by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 08/02/2018

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition Voglia d'Italia. International Collecting in the Rome of the Vittoriano, in Rome, Palazzo Venezia and Vittoriano, through April 8, 2018.

To tell the story of the origins, the development and the entry into the public patrimony of a collection that two American spouses assembled between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, in the context of a newly-born Italy, capable of attracting, with its treasures, the interest of legions of foreign collectors, and which at the time knew the first measures in terms of conservation, protection and export of works of art: this, in broad terms, is the theme of the exhibition Voglia d’Italia. International Collecting in the Rome of the Vittoriano, which takes its starting point from the in-depth study of an impressive and eclectic collection, that of George Washington Wurts (Trenton, 1843 - Rome, 1928) and Henrietta Tower (Pottsville, 1856 - Lucerne, 1933), and then ranges over the international collecting that characterized Italy in those years: the period considered in the review curated by Emanuele Pellegrini is roughly that covering the fifty-year period from the breach of Porta Pia, with the consequent annexation of Rome to the Kingdom of Italy, to the advent of the fascist regime. In between, many different stories, but all intertwined, starting with that of a Rome that, proclaimed capital of Italy by law in 1871, was involved in a mammoth renovation effort and saw the opening of dozens of construction sites that would unearth an endless number of ancient artifacts. Among the construction sites that opened was that of the Vittoriano, home of the exhibition along with Palazzo Venezia, the building to which the Wurts-Tower collection was transferred en bloc in 1933, following the death of Henrietta Tower, according to the explicit intention of the couple, who in their testamentary legacy had expressed their wish to donate it to the Italian state.

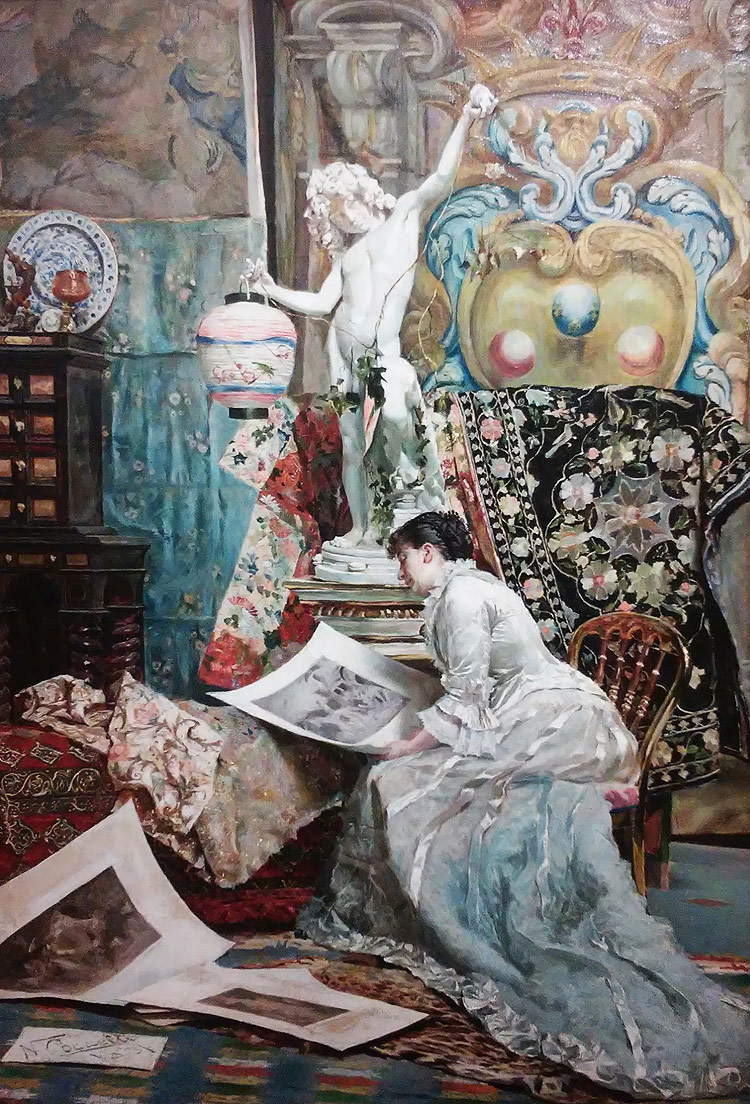

And then there are the individual stories of the collectors, who collected works of art according to their own taste and inclinations: there were the fine connoisseurs who collected by being guided by their artistic interests (this was the case with Herbert Percy Horne and Bernard Berenson), there were those who collected with the specific intention of setting up a collection that, through outstanding examples and according to a plan that included very specific nuclei, could give an account of the artistic productions of various parts of the world (Frederick Stibbert), those who nurtured a predilection for a circumscribed period of art history and regulated their purchases accordingly (Robert J. Nevin), and also those who had no specific purpose, but bought objects as a souvenir of a trip or stay, or because they were driven by the desire to possess an object that represented something on an emotional level (the latter is the case with the Wurts-Tower collection, which, although it could be subdivided into a few main thematic nuclei, never had an organic character). And again, as anticipated, there is the history of the birth of protection, but also that of the art trade, that of the origins of “made in Italy,” that of the production of fakes. Varied were the types of objects towards which the interest of collectors was directed: not only paintings and sculptures, but also fine textiles (tapestries, carpets), ceramics and porcelain, exotic artifacts from all corners of the world, prints and drawings, furniture and pottery. All summed up in a tasty painting by Napoleone Coccetti (Florence, 1850 - ?), kept in a private collection and on display in the rooms at the Vittoriano, which depicts a high-ranking lady grappling with the examination of some prints, in a setting that presents almost all the types of art objects that aroused the curiosity of collectors at the time.

It is difficult to suggest to the visitor where to begin his or her itinerary, whether from Palazzo Venezia, the place that houses the section devoted to the focus on the Wurts-Tower collection, or from the Vittoriano, where the section on the historical and cultural context is instead set up. Here, in order to better present to the reader the general framework within which the Wurts’ story unfolded, it was deemed safer to start from the section that occupies the spaces of the Sacconi Galleries at the Vittoriano.

|

| The entrance to the exhibition Voglia d’Italia at the Vittoriano |

|

| A room of the exhibition Voglia d’Italia |

|

| George Washington Wurts and Henrietta Tower |

|

| A room of the Wurts-Tower in a period photograph |

|

| Napoleon Coccetti, Au salon (1881; oil on canvas; Florence, private collection) |

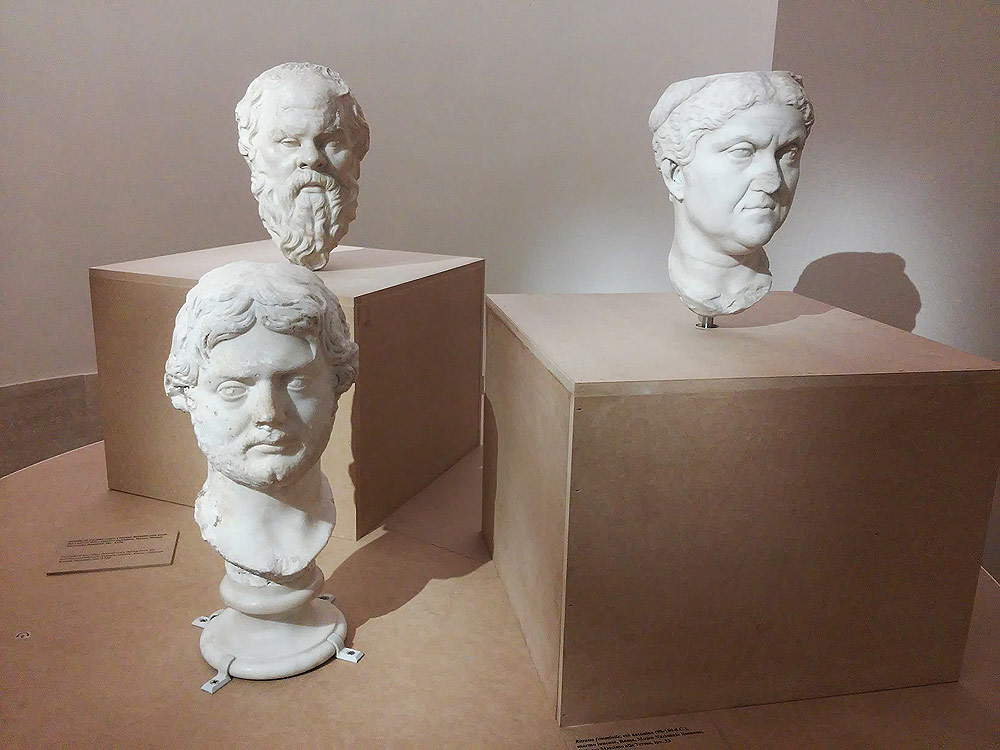

The beginning of the itinerary is entrusted to three Roman heads, all found underground in Rome between 1886 and 1888, a couple during excavation work for the monument to Victor Emmanuel II (the Female Portrait of the Antonine Age and the Portrait of Socrates), while the third, a Male Portrait from the mid-third century AD, was found by a private citizen who sold it to an antiquarian, and following two other passages the work ended up at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. A different fate befell the other two portraits, which were immediately housed in the Museo Nazionale Romano di Palazzo Massimo alle Terme: since they were discovered during a public construction site, it was easy for the Italian state to proceed with their conservation at the museum. The case of the other portrait is different: it is true that the archaeologist who sold it to the U.S. museum, Rodolfo Lanciani (Rome, 1845 - 1929), as a result of some risky transactions (including the sale of the aforementioned portrait) was accused of illicit trafficking in antiquities and, although without suffering official sanctions, considered it prudent to leave any institutional archaeological assignment, but it should also be noted that a more iron discipline on export would come only in 1903, with the law “On the export abroad of ancient excavated objects and other objects of supreme historical and artistic value,” which prohibited the export outside the national borders of any artistic object included in the catalog of goods of supreme value, established as a result of the Nasi law, passed the previous year, and which represented the Italian state’s first intervention in the field of protection.

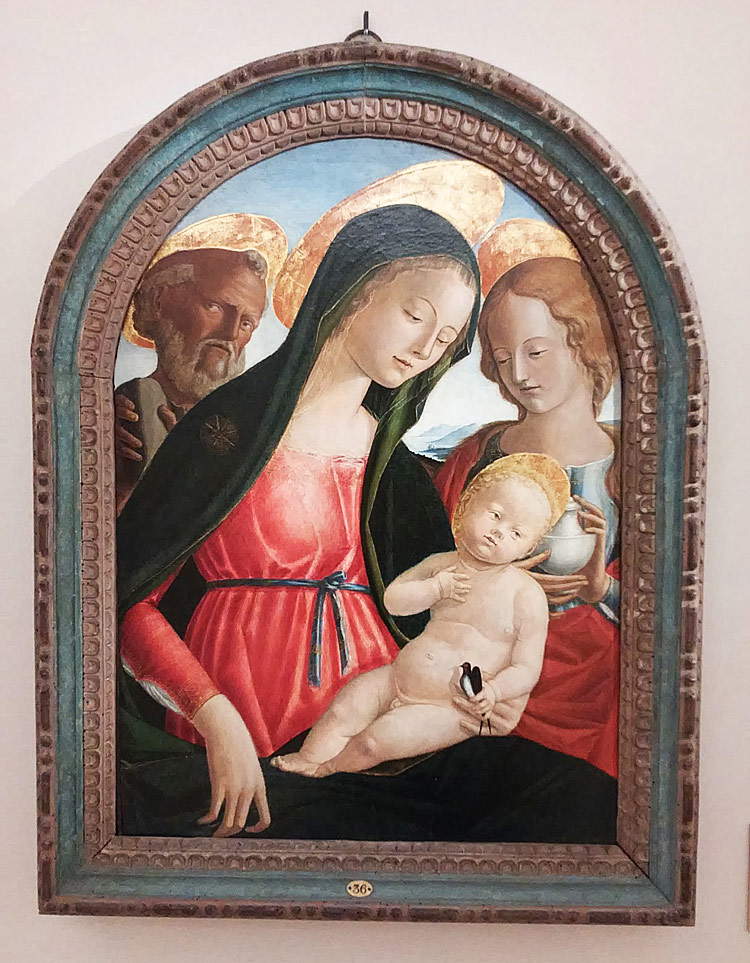

It is also necessary to consider another aspect of collecting at the time: the outflows of works abroad were often compensated by the donations that foreign amateurs left to the Italian state, and the exhibition highlights well this fundamental facet of nineteenth- and twentieth-century collecting. The curator writes in the catalog, “In the usual consideration of the foreign collector as responsible for the export from national borders of many darte objects, we tend to forget the other side of the coin, namely the donations that many foreigners began to make to the Italian state. To the ravenous foreign collector who deprives the national heritage of artistic objects, often with the complicity and in the indifference of local authorities, one must contrast the growth of the national heritage derived from donations from foreign collections, often consisting of works, perhaps Italian, bought abroad and brought back home.” Collectors knew that they had in their hands works linked to the Italian territory, and their precise desire was to ensure that these works remained in Italy. The exhibition therefore displays several pieces that became part of Italy’s public heritage thanks to the intelligence and foresight of the collectors who bought them: a Madonna and Child by Neroccio di Bartolomeo, donated by Herbert Percy Horne (London, 1864 Florence, 1916) along with his entire collection at Palazzo Corsi (in Florence, now the home of the Horne Museum); a Lot and the Daughters by Luca Giordano, part of the collection of Frederick Stibbert (Florence, 1838 1906) also donated to public enjoyment; and a pair of seventeenth-century paintings (including a Christ among the Doctors by Dirck van Baburen) that were instead in the Wurts-Tower collection. These works are particularly important as they exemplify the “attempt at absorption of the Italian cultural heritage” (so Emanuele Pellegrini) that collectors often put into action: an attempt at absorption that pushed them to procure even paintings in which there was very little interest at the time, as in the case of seventeenth-century works (the taste of the time in fact gave preference to gold backgrounds, works by the primitives and Renaissance works).

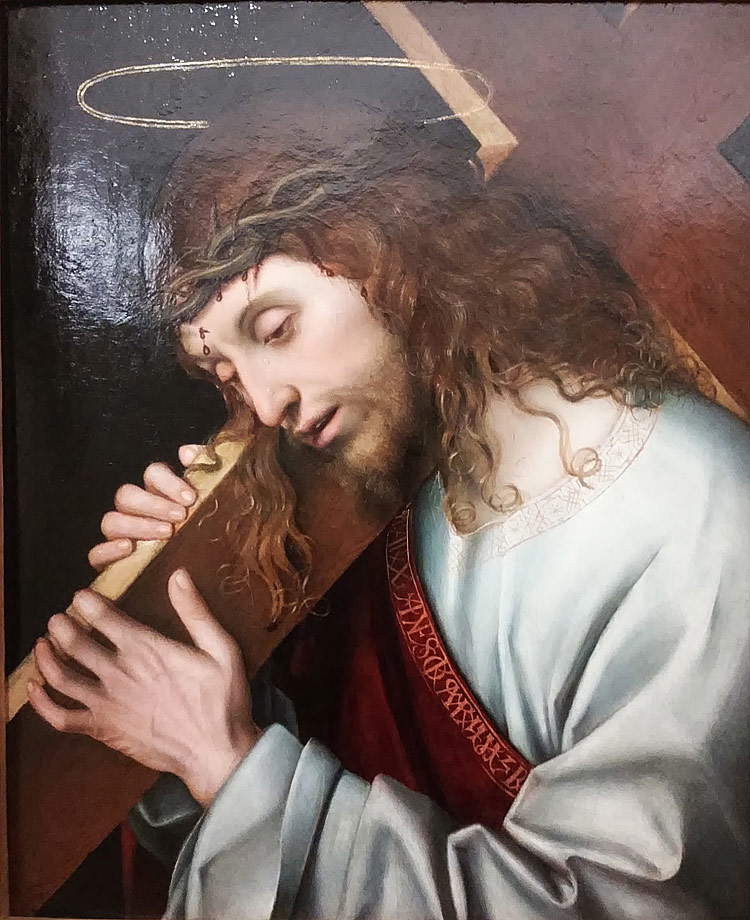

Another interesting element is represented by the exchanges of works of art that were proposed by collectors and antiquarians to the state, in exchange for permission to export certain works of art or a reduction in taxes. This is the case of a Christ carrying the cross by Giovanni Francesco Maineri, now in the Uffizi, which was donated to the state in 1906 by antiquarian Elia Volpi (Città di Castello, 1858 - Florence, 1938), precisely in exchange for permission to export other works. A welcome exchange in the eyes of the state, since, as Corrado Ricci (Ravenna, 1858 - Rome, 1934), then director general of the Ministry of Education (i.e., the ministry that dealt with the subject before the Ministry of Cultural Heritage was established in 1974) commented, the painting is perfectly preserved, increases in importance when one considers the rarity of works preserved in Italy by an artist who is not of the least among the Emilian followers of the flourishing 15th-century Ferrarese school and is appropriate to enrich, in our Galleries, the series of those artists which by the recent acquisitions of works by Tura and Costa has achieved considerable importance.

|

| The three Roman portraits: from left, Male Portrait (mid-3rd century A.D.; Aphrodisian marble from Goktepe, height 39 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts), Portrait of Socrates (Roman copy datable to mid-1st century A.D.; Pentelic marble, height 35.5 cm; Rome, Museo Nazionale Romano), Female Portrait (Antonine age; Luna marble, height 31 cm; Rome, Museo Nazionale Romano) |

|

| Neroccio di Bartolomeo dei Landi, Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome and Mary Magdalene (c. 1496-1499; mixed tempera on panel, 71.5x52 cm; Florence, Museo Fondazione Horne) |

|

| Luca Giordano, Lot and the Daughters (1686; oil on canvas, 122 x 173 cm; Florence, Stibbert Museum) |

|

| Dirck Van Baburen, Christ among the Doctors (c. 1619-1620; oil on canvas, 170 x 210 cm; Rome, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia) |

|

| Giovan Francesco Maineri, Christ Carrying the Cross (post 1506; oil on panel, 50 x 42 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

The exhibition of three important Renaissance works (Donatello’s San Lorenzo from the Silverman collection, Luca della Robbia’s Bust of a Child, and the Madonna and Child of Michelangelo’s scope from the Loeser collection) offers further food for thought. Luca della Robbia’s Child touches on the theme of the birth of the Industrial Art Museums, which arose alongside those industrial art schools that set themselves the goal of “maintaining the high quality of traditional workmanship” and “training craftsmen capable of confronting the needs of the nascent industry, in good substance with the intention of transforming artisans into professionals, and workshops into modern factories capable of imposing themselves on markets far wider than local ones” (Claudio Paolini in the catalog): the Della Robbia work was exhibited, along with a group of Renaissance majolica and porcelain that represented models of inspiration for the artisans of local schools, in the Museo Artistico Industriale founded in Naples by Gaetano Filangieri (Naples, 1824 - 1892), who opened the institute with the twofold aim of ensuring a home for his own collection and endowing his city with an industrial art museum inspired by contemporary European models. The Donatello from the Silverman collection (recognized as the master’s work in 2014) and the Loeser Madonna introduce subjects that the visitor delves into in the following rooms: if with the Madonna the subject of the reworking of the antique opens up, with the San Lorenzo we begin to delve into the subject of shady sales and the shrewdness of the antiquarians who often did not make too many scruples if the aim was to bring in good business. In this case, the work in question was sold by the parish priest of Borgo San Lorenzo (the work was in fact on the main portal of the local parish church of San Lorenzo) to the antiquarian Stefano Bardini (Pieve Santo Stefano, 1836 Florence, 1922), who thought of replacing the original with a copy and selling the real Donatello to Prince John II of Liechtenstein.

The next room delves into precisely that reworking of the antique that was widely practiced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: the workshops of the time did not just create objects inspired by medieval or Renaissance productions (objects on which the words “Made in Italy” often appeared: we find ourselves at the dawn of a history that continues to this day), or to restore ancient works, but often, upon the explicit instructions of their clients, they proceeded with even invasive additions, or with assemblages made through ad hoc fabricated pieces. Definitely interesting is the passage in which the viewer is offered a comparison of two chests, a type of object highly prized by collectors of the time. The first, the larger one, comes from Frederick Stibbert’s collection: it is a caisson that results from the assemblage of several panels attributed to Mariotto di Nardo and coming from at least two different caissons, on a structure that was also heavily restored, as were the paintings (which are totally repainted by Stibbert himself, who affixed his signature on the panels), and remodeled in modern times (the central panel, for example, was cut in half to make an unusual hinged opening). The second, on the other hand, is a modern object by the painter Federigo Angeli (Castelfiorentino, 1891 - Florence, 1952) that is inspired by Renaissance chests and, like Francesco Gentili’s triptych displayed a little further on, marked by numerous 19th-century repaintings, leads the audience to one of the most interesting sections of the entire exhibition, that devoted to forgeries, since often the skills of contemporary painters capable of reproducing ancient works, or of creating works that could very well be mistaken for ancient, were exploited for purposes that were anything but licit. The visitor then learns of the scam that antiquarian Elia Volpi hatched against collector Helen Frick (Pittsburgh, 1888 - 1984) in 1923, when the wily dealer presented and succeeded in selling his client a sculptural group depicting anAnnunciation, which was passed off as an unlikely creation by Simone Martini (corroborated by the monogram “SM” and the date 1316), an artist whose sculptural work, as Gianni Mazzoni explains in the catalog, he invented out of thin air: the work was actually a creation of one of the most skilled forgers of the time, Alceo Dossena (Cremona, 1878 - Rome, 1937), who, with the complicity of complacent antiquarians and art historians, managed to gull a great many collectors, before being discovered in 1928, the year in which the scandal emerged forcefully in the United States of America, the forgers’ favored market. The last room, perhaps the weakest in the exhibition (but well compensated for by a good catalog essay by Vincenzo Farinella), documents how much the interest in antiquities had “infected” the public sector as well: this explains the use of the all’antica frieze to decorate public buildings (including the Vittoriano itself).

|

| Donatello, San Lorenzo (c. 1440; terracotta already painted, height 74.5 cm; maximum width 62 cm; base width 47 cm; Paris, Kathleen Onorato - Peter Silverman collection) |

|

| Luca della Robbia, Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1445; glazed terracotta, 28 x 20 x 18 cm; Naples, Museo Civico Gaetano Filangieri) |

|

| Michelozzo di Bartolomeo’s circle (with restoration additions), Madonna and Child (third-fourth decade of the 15th century; terracotta, 72 x 38 cm; Florence, Museo di Palazzo Vecchio) |

|

| The two chests |

|

| Mariotto di Nardo, Costantino Buonini, Frederick Stibbert, Stories of Crusaders? (c. 1385-1390 and 1870-1871; wooden chest and tempera on panel; Florence, Stibbert Museum) |

|

| Francesco Gentili, Madonna and Child with Musician Angels; Christ at the Pillar; St. John the Baptist (Eighth-ninth decade of the 15th century; tempera on panel, central panel 66.5x39 cm; side panels 66.8x19.5 cm; Assisi, Museo-Treasury of the Basilica of St. Francis) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Announcing Angel (1920-1923; marble, 213 x 228.5 cm; Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Art Gallery) |

Leaving the Sacconi Galleries, one crosses the square and enters Palazzo Venezia to visit part two (or one, depending on how one wants to set one’s path) of Voglia d’Italia. In the first room we are introduced to the figures of George Washington Wurts and his wife Henrietta Tower: Wurts, a high-ranking diplomat who arrived in Italy in 1865, took up residence in Rome in 1870 (although he did not settle permanently in the city until the end of the century, after his second marriage to Henrietta Tower, celebrated in 1898) and after a short time was already well established in Roman society, being able to count on high-level acquaintances and contacts that he was able to maintain throughout his life. The enormous collection that the couple were able to assemble (about three thousand pieces) was displayed in the three residences of Palazzo Mereghi, Palazzo Antici Mattei and Villa Sciarra (the latter was called, in an article published in the New York Times in 1913, “one of the wonders in Rome,” viz: the appellation may suggest an idea of the tenor of the agî with which the Wurts surrounded themselves), and was distinguished by its exceptional variety, such as to make it impossible, as Grazia Maria Fachechi points out in the catalog, “to enucleate typological, chronological, geo-cultural subsets with relative quantifications.” while on the contrary, "it is easy to detect leccectional richness and lestrema varietas of the collection and, through it, the multifaceted character of the curious, ecumenical, systematic, encyclopedic, boundlessly ambitious Wurts, as collectors, sometimes going against the tide in composing areas unexplored by others.“ A broad and eclectic collection, with pieces from all over the world, ”born for the pleasure of possession and seemingly indiscriminate accumulation," in which, however, it is possible to identify certain groups that have a preponderance over others.

The first such group is that of objects of Russian provenance: Wurts, between 1882 and 1892, worked as a diplomat at the U.S. Embassy in St. Petersburg, and soon developed a strong interest in the culture and tradition of the country that had hosted him. His interest, rather than in works of art, was directed toward typical objects of local folklore, or craft productions, and the “Russian” nucleus of the collection reflects the taste for exuberant decoration and the idea of a society strongly tied to traditions, elements that characterized Russian culture at the end of the nineteenth century: hence the marked interest in typical headgear, present in large numbers in the Wurts collection and displayed with abundant examples in the exhibition at Palazzo Venezia. The same desire to preserve objects capable of bearing witness to a culture that fascinated the Wurts had encouraged the purchase of numerous Japanese objects: a passion, that for Japanese productions, which arose following their honeymoon in 1898, which stopped over in the Land of the Rising Sun, and continued over the years, with purchases that the couple made directly on the Roman market, also in the wake of the spread of Japanism, the great passion for Japanese art that had conquered the high society (Roman and not only) of the time. Among the works on display are a large tapestry with two roosters (in their homes, the Wurts made extensive use of Oriental textiles and draperies), an uchishiki with dragons and ho-o birds (this was a fabric for Buddhist altars: the Wurts, however, probably used it as a pillowcase, showing that their interests were not the most philological), a cute porcelain cat as a testament to the Wurts’ many Japanese porcelains, and a large life-size ornamental crane, a popular object in Roman residences of the time: a bronze crane appears in the description of the house of the Marquise d’Ateleta in Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Il Piacere, and it should be emphasized that the writings of the Vate give us a clear picture of what a residence such as that of the Wurts must have looked like at the time, and vice versa, as we walk through the rooms of the exhibition, we cannot help but think of D’Annunzio’s atmospheres.

Another important nucleus is that of the German works, within which it is possible to find pieces of great value: the reason for this passion is explained by virtue of the Teutonic origins of the Wurts family (explored in depth in the first room), which allowed the couple to always remain on excellent terms with Germany (and it was precisely the axis between Italy and Germany that was among the reasons that favored the donation of the collection to the Italian state, not least because the Wurts, moreover, always had good relations with Mussolini). In addition to the bizarre statues of lansquenets, visitors will encounter at Palazzo Venezia a very special St. Michael attributed to Michael Pacher, a daring work whose dilemmas about authorship are, however, far from being resolved, as well as a St. Anne Metterza that features an iconography quite unusual for Italy but particularly widespread in Germany and Austria (St. Anne holds both the infant Jesus and the Virgin on her knees, depicted with adolescent, almost childlike connotations), and a series of fifteenth-century tapestries that are being exhibited for the first time on this occasion. A collection would not have been complete without the so-called old masters, the works of artists who worked before Raphael and who were among the main targets of collectors of the time: a nucleus of primitives formerly in the Nevin collection, then passed to the Wurts in 1907, the year in which the couple purchased part of the American reverend’s collection from the Roman antiquarian Giuseppe Sangiorgi (and most of the Wurts’ old masters were acquired on that occasion), is presented at Palazzo Venezia. Among them, it is worth mentioning a Madonna and Child by Ottaviano Nelli, an early 15th-century Umbrian painter capable of fascinating more than one collector, and a series of refined, subtle, delicate and rare tempera paintings on paper depicting candle-bearing angels: these are figures painted over sheets of paper glued on several layers, about whose function, however, scholars continue to wonder (it is likely that they were hung from chandeliers during religious services).

|

| Russian headdresses |

|

| Fountain in the shape of a crane with its cubs standing among lotus plants with two crabs and a frog (Meiji Period, 1868-1912; bronze casting, 230 x 120 x 70 cm; Rome, National Museum of the Palace of Venice) |

|

| Statuettes of the Lansquenets. |

|

| Japanese Manufacture (Kyoto), Embroidered panel with autumn scene, chickens, maple leaves, and chrysanthemums (late 19th century; embroidered silk and silk brocade border; Rome, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia) |

|

| Uchishiki Tapestry: Buddhist altar ritual cloth, with a design of dragons and ho-o birds (mid-19th century; silk thread, 60 x 65 cm; Rome, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia) |

|

| Kutani Manufacture, Cat (late 19th century, porcelain; Rome, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia) |

|

| Attributed to Michael Pacher, St. Michael the Archangel (carved pine wood, originally polychromed and gilded-sword and scales not original; 93 x 37 x 35 cm Rome, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia) |

|

| Carinthian workshop, probably Villach, SantAnna Metterza (c. 1520; carved lime wood, polychromed, gilded, and silver-plated; 94.7 x 50.2 x 18 cm; Rome, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia) |

|

| German Middle Rhine area manufactory (probably from Cologne, 1465-1480) and unidentified German cartoonist (probably active in Cologne, 1465-1480), Episodes from the Life of Mary and the Life and Passion of Christ (series of four tapestries, with overlapping embroidery; warps: 6 threads/cm; wool and linen wefts; Rome, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia) |

|

| The Angels and the Madonna by Ottaviano Nelli |

|

| Master of the Paper Angels (Lorenzo di Puccio?), Angels Carriers (c. 1450-1460; tempera on paper, 63 x 43 cm each; Rome, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia) |

|

| Ottaviano Nelli, Madonna and Child (tempera and gold on panel, 65.8 x 48.3 cm; Rome, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia) |

A final room attempts to recreate the atmosphere that must have been breathed in the Wurts-Tower home by displaying a series of disparate objects placed next to period photographs depicting them inside the U.S. couple’s homes: a positive conclusion to a clear and well-adapted itinerary for the two exhibition venues, in a coherent manner, with a far more successful scansion than that of the last exhibition held at Palazzo Venezia and a detached venue (i.e., the one on Labyrinths of the Heart last summer). Voglia d’Italia is an excellent, high-level review that rigorously analyzes an important (and little known to the general public) cross-section of art history, which recounts a complex world of merchants and rediscoveries, of antiquarians and forgeries, of laws for protection and illicit operations, which is timely in reconstructing the dynamics that moved Anglo-American collecting in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which also offers food for thought on current events, since the issue of theexport of works of art is as urgent as ever, the latest reform of the sector having been passed in the summer, a reform capable of animating a lively debate, which has been given ample prominence in these pages. Certainly it is not an easy exhibition, but, to tell the truth, there is a great need for exhibitions like Voglia d’Italia, which break out of safe grooves and stimulate the visitor’s curiosity with unprecedented operations, supported by solid scientific projects, capable of delving into little-known but fundamental aspects of the history of our heritage.

The fact that this is a complex exhibition certainly does not affect the fascination that the exhibition is able to arouse: just think of the fact that Voglia d’Italia is theoccasion to return the Wurts-Tower collection to the public, presented for the first time in an organic way. This is an important novelty, considering that the Wurts-Tower collection represents the most voluminous nucleus of the National Museum of Palazzo Venezia. For these reasons, the catalog, published by arte’m, is also a valuable tool for study and in-depth study: more than five hundred pages for the most part devoted to the Wurts-Tower collection, with a good number of works catalogued (the decision not to proceed with a complete cataloguing was dictated by the enormity of the undertaking and by the fact that many Wurts-Tower works had already been catalogued in recent times) and no less than sixteen essays (difficult to present a summary here: these are, however, works that never exhibit any sagging quality, as is sometimes the case) to enrich the discourse that begins in the rooms of the Vittoriano and Palazzo Venezia.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.