In Pompeii, in the Roman villa of Civita Giuliana (about 600 meters outside the city walls), the furnishings of a room assigned to slaves have been reconstructed. The furnishings were reconstructed using the technique of casts, which exists only in and around Pompeii: materials such as furniture and textiles, as well as bodies of victims of the 79 A.D. eruption, were covered by the pyroclastic cloud, which then became solid soil while decomposed organic matter left a void in the ground: an imprint that, when filled with plaster, revealed its original form. Using this method, it was therefore possible to reconstruct the furnishings of the room in question. The method of obtaining plaster casts from decomposed organic objects that leave a void in the ash was first systematically applied by Giuseppe Fiorelli in 1863, although earlier attempts are attested, and casts of furniture are among the earliest examples

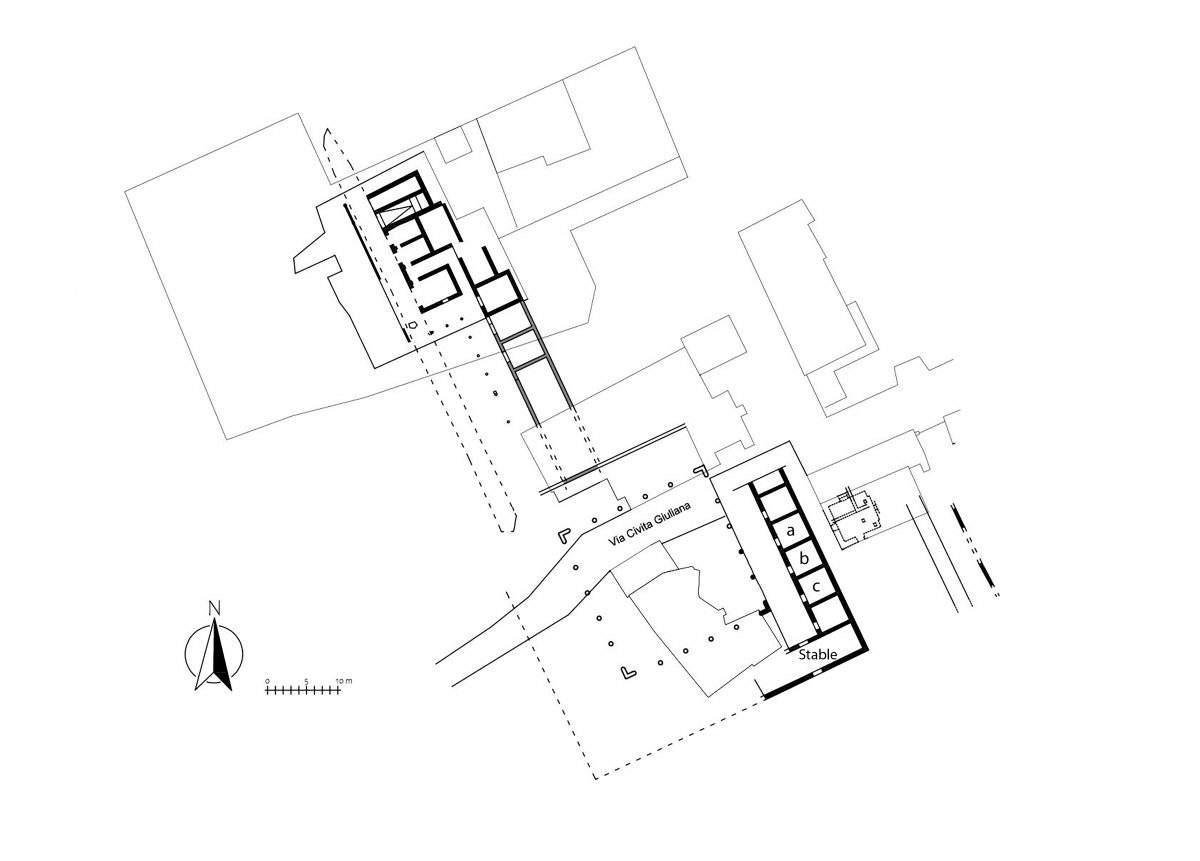

The new room, named “room ”A,“ is not an entirely new discovery, since a similar room had already been found, although this new room looks different from the one already known as room ”C," reconstructed in November 2021, in which three cots were placed and which served at the same time as a storage room. What has emerged now suggests a definite hierarchy within the servants’ quarters. Indeed, the slave rooms excavated from 2021 have provided a unique insight into the living conditions of people who ended up in slavery in ancient times. As a result, we glimpse a “virtually photographic” quality (so the director of Pompeii Archaeological Park, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, in the scientific article published in the Park’se-journal ) of the lives of a group of people who rarely appear in written sources, and if they do, it is almost exclusively from an elite perspective.

Pompeii, the slave room known as

Pompeii, the slave room known as Pompeii, the slave room known as

Pompeii, the slave room known as Pompeii, the slave room known as

Pompeii, the slave room known asRoom “c” was excavated in autumn 2021 and became known as the “slave room” of Civita Giuliana. Like the other servant rooms unearthed so far, it measured about 16 square meters. “Entering from the portico surrounding the courtyard, where the chariot had been parked,” Zuchtriegel continues, "a visitor would have been looking at the back wall of the building, from where a single window, rather small and at the top of the wall, illuminated the room. The opus reticulatum walls, dating to the end of the first century B.C., were not plastered, except for a white stain below the window. In the center, a nail had been driven into the wall. The oil lamp that hung from it was found broken on the floor below. The function of this piece of plaster must therefore have been to reflect and amplify the poor light from the lamp.“ Since room ”c" was filled to the height of about 1 m from the floor level with the pyroclastic layer that had enveloped everything like a warm cloud of ash and then solidified, thus preserving the imprints of organic materials long since decomposed, much of the wooden furniture and textiles could be reconstructed, as mentioned above, as plaster casts.

Even in the case of the new room “A,” no traces of plaster were found to cover the opus reticulatum walls: as has long been observed, servants’ quarters in Pompeii are often recognizable by the absence of wall decorations. And even inside room “A” bedding was found. The broad weave of the bed’s rope net is perfectly observable from the plaster cast as is the blanket left untidy on the bed. As with the other beds of this type, there does not appear to have been a mattress on this bed. The remains (charred wood) of a large L-shaped shelf were discovered above the bed on the west wall. A large wicker basket found in the center of the room in the cinerite must have once been on the shelf, but it was thrown off by the pyroclastic wave. Inside it were two smaller baskets, all preserved as plaster casts. On the shelf surrounding the room, cups, plates and various other pieces of tableware were found.

Along the north wall, a bed of a different type came to light. It is known as a “back bed” and is a more comfortable bedding than the grabatus, from the Greek κράββατος, a much less comfortable bed without a mattress. An ancient term for the backboard bed was lectus cubicularis, because it was used for resting in the cubiculum (bedroom), as opposed to the lectus trilinaris on which guests reclined during meals and feasts. At least two of the wooden sides characteristic of this type of bed can be identified by the stain left on the ash by the red-painted outlines of the rectangles that once decorated the panelling. The bed was severely damaged by the tunnels dug into the ancient villa by grave robbers. However, the dimensions can be reconstructed accurately: the mattress was about 0.30 m from the floor level, while the panels reached a height of at least 0.95 m from the floor level. The bed was about 1.80 m long and 1 m wide. In the northeast corner of the room is a vertical Dressel 25-type amphora wedged between the wall and the bed. Along the east wall under the window, which is 2.20 m above floor level, are two small cupboards next to each other. The northernmost one measures 0.83 m high, 0.95 m long, 0.56 m deep. It contained some metal objects including a knife blade and a small scythe currently being analyzed and preserved. The smaller cabinet is 1.10 m high, 0.68 m long and 0.33 m deep. Both cabinets, although damaged by looting burrows, show that they were made of long, narrow wooden planks as shown by the plaster cast. In front of them is a very simple bench with four legs, about 0.36 m high, 1.60 m long and 0.24 m wide. In the southeast corner are two Dressel 2-4 amphorae, one of which was found capped with a pebble. A pile of wooden stakes is leaning against the wall; next to them, another amphora, upside down, is waiting to be fully excavated. In front of the amphorae in the southeast corner are the various plaster casts of wooden elements that are not immediately recognizable and perhaps fell from the shelf above. Among these can be recognized a rectangular iron blade of a hoe.

Pompeii, the slave room known as

Pompeii, the slave room known as Pompeii, the slave room known as

Pompeii, the slave room known as Pompeii, the slave room known as room

Pompeii, the slave room known as roomWhat do these well-preserved rooms tell us about slave quarters that the available written and archaeological evidence on the material life of Roman slaves has not yet revealed? “We will only be able to fully answer this question after the excavation is completed,” Zuchtriegel says. "However, we can already draw some preliminary conclusions from the data that have emerged so far. On the one hand, the slave quarters of the Civita Giuliana villa do not give the impression of a prison building that prevented the escape of slaves. As far as we know, no iron grating blocked the windows, which were certainly small. Neither the doors of the individual rooms nor the passage leading from the stable to the outside of the complex appear to have been locked with locks: no traces to this effect have been found. At the same time, the small lock of the box found in the center of room ’C’ is perfectly recognizable, thus suggesting that the iron locks of the doors, if present, would have been preserved. This, on the other hand, could help explain the situation within the villa complex. Since there appear to be no insurmountable physical barriers to prevent the escape of the slave laborers who lived in the villa, other control mechanisms must have existed. Having the slaves live and sleep in groups of two or three in one room could perhaps have suited this purpose. Indeed, the community of slaves not only fostered the creation of friendships and families (although slaves could not formally marry), but also allowed for the establishment of forms of mutual control. The lectus cubicularis in room ’A’ may have belonged to a servant in a somewhat elevated position, perhaps a kind of overseer. Such slaves were often granted privileges in order to make them reliable allies of the master, for example by allowing them to live with a slave in a de facto marriage. The promise of manumission, which became quite common in the early imperial period, also helped to spur slaves, especially older slaves, to side with the master in the task of overseeing the slave community rather than with runaway slaves or even to take the risk of escaping themselves, especially with uncertain prospects, as survival outside the sphere of the villa could prove even more atrocious and harsh punishments for escapes. In addition to reflecting possible kinship ties among slaves, double and triple rooms could conform to the need to establish constant mutual control among enslaved workers, even at night. Allowing foremen and other slaves to form families is in fact presented by Varro(De re rustica, 1.17.5) not only as a means of rewarding them and increasing the labor force (children born to enslaved women were automatically slaves themselves), but also explicitly as a way to make them “more attached to wealth” . Thus, to get the whole picture, we should add an atmosphere of suspicion to the image of simplicity and intimacy offered by the rooms of the villa’s slave quarters. There was certainly solidarity, perhaps even friendship and love (bonds that often lasted after the slave was freed), but there must also have been fear and terror of being accused before the master by a fellow slave. Observing the rodent-infested rooms of Civita Giuliana, we are invited to appreciate how, despite everything, the people living there struggled to maintain a minimum of dignity and comfort. But we must not forget the silence and isolation into which the bonds of slavery drove these people, perhaps even more so since these bonds were not physical (given the lack of grated windows, door locks and so on) but invisible and thus potentially undermining any authentic form of communication."

The micro-excavation of pots and amphorae from room “C” has meanwhile revealed the presence of at least three rodents: two mice in an amphora and a rat in a jug, placed under one of the beds and from which the animal apparently tried to escape when it died in the pyroclastic flow of the eruption. Details that once again underscore the precarious and unhygienic conditions in which the last of the society of the time lived.

Pompeii, the slave room

Pompeii, the slave room Pompeii, the slave room known as

Pompeii, the slave room known as Pompeii, the slave room known as room

Pompeii, the slave room known as roomThe archaeological exploration of the villa of Civita Giuliana, which had already been excavated in 1907-’08, began in 2017 based on a collaboration between the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, as the body responsible for the protection of thearea surrounding the ancient city, and the Torre Annunziata Public Prosecutor’s Office, which together with the Carabinieri had uncovered a longstanding clandestine excavation activity in the area of the Villa, which was later broken up and prosecuted both criminally and civilly.

The Villa of Civita Giuliana, located about 600 meters north of ancient Pompeii, was discovered and partially excavated in the years 1907-1908. In 2017, the Pompeii Archaeological Park began cooperating with the local Public Prosecutor’s Office, which was investigating illegal excavations in the area. As it turned out, the owners of a house located on the site of the ancient villa had dug an underground network of tunnels to systematically loot the site and deprive it of frescoes and precious artifacts destined to be smuggled abroad and sold on the antiques market. The archaeological excavation of the villa, begun under the direction of then-director Massimo Osanna, is still ongoing and has led to a number of unexpected discoveries. These include a stable where it was possible to make a plaster cast of a horse, the remains of a ceremonial chariot (pilentum) decorated with silver and bronze medallions and sconces, and two victims of the Vesuvius eruption.

“What has been reconstructed confirms the need to continue scientific research in a place that, thanks to the work of the judiciary and the Carabinieri, has been wrested from looting and illicit trafficking of archaeological goods to tell remarkable moments of daily life in antiquity. What is being learned about the material conditions and social organization of the period opens new horizons for historical and archaeological studies. Pompeii represents a unicum that the whole world envies us. With Operation Greater Pompeii concluded, we plan new initiatives and new funding to continue research and protection,” says Culture Minister Gennaro Sangiuliano.

“We are committed to continuing the research and planning the fruition of a place that, like no other in the ancient world tells the story of the everyday life of the last,” says Director Zuchtriegel. “On the occasion of the reopening of the Antiquarium of Boscoreale next fall, we plan a room to inform the public about the ongoing excavations, the same ones that, under the direction of my predecessor, Massimo Osanna, led to the discovery of the ceremonial chariot recently on display in Rome, at the Baths of Diocletian. I would like to thank, in addition to the team engaged in the archaeological excavation, the Prosecutor’s Office led by Nunzio Fragliasso for their excellent work.”

For the Director General of Museums, Massimo Osanna: “The research in Civita Giuliana is a virtuous example of protection and enhancement of our heritage. A firm collaboration between the Ministry of Culture, the Torre Annunziata Public Prosecutor’s Office and law enforcement agencies have already made it possible to bring to light an impressive complex and its extraordinary furnishings, including the Bride’s Chariot. The new acquisitions confirm the relevance of the project. These activities will lead, I hope soon, to return to the Pompeian community and to the public at large, an archaeological area of great importance that tells another piece of the biography of people, of different social classes, who lived 2000 years ago.”

|

| Major discovery in Pompeii: slave room found |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.