Born in 1926, Nino Migliori is one of the most incisive voices of Italian photography. With or without a camera, through analog or digital means, from the 1950s to the present, he has developed projects that transcend the traditional classification of genres, practicing a language that is often close to the poetics of informal, but that has by no means disdained realism, portraying “people” with humanity and affectionate irony. His research is based on three unbreakable pillars: curiosity, the desire to experiment and creative freedom. We met him in his atelier in Bologna to talk about photography, his relationships with other artists, critical positions and his most emblematic projects.

MS. Nino, when did you first pick up a camera?

NM. As soon as the Second World War was over, when we regained the freedom to move, since in addition to the conflict we had to suffer the restrictions of the regime. Moreover, freedom has always been the Leitmotif of all my production: I have always been free from patterns and genres. In the mid-1940s I was 19 years old and photography allowed me to get to know my city, which has always been my gymnasium; however, I had no money to buy a camera so I borrowed it. Soon, however, one of my photographs won first prize in a competition at San Domenico and so I was able to buy my first camera.

You claim that Bologna has always been your gym, but in your photos it is difficult to recognize the city. Why?

Because I photographed Bologna through its inhabitants, not through the monuments. Moreover, already in the late 1950s I started working on walls, the crumbled ones, with writing, with torn posters. For me the walls were closely connected with people because they constituted a kind of diary of the inhabitants of the city. Those who wanted to communicate with someone else and had no other means, what did they have at their disposal? A piece of chalk and a wall on which to affix writings and figurines. The surface thus became his notebook of memory, of lived experience. I documented these walls by considering them as the medium for writing and presenting oneself especially of young people who had no books or other places to express themselves.

Walls were then, and still are today, a privileged surface for political messages, whether through writing or images and street art. Were you interested in these expressions?

In the 1950s, the writings were more personal than anything else, while in the 1970s they became mainly political. I photographed walls for 30 years, then I stopped firstly because they began to identify me with that subject, to label me. Secondly, in the early 1980s graffiti artists began to appear, and in my opinion their writing no longer expressed a political feeling or gesture, but the aesthetic component prevailed. And the walls stopped attracting me.

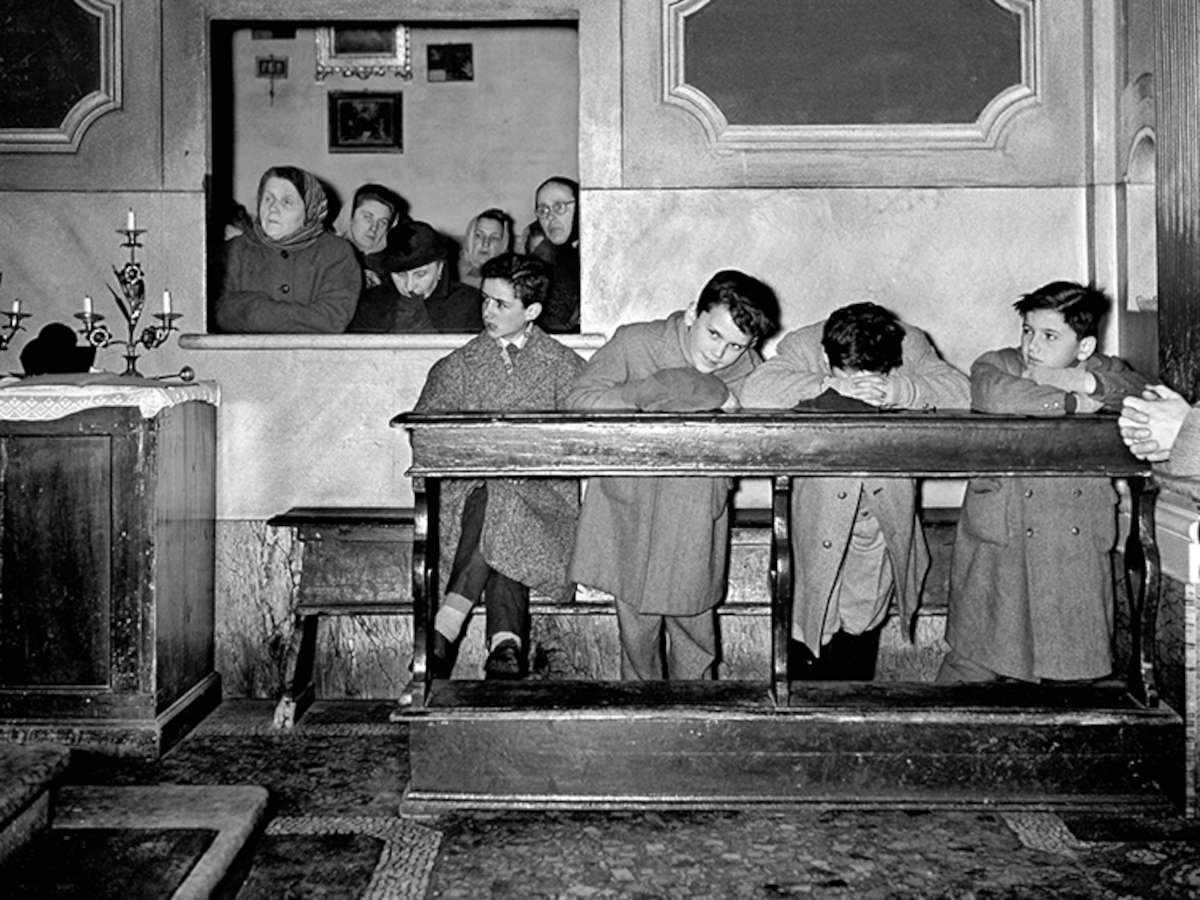

Also in the early 1950s you made some of your most famous cycles, such as People of Emilia, People of the Delta, People of the South. Were these commissioned projects or did you make them spontaneously?

That of realist photography was my second line of research, contemporary with the others. My projects have always been independent, not commissioned: I could afford it because actually my job was something else: I was commercial and artistic director for some companies and then an official at Fabbri, the black cherry company. All this gave me the freedom to always do what I wanted and how I wanted.

What do you think are the hallmarks of your “realist” photography?

My series from the 1950s should not be considered with the nostalgic eye of “the way we were,” and comparing them with those of De Biasi, Reuter, etc., you can see that each photographer has a different look. I can say that my gaze has a strong component of irony, as is evident, for example, in Intermezzo: there are the bride and groom in front of a church in Bologna, there is a man passing by with balloons, there is the official photographer and me ruining his picture! Or in the shot Milan (1954) I framed a deserted intersection, but in the center is a policeman standing upright and motionless on his platform, waiting for someone to arrive. In addition, I have always tried to capture the different planes in the photographs, so that the viewer has the impression of “stepping into them.” In The Bar at Night there are multiple directors of people, the first, the second, and then there is a third, so the threshold of the gaze is always moved further. And speaking of gazes, those of the subjects depicted often become the protagonists of the photos: they are often gazes that turn in different directions, as in the shot that depicts a group of people in front of the store “Hairdresser for Lady.”

Let us come then to the third factor of your research, the experimental one.

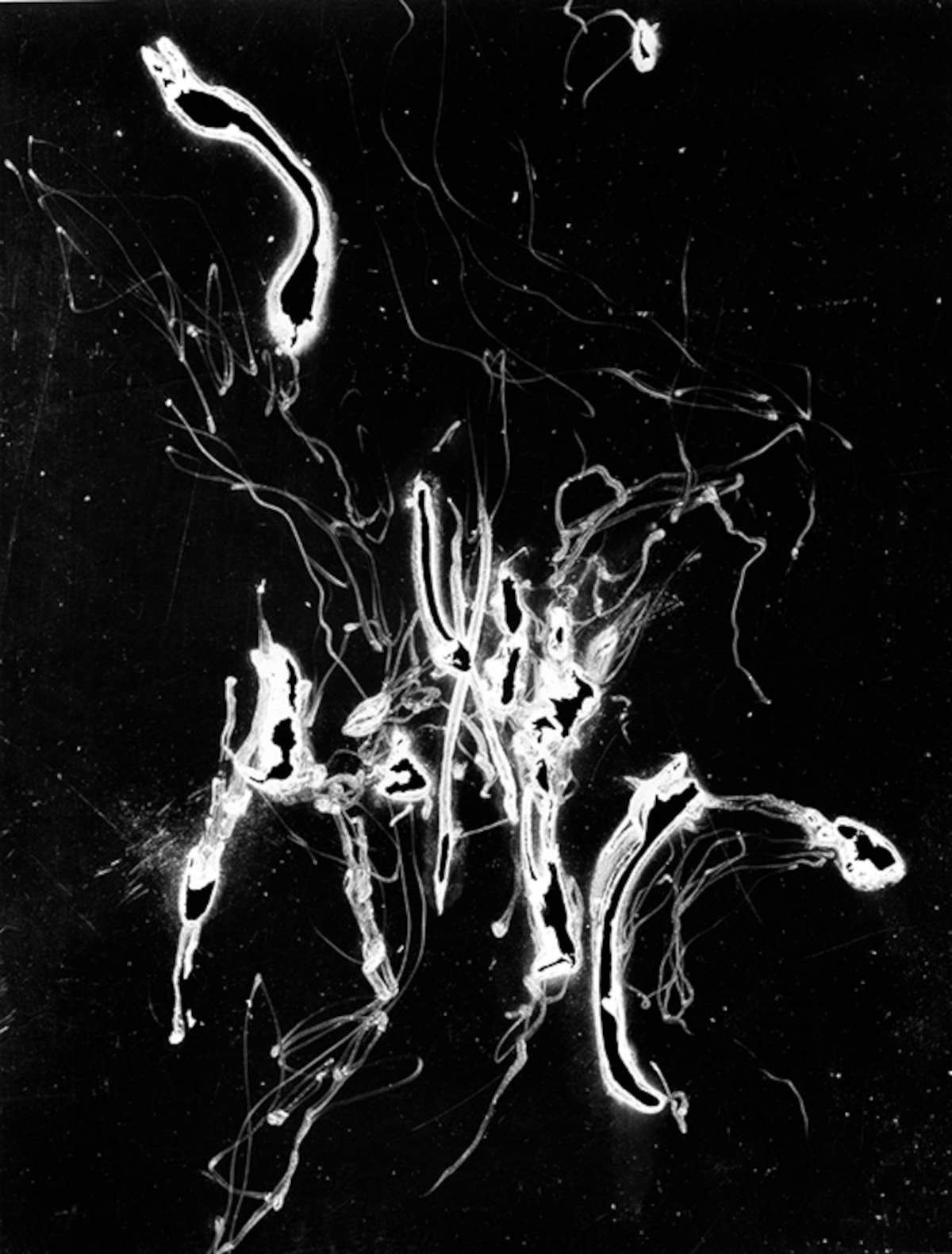

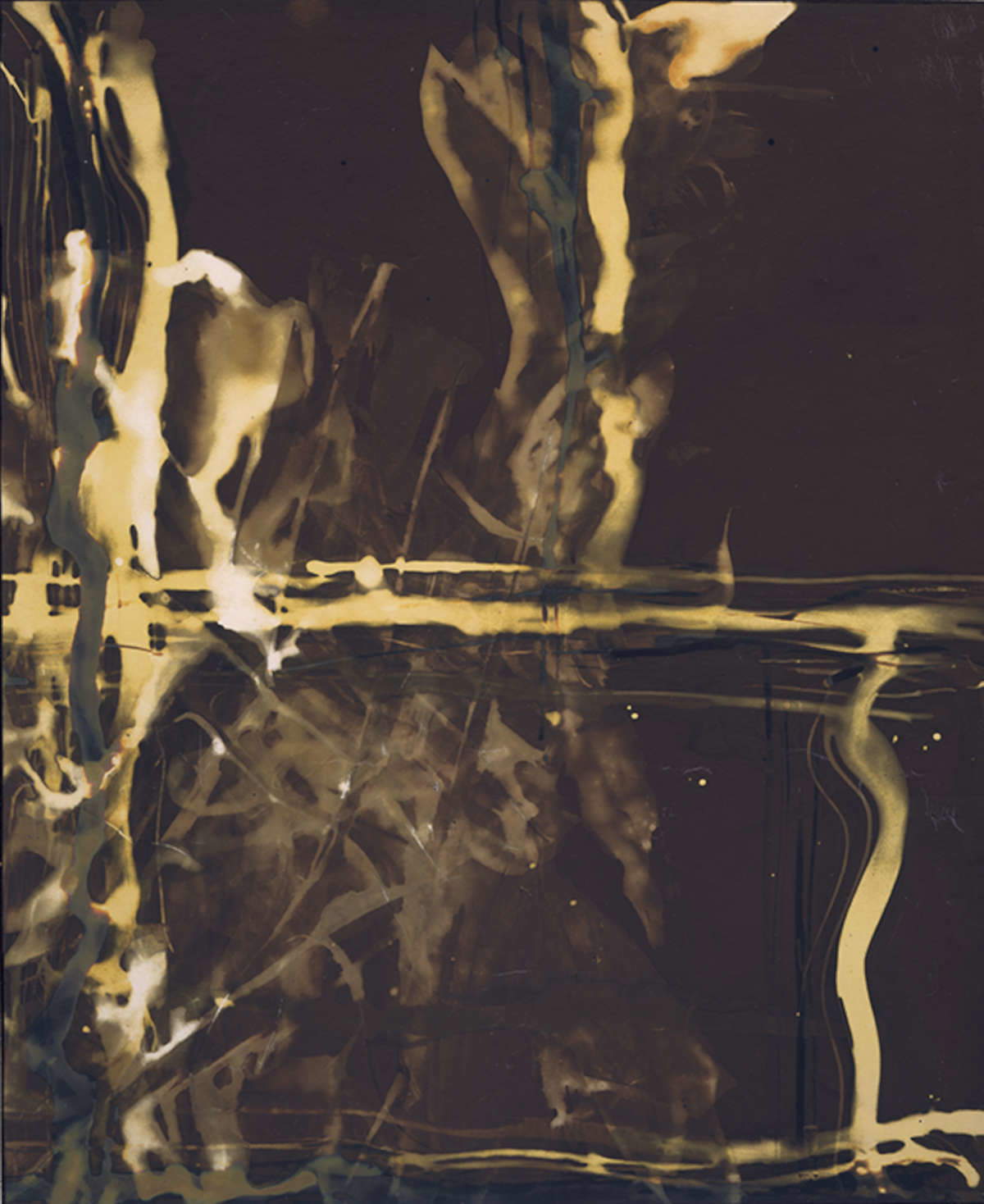

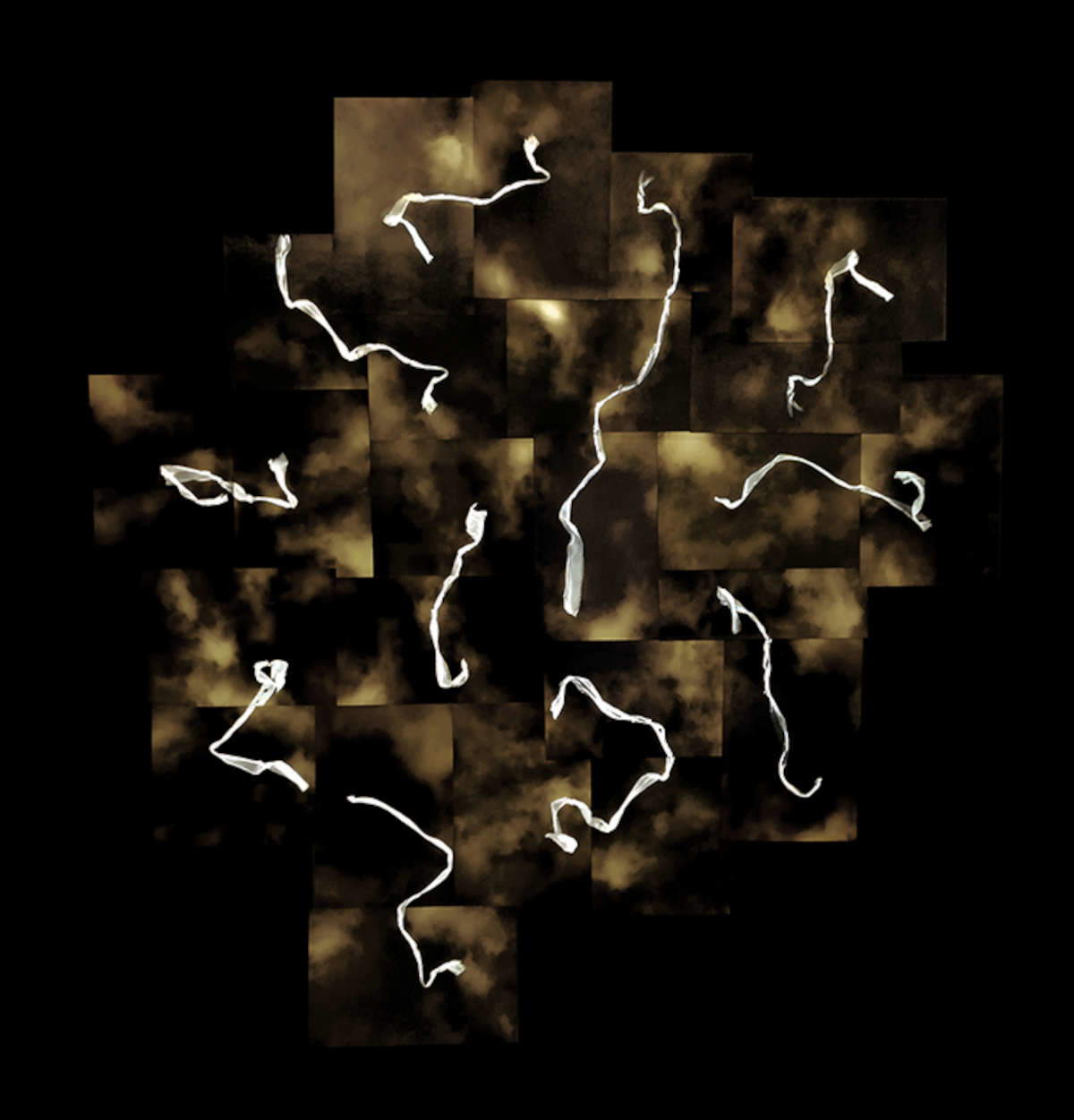

The interest in experimentation began by chance. Also in those years I was a member of the Circolo Fotografico Bolognese, and printing one’s own negatives was a strong point for any amateur photographer: the quality of the print was part of the game, and so at night the bathroom became the darkroom that was dismantled in the morning. Of course, one printed in black and white, but one day I found a proof of a colored print and said to myself, “But how? I use black and white papers, why is the paper colored?” The phenomenon was caused by oxidations: before getting to white, in fact, silver salts go through various shades. This greatly amazed me and so in 1948 I devoted myself to my first experiments: the Oxidations are made without a camera, directly on photographic paper with development, fixing, heat and light. Then I made the Pyrograms, burning the negatives and then printing them on paper.

Regarding the walls and Pyrograms, it is almost inevitable to think of the research of Mimmo Rotella and Alberto Burri. Is there any relationship that unites you?

I started working on torn posters before Rotella. I photographed them because they represented, like the writings, people’s gestures and they are linked to the passage of time, like the chipped walls; so they came from a different idea than Rotella’s, which instead has an aesthetic purpose. Even with regard to the burns, my interest is always traced back to the gesture and the observation of how the heat of the pyrograph or flame interfered with the film. However, the Oxidations and Pyrograms certainly fit within an informal poetics that was being expressed by many artists in Bologna.

Did you have close relationships with artists in the postwar Bologna context?

Yes, because within the photographic circle all these experimentations were systematically dismissed, they were not considered photography. The painters, on the other hand, understood and appreciated them, just as I appreciated their work. I frequented Vasco Bendini, Luciano Leonardi, Vittorio Mascalchi, Concetto Pozzati, Pirro Cuniberti, that is, many of the exponents of the informal current of that time. They were avant-garde artists and gave me the support to continue in my research. Bendini was a few years older than me and the others, and he was considered somewhat the leader, perhaps even the most structured; in the 1970s Pozzati was also very successful.

Were you the only one among this group of artists who expressed himself through photography?

Yes, I was the photographer. I was actually hanging out with these young painters as well as with historical artists like Pietro Scapardini and Giorgio Morandi. I was very curious then and used the camera as a picklock to open secret doors, to understand who these established artists were, how they behaved and why they did those things. I was also very close friends with poster artist Sepo, even though he was older than me, and many of these friendships lasted a lifetime.

However, you didn’t just gravitate to Bologna--your biography mentions your attendance at Peggy Guggenheim’s house in Venice. What impact did that experience have?

I was also friends with Tancredi Parmeggiani and Emilio Vedova, and the latter, when I went to Venice, used to put me up in his studio; I slept in a sleeping bag, we didn’t even have money to go eat. They were the ones who insisted that I meet Peggy Guggenheim. I then took many portraits of her, which she appreciated, and today some of my pictures are kept in the Collection. That was a golden period ... I still remember the evening when a Pollock work arrived unexpectedly: the hostess was enthusiastic and Vedova also expressed himself very positively.

The 1970s also saw the emergence of installations: did you make any during that period?

For me photography is a language with which I can narrate, and I can do it by writing a couplet or a kilometer-long novel. So sometimes one photograph can tell everything, and sometimes I need a series of shots. In the latter case the photos can become the basis for installations, and I have made some of them since the 1970s. I consider particularly important Subtraction and Accumulation of Memory (1976) for which I reproduced famous photographs of violent scenes on transparencies and superimposed them until the image became completely black; or, by a reverse process, I lightened them to the point that everything became white. The violence was still there, but you could no longer see it: the sense of course is that the more we see violent gestures, the more we get used to them and no longer perceive them. Another installation is also from 1976 and was shown only in my solo exhibition in Parma the following year. It was called Lo specchio (The Mirror) and visitors entered a dark room equipped with a flashlight and approached objects hanging on the walls, that is, mirrors on which violent photographs were still leaning: those who mirrored saw themselves and the violence, as if they were part of it.

You have a definite critical stance of both photography and art more generally. In particular you are against idealist aesthetics and photographic salonism. Can you elaborate on what you mean by that?

You have to keep in mind that the photography that met the taste of the 1950s was the one that played on aesthetics. Even Giulio Andreotti had condemned neorealist cinema or “neorealist” photography because they represented a poor, miserable Italy that was not to be popularized, such as the one that emerges strongly from the Gente del Delta series. By the way, I emphasize that I have never followed neorealist cinema, and actually neorealist photography does not exist: instead, realist photography exists. Today we look at those images with a romantic eye, but back then they were breaking photographs. People were living in houses that were little more than shacks, women were fetching water from the river, there were still signs of bombing: it was a completely different world.

And what do you mean by “salonism”?

In the 1950s photography existed mainly in photographic circles, there were very few professional photographers and they often went abroad to work. The circles were the place, all over Italy, where you could discuss photography, meet other photographers, participate in competitions. But the photos that were exhibited were those of composition, strongly aesthetic and formal, while off-camera experimentation was not accepted.

When did you begin to be recognized for experimental research as well?

The first to consider my work as a “reasoning” about photography was certainly Arturo Carlo Quintavalle in 1977. Since then my photography began to be appreciated.

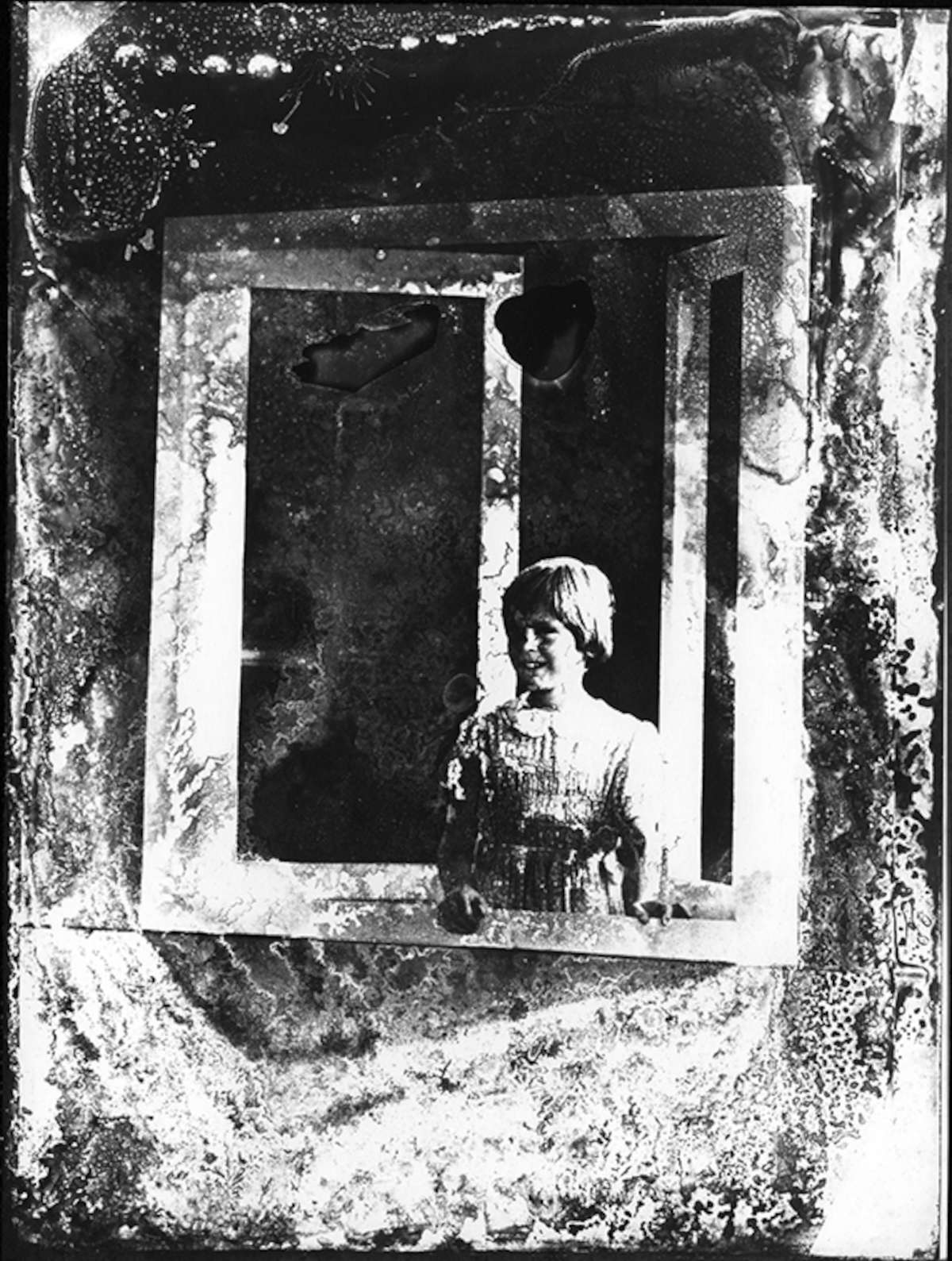

Your reflections have led you to develop a real critical position. Can you describe it for us?

Precisely to affirm my critical position in 1968 I developed the project Antimemory , which I consider a turning point. In addition to the circles, in fact, I frequented the large Villani studio that developed the photos of all the people of Bologna and where we also discussed photography from different points of view, for example commercial and industrial since it was a corporate reality. One day at Villani’s I found some photographs that were going to be thrown away because they were ruined. I took them, printed them as is and signed them, titling the series Antimemory because it is not true that photography is memory, since with time the print and the negative get ruined, so progressively they lose their memory. And in any case it can only represent one’s own memory, the one one wants to see. Here then, genres do not exist because a work such as mine can belong to more than one genre-I have in fact used portraits, newspaper photos, reportage, travel photos and so on-and this reflection has been a watershed in my research.

Are there other works that clearly reflect your thinking?

The other project that is very clear in that sense, however, is Segnificazione of 1978. In 1975 I had been called by Carlo Bertelli, who was then the director of Calcografia, to do a work together with the artist Guido Strazza and the poet Giulia Nicolai, and each had analyzed the graphic sign according to his own language. In the end Bertelli gave everyone something as a gift and gave me a print of Guercino’sEcce Homo made with the pantograph. I began to photograph it, identifying details consisting of many dashes and simply enlarging them, without altering them: the result was images that at first glance look like Lichtensteins, Vasarely. Or I printed the reproduction ofEcce Homo with a much more pronounced, Caravaggesque contrast, or toned down to the point that it looked like the work of a madonnaro. Thus I wanted to show-and at the time it was not a given! - that photography is a lie, because what you see is only a portion of reality interpreted by the photographer. In short, mine was a demystification of the rendering of reality through the medium of photography.

I would then link back to Guercino to introduce the theme of candlelight photos. How did you come up with that project?

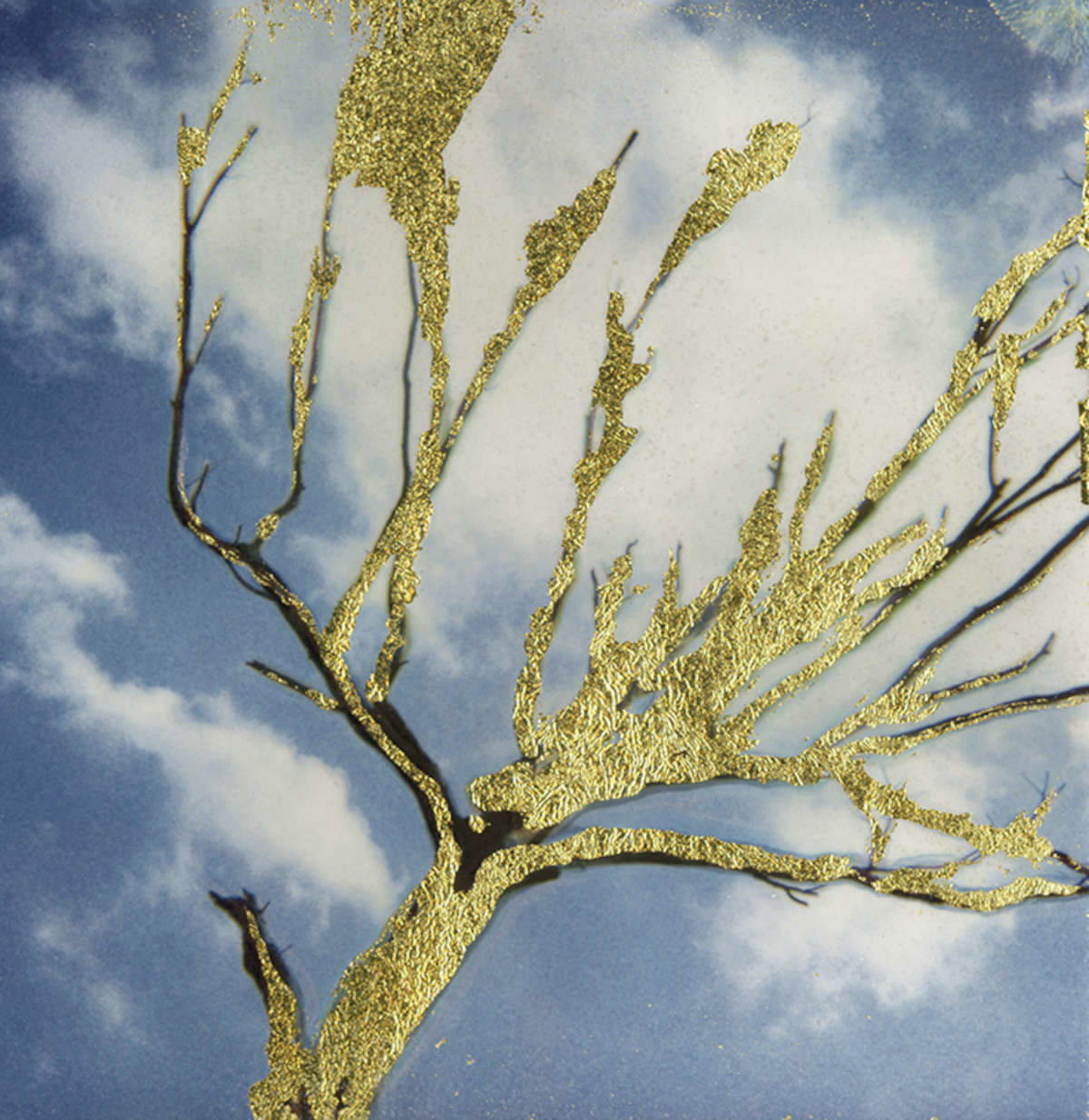

The idea dates back to 2005, and the first work was made in 2006. The then dean of the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Parma, Ivo Iori, was curating a series of volumes of unpublished works and asked me for a project, telling me to open the drawers of my archives to find something not to be published. But I wanted to do new work, and since the basics of architectural photography (static, view camera, etc.) did not belong to me, he suggested that I focus on the Zooforo of the Baptistery of Parma. I then reflected on how people, in times past when there was no electric light, saw works of art. At night the streets were dark and those who passed by could only see details or little more thanks to flashlights or candles. This is how the Lumen project came about, and the first series depicts precisely the bestiary running around the medieval building.

How did this project continue for so long that still in October 2023 you “portrayed” the Fonte Gaia in Siena?

A few years after the first series I made other candlelight sequences. In Bologna, Superintendent Luigi Ficacci gave me the go-ahead to photograph the Lamentation of Niccolò dell’Arca (1463-1490, ed.), and then, when he was transferred to Lucca, he proposed that I devote myself to the funeral monument of Ilaria del Carretto (Jacopo della Quercia, 1406-1408). Later, I portrayed the lions and metopes of the Modena cathedral (12th century), the Veiled Christ in Naples (Giuseppe Sanmartino, 1753), the Zodiac of the Malatesta Temple in Rimini (Agostino di Duccio, 1447-1457), and Paolina Borghese in Rome (Canova, 1805-1808), whose photographs are still virtually unpublished. My enduring interest stems particularly from the fact that each work is produced with different materials, which react to light differently, so each time is a challenge, I never know exactly how the light will look. For example, Paolina Borghese is covered with a very thin layer of pink wax to give the idea of skin, so while it is true that the sculpture is white marble, it is not completely white. Ilaria del Carretto, on the other hand, has a somewhat ruined surface, while the Lamentation is in terracotta. Lumen ’s last subject was instead the Fonte Gaia in Siena, the originals of which are in the Santa Maria della Scala complex: these are pieces, especially those of the base, which are quite ruined, and this fascinates me because one of the common threads that accompany my research is a taste for the informal.

How did you experience the transition from analog to digital?

My experimental vocation meant that the transition from analog to digital was not traumatic, on the contrary. If photography is a language, then changing medium does not change the substance of my work. The propensity for experimentation led me to welcome new tools with curiosity, to see the new possibilities they offered without fear or resistance. After all, it is always about storytelling, playing with light, with image, with meaning.

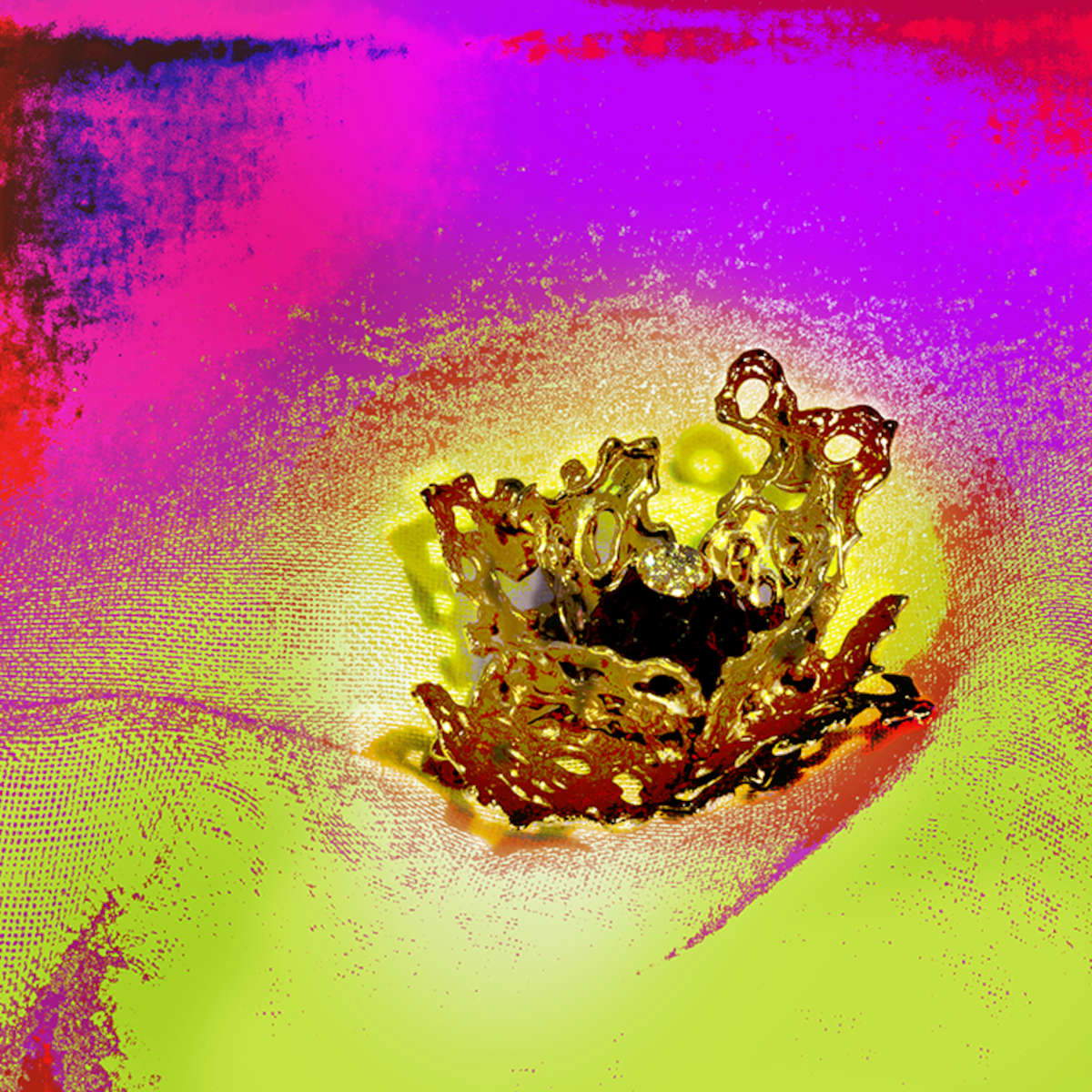

When did you start using digital tools?

My approach was through scanners, starting from old experiments done with the Polaroid 600. The instructions said that you absolutely should not touch the “sandwich” once the picture was taken, until it was fully developed. I, of course, wondered: if I cut off the edges and open it what do I get? Two things: the front film where the image is, and the back film which is completely white because it contains all the chemical components that went into developing it; but because I was processing Polaroids, it also contained all my gestures. So I had kept the backs, although I didn’t know what to do with them. Once I had a scanner, I tried to scan the white part, which is actually rich in colors in power, and thanks to photoediting programs I derived the layers, which were very colorful: the Transfigurations series was born. Then I used digital in the classical sense as soon as the cameras guaranteed a good yield.

And what do you think today about image generation with artificial intelligence?

I have always thought that as long as light enters a camera or is used on a sensitive medium, allowing an image to be fixed, then photography will exist, which does not depend on the analog medium or a numerical ratio, because it is literally “writing light.” Photography generated with artificial intelligence is therefore no longer photography, since it needs neither light nor creativity, that is, the second factor on which a photographer’s work is based.

The last question is about teaching: you have been very committed to “photographic literacy,” including to children, right?

Literacy work always starts with the youngest children and then continues with older kids and adults. I did a lot of off-camera techniques workshops with both children and adults and never asked to be paid, but if there were funds available I would direct them toward publishing the participants’ work. To literate people to photography is to teach them how to use light.

The author of this article: Marta Santacatterina

Marta Santacatterina (Schio, 1974, vive e lavora a Parma) ha conseguito nel 2007 il Dottorato di ricerca in Storia dell’Arte, con indirizzo medievale, all’Università di Parma. È iscritta all’Ordine dei giornalisti dal 2016 e attualmente collabora con diverse riviste specializzate in arte e cultura, privilegiando le epoche antica e moderna. Ha svolto e svolge ancora incarichi di coordinamento per diversi magazine e si occupa inoltre di approfondimenti e inchieste relativi alle tematiche del food e della sostenibilità.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.