During an archaeological surveillance operation related to road works in the historic center of the French city of Toul, in the department of Meurthe-et-Moselle, archaeologists from theInstitut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives (INRAP) unearthed an important find. These are the fragments of an equestrian statue from the Renaissance period, which remained buried for centuries near the city’s northern gate, known in medieval documents as “Portae platae,” or “The Square.”

The site has been under excavation since March 2024, in conjunction with an urban redevelopment program. At the end of the work, scheduled for May 2025, it was possible to identify the central portion of the structure of the medieval north gate, demolished shortly after 1700 as part of the urban transformations desired by Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban. The modern fortification work had involved the removal of the ancient gate, the base of which had been filled with rubble and architectural remnants of freestone, dating from the 15th century.

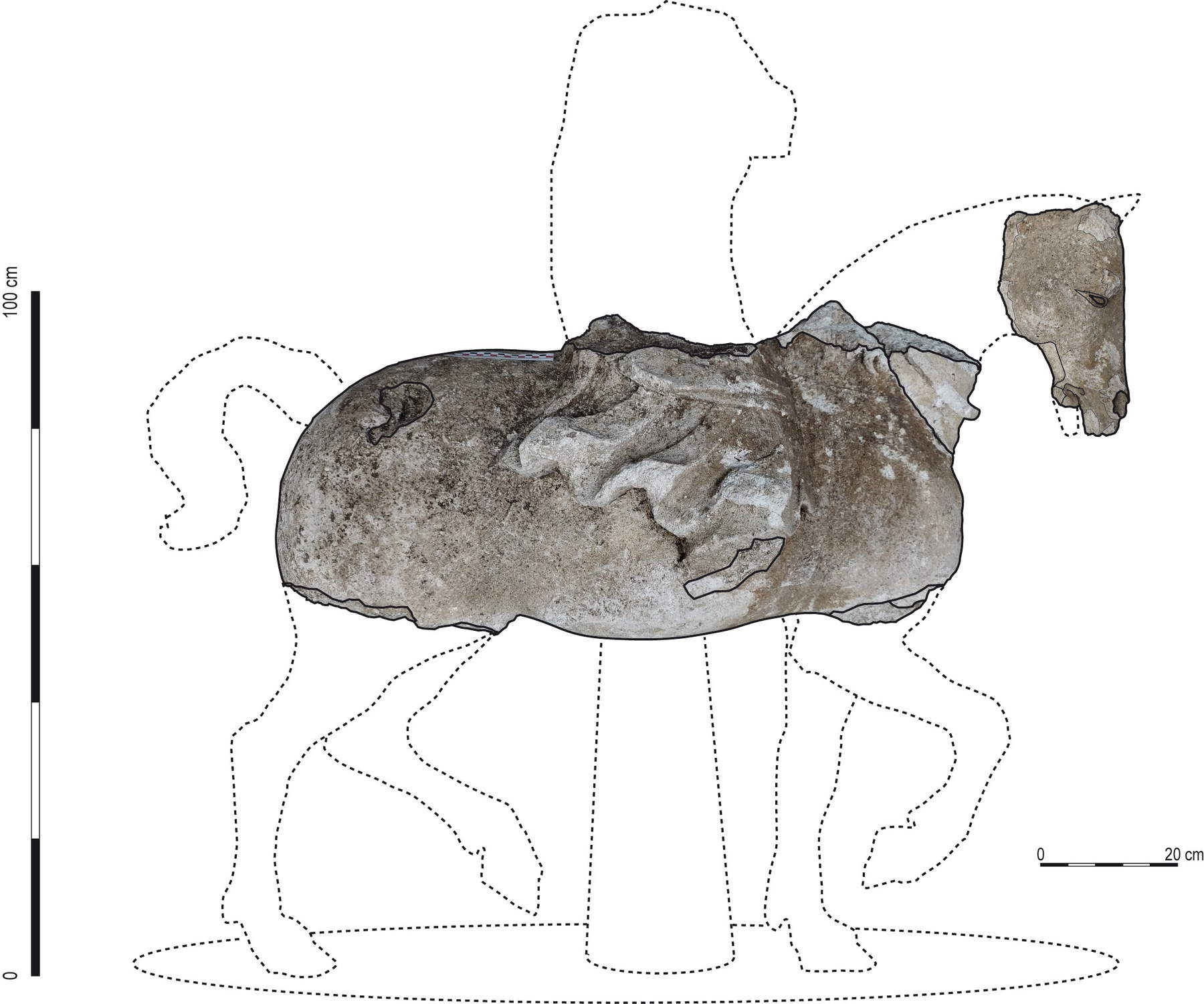

At the road leading to the gate, on the inner side of the walls, a pit more than a meter deep, filled with earth and debris, was found. Inside, archaeologists recovered fragments of a sculpture in the round, depicting a horseman on horseback. The work, broken into numerous parts, has been attributed to the Renaissance period because of its style and rendering of details. The horse appears to be largely preserved, with the body almost intact, including the front legs, neck, and head. Of the rider, however, the pelvis, upper thighs and torso remain, lying on a clearly visible under saddle. The head and most of the upper limbs are missing, elements that limit the possibility of certain identification of the figure depicted. The main fragment, which includes the rider’s torso and the horse’s body, measures more than 1.10 meters in both length and height, with a width varying between 50 and 60 centimeters and weighing more than 500 kilograms. Archaeologists estimate that the original group must have reached about 1.60 meters in height and length. The material used was a white shell limestone, presumably from the Barrois (or Perthois) region, known for its quarries.

The location of the find suggests that the statue was originally placed in a niche above the portico of the city gate in its 15th-16th century configuration. During the demolition of the structure in the early 18th century, the sculptural group may have been knocked down and dropped at the foot of the monument, only to be quickly buried, perhaps to hide it or to eliminate its visual memory. The gesture appears intentional, suggesting a specific desire to erase symbols no longer consistent with the new strategic function of the fortifications.

The iconography of the group harks back to models from classical antiquity: the knight is depicted as a noble personage, dressed in a tunic and wrapped in a cloak, or chlamys, according to a type of portraiture already adopted in Roman statuary. Consistent comparisons can be found in several Italian cities of the 15th century, Naples, Florence, and Milan, where Renaissance artists ideally reinterpreted heroic and imperial figures inspired by ancient examples. Among the most obvious references are the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius on the Capitoline Hill in Rome and that of Regisole, placed in Padua before its destruction.

Numerous Italian artists, attracted to France during the 16th century at the invitation of aristocratic and religious patrons, contributed to the introduction of these models into Lorraine monumental sculpture. The choice to depict a noble figure in classical dress, rather than a sovereign or a condottiere in armor, as would occur later between the 16th and 18th centuries, actually reveals a preference for an aesthetic that looks directly to antiquity, rather than to the medieval tradition of the armed knight.

In the absence of written documents or representational sources relating to the decoration of Toul’s north gate, the attribution of the work remains open. In any case, archaeologists advance two main hypotheses about the possible patron. One traces the statue back to French King Henry II, who in 1552 conquered the Three Lorraine Bishoprics, including Toul, and initiated a program of strengthening urban defenses. The other, considered more plausible, is related to Cardinal John III of Lorraine, bishop of Toul, Metz and Verdun in the first half of the 16th century. A central figure in the political and artistic scene of the time, the prelate was a fervent supporter of the Renaissance and maintained diplomatic relations with the papacy on behalf of King Francis I. It would not be surprising, then, that such a statue was commissioned by him or his entourage to grace the northern entrance to the Episcopal city.

Today, INRAP has begun a complex task of reassembling the 27 recovered fragments. In parallel, in-depth stylistic analysis and 3D photogrammetry scanning are being carried out to facilitate the study of the work and its possible museographic restitution.

|

| Renaissance equestrian statue found in Toul, France, buried after demolition of north gate |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.