Otto Dix (Gera, 1891 - Singe, 1969) was a leading painter of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), an artistic avant-garde that emerged in the early postwar period in Germany and lasted until the Weimar Republic years with the advent of Nazism. The influences of the movement were many: the Neue Sachlichkeit artists were mainly inspired by neoclassicism, realism,expressionism, surrealism and Dadaism. Painting, within the group, was divided into two major categories: on the one hand there was a realist branch, in which the subjects of the works were represented from a critical and objective point of view, while in contrast there was a current more related to classicism, where the subjects of the works were often landscapes, portraits, and still lifes. Otto dix took part in the realist current, focusing his paintings on harsh and crude themes.

Because of his often war-related themes, with the advent of Nazism Otto Dix was considered a “degenerate” painter. His works were considered offensive to soldiers and the state. During his rise, the Nazi regime confiscated numerous works considered offensive toward Germany and the new regime, taking them from national museums. After the seizure of some 5,238 works in just two weeks, an exhibition of degenerate art was organized in 1937 at the Institute of Archaeology in the Hofgarten (Munich) with the aim of highlighting the decadence and insanity of the painters on display by denigrating and mocking them(read more about so-called degenerate art under the Nazi regime here).

The exhibition hosted about 650 works by painters such as: Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso, Piet Mondrian, Vasilij Kandinsky, Marc Chagall and Otto Dix himself. It was curated down to the smallest detail and the works were arranged in different rooms in a specific order, works offensive to religion,, works painted by Jewish artists, works depicting women, soldiers or peasants painted in a manner disrespectful according to the regime’s criteria (Otto Dix’s works were also included in the latter category). At the end of the exhibition, most of the paintings were burned while the remainder were sold for pennies.

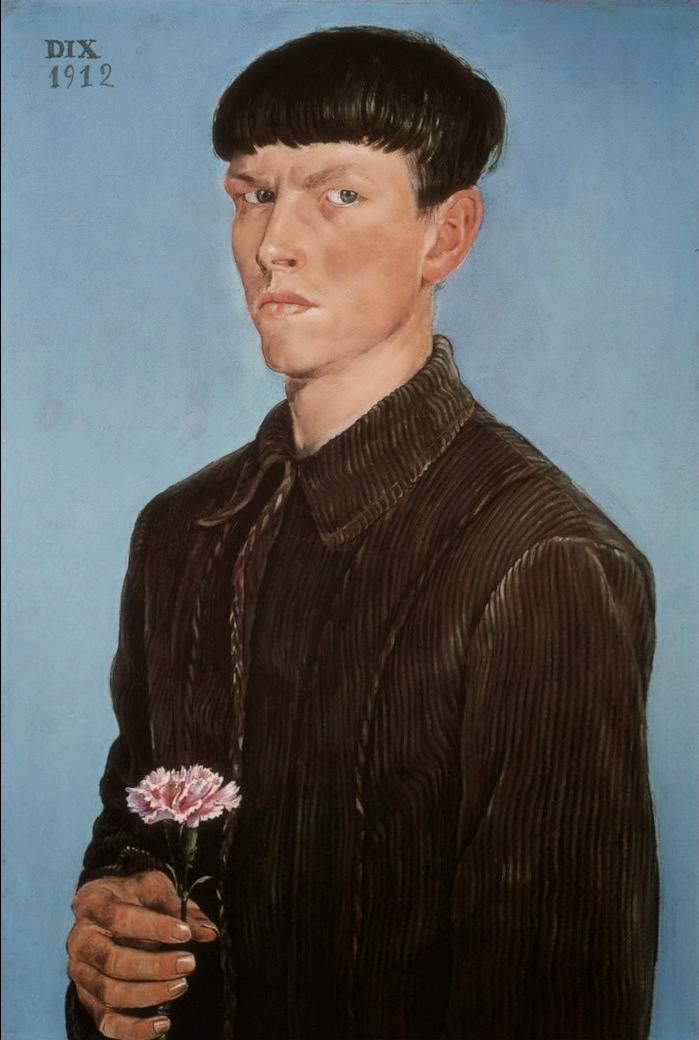

|

| Otto Dix, Self-Portrait with Carnation (1912; oil on paper mounted on panel, 73.7 x 49.5 cm; Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts) |

Otto Dix was born on December 2, 1891, in Gera, Thuringia, to a family of humble origins. At the age of nineteen he joined the Dresden School of Decorative Arts and soon after, in 1909, enrolled in theAcademy of Fine Arts (HfBK) where he specialized in portrait painting. His curiosity soon led him to visit numerous exhibitions, in particular, in 1912 he had the opportunity to attend a Vincent van Gogh exhibition and was positively impressed. With the outbreak of World War I, he decided to enlist as a volunteer in the German army fighting in Russia, Poland, France and the Flanders campaigns. Despite his initial enthusiasm he returned from the war very tried and traumatized. He strongly expressed the pain he experienced in the war in his drawings, and it was during this period that he executed sketches pertaining to the wartime world, producing works such as Invalids of War Play Cards (1920) and the series consisting of fifty etchings The War (1924).

Returning home in 1919 he joined the expressionist movement called the New Dresden Secession(Dresdner Sezession) and became an assistant at the Akademie Der Bildenden Künste in Dresden. Together with George Grosz, Rudolf Schlichter and John Heartfield he founded the German Dadaist group, organizing the first international Dadaist fair in Berlin in 1920. In 1922 he settled in Dusseldorf where he approached a style of painting related to realism; from this time on, the subjects of his paintings took on a high symbolic value. The following year, in 1923, he married Martha Koch, then wife of Hans Koch, a doctor and art collector. These years were the most prolific of the painter’s life; in 1923 he painted The Trench (1920-23), one of his most significant works, which emphasized his raw and violent style. The painting, after it was purchased and exhibited in the Cologne Museum, was returned to him following negative and impressed comments from critics and the public. In 1925 in Mannheim he participated in the exhibition of the new movement, and in 1927 he was instead hired to teach at the Dresden Academy. During his time at theUniversity of Dresden he painted one of his most famous works, The Great City (1927-1928), also known as Metropolis, a triptych where he denounced through deliberately heightened contrast the moral degradation of society in those years.

In 1931 he was elected a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts. Shortly afterwards, in 1933, Hitler seized power and Otto Dix’s works were removed from museums: his art from this time onwards for the Nazis was considered “degenerate,” he was ordered to stop exhibiting, and his works were seized and burned. As a result, he was also dismissed from all his public positions such as that at the University of Dresden. Initially, he continued to paint and portray social themes with a strong critical value such as criticism of the National Socialist regime while concealing and masking it by the use of symbols and allegories typical of Christianity. It was during this period that he painted the Triumph of Death (1934). Shortly after the Nazis seized power, the artist moved to Lake Constance where he returned to express himself in a classical style by creating landscape themes or portraits, thus abandoning social themes by drawing on Renaissance artists. In 1945 he was captured by the Nazis who accused him of participating in the assassination attempt on Hitler, and he was released the following year. With the fall of the Nazi regime he resumed war-related themes in which he was particularly successful, being appointed a member of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin in 1955. That same year he participated in the first edition of Documenta in Kassel. He died on July 25, 1969, in Singen, Germany.

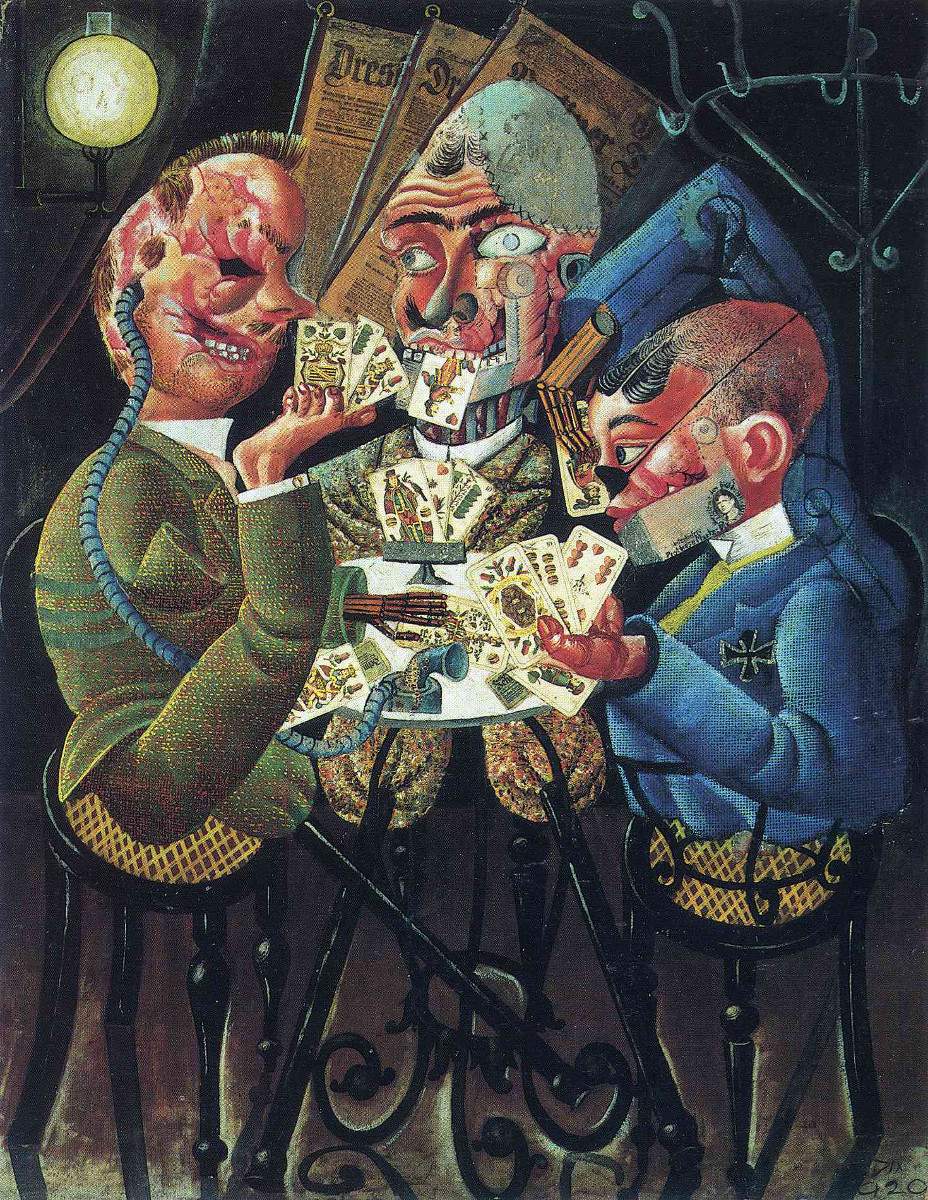

|

| Otto Dix, War Invalids Play Cards (1920; oil and collage on canvas, 110 x 87 cm; Berlin, Neue Nationalgalerie) |

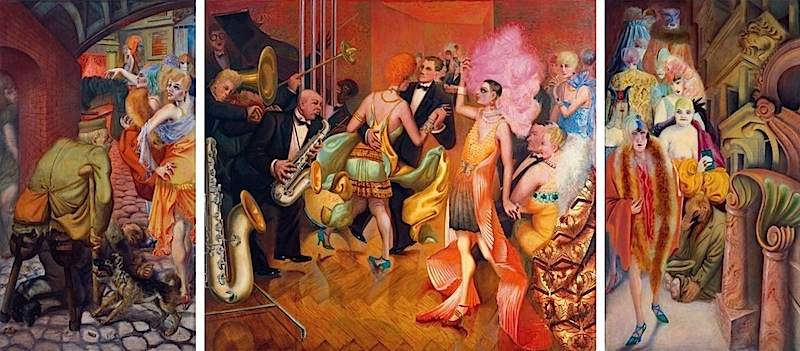

|

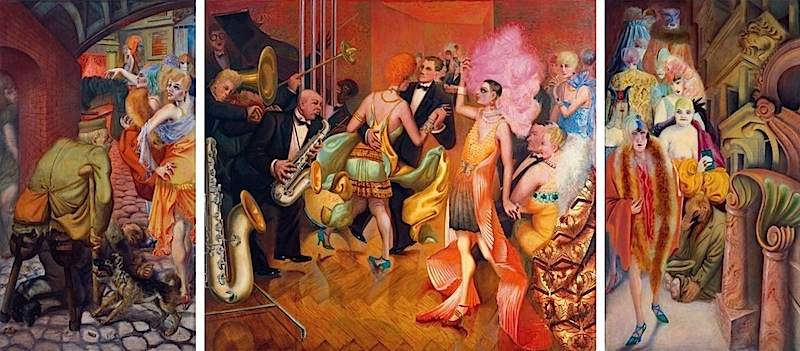

| Otto Dix, Triptych of the Metropolis (1927-1928; mixed media on panel, 181 x 402 cm; Stuttgart, Kunstmuseum) |

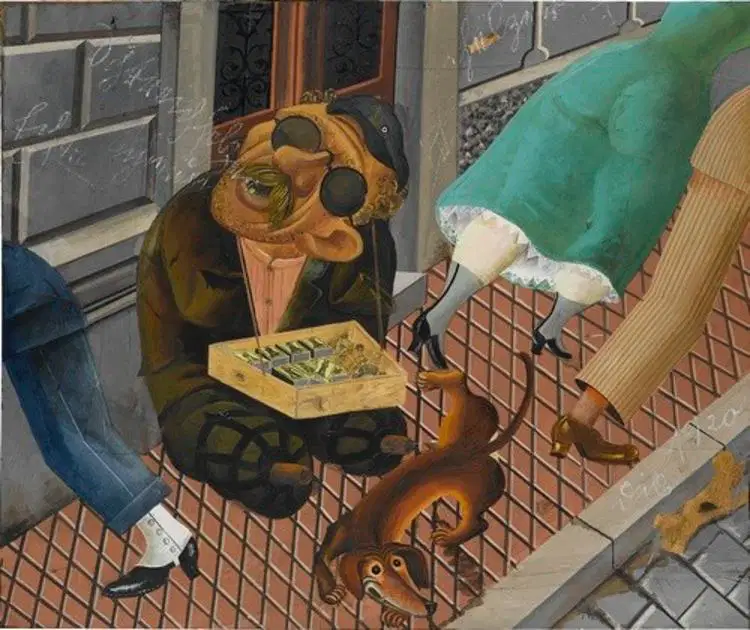

Best known for certain themes he dealt with in his art, considered scandalous by some, such as prostitution or the violence of war, Otto Dix was one of the most influential painters of the German New Objectivity. In all his paintings he always depicted the hard truth by taking an objective and realist gaze. His paintings thus became testimonies of pain and objectivity. In addition to his denunciation of the horrors of the war he also shone through his denunciation of German society, which experienced the war passively, in contrast to him, who was greatly traumatized. In this postwar period he painted a number of works such as The Match Seller (1921) where he depicted an old gentleman sitting on a sidewalk in the city of Dresden while the people around him, depicted in typical bourgeois attire, walk past him avoiding him and disregarding him. The emphasis of his social denunciation also emerges from the painting Invalids of War Playing Cards (1920) where he depicted three amputee men enthusiastic and amused at while playing cards in front of a card table. Mutilated people represented in Otto Dix’s art the symbol of the cruelty of war-they were the most recurrent subjects of all his painting in those years. More amputees, in fact, were depicted in the painting Via Praga (1921) where a former soldier without limbs, resembling a mannequin because of his two wooden legs and left arm, is kept away from passers-by.

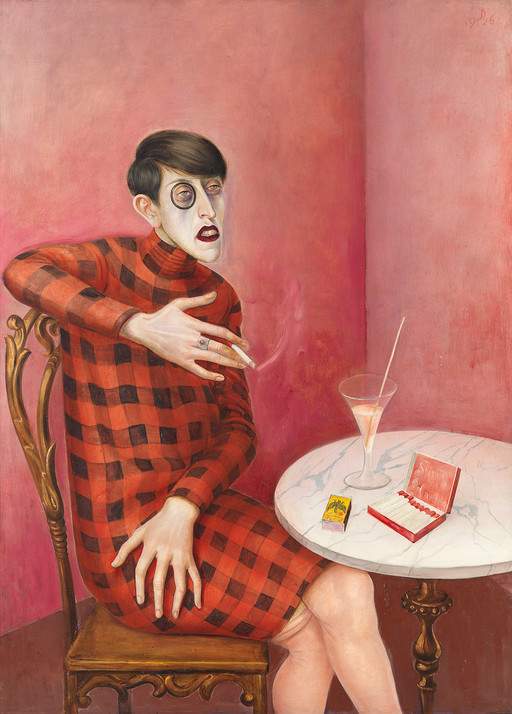

From his return from Berlin in 1927 and with his subsequent move to Dresden for work, Otto Dix’s painting abandoned the theme of war, dwelling instead on subjects more related to social classes; he thus began here to produce portraits of the German bourgeoisie. During these years he painted The Portrait of Sylvia Von Harden, one of the best known paintings of his artistic career. The woman portrayed, Sylvia Von Harden, was a young poetess representative of a new idea of the bourgeoisie and untethered from any stereotype of beauty, thus becoming the perfect muse for the painter. Otto Dix portrayed the woman as he saw her: short legs, pointed nose, large hands, and with a blank, stern gaze. The scene takes place around a table at Café Romain, among the painter’s favorite and most frequented places. The predominant color, pink, represents the color of the walls, the color of the matches, and the color of the woman’s dress.

In the Triptych of the Metropolis (1927-28), as was his wont, Otto Dix implemented a harsh critique of Berlin customs of the Weimar Republic period. The painting is a triptych where a certain inspiration and reference to themedieval art world can be seen. He divided the three panels as follows: in the center he placed the largest one where he depicted the interior of a club where people are dancing and enjoying themselves in eccentric fancy clothes; in the left panel he depicted a poor and sad scenario where prostitutes and two men appear, one of whom is an amputee and one a drunkard lying on the ground; finally, in the third and last panel, the one on the right, he depicted a series of women in fancy evening gowns passing by an amputee always without paying attention to them. In all panels the main subjects are predominantly female figures who in each section of the painting give us information about the different social statuses represented in the triptych. Social status reaches its highest degree in the central panel where pageantry and luxury are present. The right panel represents a lower-middle class while the left panel portrays a very low social status.

The formal setting of the altarpiece was also taken up in the War Triptych (1928) where Otto Dix provocatively depicted war scenes instead of religious figures. Besides causing many deaths, the war also brought with it the moral decay of society: misery became something ordinary and normal. In this altarpiece, the artist painted and exalted all the devastation that war can cause, thus depicting a series of figures of bombed and dismembered bodies in a swampy and deserted landscape. The soldier in the center panel and the various soldiers in the left panel were depicted as the only survivors in a scene of death and violence.

With the rise to power of Nazism, Otto Dix abandoned crude and violent representation and turned to an inner exile that brought his painting to a radical change. Among his last provocative paintings were The Seven Deadly Sins (1933), a painting he made after being forced to leave teaching at the Dresden Academy of Art, charged with intense symbolism. In the foreground the painter depicts a witch (avarice) while carrying envy who seems to resemble Hitler, behind her is a skeleton holding a scythe symbolically representing sloth, behind her stands a woman with bare breasts representing lust, followed by there is gluttony given by a man represented with his face inside a pot, next to him is pride given by a figure putting back excrement, and to his right is wrath symbolized by an animal figure full of hatred.

In the last period of his life, Otto Dix was inspired mainly by classical and Renaissance painters, demonstrating that artistic innovation lies not in the creation of a new style of painting but mostly in the depiction of new themes and subjects. In 1927 he wrote, “One watchword has inspired a whole generation of artists in recent years: ’Create new forms of expression.’ I doubt whether this is possible. And if you stop before the paintings of the old masters or sink into the study of new creations you will certainly agree with me. Novelty in painting, in my opinion, consists in broadening the choice of subjects, developing the expressive forms already adopted by the old masters.”

Although many works were lost or burned during the Nazi period as many can be seen at numerous world institutions. German museums preserve a number of Otto Dix’s works: his masterpieces can be seen at the Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the Galerie Neue Meister in Dresden, the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, the Kunsthalle in Karlsruhe, and the Museum Folkwang in Essen. In Gera it is also possible to visit the Otto-Dix-Haus, the house where the artist spent the first years of his life, which has now become a museum. In Italy, the GAM - Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Turin opes the painting (Der) Matrose Fritz Müller aus Pieschen (1919). Other paintings, mainly portraits, are exhibited in major museums around the world such as: the MoMA in New York, the Detroit Institute of Arts (where the very famous Self-Portrait with Carnation is located the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

|

| Otto Dix, The Match Seller (1920; oil and collage on canvas, 141.5 x 166 cm; Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie) |

|

| Otto Dix, Portrait of Sylvia von Harden (1926; oil and tempera on panel, 121 x 89 cm; Paris, Centre Pompidou) |

|

| Otto Dix, War Triptych (1929-1932; oil on canvas, central panel 204 x 204 cm, side panels 204 x 102 cm; Dresden, Galerie Neue Meister) |

|

| Otto Dix, The Seven Deadly Sins (1933; oil on canvas; Karlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle) |

|

| Otto Dix. The life and works of the master of the Neue Sachlichkeit |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.