April 2025. Coachella. A legend appears on stage and time does not stand still. During one of the festival’s most anticipated evenings, Benson Boone (a young artist who grew up in a system that favors accessibility over emphasis and continuous storytelling over distance), singing Bohemian Rhapsody, introduces former Queen guitarist Brian May to the stage. Not a hologram, not a nostalgic quote: it’s really him, with the Red Special around his neck, the familiar posture, the exact body of a legend who has spanned eras, revolutions, mourning and rebirth. The intent is to pay homage and bring history into contact with a present that seems to have lost its lexicon. But something is jammed, the apparition takes place and the ritual is not fulfilled. The audience, mostly very young, remains still. There is no roar, no emotional tension, no suspension that once accompanied the entrance of a mythical figure. There is only a myriad of raised phones, an automatic, almost reflexive response, documenting what he cannot interpret. May’s guitar draws the final phrases of Bohemian Rhapsody with his usual dissonant elegance, while Boone’s voice dutifully accompanies him. But every gesture, every note remains suspended, as if the emotional frequencies of both generations could no longer align, no longer understand each other.

Yet this is not nostalgia, nor is it generational superiority. The distance is not between fathers and sons, but between symbolic codes that no longer coincide, and in a time that changes with a speed that is difficult to archive, it is possible for the founding gestures of one generation to be invisible to the other, not so much through rejection as through a normal mutation of languages. It is a grammar of recognition and, like any grammar, it works only if someone knows its syntax. But when the myth finds no witnesses, when the myth begins to disappear, then it can no longer act as such and remains a form without function, a surface that refers to nothing. And it is precisely this suspension of meaning, this mute survival of signs, that visual art has been able to explore intensely through a poetics of disappearance, often anticipating the experience of the unheard gesture, of the form that addresses a now-absent recipient. It is the persistence of the undeciphered visible, of all that remains when memory still exists but can no longer be activated.

The work of Rachel Whiteread, a British artist who has always worked on the idea of the negative, has been moving in this context for decades. Her practice involves making casts (usually in concrete, resin or plaster) of the spaces that objects contain, such as the inside surface of a closet, the air under a chair, the inside of a room. In this way it is solid matter that gives form to the void, making it a visible, tangible, full object

His most famous work is House from 1993. For this project, the artist intervenes on a disused building in northeast London, a dwelling destined for demolition, and makes its interior cast in concrete. He works directly inside the empty spaces, casting mortar directly into the rooms, stairs, and hallways and reinforcing the structure with metal reinforcement. To finish, he patiently removes, brick by brick, the outer shell of the house, and what emerges is the full mass of absence: the compact negative of inhabited spaces, the inert outline of all that has been lived in, now rendered impractical, intact and alien.

Although it was intended from the outset as a temporary installation, House elicited mixed reactions: many visitors flocked to the neighborhood to see it, turning it into an ephemeral monument to urban loss, but among residents and members of the local government distrust prevailed. For some, in fact, it was just a burden and a senseless paradox in an already fragile neighborhood, and the sculpture remained in situ for just eighty days, being demolished before its scheduled deadline. Yet in that very brief interval, House imposed itself as the most intense testimony to private memory made matter, a monument to the invisible presence of everyday spaces, their endurance and their inevitable dissolution in the loss of meaning.

But perhaps his cruelest and most necessary work remains theHolocaust Memorial, made in Vienna in 2000. Here, Whiteread builds an enclosed library: a concrete monolith, as massive as a bunker, where inward-facing book spines are inaccessible, invisible, imprisoned. The edges of unread pages line each side of the massive structure, suggesting clamped volumes, compressed into a space with no exit and, above all, no access. It becomes, thus, a closed, opaque body, repelling the gaze and at the same time holding it back. According to the artist, those unturned pages represent the unlived lives, the broken stories of Holocaust victims. On the lower edges of the block, carved in stone, appear the names of the death camps where too many among them found their deaths. The monument stands on Judenplatz, next to the remains of a destroyed medieval synagogue and a museum dedicated to the history of Viennese Jewry, and it stands, today, as an irrevocable sign.

Again, its creation, promoted by writer and architect Simon Wiesenthal, was not peaceful. Indeed, there were countless delays, political tensions, bitter debates over the presence of such an absolute sign right there in the heart of the city, and, to top it off, the discovery of archaeological remains during excavations. But eventually the monument was completed and unveiled in October 2000 as a true act of denunciation; it was a warning Vienna owed to itself. At Whiteread’s request, the memorial was not protected by anti-graffiti coatings, and in this regard the artist stated, “If someone sprays a swastika on it, we can try to erase it, but a few painted swastikas would really make people think about what is happening in their society.” Simon Wiesenthal was equally clear: “This monument should not be beautiful. It’s supposed to hurt.”

And indeed it does hurt. House was about private loss; the Vienna Memorial, on the other hand, embodies collective erasure by forcing the community not to forget and opens as a space without consolation, a space of visible emptiness, where memory is shown in its highest degree of impossibility.

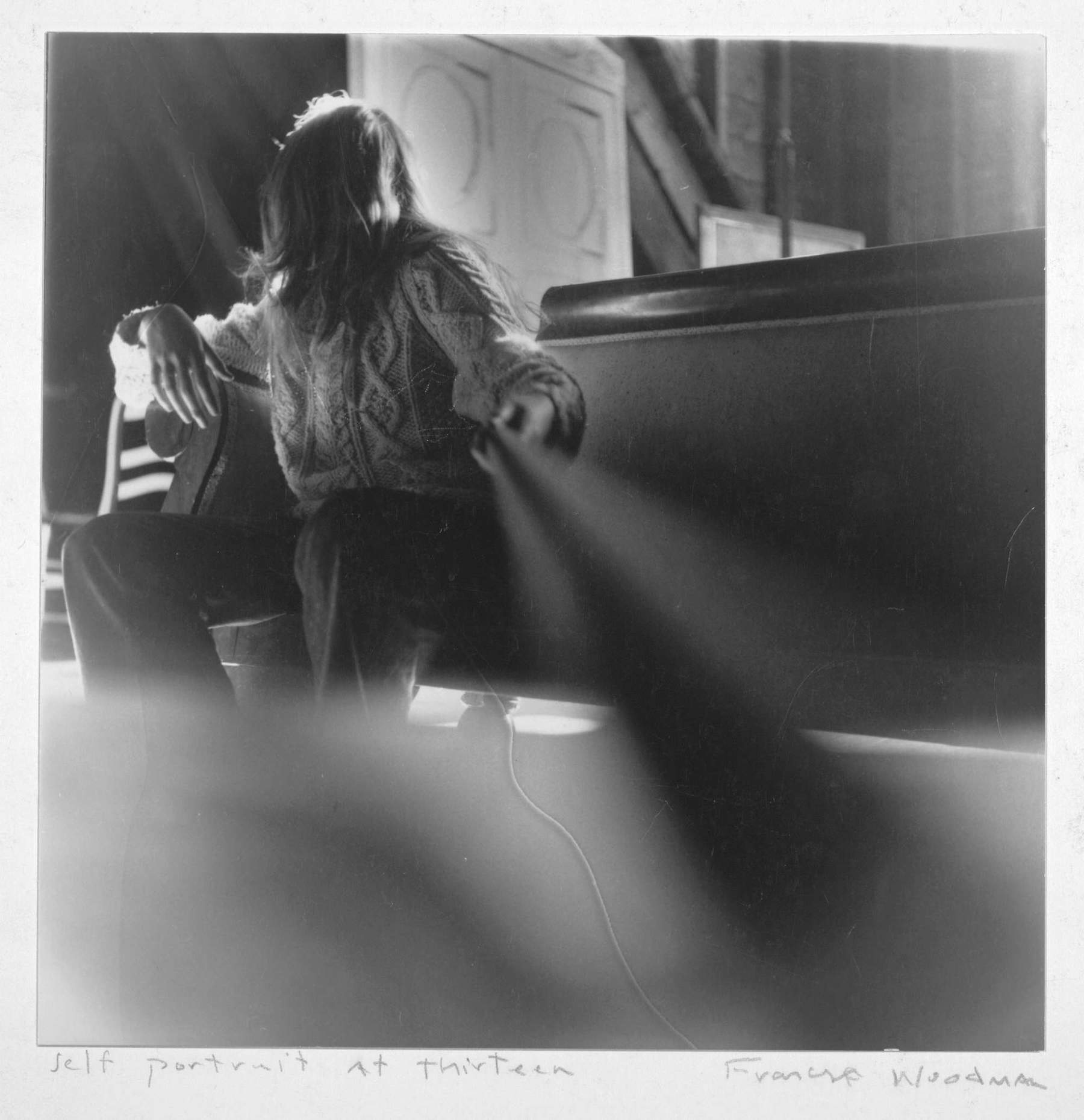

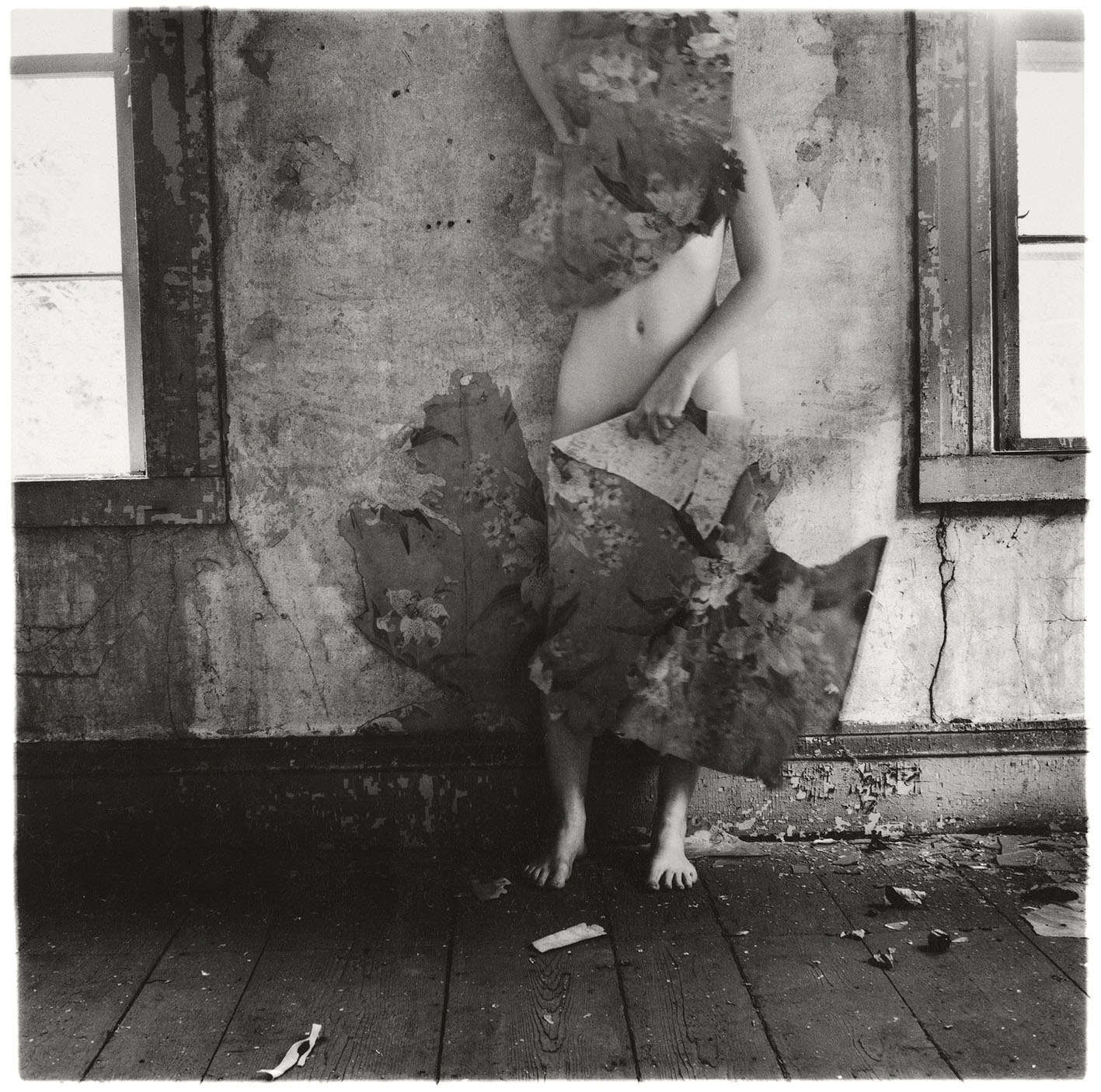

To a similar poetics, if diametrically opposed in form, belongs the work of Francesca Woodman, an American photographer who died very young (at the age of twenty-three, not yet completed, in 1981) and who made self-representation a vanishing strategy. Her photographs, all made between the ages of thirteen and twenty-two, render bodies that erase themselves, figures that overlap walls, dissolve between light curtains, blend into the shadows of abandoned rooms or break against opaque surfaces.

Woodman does not represent the body, but subtracts it, hides it, consigns it to continuous visual erosion. It is a poetics of imperfect appearance and announced disappearance, where the subject is there but remains ceaselessly elusive, unreachable, as if even photography, which is the quintessential tool of fixation, refuses to really stop it.

His self-portraits possess no celebratory will and do not speak of identity, but precisely of his inability to remain. They are gestures at once desperate and lucid, bodies that seek a space to exist even in the moment of disappearance.And so his images seem to ask the same question we ask ourselves today before the myths, icons, and fragile memories of our time: how long is a body still visible? And how much attention does it take to see what is fading?

In Whiteread and Woodman, what their works have in common is the suspension, the constant tension toward a gaze that never arrives, the form that offers itself but with no guarantee of being read, and the sign that remains, stubborn and unyielding, even when it has been deprived of its original function.

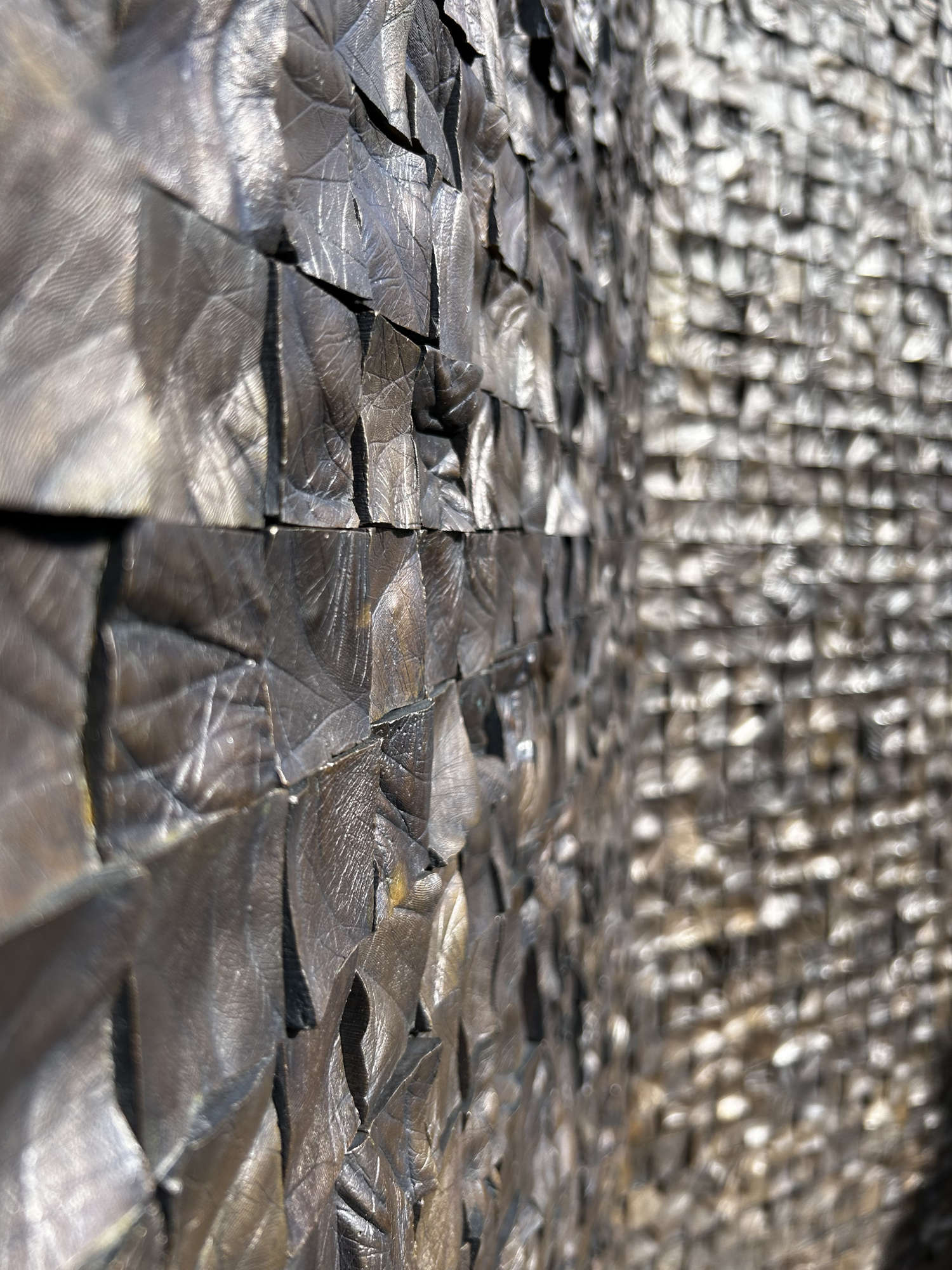

But there is another recent work that seems to return, gently and determinedly, a different possibility. This time not the celebration of myth nor the sublimation of absence, but a tangible, corporeal and imperfect form of memory made of minimal, repeated, shared gestures. It is At Rest, created by Selva Aparicio in Nieuwpoort, in northern Flanders. Made in 2023, it was born from a widespread and patient collaboration with hundreds of the town’s inhabitants. They are young hands and old hands, hands accustomed to work, to care, to the distracted gesture of the passage of time. Aparicio collected their fingerprints one by one in markets, retirement homes, and clubs and turned them into 4,400 bronze tiles, cast individually, then assembled to make up the shiny surface of a bench.

An object to be inhabited, from which to look at the landscape. It is a silent resting place oriented toward the Koolhofput pond, in one of the places where the First World War front had opened a wound in the earth. To inhabit this work is not just to observe, but to connect with a silent multitude. The footprints envelop, protect, confuse. One is greeted by a web of bodies no longer present, but still legible in the metal. The title itself, “At Rest,” is both clear and layered: it refers to the gesture of sitting, but also to military command, to time yielding, to deposition. It is a work that does not promise eternity; on the contrary: it is built precisely so that time will wear it down. The hands that generated it will disappear, the weather will slowly wear away the lines, the grain will flake off, the edges will blur, and it is this, the gradual creasing of the surface, that will make it even more alive, more real. It is a memory that changes with the landscape, that ages with those who visit it in which the memory is entrusted only to time and the gesture of sitting, looking and staying. Even if only for a handful of seconds.

Yet there is also a memory that does not welcome, console or protect. It is a memory that archives, that preserves without understanding, that holds the signs of presence as anonymous remains. It is that which runs through the work of Christian Boltanski, a French artist who over the years has built one of the most radical contemporary reflections on the theme of disappearance, mourning, and erased and inaccessible identity. He works with what all remains, with common and seemingly anonymous objects, navigating in a language that is poor but charged with ritual intensity. His installations tell nothing but witness, and they do so without guarantees, without assuring that what we see can really be restored to life.

In works such as Les Archives, Boltanski displays rows of tin boxes that inside them present photographic artifacts, documents, fragments of his own studio, then sealed and made inaccessible. They are just unopened remains, inarticulate relics with no name or biography to consult. A pile of traces that can no longer be interpreted, a subtraction of order. His archives (from 1965-1988’s Les Archives de CB to 2001’s La Vie impossible ) record a desperate will to hold back the passage of men, while knowing that no gesture will ever again be able to reconstruct the full meaning of those remains.

With 2010’s Personnes, in that mountain of inert clothing that traveled from the Grand Palais in Paris to the Hangar Bicocca in Milan, Boltanski again works on despoliation by constructing an inaccessible geography of clothes piled up, torn from life, fished out casually.

“The photograph, the garment or the corpse of someone are practically the same thing,” he will say, “there was someone there, now he is no more.” Even the visitor, in front of these works, is not a privileged spectator, but a belated witness, for here memory becomes an obsessive gesture, useless and poignant. It is a fragile form of resistance, lacking faith in the possibility of transmission, but obstinate in continuing to accumulate, to record, not to forget.

In recent years, however, this tension is becoming lighter, more rarefied, and the material dissolves into sound, vibration, air. Les Archives du cœur, for example, collects human heartbeats, in which lives are heard, recorded, and inexorably lost.

In Animitas, on the other hand, it is the wind that is the protagonist, traversing hundreds of bells scattered across the Chilean Atacama desert, creating a concert of subtle voices and a very fragile bridge between earth and sky. As if, beyond history, beyond names, beyond bodies, this is what we are really made of. Of air, of sound, of memory that keeps escaping from our fingers.

It is a memory without myth that survives when there is no one left to interpret it. Then again, this is true for every cultural icon, and the legend, today, does not live on just because it is bigger or more important; it lives if someone decides to believe in it again, with awareness. And if that gesture does not happen, even the most meaningful apparition falls on deaf ears. It fades away. Perhaps, today, the question to ask is not why myths fade away, but rather where we are when they show up. Are we still able to recognize something that does not look like us, that does not speak to us in our own codes, that does not seek immediate consensus? In the end, perhaps the real challenge lies not in protecting the myths of the past, but in learning to let them happen in new ways knowing that sometimes, before the roar, there is silence, that not everything that is not embraced is lost, and that even a legend can appear and disappear unnoticed. And still remain.

Not because of what it represented, but because of what it can still teach those who, today, have the most difficult task: to recognize what does not resemble it and to keep it with them, even so. Even if it is uncomfortable, cumbersome and inaccessible.

The author of this article: Francesca Anita Gigli

Francesca Anita Gigli, nata nel 1995, è giornalista e content creator. Collabora con Finestre sull’Arte dal 2022, realizzando articoli per l’edizione online e cartacea. È autrice e voce di Oltre la tela, podcast realizzato con Cubo Unipol, e di Intelligenza Reale, prodotto da Gli Ascoltabili. Dal 2021 porta avanti Likeitalians, progetto attraverso cui racconta l’arte sui social, collaborando con istituzioni e realtà culturali come Palazzo Martinengo, Silvana Editoriale e Ares Torino. Oltre all’attività online, organizza eventi culturali e laboratori didattici nelle scuole. Ha partecipato come speaker a talk divulgativi per enti pubblici, tra cui il Fermento Festival di Urgnano e più volte all’Università di Foggia. È docente di Social Media Marketing e linguaggi dell’arte contemporanea per la grafica.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.