In the collective imagination, Jan Vermeer is considered a solitary genius. In reality, he may have had a workshop and collaborators who had to help him realize his works. This is the conclusion reached by the National Gallery in Washington on the basis of research carried out on the occasion of the exhibition Vermeer’s Secrets, scheduled to run from Oct. 8, 2022 to Jan. 8, 2023, and for which important new scientific findings had already been anticipated by the multidisciplinary research team consisting of Marjorie E. Wieseman, Alexandra Libby, Dina Anchin, Melanie Gifford, Lisha Deming Glinsman, Kathryn A. Dooley and John K. Delaney.

The museum called the discoveries around Johannes Vermeer (Delft, 1632 - 1675) "groundbreaking," beginning with the confirmation that Girl with a Flute, a much-debated painting, was actually done by a Vermeer collaborator, not the Dutch artist himself, as previously believed. The idea that Vermeer worked together with collaborators, according to the research team, challenges the long-standing belief that he was a solitary artist-Vermeer would, on the contrary, have been a master or mentor to younger artists. Since Vermeer’s known oeuvre numbers only about 35 accepted paintings, scholars have generally considered it unlikely that he had students or assistants. And with no surviving documents providing evidence of a workshop (no register of pupils recorded by the Delft painters’ guild, no mention of assistants in the notes of visitors to Vermeer’s studio), it was believed that he worked alone.

That is, until now. “The existence of other artists working with Johannes Vermeer,” says Kaywin Feldman, director of the National Gallery of Art, “is perhaps one of the most significant new discoveries about the artist in recent decades. It fundamentally changes our understanding of Vermeer. I am incredibly proud of the interdisciplinary team of National Gallery staff who worked together to study these paintings, building on decades of research and using advanced scientific technology to arrive at exciting discoveries that add new information to what we know about the enigmatic artist.”

The National Gallery team concluded that Girl with a Flute (c. 1669-1675) is not, in fact, by Johannes Vermeer. Instead, scholars believe the painting was made by a Vermeer collaborator, someone who understood the Dutch artist’s process and materials but was unable to fully master them. Exactly who that person might be remains to be determined, but the implication that Vermeer worked closely with other artists is significant, as it revises the long-standing belief that Vermeer worked in isolation. The artist at the time unknown could have been a student or apprentice, an amateur who paid Vermeer for lessons, a painter hired on a project-by-project basis, or even a member of Vermeer’s family.

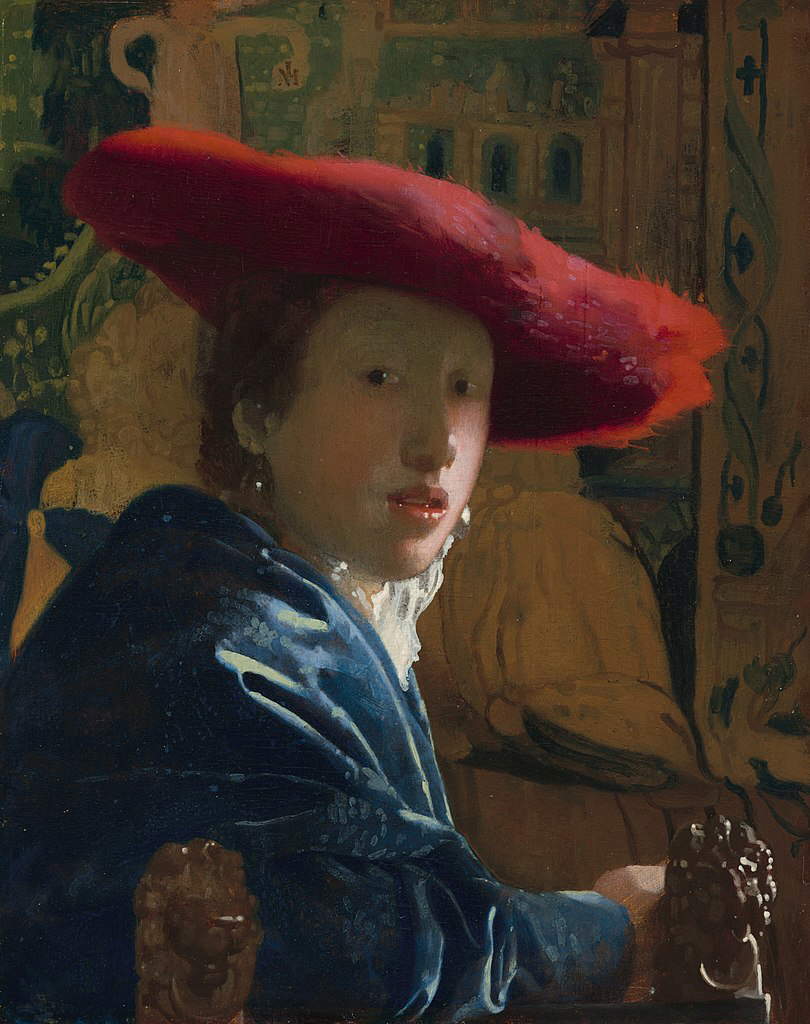

The team compared Girl with a Flute to Vermeer’s Girl with a Red Hat: both are small paintings that were previously assumed to be a pair because of similarities in subject matter, size and use of a wood panel support, which was unusual for Vermeer. However, the application of paint in the Girl with a Flute is very different from that in the Girl with a Red Hat. Not only does it lack the precision for which Vermeer is known, but the artist seems to have lacked Vermeer’s control: the brushwork appears clumsy and the pigments used in the final painting are coarsely ground, giving the surface an almost grainy character. Vermeer, on the other hand, coarsely ground his pigments for the ground paint and more finely for the final paint layers in order to achieve their delicate surfaces. The artist of the Girl with the Flute inexplicably reversed this order. Despite the different handling, microscopic analysis of the pigments showed that both compositions used the same pigments, including even the green earth shadows of the face, a typical feature of Vermeer’s paintings. Taken together, these results according to the research team would clearly show that although Vermeer did not paint the Girl with the Flute, this artist was intimately familiar with Vermeer’s unique working methods.

The research also led the curators to determine that Vermeer’s The Girl with the Red Hat was made at a turning point in the artist’s career. The painting shows Vermeer experimenting with new techniques (bright colors, a bolder way of applying paint) that foreshadow paintings produced in the final phase of his career. Consequently, they believe the painting should be dated slightly later, to about 1669 (the work was previously dated to about 1666-1667). Marjorie E. Wieseman, curator and head of the National Gallery’s Northern European painting department; Alexandra Libby, associate curator of the Northern European painting department; E. Melanie Gifford, conservator and researcher of painting technology; and Dina Anchin, associate conservator of painting, pointed to the painting as an experiment by the artist: the moment when he began to paint his final image with a schematic rendering of forms and exaggerated contrasts of light and shadow, features that he had previously limited to the background paint.

Many of the findings, according to the museum, broaden our understanding of the early stages of Vermeer’s painting process. One of the most exciting discoveries, made by comparing the results of various scientific imaging techniques with microscopic analysis, was the realization that Vermeer began his paintings with broad strokes in a rapidly applied ground varnish that established a solid foundation for his smooth, refined surface painting. Indeed, microscopic examinations of the final paint layers show that Vermeer used relatively fluid paints to create his typical smooth surfaces. Together, microscopic analysis of the paint samples and pigment maps obtained by spectroscopy show how the artist combined pigments to create his extraordinary surface effects.

Building on half a century of previous technical studies of Vermeer’s works at the National Gallery, researchers took advantage of Covid-related closures in 2020/2021 to examine the museum’s four paintings by and attributed to Johannes Vermeer, which are rarely removed from their walls, especially at the same time. Vermeer’s Secret thus aims to offer the public a behind-the-scenes look at how the National Gallery’s curators, conservators, and scientists studied the museum’s four precious paintings, as well as two 20th-century forgeries, to understand “what makes a Vermeer a Vermeer.” The exhibition thus showcases some of the most interesting discoveries along with scientific images of the paintings and even one of the specialized technical instruments used to conduct the imaging.

|

| Did Vermeer have a workshop? Washington announces groundbreaking discoveries about the artist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.