To speak of Impressionism and Impressionist painters and sculptors is to recount one of the most well-known events in the history of art, as well as one of the most appreciated: to this day, Impressionist exhibitions rank among the most beloved and well-attended by the public. But who were the Impressionists and why was their contribution so fundamental to art history? What was the revolution they introduced, so much so that they created a kind of caesura between the before and after? Who were the main protagonists of this revolution?

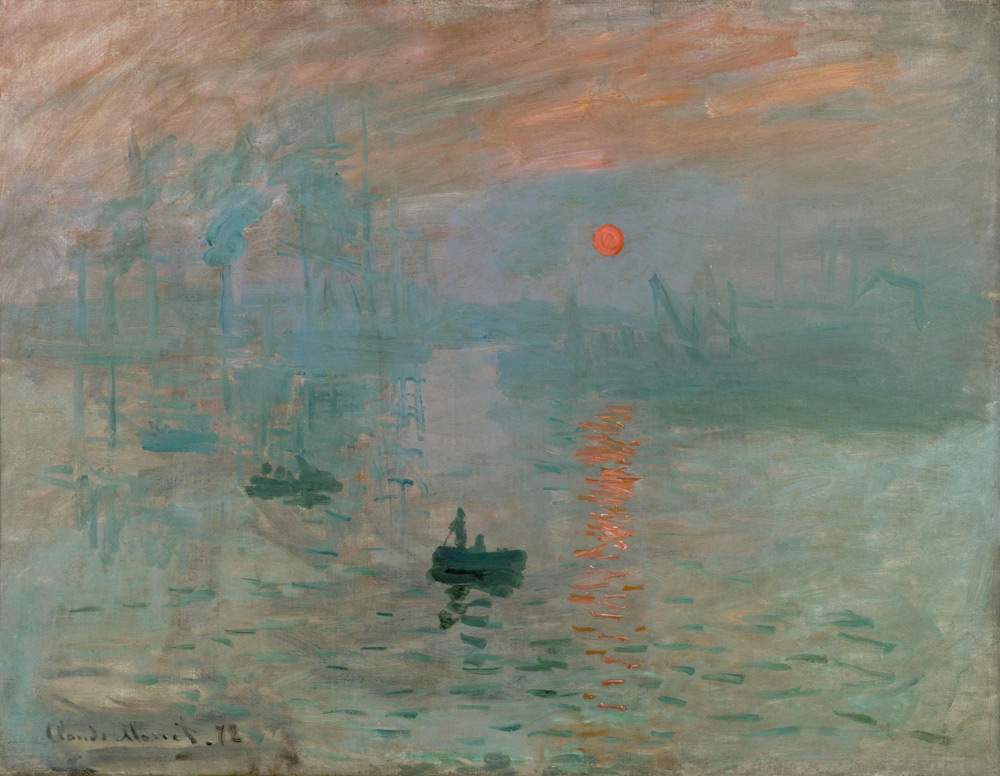

The term “Impressionism” actually comes from one work: it is Impression. Soleil Levant by Claude Monet (Paris, 1840 - Giverny, 1926), to which we have also devoted a lengthy article on these pages. The work was painted by Monet in 1872, and the painter presented it in 1874 at the first exhibition of the Impressionists, which was attended by several other artists who gathered their works in the studio of the Parisian photographer Nadar. However, the exhibition was panned by critic Louis Leroy, who wrote in Le Charivari magazine, “Impression, I was sure of it, There must be some impression in there. And what freedom, what nonchalance in execution! The wallpaper in its embryonic state is even more polished than this painting.” From this negative review came the term “impressionists”: initially used in a derogatory form, it later came to identify that group of artists who had madeimpression, the representation of a precise moment, fleeting and rapid, on canvas one of the keys to their art.

|

| Claude Monet, Impression: soleil levant (1872; oil on canvas, 48 x 63 cm; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

The rise of the Impressionists was by no means a bolt from the blue. Already in France, with the works of the realist painters (such as Gustave Courbet) and with those of the artists of the Barbizon school (such as Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Daubigny), the conditions had been created for a paradigm shift, both in terms of content (no longer just history painting or religious or mythological themes: everyday reality again entered disruptively into the subjects most in vogue among artists), as well as from a formal point of view (the Barbizon painters were the first to “step out” of the atelier and paint en plein air, that is, in the open air). In Italy, too, the conditions had been created for a landscape painting created in the open air and for an art capable of appealing to the artists’ optical interest, that is, the art of the Macchiaioli, who preceded Impressionism by about ten to fifteen years (so much so that one of the greatest Macchiaioli, Giovanni Fattori, in assessing for the first time the works of the Impressionists would affirm the primacy of the Italians, who nevertheless still remained tied to drawing, which the French abandoned instead).

One of the great forerunners of Impressionism was Eugène Boudin (Honfleur, 1824 - Deauville, 1898), who was moreover Monet’s teacher: with his art he gave dignity to “leisure time” by painting views of beaches, snapshots of outings, vacations in nature. The immediacy of Boudin’s painting was one of the starting points of the Impressionists’ researches, both because of the topicality of his thematic choices and because of the way they were approached, with a direct language that faithfully reported on canvas what the artist observed during his outdoor sessions. Boudin did not reach the degree of experimentalism of the Impressionists, which is why he cannot be fully ascribed to their group, but he is nevertheless one of the greatest precursors of the new movement.

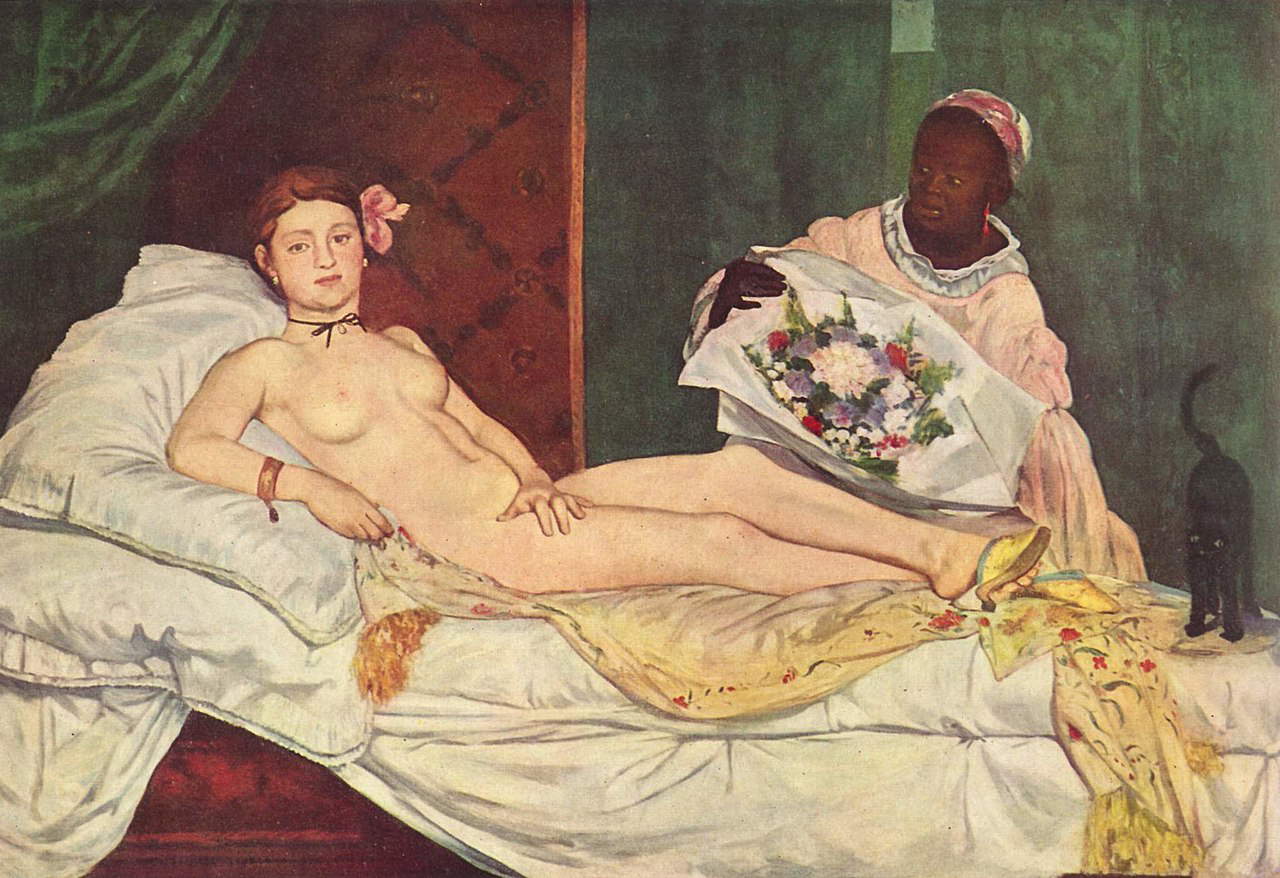

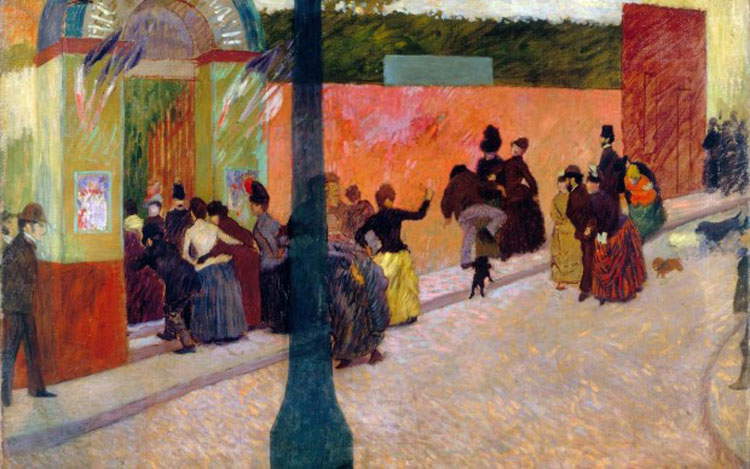

Another artist who anticipated the researches of the Impressionists and then went on to swell their ranks was �?douard Manet (Paris, 1832 1883), who as early as the late 1950s had begun to paint, in a style strongly influenced by realist painting, excerpts from the life of Paris in those years: the nights in the cafés, the spectacles of the theaters, the modernity represented by the passage of the first locomotives and steamboats plying the Seine. Telling modernity in all its aspects: this was also one of the goals of the Impressionists.

|

| Eugène Boudin, The Beach at Trouville (1865; oil on cardboard, 26.5 x 40.5 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

The first exhibition of the Impressionists was held on April 15, 1874 in Nadar’s studio, as anticipated: many artists whose names are not well known to the general public participated, and there was also a great Italian artist, namely Giuseppe De Nittis. Here are the artists who took part in the exhibition: Zacharie Astruc, Antoine-Ferdinand Attendu, �?douard Béliard, Eugène Boudin, Félix Braquemond, �?douard Brandon, Pierre-Isidore Bureau, Adolphe-Félix Cals, Paul Cézanne, Gustave Colin, Louis Debras, Edgar Degas, Jean-Baptiste Armand Guillaumin, Louis La Touche, Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic, Stanislas Lepine, Jean-Baptiste-Léopold Levert, Alfred Meyer, Auguste De Molins, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Mulot-Durivage, Giuseppe De Nittis, Auguste-Louis-Marie Ottin, Léon-Auguste Ottin, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Stanislas-Henri Rouart, Léopold Robert, Alfred Sisley. The most innovative of them all was certainly Claude Monet: his technique of rapid brushstrokes given on the canvas to communicate the impression of the moment was one of the innovations that most attracted critics. Indeed, given the Impressionists’ rejection of academic painting and their desire to deal not with courtly or solemn themes, but with content that was not deemed suitable for “official” painting, one can well understand how conservative critics were anything but on their side.

What were the main innovations of the Impressionists? One of the reasons why the Impressionists are now included in all the “official canons” of art history lies in their approach to reality: the Impressionists, in fact, do not represent reality as all the artists before them had done, trying to return a faithful and almost photographic image of a scene, but simply returning to the eye of the observer what the artist’s eye sees on the canvas. That, then, is why the colors are juxtaposed and not blended, why the figures are blurred, why everything has this air of great immediacy, why the Impressionists’ images are often blurred: because the human eye, in dwelling for a moment on a scene, does not accurately grasp all the elements of what it sees, in the individual details.

“I paint the things I see in the simplest way,” Manet had said. “Thus my Olympia. What could be more spontaneous?” Here is one of the key words of Impressionism: spontaneity. Moreover, for the first time, everyday life of the bourgeoisie systematically entered the artists’ paintings. In their approach to reality, however, the Impressionists marked a difference from the Realists: on their part there was not the desire for social denunciation that had characterized Realist painting. For the Impressionists it was only a matter of showing what the artists saw, and nothing more (although there was no lack of certain paintings later on that can be read as animated by a desire to emphasize certain social issues). Art for art’s sake, in short: the Impressionists asserted that the main purpose of an artist’s activity was his painting or sculpture, and that an artist must be judged solely by what he painted or sculpted.

|

| �?douard Manet, Olympia (1863; oil on canvas, 130.5 x 190 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

As we have seen, there were several artists who participated in the Impressionists’ exhibitions: there were eight in all (1874, 1876, 1877, 1879, 1880, 1881, 1882, 1886). Despite the commonality of purpose and language, the Impressionists matured quite different artistic personalities. Manet, who was eight years older than Monet, never quite severed ties with his academically based substratum: in fact, he had trained in the atelier of Thomas Couture, an artist skilled in history painting. Monet, on the other hand, was the first Impressionist artist tout court: compared to Manet, Monet was more immediate and was much less concerned with compositional aspects, for which Manet, on the other hand, always had a certain attention (given his training, Manet’s constructions were always the most balanced and composed of the Impressionist painters). It could therefore be said that, unlike Monet, Manet operated a kind of combination of new Impressionist language and traditional compositional balance, whereas Monet was decidedly more radical.

Another prominent Impressionist (although he disliked the term “Impressionist”) was Edgar Degas (Paris, 1834 - 1917) who, unlike his colleagues, believed that the artist should not be too passive toward the optical datum, but could allow himself to intervene to “correct” the vision by adding or removing elements deemed essential or, conversely, superfluous to communicate with the viewer. This is seen especially in his paintings depicting dance classes: it was very difficult for Degas to always depict the same environment in the same way. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (Limoges, 1841 Cagnes-sur-Mer, 1919), on the other hand, belongs to the “pleasing” current of Impressionism, so much so that he was probably the most appreciated by the Parisian bourgeoisie of the time and was often called upon to paint family portraits. Like Manet, Renoir was in fact averse to pursuing too radical instances as Monet was doing (so much so that for a time, Renoir even recovered eighteenth-century models), and he almost always subordinated his creations to criteria of balance and agreeableness.

Not dissimilar to Renoir’s approach was that of the most famous female Impressionist, Berthe Morisot (Bourges, 1841 Paris, 1895): for her, too, it was primarily a matter of pleasing Impressionism, which in her case dealt mainly with familiar themes (Morisot was probably the most intimate of the Impressionist painters). At the opposite extreme, in terms of the radical nature of his choices, was one of the most innovative but perhaps also least known Impressionists, Gustave Caillebotte (Paris, 1848 - Gennevilliers, 1894), the youngest of the group but also the most defenseless: he came from a very wealthy family and therefore painted only for pleasure, not for a living, which is why he often abstracted himself from the discussions of his colleagues (although he was a participant in them). Caillebotte proposed an Impressionism made up of bold cuts, snapshots of an almost photographic nature (in some of his paintings he almost seems to make use of a wide-angle lens!), singular views from above(an in-depth discussion can be found at this link). Also little known is the story of the young Frédéric Bazille (Montpellier, 1841 Beaune-la-Rolande, 1870), one of the most innovative artists in France of his time in that he was able to anticipate several innovations of the Impressionists (he was close friends with Monet and had begun to paint along the lines of his older colleague), but who died at only twenty-nine during the Franco-Prussian War: without this tragedy, Bazille would probably be as famous today as Monet.

The two great masters of Impressionist landscape painting, on the other hand, were the Anglo-French Alfred Sisley (Paris, 1839 - Moret-sur-Loing, 1899) and the French-Creole Camille Pissarro (Charlotte Amalie, 1830 - Paris, 1903). Sisley experimented with a language similar to Monet’s but cloaked his visions in melancholy and sentimental notes, which were influenced by his English origins and his study of the masterpieces of Romantics such as Turner and Constable. Moreover, Sisley was also among the least inclined to innovate: once he found his language, he maintained it throughout his career. Pissarro’s views, on the other hand, are more airy, sunny and lively, and in a sense even more original: his way of arranging the masses, with broad brushstrokes that build almost juxtaposed patches of color, anticipates some of the achievements of post-Impressionism. A curiosity: Pissarro was the first Impressionist ever to be known in Italy. It was 1878 when two of his landscapes arrived in Florence, causing moreover skepticism in Italian circles (there were few who understood and appreciated the innovations they introduced: we have also discussed them on these pages).

Italy, too, had its Impressionists: the most innovative was certainly the Apulian Giuseppe De Nittis (Barletta, 1846 - Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 1884), not coincidentally the only Italian to participate in the 1874 exhibition(an in-depth look at his art can be found at this link). He was among the most experimental of the Impressionists: in him can be found both an interest in Japanese art (which not all Impressionists shared, and which would be reworked more later, by Post-Impressionists such as Van Gogh), photographic experiments à la Caillebotte, and a passion for modern life. Other Italian Impressionists include Giovanni Boldini (Ferrara, 1842 - Paris, 1931), one of the greatest interpreters of bourgeois taste, and Federico Zandomeneghi (Venice, 1841 - Paris, 1917), a proponent of a pleasing art that can be placed in the wake of that of Renoir. Finally, as far as Impressionist sculpture is concerned, the principles elaborated in painting were applied in a plastic “version” by Degas and Renoir, but part of the Impressionists’ researches would be grasped in a highly innovative spirit (although he could not be considered an Impressionist for all intents and purposes) by the Italian Medardo Rosso (Turin, 1858 - Milan, 1928), who operated as a “bridge” between Impressionist novelties and the new post-Impressionist instances.

|

| �?douard Manet, The Bar of the Folies-Bergère (1881-1882; oil on canvas, 96 x 130 cm; London, Courtauld Institute of Art) |

|

| Bethe Morisot, Woman and Child on the Balcony (1872, oil on canvas, 60 x 50 cm; private collection) |

|

| Edgar Degas, Little Dancer of Fourteen (1878-81; colored wax, metal, human hair, silk and linen ribbon, lace bodice, cotton and silk tutu, silk slippers, on wooden base, 98.9 x 34.7 x 35.2 cm without base; Washington, National Gallery of Art, Paul Mellon Collection) |

|

| Pierre Auguste Renoir, Woman in an Armchair (1874; oil on canvas, 61 x 50.5 cm; Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts) |

|

| Gustave Caillebotte, Rainy Day in Paris (1877; oil on canvas, 212 cm x 276 cm; Chicago, Art Institute) |

|

| Camille Pissarro, Landscape - The Approaching Storm (1878; oil on canvas; Florence, Galleria dArte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Alfred Sisley, On the Riverbank at Veneux (1881; oil on canvas, 59 x 79 cm; Johannesburg, Johannesburg Art Gallery) |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, The National Gallery and Saint Martin’s Church in London (1877; oil on canvas, 71 x 105.5 cm; Paris, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux Arts de la Ville de Paris) |

|

| Giovanni Boldini, Gertrude Elizabeth (née Blood), Lady Colin Campbell (1894; oil on canvas; London, National Portrait Gallery) |

|

| Federico Zandomeneghi, Au Théâtre (ca. 1895; oil on canvas, 71 x 88 cm; Piceni Foundation Collection) |

Already with the last exhibition, that of 1886, new realities appeared in the limelight of French and European art, and the fact that the very young Georges Seurat, among others, exhibited at that year’s show indicated that Impressionism had already found its heir: the innovations introduced by the Impressionists, especially those concerning their interest in optical phenomena, would later be fully embraced by the Pointillist painters. We then find the legacy of the Impressionists in the works of all the greatest of the turn of the century, from Van Gogh to Gauguin to Matisse and Cézanne. Experiences that were born on the path traced by the Impressionists.

Of course, many of the Impressionists continued to work for a long time, for example, Boldini even continued until after World War I to produce works that did not deviate from his style of the 1880s: but art by then was set on totally new paths.

When their works are not around for exhibitions, it is possible to see the masterpieces of Impressionism in a number of museums that we can consider somewhat like their “temples”: so we can start in Paris with the Musée d’Orsay where there is perhaps the world’s most important collection of Impressionist art. Also in the French capital, a visit to the Musée Marmottan, which holds Impression. Soleil levant by Monet and some works from his Water Lilies cycle. The “triptych” of museums dedicated to Impressionism concludes with the Musée de l’Orangerie, where there is another copious collection of works by the movement’s main artists. Still in France, wishing to continue the tour outside Paris, one can mark the Musée d’Art Moderne in Le Havre, the Musée des Impressionnismes in Giverny (where Monet’s very famous garden is located), and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Caen: all sites located in Normandy, a land of great importance for Impressionism because it was here that Monet experimented with his first innovations under Boudin’s guidance, and he returned several times during his career.

In Italy, on the other hand, there are not very many museums that house works by the Impressionists: to see them and get to know them in depth one must wait for one of the many exhibitions that are organized in our country, but in their absence one can still make up for it. Manet’s only painting in Italy is at the GAM in Milan (it is Portrait of Mr. Arnaud on Horseback), while for Monet we move to the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica e Contemporanea in Rome, which houses one of Monet’s Water Lilies. At the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Florence’s Palazzo Pitti, on the other hand, are Pissarro’s landscapes, which arrived in the city in 1878: these are the first Impressionist works to arrive in Italy. Much easier to find works by the Italian Impressionists, on the other hand: in this case, you can mark on your agenda a visit to the Boldini Museum in Ferrara.

|

| Impressionists: who were they and what did the main artists of impressionism do |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.