Some call it Kundalini, some identify it with the Dragon, and some consider it a cosmic principle. In some religious traditions it takes the form of the Ouroboros, a symbol of eternal return. Within our imagination, the serpent has always exercised a central role. An ambivalent animal par excellence, it embodies both attraction and repulsion, threat and wisdom. Its potentially lethal bite makes it an emblem of power, but also of duality: it alludes as much to temptation as to the possibility of metamorphosis. Throughout the millennia, the serpent has morphed into a mythological and religious figure and has taken on ever-changing but consistently contradictory roles: sometimes it is a demon, sometimes a guardian, a guide, or a bringer of sin.

But each time, it remains a sign of contradiction. And when one speaks of serpent and temptation, it is almost inevitable that the thought runs to Eve, seduced by the devil and banished from Eden along with Adam. In truth, before her, there is another female figure in ancient texts, often forgotten: Lilith. Considered the first woman, demon of the night and primordial rebel, she represents a powerful and uncomfortable archetype. To truly understand her connection to the serpent, it is necessary to go back to her origins.

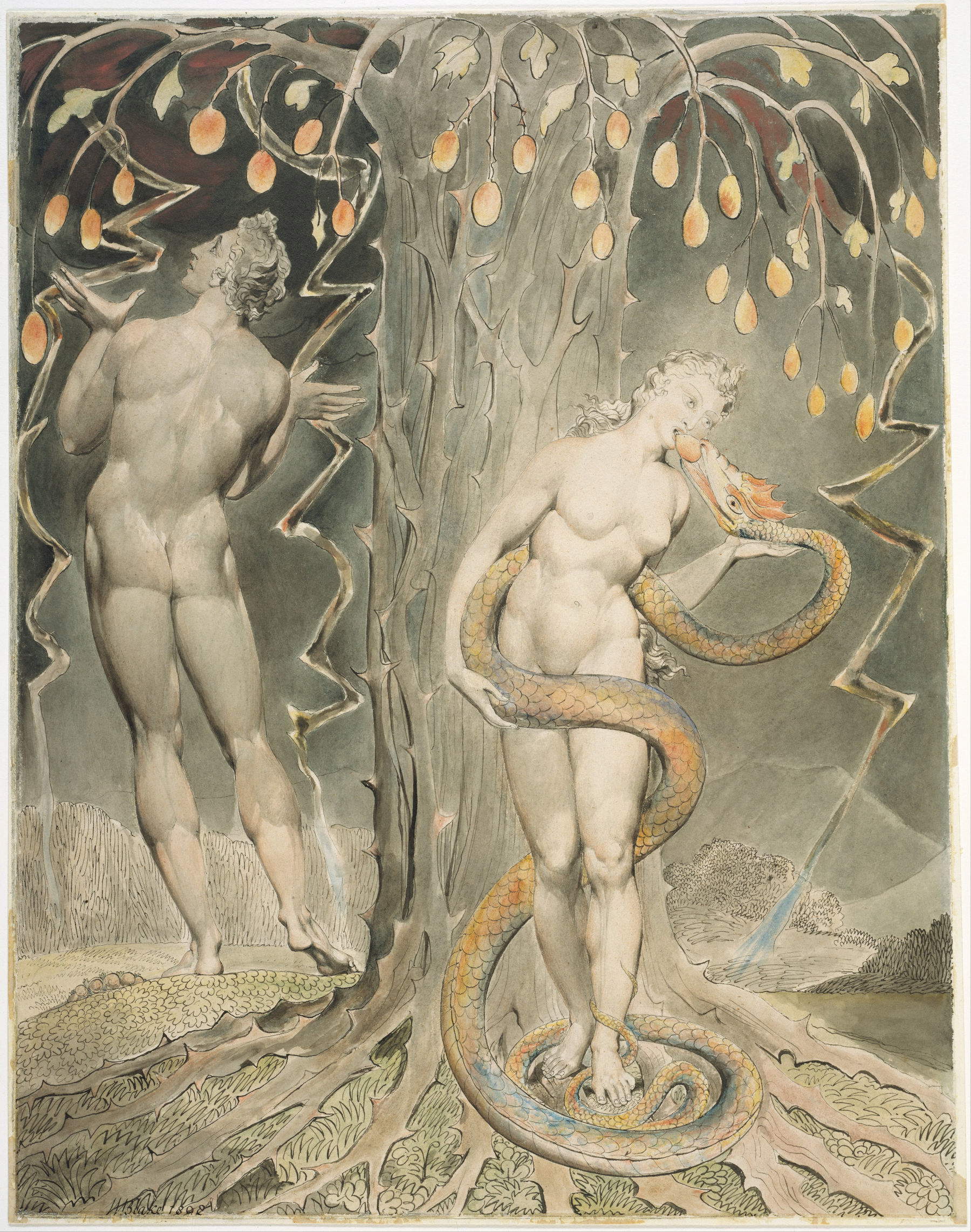

Her name already appears in Mesopotamian religious texts from the 3rd millennium BCE. Later, his legend is taken up and reinterpreted by Jewish tradition, particularly in the period of the Babylonian exile, when contact between different cultures gave rise to new worldviews and divine. In Mesopotamia, Lilith was seen as a female spirit linked to the most violent natural elements, particularly storms and stormy winds. She was indeed considered a dangerous presence, responsible for illness and misfortune.

Beginning in the 6th century CE, Jewish tradition began to mention Lilith in rabbinic texts and on ritual objects. In popular Jewish thought, the figure became a nocturnal demon feared for her ability to cause harm, particularly to male children. It was also associated with qualities considered negative in femininity, such as dark magic and lust. Well, all these aspects inspired numerous artists in depicting Lilith, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Collier in his 1892 painting.

In the latter’s work, the serpent envelops the female figure as an extension of her own body, suggesting a symbiosis between the woman and the animal. Collier, a Pre-Raphaelite British painter, thus draws on the archaic and ambiguous figure: Lilith is the embodiment of female seduction and independence, associated with the origin of sin and a sexuality unregulated by social or religious constraints. In medieval Jewish imagery, particularly in the Alphabet of Ben Sira, an 8th-10th century text, Lilith appears instead as Adam’s first wife, created from the same earth and therefore his equal, but rejected because she does not intend to submit. Having escaped from Eden, she becomes a demonic creature and thus a symbol of uncontrollable desire. Collier’s painting, now housed in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter , UK, thus translates the nakedness of the woman who is not vulnerable, but hieratic and distant. Lilith is algid. In her case, the serpent is not the symbol of temptation: it is a complicit figure, an allied creature.

Thus, we know that Lilith embodies an archetype found in the biblical narrative of Genesis. After her exclusion from the canonical account, it is Eve who becomes the paradigmatic figure of sin. According to Genesis 2-3, God forbids Adam and Eve to eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. “The serpent was the most cunning of all the wild beasts made by the Lord God” (Gen 3:1), and it is he who insinuates doubt and suggests transgression. Eve picks the fruit and hands it to Adam. The text, if read carefully, does not assign greater weight to the woman’s guilt, but theological interpretation, especially since St. Augustine, has built on the episode the idea of original sin as the foundational event of the human condition.

In the Confessions, Augustine argues that humanity inherits not only disobedience from Adam, but also an actual biologically transmitted guilt. The concept will profoundly influence medieval theology and the anthropological outlook of the West. Eve becomes primarily responsible for the Fall, and with her a long series of representations of the feminine as the cause of man’s loss of innocence and ruin is inaugurated. Female disobedience, understood as a desire for knowledge or autonomy, is crystallized in the serpent who whispers, deceives in order to deceive. One of the best-known depictions of the scene is the fresco Michelangelo painted on the vault of the Sistine Chapel around 1510. In the episode of Original Sin and Expulsion from Paradise on Earth, the artist concentrates all the tension of the forbidden act in a single dramatic image.

In the center of the composition, the tree of knowledge divides the scene into two distinct but contiguous moments: on the left, Eve plucks the fruit and receives it directly from the serpent; on the right, Adam and Eve are expelled from the garden by an angel armed with a sword. The serpent that Michelangelo paints is remarkable. The motivation? It does not have the usual appearance of a slithering reptile; rather, it possesses the body wrapped around the trunk is female at the top, with a human face and torso. It is a sibylline creature, androgynous and tempting, blending seduction, intelligence and transgression into itself, making the dynamic of guilt even more subtle and insidious. Could it be Lilith? Without a doubt. A more mystical and visionary reading emerges in William Blake’s 1808 The Temptation and Fall of Eve, made for illustrations in John Milton’s Paradise Lost. In the English painter’s work, Eve appears as a self-conscious figure, enraptured by a sense of mystery rather than transgression. The serpent, illustrated with twisted elegance, becomes a messenger of forbidden but necessary knowledge. Blake does not condemn, rather he shows the fall as a passage to consciousness.

Titian in his Adam and Eve in the Earthly Paradise, 1550, depicts the two progenitors in a crystallized moment. Eve holds out the fruit to Adam. The serpent, twisted in the tree, has a childlike body; it is in fact a child. In any case, the painting elicits mixed impressions: the vibrancy of the colors, especially in the landscape, clashes with a certain rigidity in the execution of the figures. Eve’s gesture comes across as unnatural, while Adam’s stringy body, modeled with excessive adherence to a sculptural prototype, appears unnatural. Such anatomical precision forced the artist to add fig leaves to cover his genitals, compromising the overall harmony of the composition. Aware of the limitations, Rubens significantly altered the scene in his version Adam and Eve in the Earthly Paradise (Original Sin): Adam’s pose was revised, orienting his body more to the side, in a position more similar to that revealed by the X-ray of the original work.

Different is the approach of Lucas Cranach the Elder, who painted several versions of the theme. In The Temptation of Adam and Eve (1526), the serpent takes the form of a woman-serpent with long blond hair, tracing the medieval figurative art of the serpent. The scene takes place in a serene landscape, but the tension is all in the gestures: Eve offers the fruit naturally, while Adam seems to hesitate. The temptation is silent and already happened. The female serpent’s body is a mirror double of Eve. What does it mean? That temptation comes from human nature itself.

In any case, the symbolism of the serpent has older and more complex origins. In Mesopotamian cultures, the snake was an emblem of life, regeneration, and wisdom. In Egypt, the goddess Wadjet, represented by a cobra, protected the pharaoh and embodied royal power. In archaic Greece, the staff of Asclepius, wrapped in a snake, was a sign of healing and knowledge (and is still used as a logo by the World Health Organization today). The snake also appears in the biblical account of the bronze serpent that Moses lifts up in the desert: those who look at it are healed from the bites of other snakes. Indeed, the purpose of Necustan, the name of the bronze serpent, confirms that the symbol may also have had therapeutic or protective value.

The gradual demonization of the snake occurs especially with the rise of Christianity. TheApocalypse of John defines Satan as “the great dragon, the ancient serpent” (Rev. 12:9), definitively establishing the connection between reptile and absolute evil. The association is then transmitted to the visual and literary culture of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, in which the serpent takes on increasingly sinister, often anthropomorphic connotations.

But the mythical figure that most radically combines serpent, femininity and guilt is perhaps Medusa (here for focus on Medusa). In Greek mythology, Medusa is one of the three Gorgons, and the only mortal. Her myth evolves over time. In older versions, Medusa is a chthonic deity linked to the earth and fertility. Only later does she become the monster who petrifies those who look at her, with snakes for hair. According to Ovid and his Metamorphoses, Medusa was a young priestess of Athena who was raped by Poseidon in the goddess’ temple. In response to the outrage, Athena punished her by turning her into a monster, not her attacker. Here again, as in Eve or Lilith, the feminine is punished for an act that straddles the line between transgression and overpowering.

The face of Medusa, fixed in Perseus’ shield and in apotropaic depictions, is at once terrible. It begins with the idea that horror (given by snakes), in order to be endured, must be channeled into a visual form: asymbolic effigy, or eikón, capable of containing terror and banishing theeidolon, the specter. The Medusa becomes the embodiment of the figure: an ancestral creature whose gaze is directed not at the living but at the dead, to protect or repel them. Its ability to petrify is also an extreme form of defense. In the Dialogues of Lucian of Samosata, Medusa is evoked as a symbol of beauty capable of immobilizing, dominating, subduing. Over the centuries, the figure of Medusa will be reinterpreted in a more psychoanalytic and feminist reading. Sigmund Freud, in his 1922 essay DasMedusenhaupt (Head of Medusa), reads the face of the Gorgon as a representation of the trauma of castration. Simone de Beauvoir, in her critique of the structural misogyny of myth, sees Medusa as the victim of a patriarchal culture that transforms fear of women into monstrosity.

In modern and contemporary art, Medusa has been reevaluated as an emblem of resistance. In Arnold Böcklin’s 1878 Medusa, the Gorgon is no longer a monster, but a woman with a sad and self-conscious face. In 2008, Luciano Garbati’s sculpture Medusa with the Head of Perseus, an inverted reinterpretation of Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus with the Head of Medusa , shows Medusa holding the head of the hero who decapitated her, turning the victim into an agent.

In the confrontation between Lilith, Eve and Medusa, a red thread emerges: the snake, from a real animal, turns into a symbol. It represents the enigma, the threshold, the passage between two states. It seduces to guilt and knowledge, to freedom, to rebellion. The three female figures share the fate of being narrated as the origin of disorder, evil, or the crisis of a system. And all, over time, have been rediscovered as alternative possibilities for reading power, desire, and female identity. The serpent, then, is a figure of language and metamorphosis. In the Bible, myth, painting and psychoanalysis, it crosses the realms of faith, philosophy and cultural history, and remains, to this day, one of the most ambiguous emblems of Western civilization.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.