Starting Saturday, June 28, and running through Sunday, October 26, 2025, Palazzo Cucchiari in Carrara opens its doors to an exhibition dedicated to play in art between 1850 and 1950: it is entitled In gioco. Illusion and Amusement in Italian Art 1850-1950 and is promoted by the Giorgio Conti Foundation, curated by Massimo Bertozzi. The exhibition aims to explore the theme of play in its many forms, as it was represented by more than eighty Italian artists between the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. More than 110 works will be on display, including paintings, bronzes and wooden sculptures, many of which are rarely exhibited to the public. Of the artists featured, as many as 56 had never before appeared in Palazzo Cucchiari exhibitions.

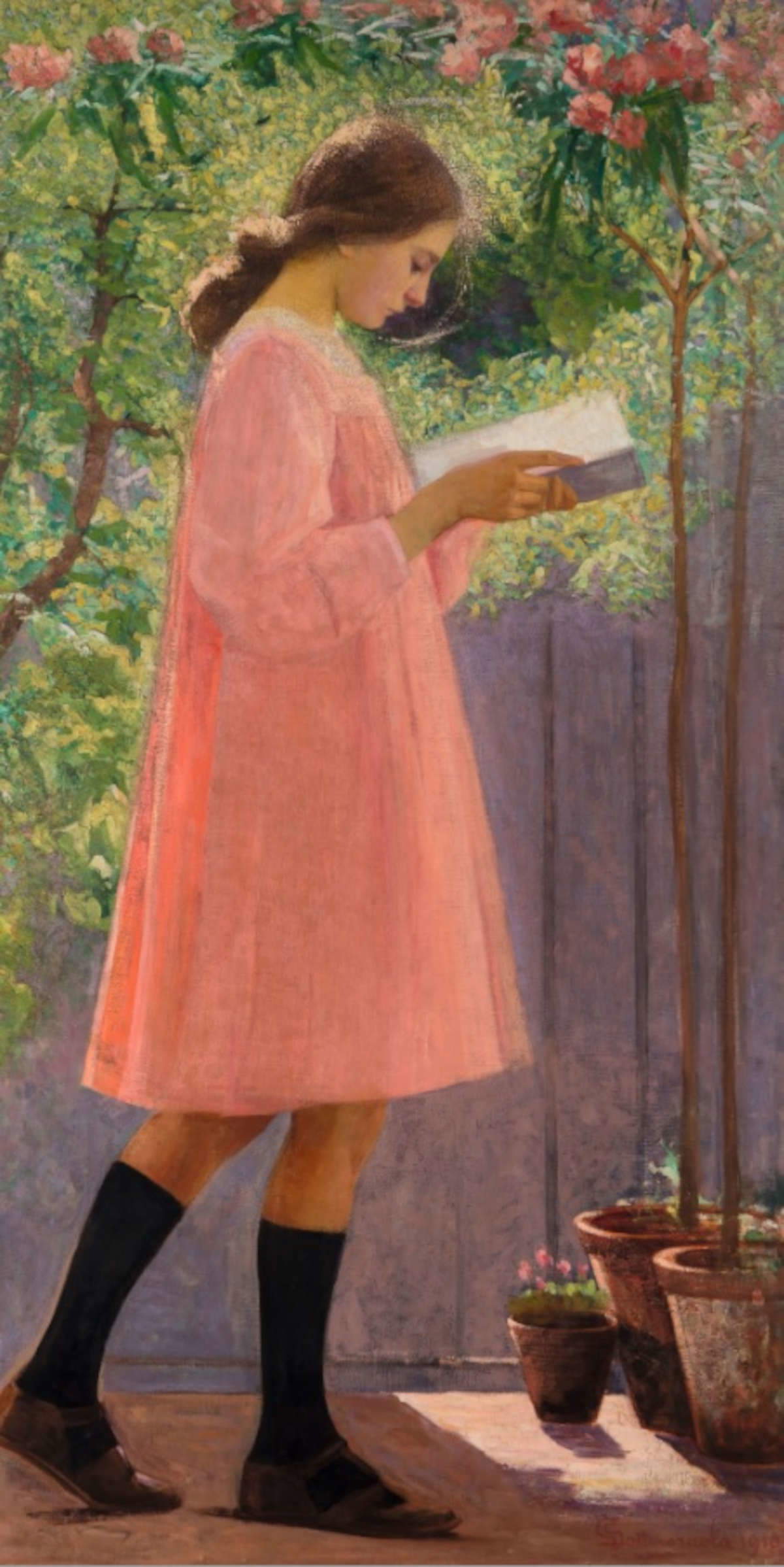

The curatorial intent is to transform the halls of the Palazzo into a “visual amusement park,” where painting and sculpture narrate childhood, leisure, and play as a learning experience and as an expression of modernity. The selection of includes works such as Silvestro Lega’s Le bambine che fanno le signore (1872), arriving from the Matteucci Institute in Viareggio; Carlo Carrà’s La carrozzella (1916), granted by the MART in Rovereto; Felice Casorati’s portrait Cesare Lionello (1911); and Alberto Capogrossi’s Il Baraccone da fiera, coming from the Presidency of the Republic. Among the sculptures, special attention should be paid to Medardo Rosso’s Cantante a spasso, Giacomo Manzù’s Ballerina (1938), Marino Marini’s Nuotatore, Emilio Greco’s Lottatore and Francesco Messina’s Marciatore: works that translate into plastic matter the movement, physical challenge and dynamic elegance typical of the game.

The exhibition unfolds along a path divided into four thematic, nonchronological sections that take the visitor on a broad and evocative reflection on the function of play in art. It begins with Entertainments and Recreations of Everyday Life, then explores Growing Up and Learning: a Child’s Play, moving on to Entertainments and Entertainment: the Invention of Leisure, and concluding with Challenges, Competition and Destiny.

In each section, the works return a broad and layered view of the play experience, between fiction and realism, between allegory and social document. From childhood playing adults in the paintings of Lega or Toma, to boys disappointed by their toys in the melancholy paintings of Pirandello or Francalancia, play takes on the tones of dream, regret, but also social criticism and irony.

A common thread runs through the entire exhibition: the ability of artists to use play to narrate reality, but also to escape from it. In Campigli’s paintings, for example, the memory of ancient games such as hoops resists; while the “miniature world” of toys appears in the works of Casorati and Cagli. And again, the circus and carnivalesque universe comes to life in the paintings of Mosè Bianchi, Gino Severini, Alberto Donghi, Primo Conti and Antonio Ligabue, who give form and color to a dreamlike imagery populated by masks, jugglers, clowns and acrobats.

But play is also competition, chance, spectacle. The concluding sections of the exhibition investigate precisely this transformation of play into sport and performance, with the futurist dynamisms of Sironi, Dottori and Iras Baldessari, the plastic vigor of Marini and Messina, the modern figurations of Carrà and the symbolic provocations of Capogrossi. In these works, play loses the innocence of childhood to become muscular tension, calculated risk, dream of victory or condemnation to defeat.

The exhibition finds its theoretical foundation in the reflections of sociologist Roger Caillois, who defines play as an “uncertain island.” A definition that curator Bertozzi makes his own, defining in turn the game as “a middle ground, between a reality forced to model itself on the organization and rules of everyday life and a country elsewhere, fictitious, but imitated from the real, where the rules have been reorganized and rewritten. A ’magical reality’ where the curiosity of discovery, the pleasure of invention and the whim of creation come to terms with the convention that holds norm and whim together, the same dialectical bickering that unites play and art.” According to Bertozzi, painting and sculpting are alternative ways of playing: both activities are based on fiction, abstraction, and the ability to represent the world according to one’s own codes. Artists, like children, construct rules for the use and consumption of their own imagination: this is how the works on display tell not only about play, but about the very essence of making art.

Through the theme of play, the exhibition traverses one hundred years of Italian history, starting just before the Unification of Italy and arriving at the early postwar years, restoring to the public a complex social and cultural cross-section. In the nineteenth century, the game stops being just a symbol and becomes an autonomous theme: representation of a leisure shared by peasants, aristocrats, priests, women and children. With the transition to the new century, play becomes a nostalgia for childhood, a lost paradise to be evoked through painting and sculpture. Finally, in the twentieth century, modernity transforms play into an institutionalized form of entertainment: live shows multiply, music becomes mundane, carnival becomes a metaphor for social inversion. The concept of “free time” is born, which is no longer wasted time, but a resource to be organized and made productive. Artists respond by narrating, ironizing, sometimes criticizing this transformation.

In the “difficult years” of the twentieth century, the game becomes more and more of a spectacle: sports competitions are established, lotteries and casinos are legalized, and the cult of speed spreads. Sports cheering becomes a mass phenomenon, and artists record it with different sensibilities: some through the deformations of the avant-garde, others with the formal severity of the new Italian classicism.

Sport, physical exertion, risk, the tension of the body in motion: these are the new subjects of the modern game. The works of Sironi, Dottori, Messina, and Marini return this energy in a powerful synthesis of aesthetics and content. Play thus becomes a lens for observing the quality of contemporary life, with its enthusiasms and contradictions.

Hours: 06/28/2025 to 09/14/2025: Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Sundays 9.30am-12.30pm and 4pm-8pm; Fridays and Saturdays 9.30am-12.30pm and 4pm-11pm. 09/16/2025 to 10/26/2025: Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Sundays 9.30am-12.30pm and 3pm-8pm; Fridays and Saturdays 9.30am-12.30pm and 3pm-9pm. Monday closing day. Admission: € 12; concessions € 10; free for young people under 18, handicapped persons, journalists with national ID.

|

| An exhibition in Carrara on play in art along 100 years |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.