Entitled The Women’s Burden. On the tracks of a feminine neo-expressionism is the latest chapter in the critical rediscovery of Valeria Costa (Rome, 1912 - 2003), a painter whose artistic career is at the center of growing attention: it is an exhibition, curated by Valentina Gioia Levy and Pier Paolo Scelsi, which is hosted in the rooms of Palazzo Contarini del Bovolo from February 16 to April 28, 2019, and which intends to focus on the works that Valeria Costa created between the late 1960s and the early 1980s. Little more than a decade, then, but fundamental for the career of the artist who, in those years, abandoned the crude realism in the furrow of which she was formed and which echoed the painting of the greats of the Neue Sachlichkeit, the New Objectivity of German art of the 1930s.

It was precisely in the 1930s, in fact, that Valeria Costa’s career had begun, after training at the Academy of Fine Arts and the nude school in Rome. At first Valeria Costa worked as a costume and stage designer, collaborating with the Compagnia dell’Accademia that had been created by the theater critic Silvio D’Amico (Rome, 1887 - 1955) and that experienced a first, successful season between 1939 and 1941, only to be refounded after the war (and its activities continue to this day). Valeria came, moreover, from a family of art: her brother was the great Orazio Costa (Rome, 1911 - Florence, 1999), a celebrated theater director, among the greatest of the early postwar period (he founded the Piccolo Teatro della Città di Roma in 1948, was director of Teatro Romeo for ten years, worked with actors of the caliber of Nino Manfredi, Marina Bonfigli, Rossella Falk, Gianrico Tedeschi, and was a teacher of a long line of younger actors: Pierfrancesco Favino, Claudio Bigagli, Alessio Boni, Luigi Lo Cascio, Fabrizio Gifuni, among them). Work with the theater would accompany Valeria Costa throughout her career, since for a long time she continued unceasingly to make costumes for her brother’s plays, but her approach to painting was also precocious, so much so that already in 1939, at only twenty-seven years old, she was able to exhibit at the third Quadriennale in Rome.

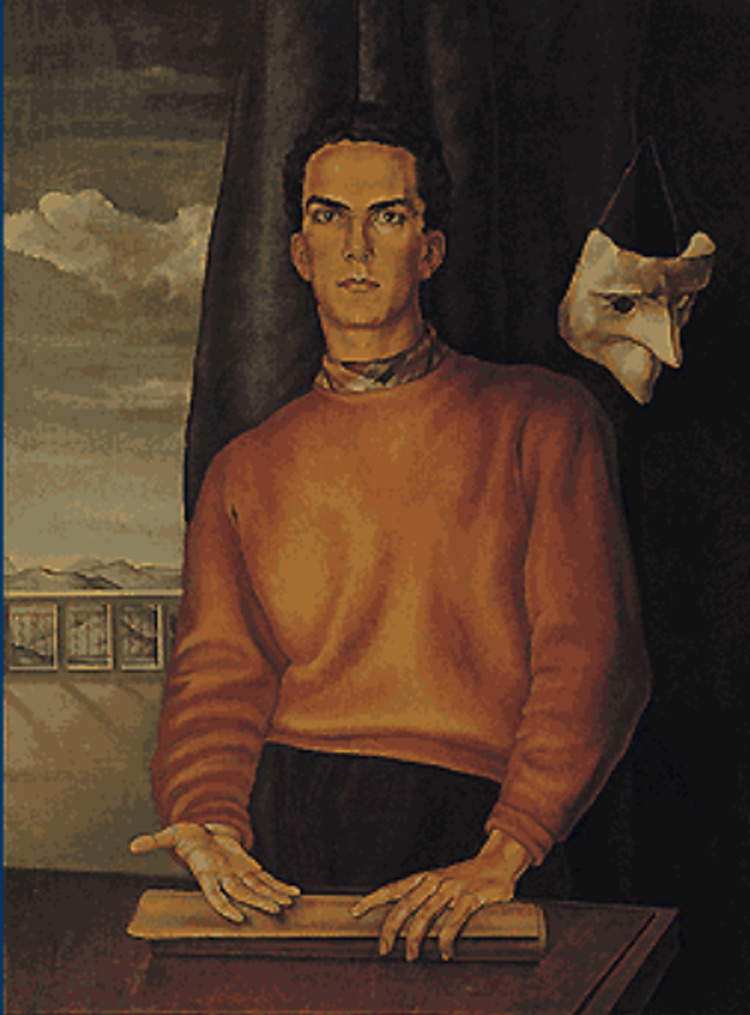

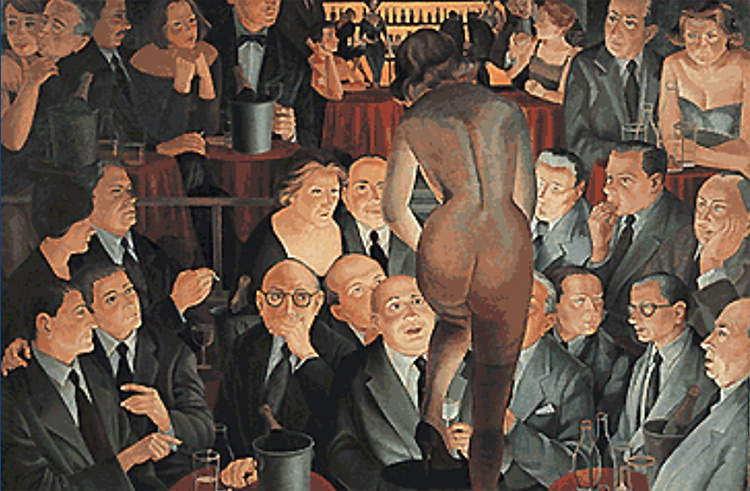

Scrolling through the archives of that edition of the important Roman exhibition, one can find her name alongside those of some of the greatest masters of the 20th century, from Giacomo Balla to Afro, Leonardo Dudreville to Achille Funi, Lucio Fontana to Mario Mafai, Giorgio Morandi to Renato Guttuso. Valeria participated with a Portrait that manifested her adherence to the stylistic features of the Roman School as well as her closeness to the Neue Sachlichkeit. Realism of a German matrix was the hallmark of Valeria Costa’s first twenty years of activity: austere portraits of friends and family abounded, in a certain way indebted to the portraiture of Alexander Kanoldt (the Portrait of Horace of 1939 could be cited above all), but also scenes of the Rome of the Dolce Vita (the Striptease of the 1950s), which revisited in a more lighthearted and disengaged key the alienating urban scenes of Otto Dix. It was, however, an affirmation that would have little follow-up, because in the following years her public commitments would be absorbed almost exclusively by the theater, and painting remained for Valeria Costa a passion to be exercised in private, so much so that there were those who believed that the artist had begun to paint at a very advanced age.

|

| Valeria Costa |

|

| Valeria Costa, Portrait of Horace (1939; oil on canvas) |

|

| Valeria Costa, Striptease (1950s; oil on canvas) |

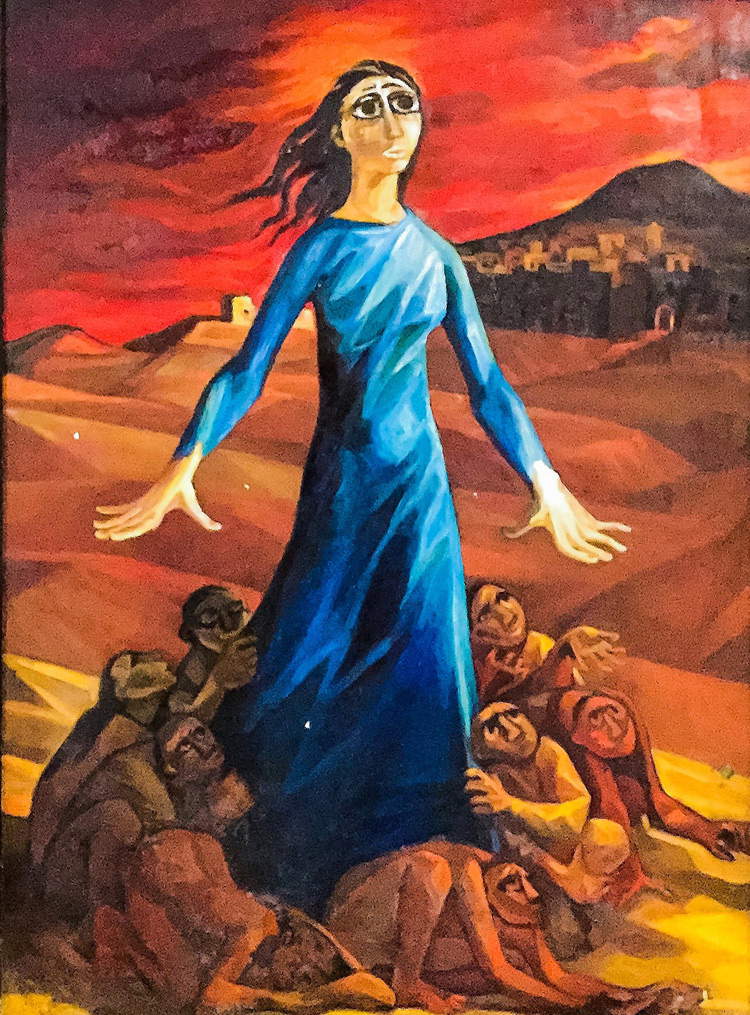

As anticipated, the beginning of the 1960s marked a decisive change of pace, in the totally opposite direction: abandoning the realism of her beginnings, Valeria Costa turned to an equally crude neo-expressionism that represented almost a unicum, since it was purely male painting. On the contrary, the Roman painter adhered firmly to the fury of neo-expressionism, adopting strong hues for the violent, angular figures that populate the body of work devoted to human suffering: to the chromatics typical of the Roman School and founded on warm, earthy tones (from carmine to ochre via sand) he combined the broken and dynamic forms typical of expressionist painting, to give substance to his own visions that declined the theme of pain in a purely feminine key (between the 1960s and 1970s, in particular, Valeria Costa produced two series of paintings whose almost exclusive protagonists were, precisely, women). They are heartbreaking and harrowing visions, where anguished figures move against the background of red skies and seem to want to transmit their anguish to the surrounding landscape as well, as happens, for example, in La Veronica, a painting that revisits the Gospel episode in an original way: we see the woman protagonist of the sixth station of the Way of the Cross as she runs, we are not sure why, with the veil, her typical iconographic attribute, in her hands, almost as if she wants to run away (and the artist has imparted such dynamism to the scene that even the tree behind her seems to want to chase her).

The figure of Veronica herself appears distorted, deformed in her anatomical proportions, and the same goes for what is with her in the setting. Critics have suggested that the pain that crusheshumanity, in Valeria Costa’s works, appears so aggressive that it has turned human beings into monsters and in turn into other monstrous beings what surrounds them: a furious struggle ensues where everyone is a victim. This is also true of other works of the same period, such as The Massacre of the Innocents, or the more lyrical but no less vehement Jerusalem, Jerusalem.

|

| Valeria Costa, La Veronica (ca. 1970; oil on canvas) |

|

| Valeria Costa, The Massacre of the Innocents (ca. 1970; oil on canvas) |

|

| Valeria Costa, Jerusalem Jerusalem (ca. 1970; oil on canvas) |

In the meantime, Valeria Costa’s exhibition activity was waning, but it would only resume with some frequency from the 1990s onward: in particular, one recalls the solo exhibition at the Complesso Monumentale di San Michele a Ripa in 1992, and especially the retrospective held in 2002, when the artist was now in her nineties, at the Vittoriano (and in the same year another exhibition was organized at the Galleria L’Ariete in Bologna). Valeria Costa had not, however, stopped experimenting: her latest research was in fact aimed atabstract art (in particular, the painter tried her hand at informal abstractionism and geometric abstractionism), while also being fascinated by surrealism. It was above all her numerous trips abroad from the 1960s onward that affected the further evolution of her art: sojourns in America directed her toward informal art, while those in Asia and Africa (especially North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa) helped introduce into her production the certain degree of primitivism that characterizes some of her abstract productions.

Given the purely private dimension of her painting, Valeria Costa’s name is certainly not among those best known to the public. However, recently the family has started a fund, the Valeria Costa Piccinini Heritage Fund, which aims to spread awareness of her art and enhance it in Italy and around the world. That left by Valeria Costa is a huge patrimony: to get an idea, it is necessary to consider that in 2002, a year before her death, she left a nucleus of one thousand two hundred works to the Alberto Sordi Foundation, later repurchased by the Valeria Costa Piccinini Heritage Fund with the aim of preserving them and making them known to the world.

This objective is also met by the exhibition The Women’s Burden, which, as anticipated, finds space in the exhibition halls of the monumental complex of Palazzo Contarini del Bovolo in Venice(more information at this link) and focuses on the artist’s neo-expressionist phase, “privileging,” as the presentation states, “ the works from which the suffering of women emerges in all its forms: a theme very dear to Costa. Birth, motherhood, family, death, war, fear, defense, are the key words that inspire this selection of paintings that will build a sort of Dantean path to the feminine.” For Valeria Costa, one more step on the path toward rediscovery.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.