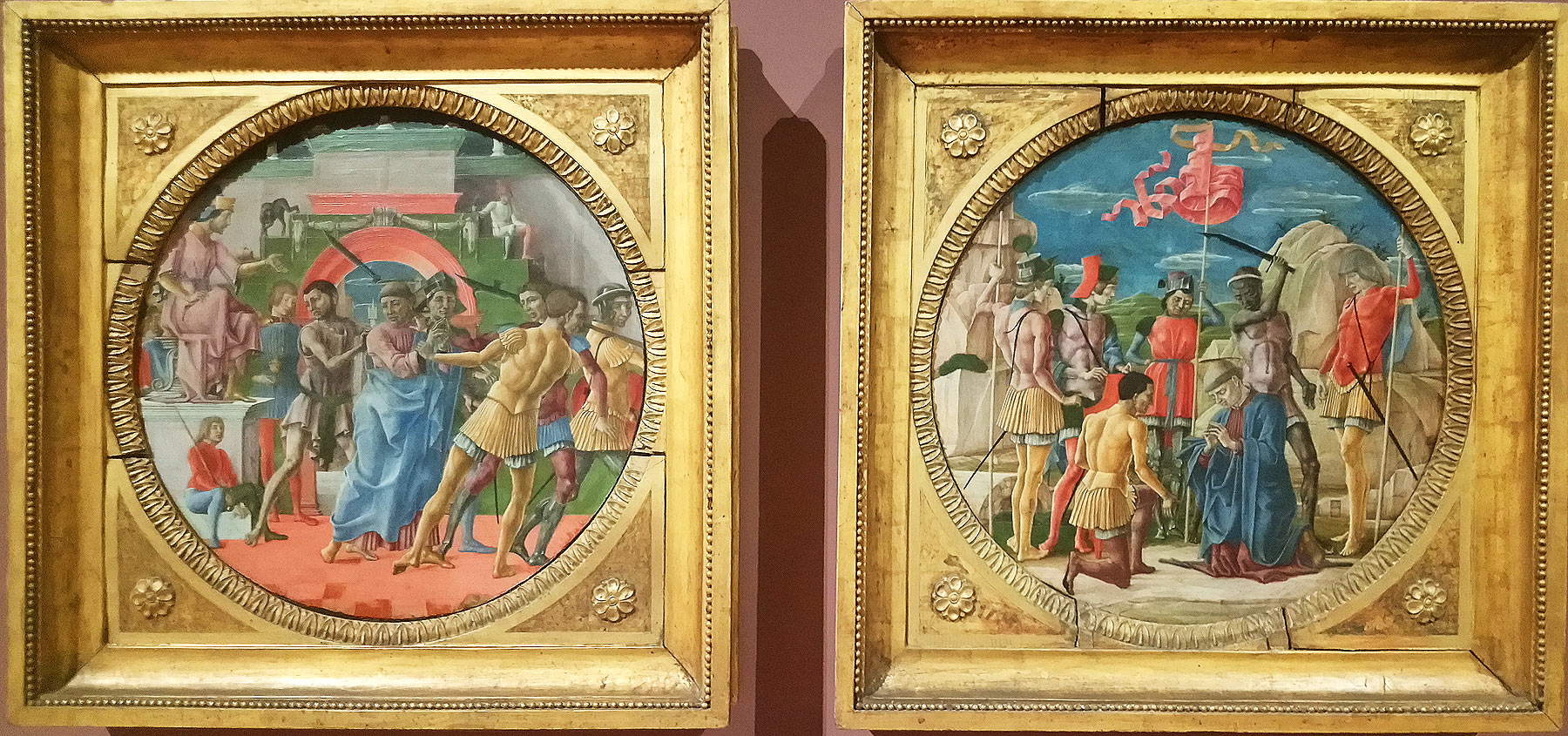

If we were to identify, in Cosmè Tura’s entire production, a single detail that could serve as a summary of his expressionist painting ante litteram, nervous, sculptural, so crazy and disturbing, so far from the orderly and seraphic Renaissance that took root with deep and invasive roots in the collective imagination, we would not need to bother searching for long: it would suffice to look at the banner held up by one of the thugs that the painter inserts in the Martyrdom of Saint Maurelius, a tondo preserved at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Ferrara: a rosy weathervane twists around the long pole, forming impossible metallic folds, fluttering with flaps that look like long tentacles, going to occupy the sky (one of those many skies swept by the tramontana, almost enameled, that do not just act as a background, but are among the highest protagonists of Cosmè Tura’s art) with a presence that we perceive almost as being out of place, foreign, alien. Cosimo di Domenico di Bonaventura, who entered art history with his dialectal nickname and diminutive patronymic, is the first and most visionary of the painters of theeccentric Ferrara workshop, he is the artist who knows how to imprint his compositions with that “diabolic and questioning rhythm” that Longhi attributed to him, he is a man who lives in a “wholly mental world,” wrote Piero Bianconi, and who is “locked in a fascinated and exasperated mannerism,” he is a lover of the complicated and the unusual, a sort ofarchaeologist of the fantastic who brings to Ferrara the culture of antiquarian Padua to translate it into a dreamy, improbable and restless antiquity, a painter who is little framed, modern and sighing, attentive and nostalgic.

The Martyrdom of St. Maurelius, and the work that precedes it in the narrative, the Judgment of St. Maurelius, are among the very rare examples of Cosmè Tura’s art that have survived in his Ferrara. They have been part of the Pinacoteca’s collection for more than two centuries, that is, since 1817, when a local collector, Filippo Zafferini, gave them to the City of Ferrara in exchange for an altarpiece by Bastianino. The two tondi were formerly part of a dispersed polyptych, of which they are the only surviving elements, and which adorned the altar dedicated to the saint in the church of San Giorgio fuori le mura, the city’s oldest house of worship, where the saint’s remains were transported in the 12th century. Maurelius, along with Saint George, is the patron saint of Ferrara, and when Cosmè Tura painted the polyptych from which the two tondi come, in the early 1480s, his cult was recent, since the bishop who came from Edessa was proclaimed patron of the city only a few years earlier, in 1463.

According to the myth, Maurelius, who lived in the seventh century, was the legendary son of King Theobald of Mesopotamia, who for the sake of faith renounced the throne when his father died, preferring to embark on a spiritual path in the sign of God: settling in Smyrna, he was involved in a dispute around a local heresy and to resolve it decided to undertake a journey to Rome to expose the problem to Pope John IV. As chance would have it, he arrived in Rome just at the time when some pilgrims from Voghenza, who had come to the papal see to report to the pope that their bishop had recently passed away, and thus to ask for a successor, were also in the eternal city. Apparently, St. George had appeared to the pope in a dream to instruct him to appoint Maurelius as bishop of Voghenza: the young man accepted and immediately moved to the Ferrara area, where tradition attributes to him a series of healings and miracles that would later ensure his timely canonization. Legend has it that Maurelius had then returned to Edessa to settle a dispute between his two brothers: having arrived in his homeland, however, he would continue to preach the message of Christ there, and for that reason he would be judged, sentenced to death and executed.

|

| Cosmè Tura, Judgement of Saint Maurelius (c. 1480; oil on panel, diameter 48 cm; Ferrara, Estensi Galleries, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Cosmè Tura, Martyrdom of Saint Maurelius (c. 1480; oil on panel, diameter 48 cm; Ferrara, Estense Galleries, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| The two tondi. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

What Cosmè Tura depicts in the Ferrara tondi are the last moments of Saint Maurelius’ life. In the first, the Judgment, Maurelius receives the judge’s response, seated on a plinth that serves as his curious stool, and is already being escorted by some thugs to the place of martyrdom. We find the same soldiers again in the martyrdom tondo, where St. Maurelius, kneeling and gathered in prayer, firm in his faith, is about to receive the mortal blow. And he receives it from an African, since in the fifteenth century one did not go for subtlety and dark skin was often associated with the infidels, although here the Moor is above all, Mario Salmi has noted, a “note of color.” It is surprising, however, that the thugs are not charged in a negative sense, but seem to show a motion of compassion toward the saint’s sad fate. And it is an even more interesting note, perhaps the most fascinating in the Martyrdom and among the peaks of Cosmè’s painting: the faces of the bystanders are marked by a veil of melancholy, the soldiers watch the sad execution in absolute silence and without flinching, with almost affected gestures, and one of them even kneels in front of Maurelius, as if to comfort him. Marcello Toffanello spoke of an “atmosphere that seems almost of mutual understanding between the executioners and the condemned man.”

This atmosphere, too, is part of the “mental world” that the leader of the Ferrara workshop deploys in his two roundels. It is a world all his own, a world that can hardly be found with as much density and as much imaginative flair in the production of other contemporary artists. In the first tondo, the environment presents contemporary architecture, “of a clear and happy chromatic variety, from pink to green to red to purple,” we read again in Mario Salmi, “architecture united with the perspective slope of theterracotta planting, of two tones, and adorned with some classical motifs such as bucranî and festoons,” architectures where there is no lack of elements inferred from the real world in which Tura lived, namely the little monkey climbing on thearch, an animal that the painter must have seen at some reception at the Estense court, or the page who sits at the base of the improvised throne of the judge, or the one who, for some reason, wanders behind the thugs holding in his hand a very precious and very rare vase of’gold in an unusual and sought-after fashion, or the other, even more absurd, who sits on the arch, almost bored, in symmetry with the little primate, and holds a falcon on his glove, another obvious expression of courtier solace. The Martyrdom is set against the background of an equally far-fetched landscape, only it is set outdoors, among stony cliffs and round, regular clouds that look like disks made of air, with the space that is punctuated by the very thin poles of the banners that the torturers hold up at a regular distance from each other.

The dating to the 1980s is due to the fact that, compared to earlier works, here Cosmè Tura squares a narrative that is more relaxed, more balanced and calmer than those, extremely excited, that had marked the earlier phases of his career, compared to the “diabolical rhythm” that he had been able to confer on certain of his unrepeatable compositions: the antecedents of the Ferrara Cathedral organ constitute one of the most dazzling examples. But there is no lack, meanwhile, of his Paduan cultural references, here again indebted to the Mantegna of the Ovetari Chapel. Nor is there any shortage of the recurring glacial preciousness of his subject matter, the glassy colors, the sharp, hollowed-out profiles, the close-fitting robes and armor that anticipate the painting of the late sixteenth century, the iron draperies that unite the figurative texts of Cosmè Tura and that are participatory elements of that dual nature that furrows his painting and which has been so well described by Bianconi: “a nature that, while remaining fundamentally Gothic, fabulous, approaches the Renaissance vision, the example of Piero della Francesca and Donatello, resulting in singular outcomes, in a fantastic rovello, in gnarled and twisted forms, in a restlessness that, though in its own way, participates in the spatial peace of those great Tuscans.”

If you enjoyed this article, read previous ones in the same series: Gabriele Bella’sConcerto; Plinio Nomellini’sRed Nymph;Guercino’s lApparizionedi Cristo alla madre; Titian’s Magdalene; Vittorio Zecchin’sOne Thousand and One Nights; Lorenzo Lotto’sTransfiguration; Jacopo Vignali’s Tobias and the Angel; Luigi Russolo’s Perfume; and Antonio Fontanesi’sNovembre.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.