The museum, the home of the muses as an open space for sharing with the public, and not a mausoleum where they sing, celebrate and mummify their work. This is how Bianca Pucciarelli in Menna, aka Tomaso Binga, showed up at 94 years old, wheelchair-bound but happy and dynamic as a child, prancing like a ballerina, at Madre in Naples for the first, extensive and organic exhibition about her (opened by herself on April 18, it can be visited until July 21). The title is significant, Euphoria . For it is a word (a privileged form of this artist’s visual art) that contains all the vowels and well embodies the artist’s state of industrious but controlled joy. Only a definition of convenience can describe this proposed exhibition as a retrospective, since the scope of a body of work that began when Binga was about forty years old is still very current and absolutely personal. Personal to be understood as an exhibition of a single author, of course, but the adjective adheres like a tight fitting garment to the figure, the thought, the history, and indeed the body, of Tomaso Binga.

“My masculine name,” said the artist who was born in Salerno in 1931 but has been active in Rome since she moved there in the 1950s, and where she met fellow countryman Filiberto Menna (1926-1989), the critic who soon became her husband, “plays on irony and displacement; she wants to expose the male privilege that reigns in the field of art; it is a contestation by paradox of a superstructure that we have inherited and that, as women, we want to destroy. In art, gender, age, nationality should not be discriminators. The Artist is not a man or a woman but a PERSON.”

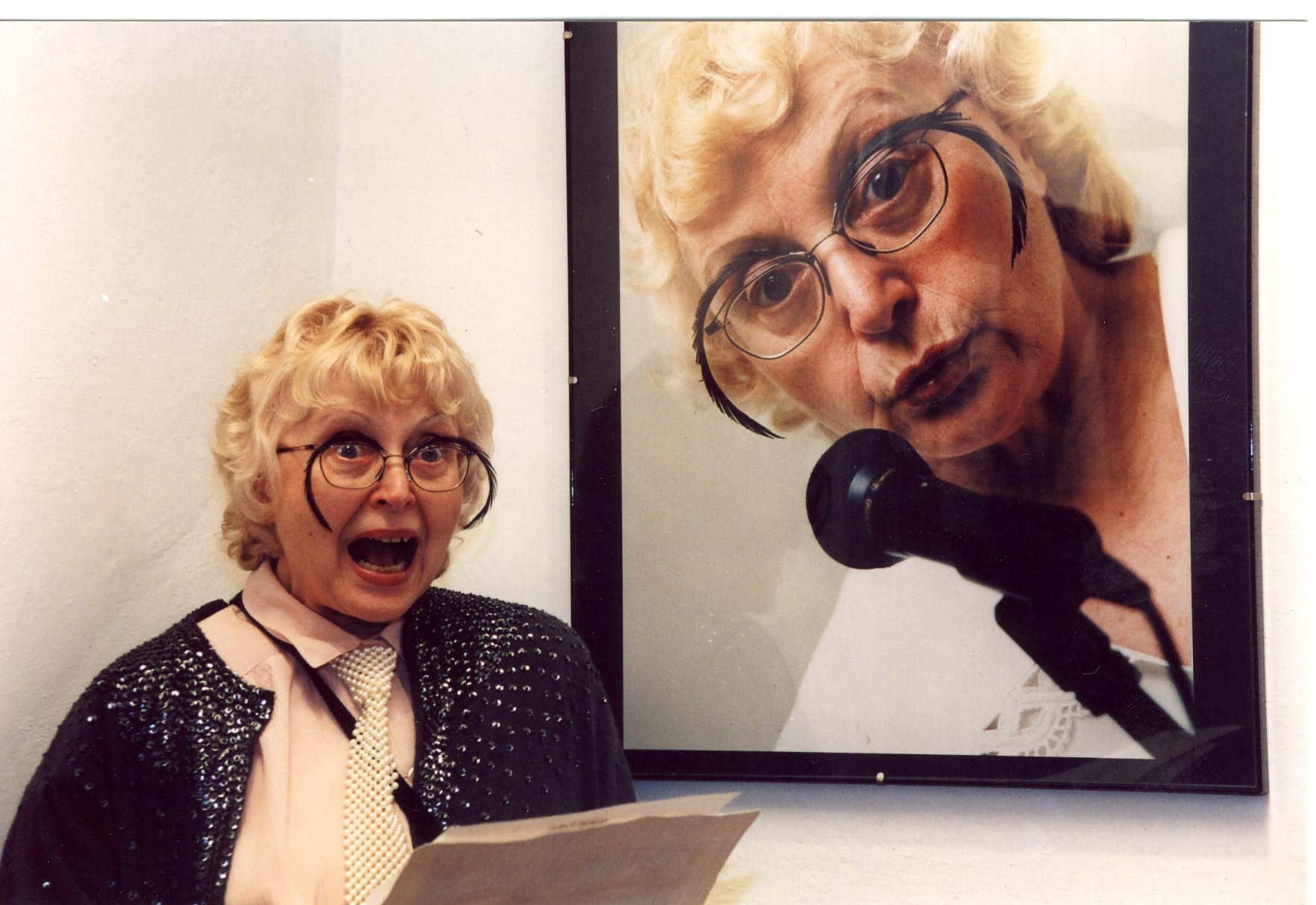

The photo of the artist’s face, with two round cards behind the glasses (which we later find out is a detail of I am...ME. I am...ME, a 1977 work), is printed on transparent plastic sheets that, like fly curtains placed in front of doors, visitors must pass through to enter and exit the exhibition. This is the access key, physical and semantic, to the first of eighteen rooms that on the third floor of the museum on Via Settembrini leads the viewer through the 120 works created from 1960 to the present. A path, a passage through the ideal entry into the body of Tomaso Binga, that covers more than sixty years of work even though only since the early 1970s has his production assumed a precise and programmed identity. First, exhibited in the introductory room, however, there are some interesting pieces from 1960: ceramics or tempera on paper, Untitled and with an abstract language or child of a conscious synthesis of the figure.

This first stage of the anthological exhibition deludes us into thinking that the exhibition is chronological in order, while shortly afterwards we discover that it is diachronic in the cut chosen by Eva Fabbris, who has been at the helm of Madre for the past two years, to curate it together with Daria Khan. Yet the first ceramic masks or the pictorial composition distantly daughter of Vasily Kandinsky (the father of abstraction, who came to art on the threshold of fortyyears old) immediately demonstrates that Tomaso Binga, who chose out of controversy with the male world to call herself by the name of Marinetti, is an authoress endowed from the beginning with coloristic wisdom, compositional skills, and excellent dexterity. In short, the author, who owes a debt to “visual poetry rather than conceptual art” (this is her answer to a question by Luca Lo Pinto in the interview in the book, 300 pages with many photos and several texts in English and Italian, published on the occasion of the exhibition), has from the very beginning, as if she were an easel painter, posed the problem of form.

She, who defines long-practiced perfomance art as a way to “per-form,” immediately declares that art is a specific language. And that it must be declined with care and mastery, even (indeed, especially) when the subject matter has a strong political valence touching on issues and problems such as discrimination and women’s rights (a fine lesson for the new generations who, in the name of social commitment, often neglect the practices of the atelier and the wisdom of the craft).

Extraordinary for example is Tomaso Binga’s ability to deal with a difficult material (because it is cold, light, industrial and impersonal) such as polystyrene, the black beast of every sculptor. In fact, since the early 1970s, the artist has been employing as ready-made packaging boxes made of the white, crumbly polymer in compositions in which the voids are filled with a poetic, but also ironic sense, thanks to photos of mass media culture. And, among the many boxes transformed into little theaters, in which mouths and bodies ripped from the tabloids take center stage, is Oblò from 1972, which entered the collection of the Madre in Naples five years ago.

1972 is also the year in which Binga in Acireale is proposed as a candid sculpture of Vista zero, a talking body in which the many eyes applied to her costume stand to say that the higher the number of viewpoints, the lower the capacity for a deep gaze. And the blow-up of that performance is placed side by side in the exhibition precisely with some totemic and impersonal bodies, assembled and painted in Styrofoam.

Taking the visitor by the hand and step by step through the rooms of the exhibition is the installation created in two years of work by the Rio Grande group (Natascia Fenoglio, Lorenzo Cianchi, Francesco Valtolina) in agreement with the artist. It consists of a red tubular and a pink one (the color of passion and blood next to that of the cloth bows on the doors announcing the birth of a baby girl) that cross the walls of the Madre or are arranged on the ground to support and suspend the works, but also to support as chairs the visitors in the video room with Binga’s performances or with the recording of his poetic participations in the Maurizio Costanzo Show (1995), as interesting and hilarious as those of Carmelo Bene. This architecture, ephemeral and effective, of Tomaso Binga’sEuphoria finds a parallel in the room where his 1973 Landscapes are exhibited, that is, undulating and wavy lines of a horizon, his, never flat.

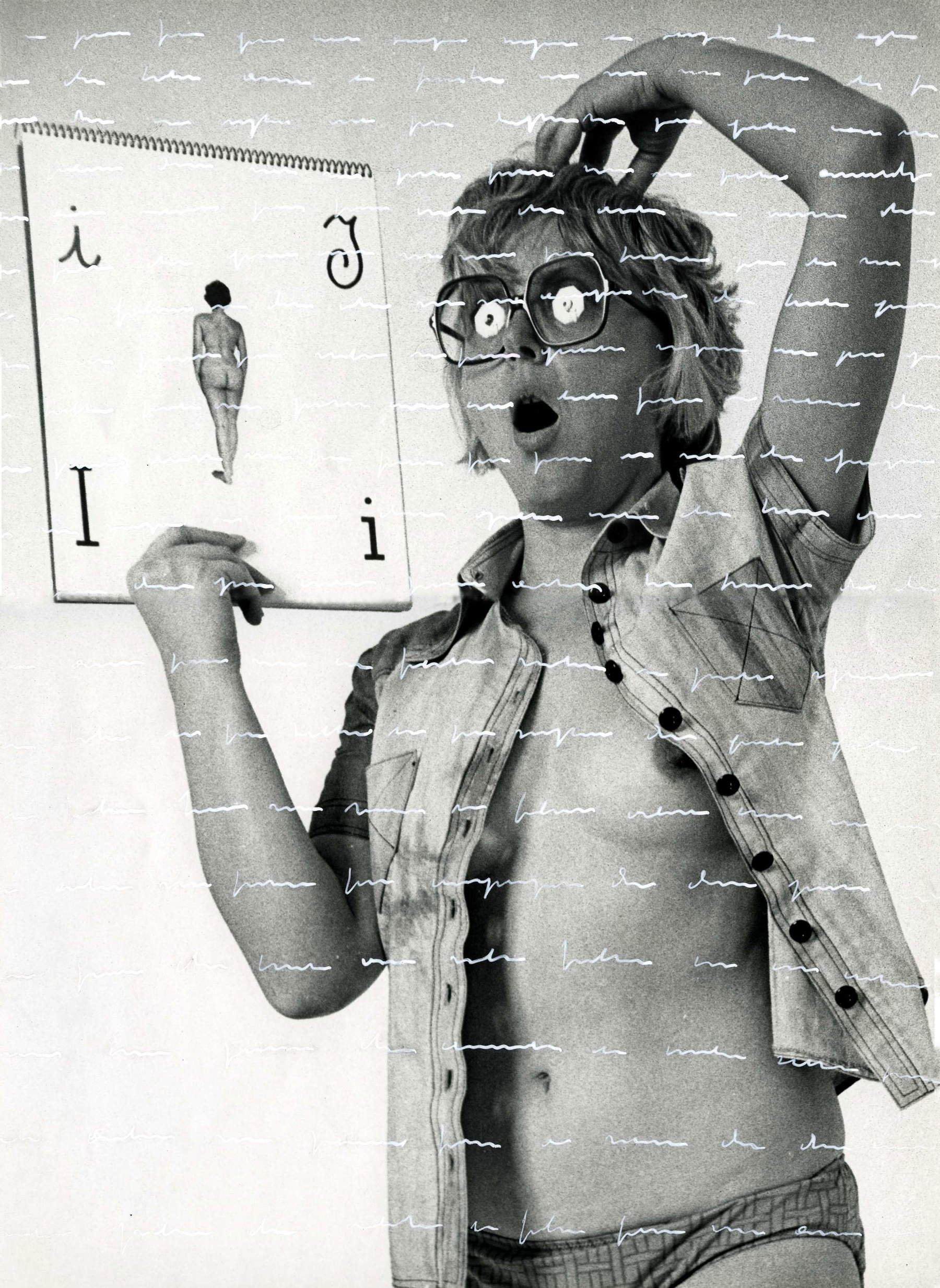

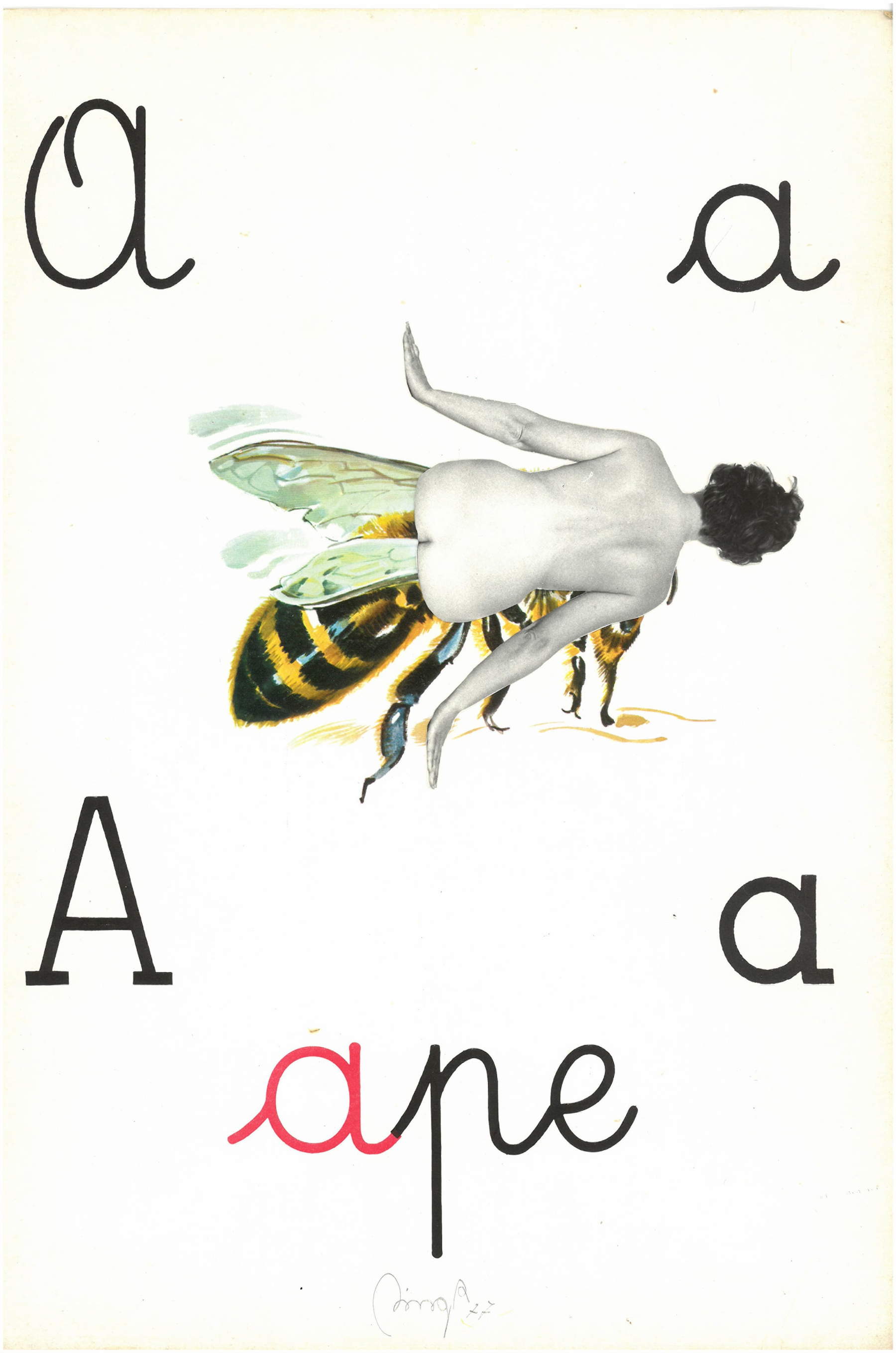

But it is the words that lose meaning, to acquire it as a sign, and the letters of the alphabet interpreted by the naked body of the author who becomes a model, that are the strongest and most recurrent motif in the exhibition of this rediscovered protagonist ofItalian art after years of marginalization by the system and the market (the same fate suffered by two absolute actresses of the Roman and international scene, such as Maria Lai and Mirella Bentivoglio, who would invite Binga, as well as the Sardinian artist, among others, to the important exhibition “Materialization of Language,” at the 1978 Venice Biennale). It was in 1971 that Binga’s cursive first became a line depriving words of their meaning (desemantized writing, an expression of visual poetry). And we have to reach 1974, the year of his first solo show, to see the artist put on a show at the Lavatoio contumaciale in Rome (the space in the Flaminio district, the same as thehome of the Binga-Mennas, run for a long time with her husband then alone with the others and the other members of the group) the performance Parole da conservare / words to destroy (to the experience of this association, also feminist, Stefania Zuliani dedicates an essay in the book-catalogue Stefania Zuliani while Lilou Vidal dwells on the performances and Quinn Latimer on the alphabets).

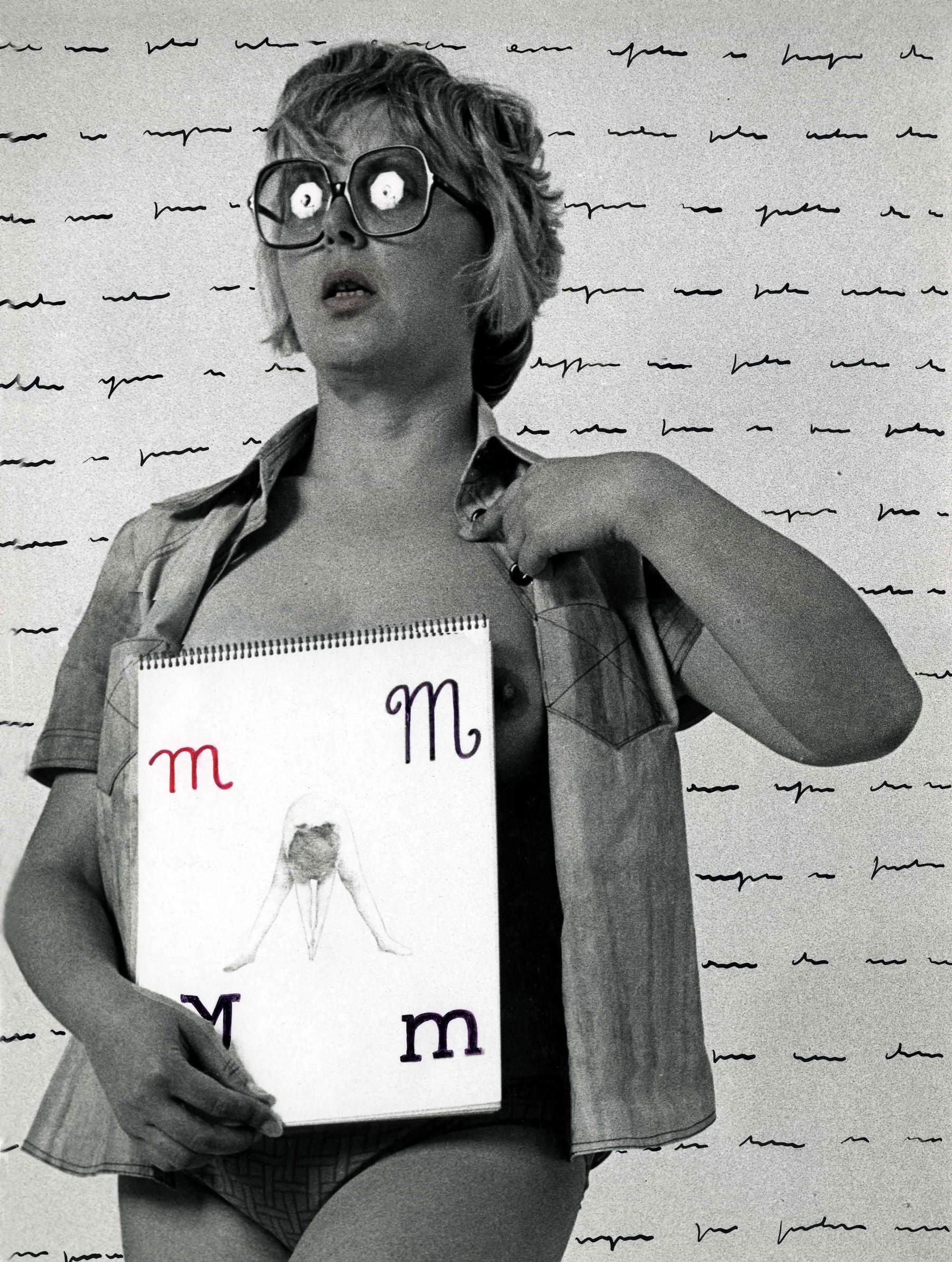

So in 1975 here is theVowel Alphabet followed, the following year, by theMural Alphabet, the first of a long series of plates in which, together with and thanks to Verita Monselles’ photos, Tomaso Binga bends his own body as happened in the human figures in the anthropomorphic (also called acrobatic) capitals of the medieval and Renaissance tradition. And, also playing with the size of the letters (the body, in typographical terms), Binga does so to bring to life his “living writing” in which his own nakedness is the essential component of the letters; letters that can also be understood as missives of that ideal epistolary correspondence that has dictated to the artist works such as I write to you only on Sundays (a day chosen because the only one of the week that ends with an A, like women’s names) or the Roman Diary 1895-1995 .

The Neapolitan exhibition, on the strength of loans from three gallerists (Tiziana Di Caro of Naples, Erica Ravenna of Rome and Fritteli of Florence), but above all of what is preserved in the rich Tomaso Binga Archive, is extensive, detailed, well curated. And the fact that it is engaging is told by the phrases, the writings, the words left in the giant tatzbeao set up at the exit by the artist to collect the voices of the audience, a fundamental element of her horizontal and plural look at the reality of the present. She, who does not consider herself “an artist but one who plays with art,” to the actors in the world of galleries, performances, museums, and media, makes only one remark: “She really lacks self-irony.”

The author of this article: Carlo Alberto Bucci

Nato a Roma nel 1962, Carlo Alberto Bucci si è laureato nel 1989 alla Sapienza con Augusto Gentili. Dalla tesi, dedicata all’opera di “Bartolomeo Montagna per la chiesa di San Bartolomeo a Vicenza”, sono stati estratti i saggi sulla “Pala Porto” e sulla “Presentazione al Tempio”, pubblicati da “Venezia ‘500”, rispettivamente, nel 1991 e nel 1993. È stato redattore a contratto del Dizionario biografico degli italiani dell’Istituto dell’Enciclopedia italiana, per il quale ha redatto alcune voci occupandosi dell’assegnazione e della revisione di quelle degli artisti. Ha lavorato alla schedatura dell’opera di Francesco Di Cocco con Enrico Crispolti, accanto al quale ha lavorato, tra l’altro, alla grande antologica romana del 1992 su Enrico Prampolini. Nel 2000 è stato assunto come redattore del sito Kataweb Arte, diretto da Paolo Vagheggi, quindi nel 2002 è passato al quotidiano La Repubblica dove è rimasto fino al 2024 lavorando per l’Ufficio centrale, per la Cronaca di Roma e per quella nazionale con la qualifica di capo servizio. Ha scritto numerosi articoli e recensioni per gli inserti “Robinson” e “il Venerdì” del quotidiano fondato da Eugenio Scalfari. Si occupa di critica e di divulgazione dell’arte, in particolare moderna e contemporanea (nella foto del 2024 di Dino Ignani è stato ritratto davanti a un dipinto di Giuseppe Modica).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.