How was the Parthenon illuminated? A distant question that has fascinated scholars for centuries finds new answers thanks to research published by theUniversity of Cambridge. The study, led by Juan de Lara(University of Oxford and University College London), completely reinterprets the lighting dynamics of the temple in Athens through an advanced methodology based on three-dimensional models and physical simulations of light. The results radically change our understanding: far from being a marble space flooded with light, the Parthenon interior was mostly a dark environment where a few, calibrated lighting effects transformed the vision of the statue of Athena into anepiphanic experience.

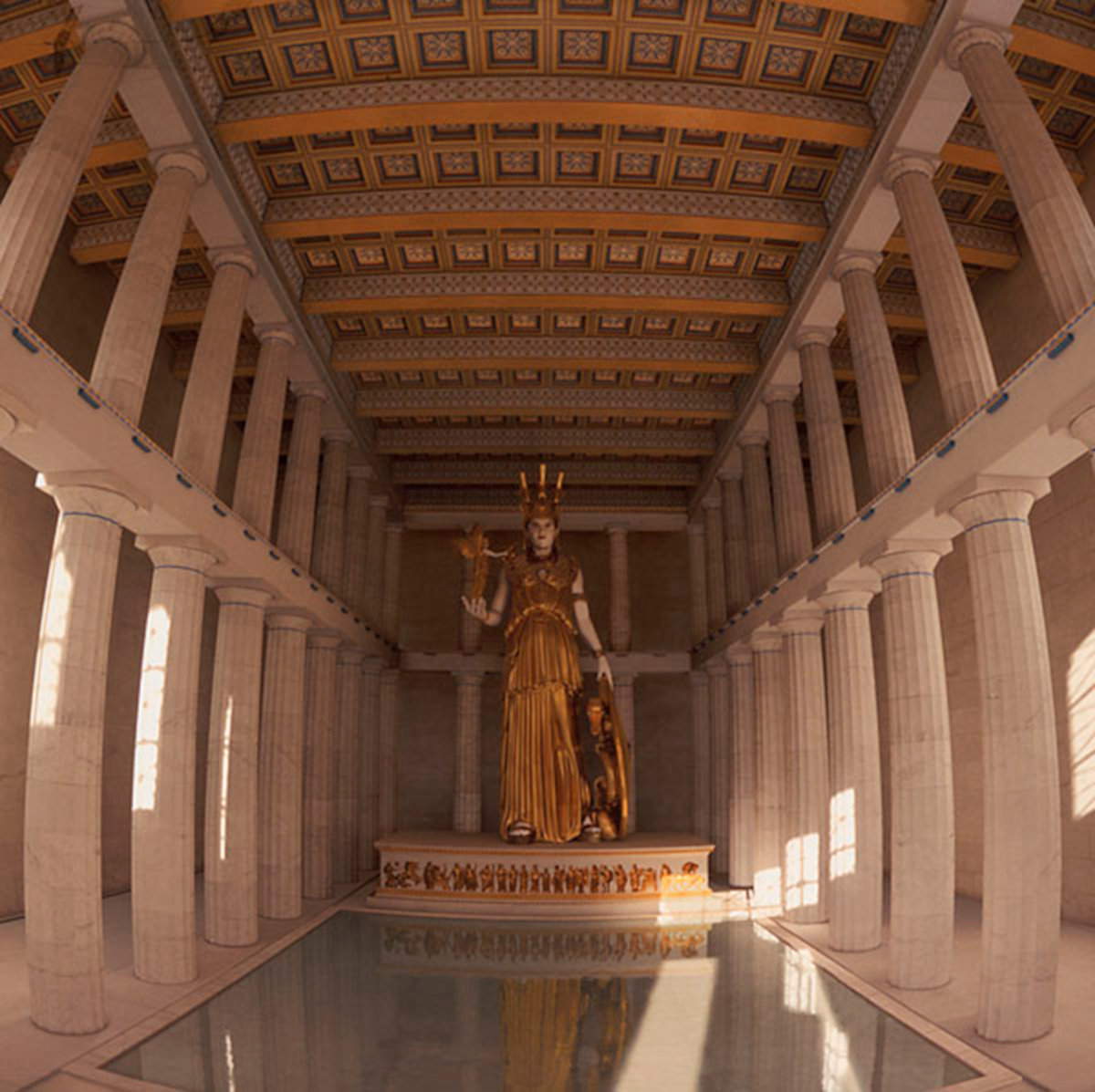

The temple, a symbol of classicism, was designed with pinpoint attention to controlling light. Oriented to the east to catch the first rays of the sun, it was equipped with side windows, skylights, perhaps translucent roofs, and, surprisingly, even a reflecting pool. Everything was designed to enhance the Chrysoelephantine statue of Athena made by Phidias: gold and ivory shining, sometimes in the glow of a single lamp, sometimes under a perfectly aligned blade of sunlight.

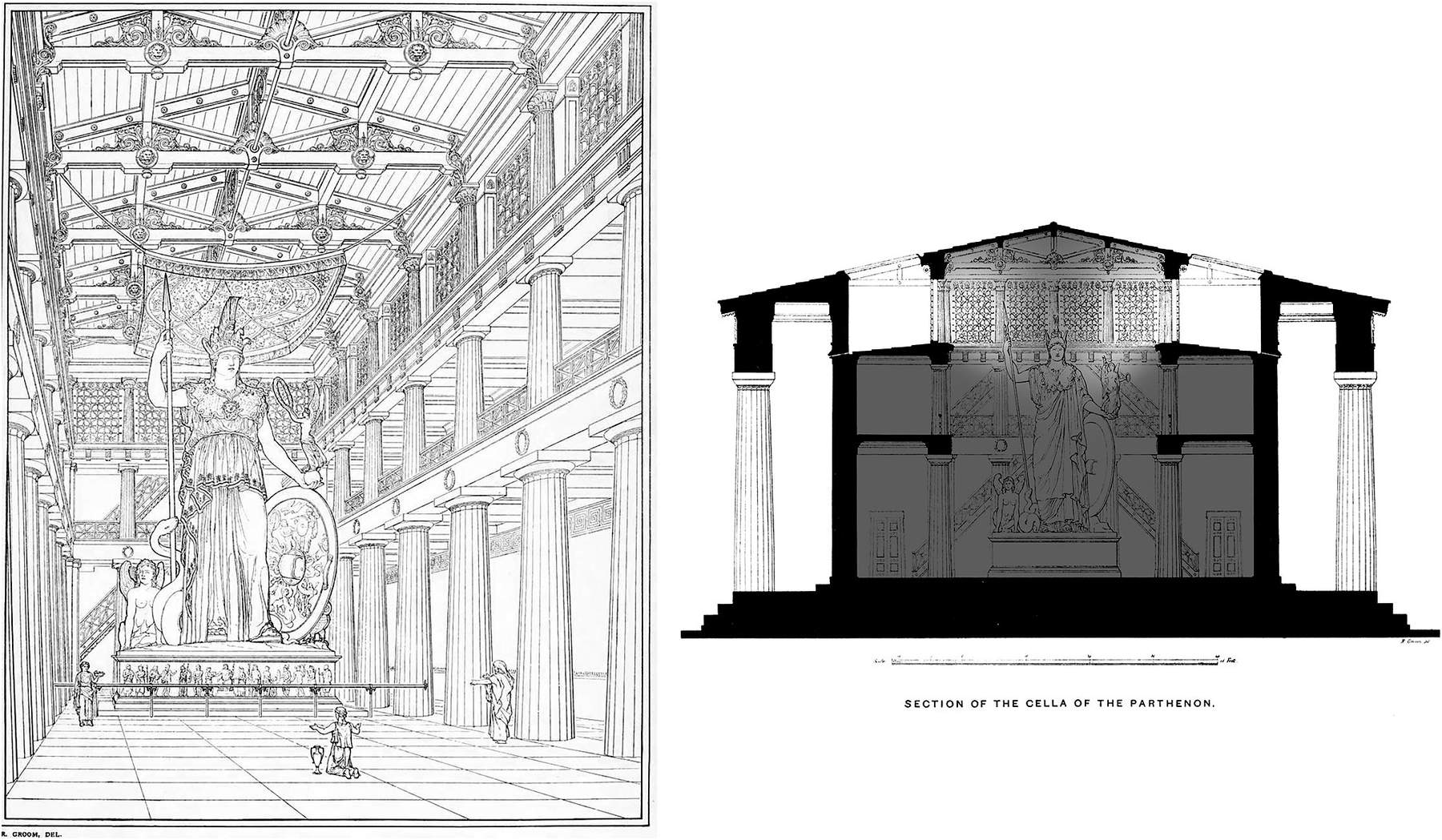

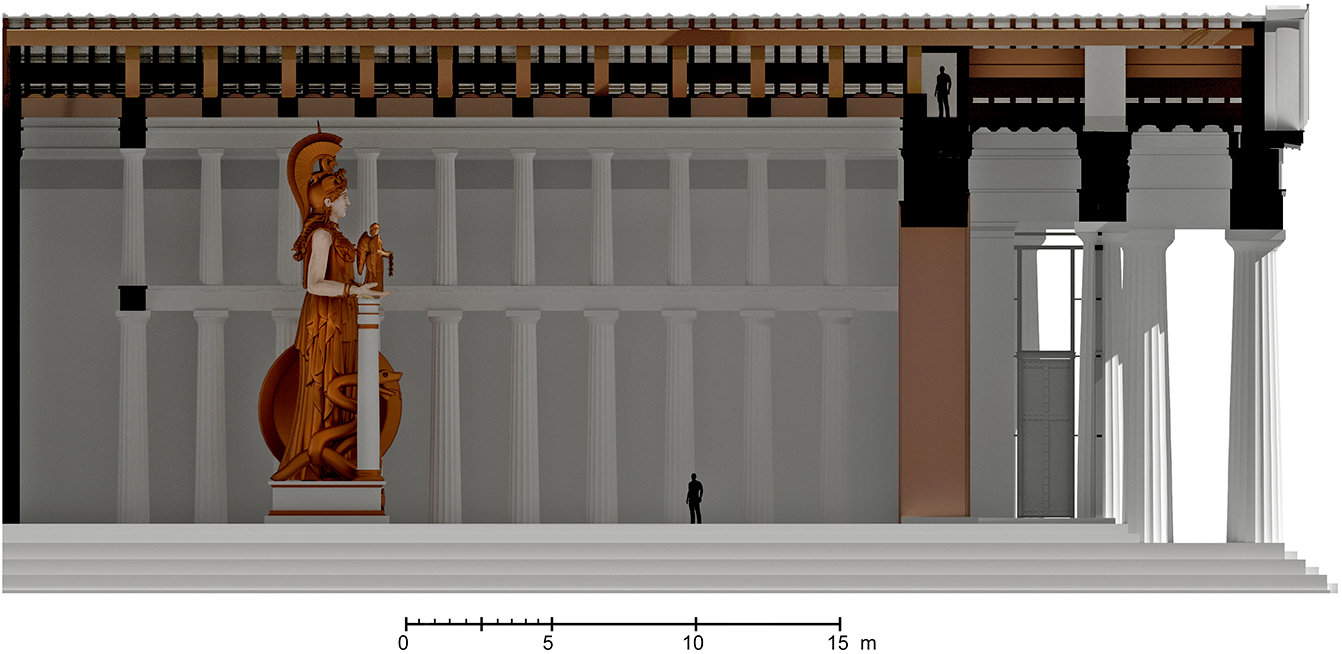

De Lara’s research starts right here: how to assess the actual effectiveness of these ancient devices? Classical sources, from Vitruvius to Pausanias, present fragments, and archaeology adds clues. But only modern technology can return a coherent picture of the temple. So the project digitally reconstructed the Parthenon, integrating every known detail: marble thicknesses, openings, reflections, votive objects, even the contents of the cella. The simulations, based on physically corrected renderings (PBR), showed how light really behaved inside. It emerged that lighting from the main entrance was limited, shielded by the porch and wooden barriers. Morning light, while symbolically important, illuminated the statue only on particular days or conditions. Fundamental, however, turned out to be other tools: side windows, considered by many to be marginal, allowed instead to illuminate the side rooms, where precious votive offerings and perhaps even a now-lost pictorial decoration were displayed. And again: the roof, according to some, was composed of Parian marble tiles, selected for their translucence. However, archaeological evidence points to the predominant use of Pentelic marble, which is less transparent.

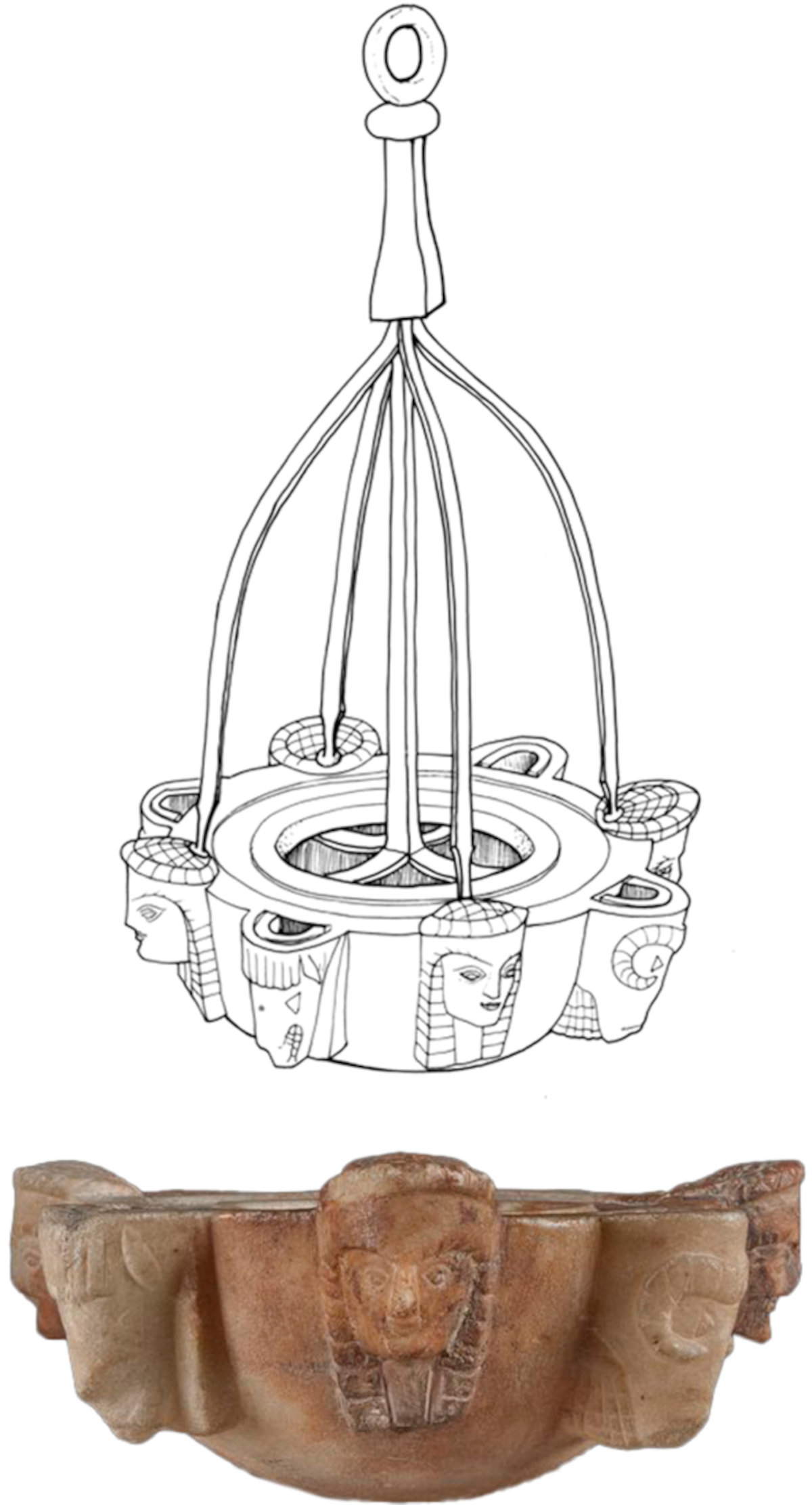

A key element of the lighting system was the water basin documented by Pausanias and confirmed by archaeological evidence. Positioned in front of the statue, it served, perhaps, to regulate humidity, but also, according to some scholars, to reflect light upward. Recent experiments confirm that the mirroring effect was possible, especially if the bottom of the basin was made of dark stone, as in the temple of Zeus at Olympia. The light reflected on the gold and ivory of the statue would have generated a dazzling vision, a divine apparition, a thauma, that is, sacred wonder, as reported by ancient writers.

The role of the lamps has also been reconsidered. Sources rarely mention them, but the most accepted hypothesis today is that of a symbolic and solitary “eternal flame” placed near the statue. We are not referring to a widespread system of illumination, but rather to a single point of light, charged with religious significance. As in the Roman tradition of the goddess Vesta or the Jewish culture of the ner tamid, the Parthenon may also have housed an ever-burning lamp, an emblem of divine presence. In any case, de Lara’s contribution is not limited to technical reconstruction. The study also analyzes two centuries of hypotheses and models, from Quatremère de Quincy to Fergusson to the physical reproductions of the 19th and 20th centuries, such as the Nashville Parthenon or the maquettes of the Royal Ontario Museum. The models, often interpreted with excessive light optimism, did not take into account factors such as the absorption of light by materials or the absence of reflective surfaces. Digital simulation then allowed these distortions to be corrected, returning a more faithful (and darker) image of the interior.

The implications of the research are broad, both for the history of ancient art or architecture and for understanding religious experience in the Greek world. The Parthenon, like other temples, was a sacred space where light, form and matter conspired to create an encounter with the divine. Darkness thus resulted as a well-defined choice. Light was metered, concentrated, focused-a beam that lit up the Athena only at certain moments.

|

| How was the Parthenon illuminated in ancient times? New research rewrites the history of the Greek temple |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.