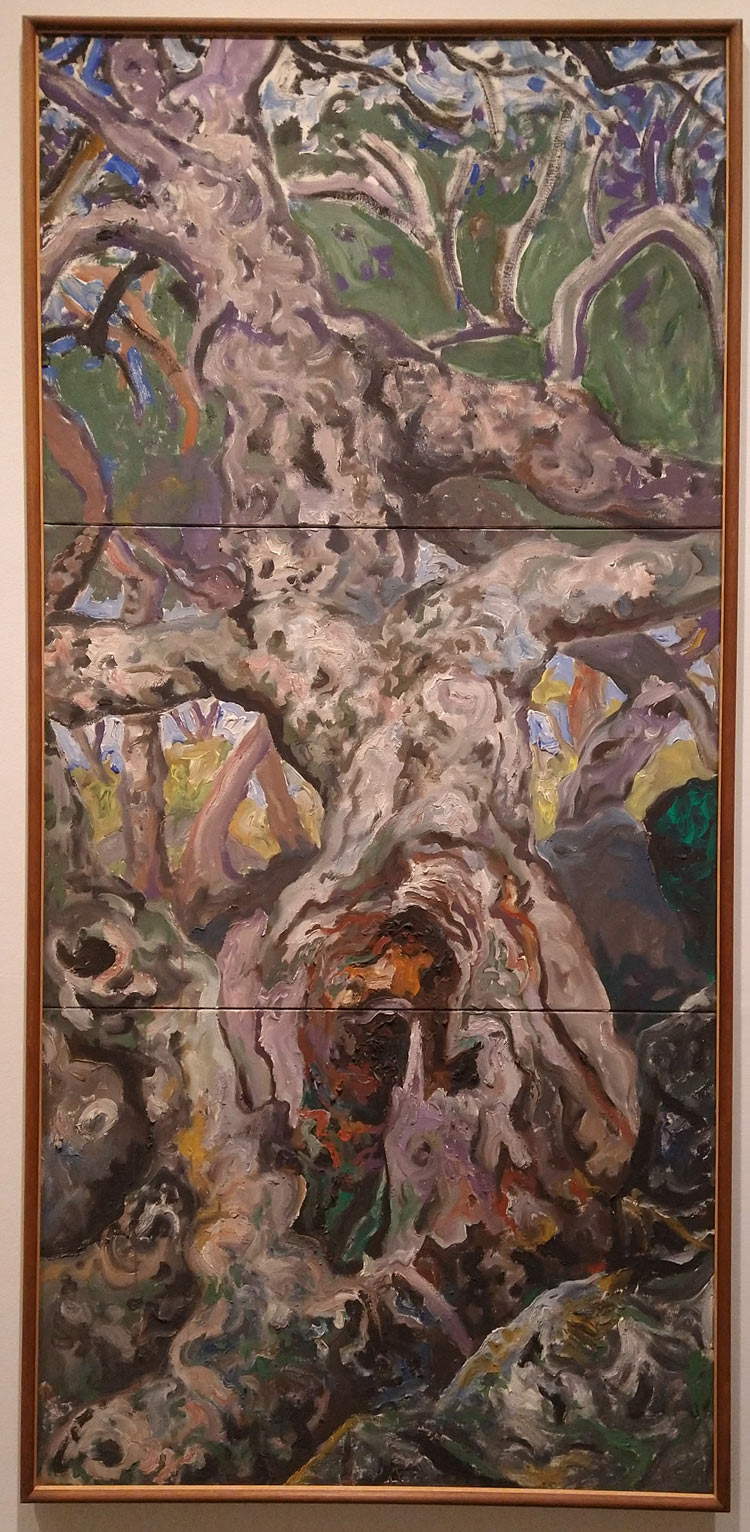

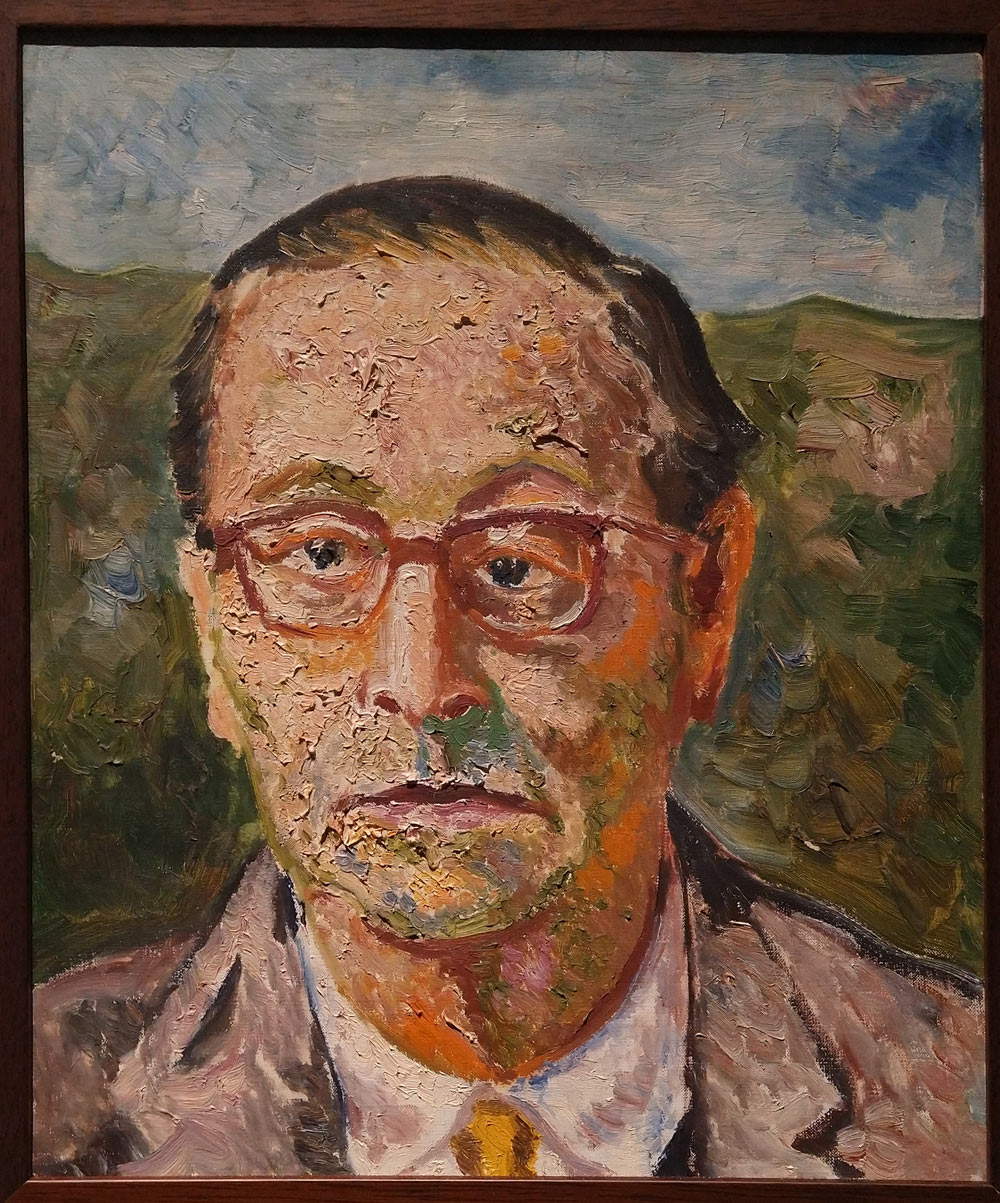

A demanding archival work, of which Antonella Lavorgna gives an account in the catalog, is the basis of the last section, dedicated to Carlo Levi seen through the eyes of Carlo Ragghianti. The curators’ choice sought to reconstruct the critical path that Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti imagined in the postwar period to situate the work of Carlo Levi: thus ranging from the youthful works (there is also a Still Life from the 1920s, the oldest work among those in the exhibition), through the works of the 1930s, including the famous Self-Portrait in Black and White, to the masterpieces of his maturity, with a room that gives an account of all phases of Carlo Levi’s painting, including the experiences of the 1950s and 1960s, a period during which Carlo Levi’s expressionistic language settled down to forms not unlike those that had characterized his works of the 1930s, although that sense of impending tragedy that permeated the works of the war years is diminished and instead a dreamlike vein emerges here and there (see, for example, The Iceberg and the Shipwreck). Then the themes dear to the artist, such as nudes and familiar landscapes, return: also on display are two monumental paintings depicting carob trees, the trees Levi used to see in Alassio where he spent frequent stays for pleasure. Finally, to close the discussion, here is the 1969 portrait of Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti. It would have been the Lucchese critic himself, writes Francesco Tetro in the catalog, “who emphasized how Carlo Levi’s portraits, if meditated on from a sociological point of view, represent the best constituent elements of his biography; because the artist, scrutinizing the humanity he encounters, appropriates it, recognizes himself in it in order to tell about himself, in an interest that always leads back to the portrait.”

The last room also includes a documentary appendix: letters, documents and texts also restore the relationship that bound the two with words, and particularly with the exchanges between painter and critic, even those of a more ordinary nature. A useful appendix to bring out, even with the force of the vicissitudes of everyday life as well as that of painting, the humanity and strength of the bond between Carlo Levi and Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti. A research exhibition, then, which intervenes on a theme that is unprecedented for an exhibition review, expanding the view to the context of the historical and cultural events of Italy between the first and second postwar periods. And exhibition that sums up about a hundred works: the quantity of the works gathered allows therefore to read the itinerary also according to different reading plans. Narrative of a bond between two great intellectuals of the 20th century and reconstruction of the entire story of one of the major Italian artists active in the middle of the century. Insight into the methodology of contemporary art history and focus on the relationships between art and cinema, art and graphics, and art and life.

Review, finally, exquisitely and inevitably political, as is natural for an artist who considered commitment inherent in his art and for a critic whose activity can hardly be separated from political passion. Not least because the struggles of both followed well after the war: the two found themselves even in the 1960s “side by side in a battle that had as its purpose [...] the affirmation of the value and autonomy of culture in itself, against the primacy of a development with no apparent design outside of consumption and the construction of an ’affluent society,’ as it was called at the time,” Balzani writes in the catalog. Levi’s commitment would also be recalled by Ragghianti in 1977, on the occasion of the first posthumous exhibition of the artist’s work, held in Turin: in the introductory text, Ragghianti emphasized from the first lines how Levi was “a man of extraordinary humanistic culture and committed ethical-political culture, who polarized his personality in painting.” A personality that the exhibition well reconstructs, in the sign of a fruitful fellowship.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.