A new page opens in the history of Australianrock art with the identification of a novel figurative style, called Linear Naturalistic Figures (LNF), documented at 22 sites in the northeastern Kimberley area of Western Australia. The discovery, published in the scientific journal Australian Archaeology, is the result of six years of field research as part of the Kimberley Visions project, has uncovered nearly one hundred rock images depicting exclusively animals, delineated by a continuous, linear line, often devoid of internal fill and any anthropomorphic elements. The discovery thus marks a breakthrough in our understanding of the stylistic sequences and social and environmental dynamics that swept through the area during the Middle and Late Holocene. Nonindigenous research on Kimberley rock art has ancient roots. The earliest known documentation dates back to 1838, by explorer George Grey. This was followed during the 19th and 20th centuries by the observations of clergy members and ethnographers who, together with anthropologists and archaeologists, began to record the rich stylistic diversity of the area. One of the first systematic proposals for classification was due to Leslie Maynard, who in 1977 suggested a tripartite scheme: Panaramite engravings, simple figures (Simple Figurative) and complex figures (Complex Figurative), including the Kimberley paintings. In later years, interest in the antiquity of graphic expressions led to the definition of two important relative stylistic sequences, elaborated by Grahame Walsh in 1994 and David Welch in 1990. Both are based on criteria such as overlapping paintings, degree of erosion, use of color, and other iconographic attributes.

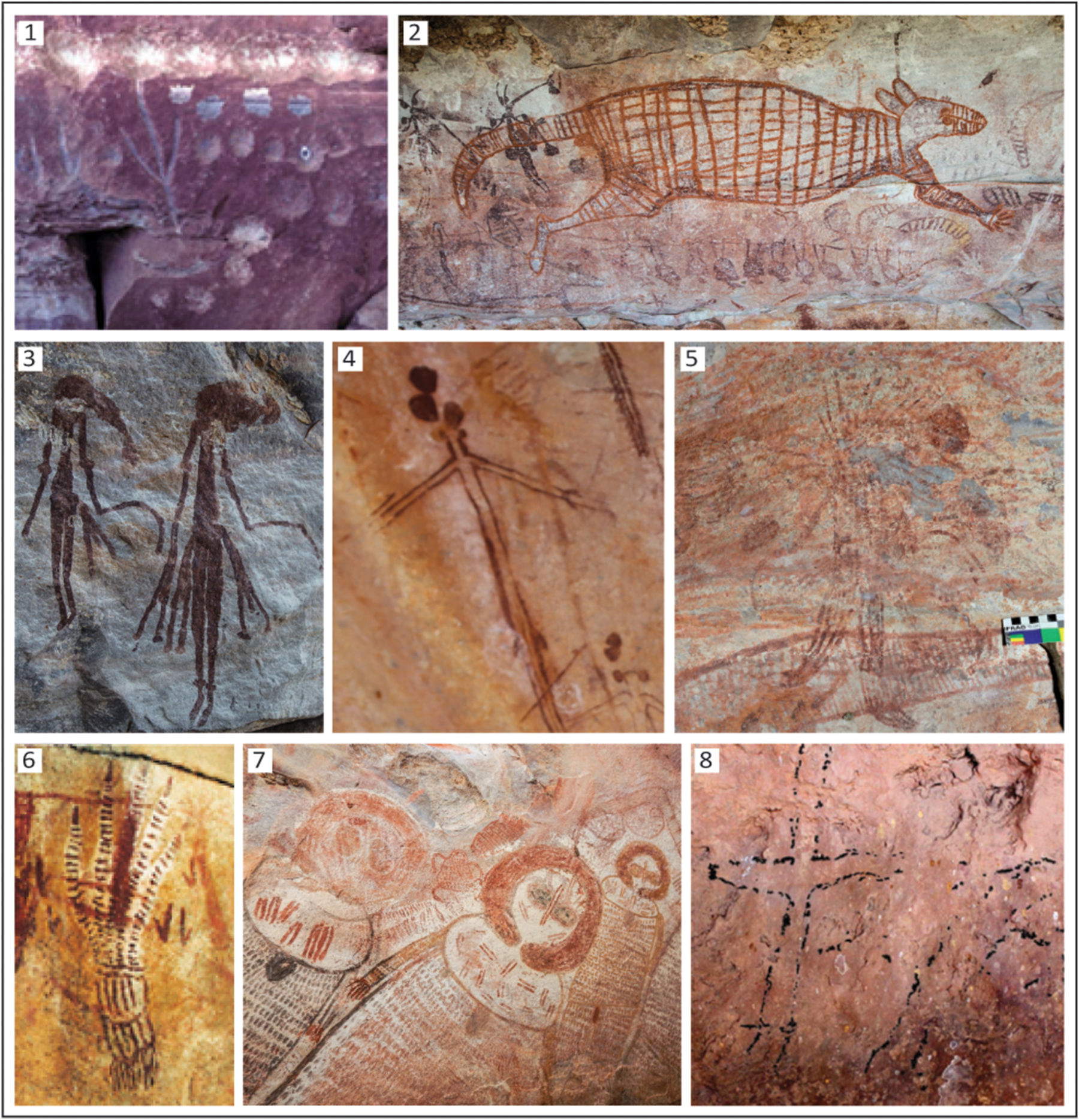

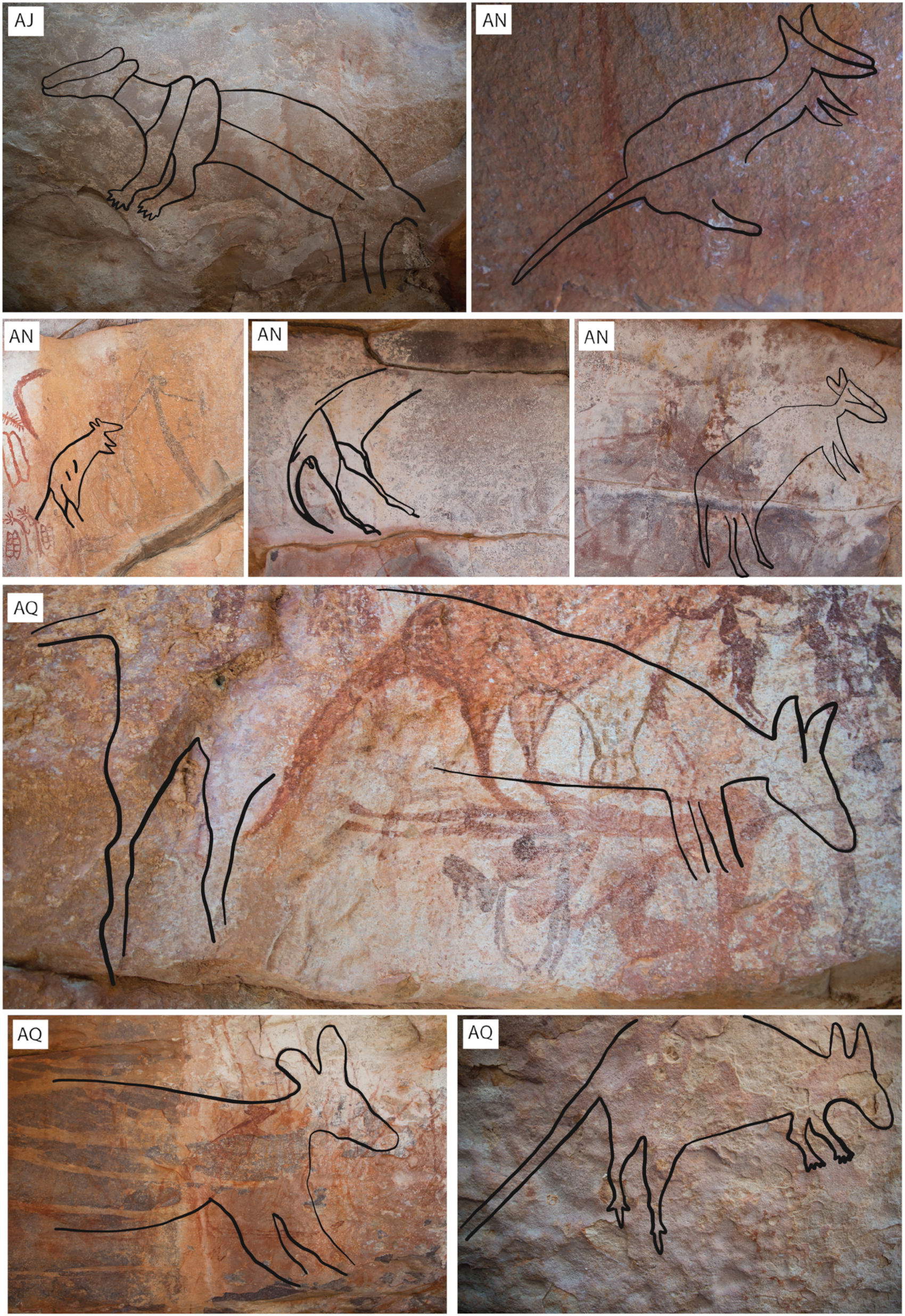

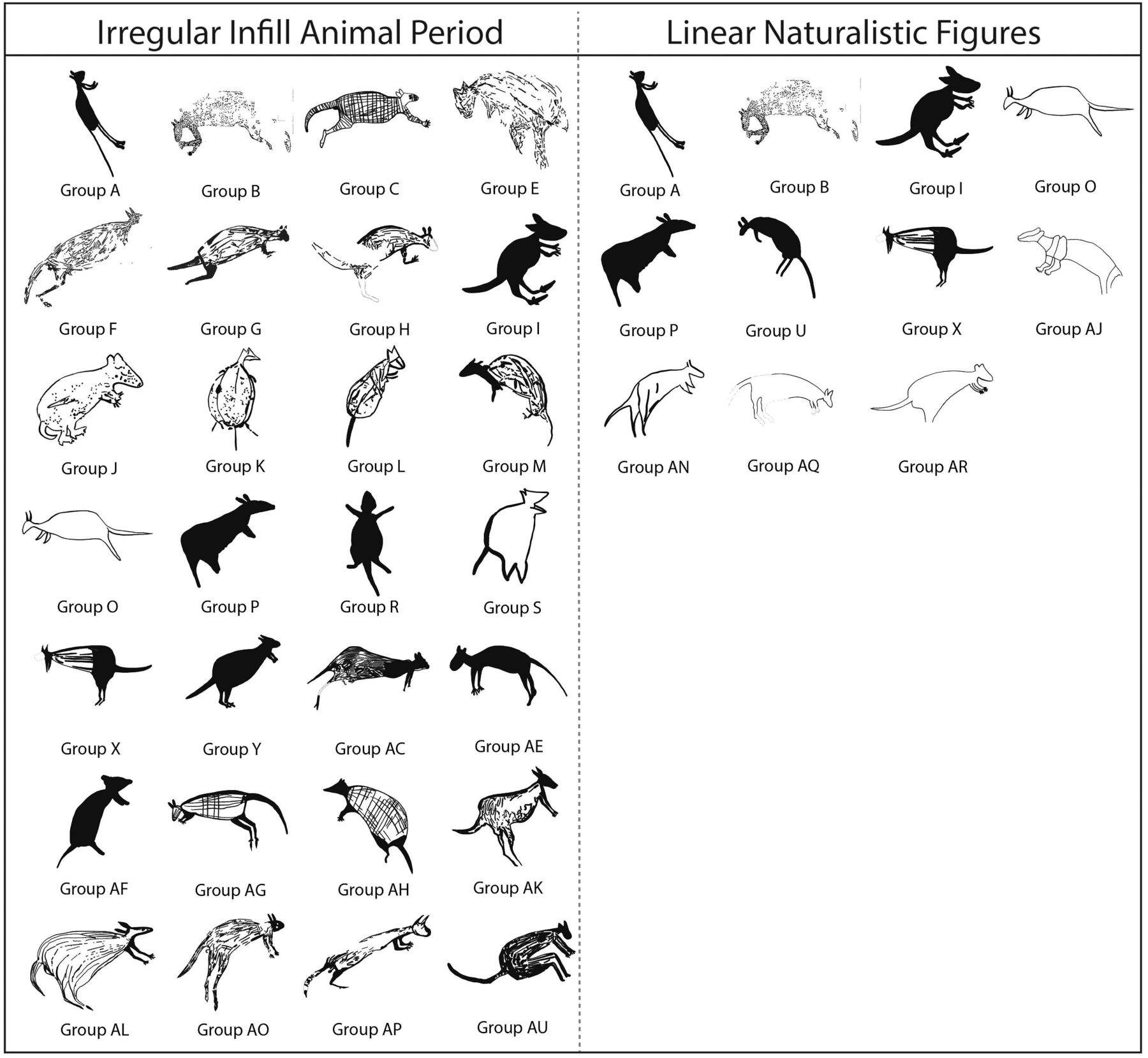

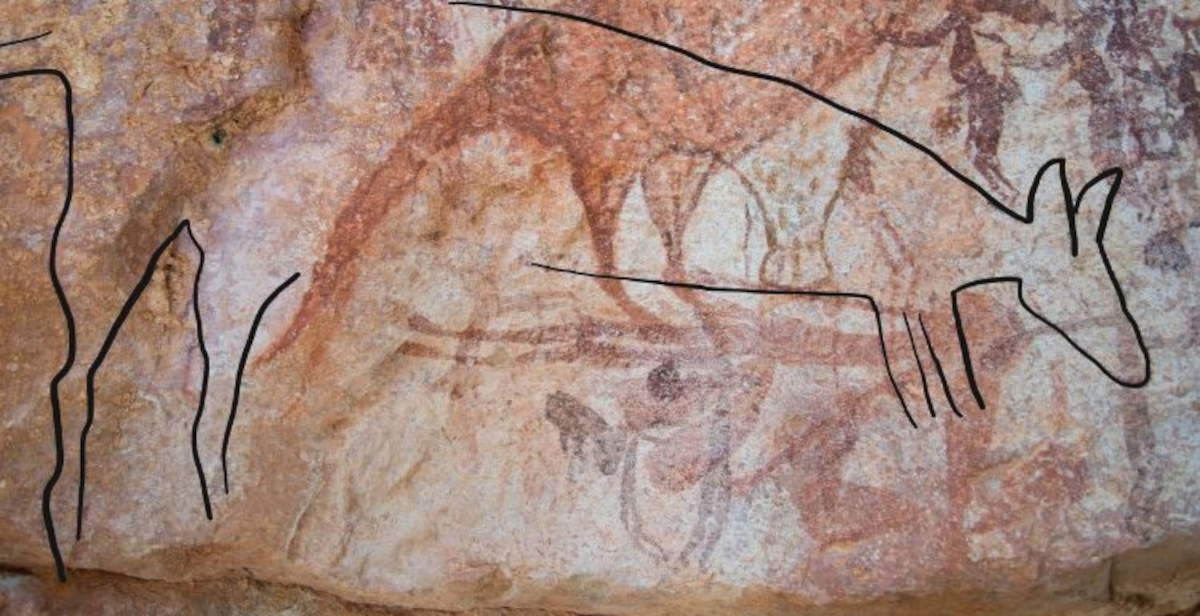

The new style, developed by researchers Ana Paula Motta, Sven Ouzman, Peter Veth, and the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation, is distinguished by a number of formal features: animals depicted in profile or distorted perspectives, devoid of complex decoration, with a sharp, uniform outline. The figures, sometimes up to two meters long, are concentrated in the basins of the Drysdale and King George rivers, on vertical walls of easily visible rock shelters. Scholars point out that the absence of human representations and the prevalence of naturalistic fauna make the style profoundly distinct from earlier and later styles. Comparison with the Irregular Infill Animal Period (IIAP) style, which dates to the terminal Pleistocene and is also characterized by faunal subjects, showed that LNFs exhibit more simplified rendering, reduced chromatic use (monochrome red or orange tones) and less variety of body postures. Macropods, kangaroos, wallabies and related species, dominate the scene, and are often rendered in static positions, with essential features and realistic proportions. Morphological analysis identified eleven body types, five of which appear unique to LNFs and not found in IIAP motifs.

The overlap sequences, a key element in establishing the relative chronology of the paintings, showed that the LNF figures always sit above the Gwion (also known as Bradshaw), Static Polychrome, and IIAP motifs, but below the Wanjina figures, which are attributed to more recent eras and are still active in Aboriginal ritual practices. The intermediate position of the LNFs suggests a date to the Middle and Late Holocene, during a period of major environmental transformations: the stabilization of sea levels, the introduction of the dingo, and the increase in linguistic diversity are some of the factors that would have contributed to redefining the symbolic relationships between community, territory, and fauna.

The centrality of the animal subject in this style, after centuries of anthropomorphic prevalence in the Gwion and Static Polychrome, is interpreted by researchers as a conceptual return to the animal figure as a means of identity and relational expression. According to scholars, LNFs may reflect a renewed attachment to the totem system, in which humans and nonhumans share common origins and spiritual ties. While in the past the IIAP style had often functioned as a vague container for all naturalistic representations with partial infill, today, thanks to the identification of the distinctive features of LNFs, it is possible to recognize an autonomous, coherent and replicable phase. The selective use of lines, the voluntary limitation of infill, and the disappearance of anthropomorphic elements thus signal a definite aesthetic and symbolic intention that cannot be traced back to incomplete variants of pre-existing styles.

In parallel, comparisons with rock art from Arnhem Land and eastern Indonesia, where figurative motifs have been dated up to 51,000 years ago, have shown that although formal similarities exist, each cultural context develops its own codes. Scholars warn that without clear and repeatable stylistic criteria, the risk of misleading projections or overgeneralizations remains high. In this sense, LNFs present a useful example for understanding how seemingly similar styles can actually respond to radically different social and ritual needs. The new style adds to an already articulated sequence of at least eight macro-styles documented in the Kimberley: from the earliest cupules to Gwion figures to post-colonial contact art. The LNF fits into this landscape as an autonomous phase, located between the richly decorated anthropomorphic representations and the spiritual iconography of the Wanjina. Its emergence confirms the hypothesis that Aboriginal graphic systems respond to a recursive and situated dynamic evolution in which tradition and innovation coexist in balance. According to the authors, LNF paintings can be interpreted as a form of communication aimed at strengthening social ties, transmitting ecological knowledge and reaffirming belonging to an ever-changing territory. In this key, rock art would be an active device for renegotiating the present.

|

| New Aboriginal rock style discovered in Kimberley, Western Australia |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.