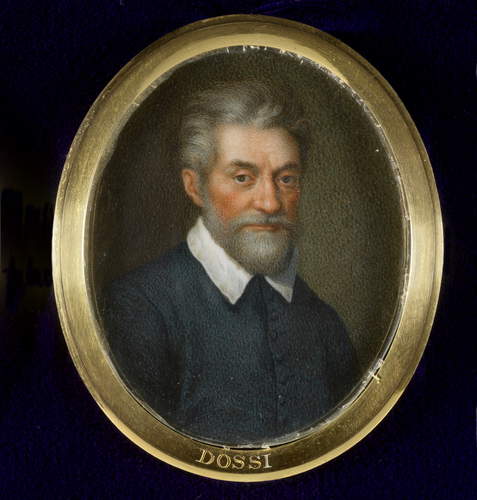

Dosso Dossi (Giovanni Francesco di Niccolò Luteri; Tramuschio?, c. 1486 - Ferrara, 1542) is one of the leading artists of sixteenth-century Emilia, a leading exponent of the so-called “fantastic strand”: an artist who loved to “fish” his subjects from myth if not even from the “witchy,” using an adjective used by scholar Mauro Lucco to describe his almost magical abilities(read an in-depth study of Dosso Dossi’s magic-themed paintings here).

We know little about his origins (we do not even know where he was born), but we do know that in the early 16th century he was the principal artist of the Este court in Ferrara, and he is the painter who is automatically associated with the magical and imaginative images of Ludovico Ariosto (both worked in Ferrara in the same years). Giorgio Vasari, too, in his Lives, juxtaposes Dosso Dossi and Ariosto: “Together with the gift that the fati de la Natività del divino Messer Lodovico Ariosto made to Ferrara,” writes the great historian from Arezzo, “accompanying the pen to the brush, they wanted Dosso the Ferrara painter to be born again; who, if he was not so rare among painters as Ariosto was among poets, he also did many things in art, which are celebrated by many, and in Ferrara above all. Hence he deserved that the poet, his friend and servant should make his memory honored in his very clear writings. Di maniera che al nome del Dosso diede più nome la penna di Messer Lodovico universalmente, che non avevano fatto i pennelli et i colori che Dosso consumò in tutta sua vita, ventura e grazia infinita di quegli che sono da così grandi uomini nominati.” His interpretation of myth and literature, his inimitable flair, and his visionary and imaginative images make Dosso Dossi one of the most interesting artists of the 16th century.

We do not know exactly where Dosso Dossi was born: the earliest document to start with concerns his father, dating from 1485, and says the parent resided in Tramuschio, a small town near Mirandola, at the time the capital of an autonomous state squeezed between the Marquisate of Mantua and the Duchy of Ferrara. Dosso, who may have been born probably around this year, was actually named Giovanni Francesco di Nicolò Luteri and was the son of Nicolò di Alberto di Costantino Luteri, who by profession was a “spenditore,” or bursar, at the court of Ferrara (although he was of Trentino origin) and Jacopina da Porto. The nickname by which he is universally known is said to derive from the fact that Niccolò Luteri owned a farm in the locality of Dosso Scaffa (today San Giovanni del Dosso, in the lower Mantua area). Dosso had a brother, Battista Dossi (Battista di Niccolò Luteri), with whom he had the opportunity to collaborate several times. Of his childhood and early years we know very little: his training can be inferred only on the basis of the style of his works. He certainly had the opportunity to observe the masters of the 15th-century Ferrarese school, and he also studied the works of the great painters of the Veneto, above all Giorgione. He also had a chance to look at the art of Raphael.

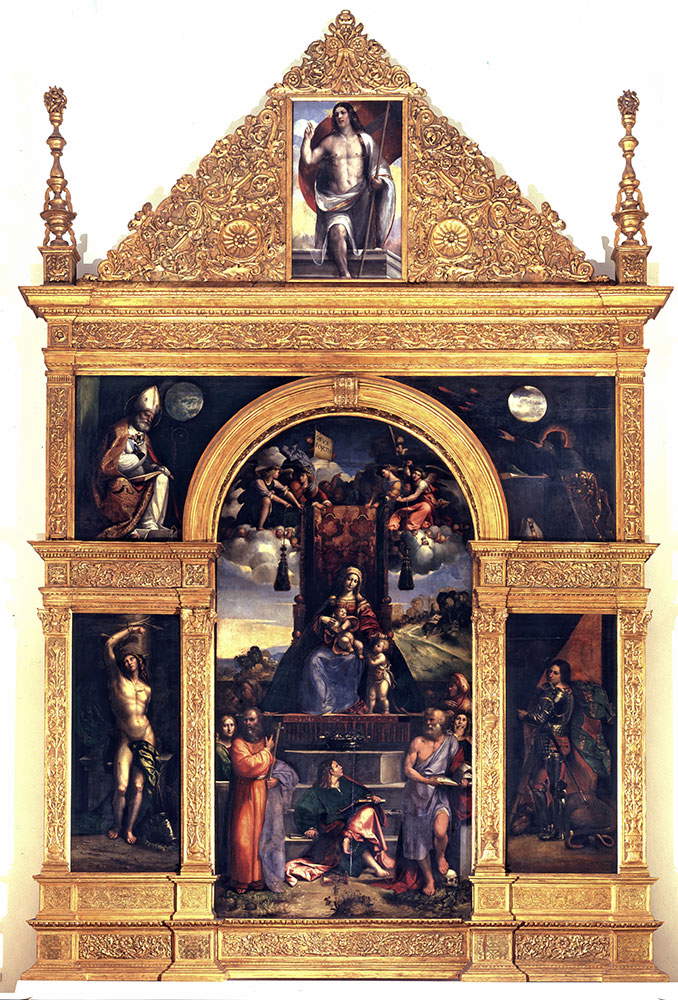

The first document directly traceable to Dosso dates back to 1512: it is a payment note dated April 11 for a “large painting with eleven figures” for Palazzo San Sebastiano in Mantua, at the time the residence of Francesco II Gonzaga di Arco (this is a painting we do not know about). Also in the same year another document attests to it in Mantua. Following the Mantuan “trail,” it might also be plausible to imagine that the artist trained in this city, perhaps studying under Lorenzo Costa, who became the Gonzaga’s court artist after the death of Andrea Mantegna (Vasari in fact says that Dosso was a pupil of Costa). On the stylistic basis, however, it is possible to imagine a Venetian training. In 1513, Dosso Dossi (referred to as “di Mirandola” in one document) was paid along with Benvenuto Tisi known as il Garofalo for the polyptych in the church of Sant’Andrea in Ferrara, which was finished the following year: this is the celebrated Costabili Polyptych, one of his most famous works, now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Ferrara. In 1514 he is registered as a court artist with the Este family: from this year on, the account books of the Castello Estense will indicate the presence of a strong link between Dosso and the court (the artist, however, did not receive a salary, but was paid by assignment: a “precarious” one, we would say today, but the advantage lay in the fact that he was free to work for other patrons, as indeed he would do, and with great success, being one of the leading artists in northern Italy of his time).

As a court painter, Dosso Dossi made several trips, between 1516 and 1518, to Venice (where he went several times, mainly to procure material) and to Florence: during these trips he was able to deepen his knowledge by studying, for example, the art of Titian. In 1518 he received a commission for the altarpiece for the altar of San Sebastiano in Modena Cathedral (still in the place for which it was painted), while in 1519 he met with Titian: together the two painters went to Mantua to see the collection of Isabella d’Este. Further commissions for the Este family date from the following years, and also in the 1920s he obtained many commissions for local churches, often executed in collaboration with his brother Battista. In 1530 the two brothers stayed in Pesaro to attend to the decorations of the Villa Imperiale, commissioned by the duke of Urbino, Francesco Maria I Della Rovere. Later, between 1531 and 1532, Dosso and Battista were in Trento to work on the fresco decorations of the “Magno Palazzo” in the Castello del Buonconsiglio, commissioned by Cardinal Bernardo Cles, bishop-prince of Trento. The artist returned to Ferrara in 1532 and went back to work for Alfonso d’Este, although after the latter’s death and the rise to power of Ercole II the new ruler’s tastes veered toward other artists: however, Dosso Dossi was entrusted with the renovation of the delizia of Belriguardo. The last works he executed for the Este were commissioned from him in 1540: they are the San Michele and San Giorgio that are now in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden. The artist disappeared in Ferrara in the first half of 1542.

A whimsical, imaginative, eccentric artist with an unparalleled narrative verve and a great ability to interpret secular subjects (particularly mythological and literary ones), Dosso Dossi is best remembered for his paintings with fantastic themes, but his long career led him to successfully express himself in a wide variety of genres. Dosso Dossi moved between the tonalism of Giorgione, the classicism of Raphael, and the eventful Titianesque painting, and already during his lifetime he was considered one of the greatest masters of his time partly because of his ability to look at the natural world with an intensity ahead of his time, sometimes even pre-Caravaggesque. Dosso Dossi’s first important work in which his style appears already delineated (so much so that it was considered a mature work, before it was discovered that it was a 1513 painting) is the Costabili Polyptych, painted for Sant’Andrea in Ferrara and now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in the Emilian city: a modern work distinguished, the scholar Peter Humfrey has written, by “the warm, rich colors, the poetic atmosphere created by the nocturnal or twilight light, and the evocative breadth of the pictorial treatment,” features that make clear its links with Venetian painting and in particular that of Giorgione. The fact that the Madonna’s impression is reminiscent of Raphael’s Madonna di Foligno has led scholars to speculate on Dosso Dossi’s trip to Rome as well.

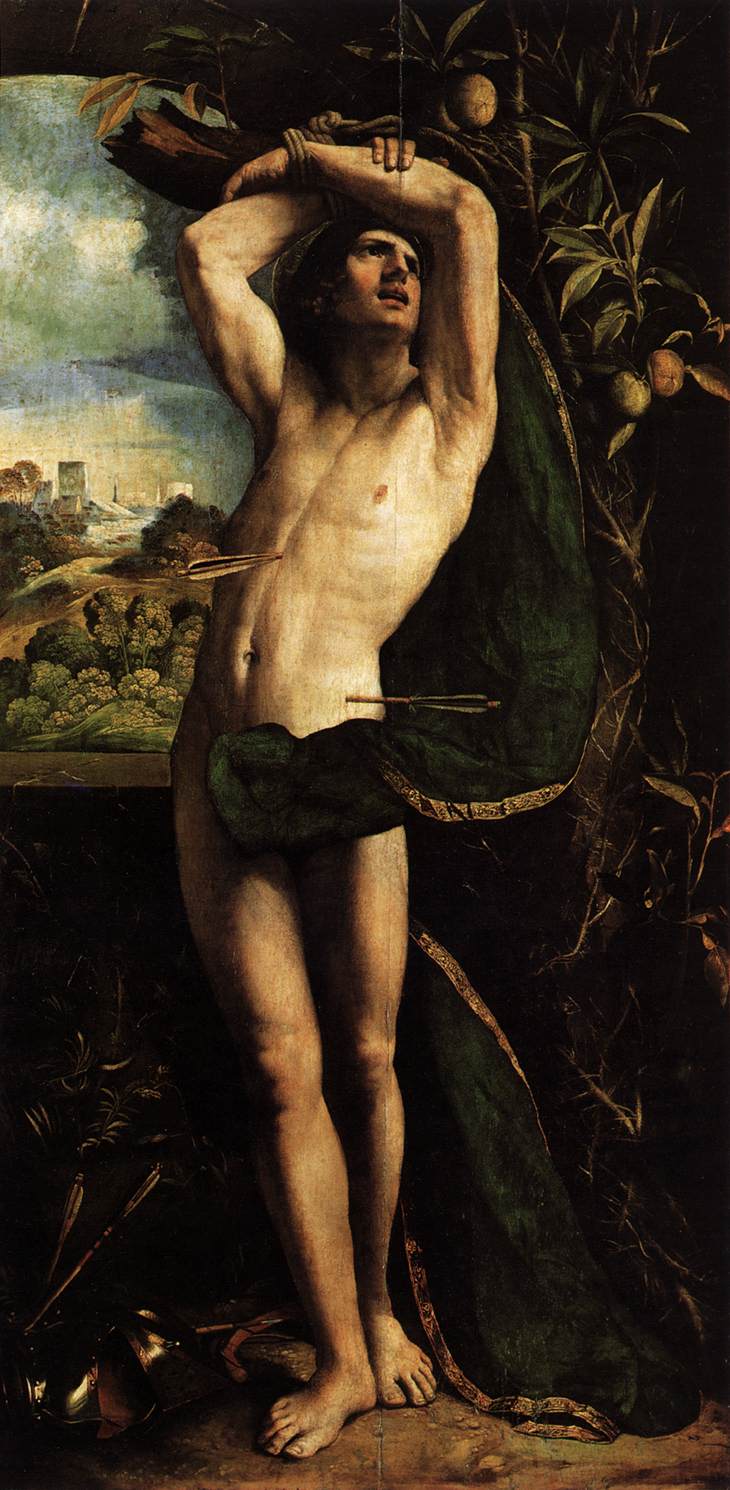

A fixed point in Dosso Dossi’s chronology, the Costabili Polyptych is followed by paintings in which some grand, sensual, natural-looking figures dressed in flamboyant robes are immersed in verdant landscapes: this is the case with the Melissa, one of the paintings that best exemplify Dosso Dossi’s “magical” style and that best convey the artist’s taste for extravagance, imaginative settings, and vivid color solutions. The Melissa is from about 1518: They also reflect this exuberant taste in other works of the same phase that deal with other themes, such as the religious (the San Sebastiano of the Pinacoteca di Brera, dated 1518-1521, which reflects Dosso Dossi’s interest in Michelangelo Buonarroti, combined here with typically Venetian elements) and such as the mythological(Pan and the nymph, a rich and luxuriant allegory of c. 1524, where the viewer’s attention is captured by the sumptuous female nude in the foreground; theApollo of the Galleria Borghese, which is perhaps the most luminous example of Dossi’s classicism, with the figure of the god of music harking back very clearly to the Belvedere Torso).

The works that Dosso produced in collaboration with his brother Battista are the weakest of his output, although, Peter Humfrey has warned, it is not necessarily the case that the less strong works in Dosso’s catalog are necessarily attributable to his collaboration with his brother. In fact, Dosso used several collaborators, and it is often difficult to distinguish the hands in the weaker works. However, we know for certain from documents that the two brothers collaborated on theAllegory of Justice now in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden (Battista was paid for the work in 1544). The figures appear “stiff,” Hunfrey writes, characterized by “sausage-like fingers; foreground elements done in a descriptive and pedantic manner; tree canopies done with flat, decorative leaves; a misty, generically dossy background with clusters of buildings and unlikely vertical rocks; a bland, uniform treatment with bright colors.” In the last works of his career, Dosso Dossi did not stop innovating, and this is clearly seen, for example, in the Allegory of Hercules in the Uffizi, where the artist even launches into an almost pre-Caravaggesque realism, veined with irony, for a result that would only be seen much later in the course of the 16th century, in the works of artists such as Annibale Carracci, Bartolomeo Passerotti and Vincenzo Campi. “Dosso’s last works of this type, far removed from the predominant Titianism of his early maturity,” Humfrey wrote, “show that not only did the painter remain active until the end of his life, but also that he never stopped expanding the boundaries of his art in ways that would inspire future generations of artists.”

With the Devolution of Ferrara, or the handover of the dominions of Ferrara to the Papal States (1598), the works of Dosso Dossi that were in the city were mostly dispersed. However, in the city you can see his first important work, namely the Costabili Polyptych, now at the National Picture Gallery of Ferrara, which is located inside the Palazzo dei Diamanti. There are no museums that hold substantial nuclei of Dosso Dossi’s works, but there are nonetheless institutions where important masterpieces can be admired, often together: this is the case at the Galleria Borghese in Rome, where the Melissa and theApollo are located, as well as several other paintings. In the Cathedral of Modena, on the other hand, it is possible to see the Saint Sebastian Altarpiece, still placed in the place for which it was made. Other works by Dosso Dossi can be found, in Italy, at the Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti, Fondazione Cini in Venice, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Pinacoteca Civica di Forlì, and Galleria Nazionale di Parma.

Abroad, works by Dosso Dossi can be found at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the National Gallery in London, the Metropolitan in New York, the Louvre, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, the National Gallery in Washington, and the Wavel Castle in Krakow (Dosso Dossi’s most famous work found outside Italian borders, namely the Jupiter Painter of Butterflies, is preserved here).

|

| Dosso Dossi, life and works of the sixteenth-century magical artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.