With the return of art fairs in attendance, we are back to discussing the market landscape and the Italian scene. Among the protagonists of recent times is certainly Milan’s Dep Art Gallery, among the most active even during the pandemic and ready to present itself to the public with a new program and quality exhibitions, in a market (the Italian one, but also the international one) that is changing. In what way? We talked about it with Antonio Addamiano, director of Dep Art Gallery. The interview is edited by Federico Giannini.

FG. Dep Art has just returned from MiArt: how was the fair?

AA. It went well, as we did not expect such a large audience response and such a high quality. Obviously, today’s fairs reflect a bit the way the public approaches them: whereas in the past people used to come to the fair already with the idea of selling, now the idea is to present the gallery’s program, to show new work, their artists, or to talk about future events or past exhibitions (and in our case catalogs). So there is no longer a sincere expectation to close the sale in a few minutes and a few hours. But the fair still remains crucial for contact. With the large audience that was at MiArt, I must say that the balance is positive.

How are contemporary art fairs changing? Do they still make sense, or at least as we have known them so far?

Definitely they make sense both for those who have, like us, a primary market and for the secondary market, because fairs still remain the first meeting place to present their artists and tell about them not only through price, but also their language and their research, as well as the gallery itself. On the other hand, it also serves gallerists who make secondary market, that is, buy and sell, to let people see the work live and discuss live negotiations having a more complete idea of their interlocutor. In addition, fairs are also important because selling online is very difficult: we can just manage to sell the artist of the moment or the most accessible artist. For everything else, the fair and gallery work are crucial. In addition, a fair in the city like MiArt is even more important for all the galleries in Milan, because there is much more possibility that the public of the fair will then come to see you also in the gallery (we for example this week have more or less one appointment a day).

As for the public and collectors, however, after eighteen months of no fairs, have they changed the way they approach buying or even simply meeting the work proposed by the gallery?

I have noticed mainly (it may also be because I moved from the modern area to the contemporary area) a change in the age group: those between sixty and eighty years old have decreased, perhaps because of contagion risk issues, and there has been a new flurry of collectors in their forties and sixties, who have often approached this world because during the pandemic they became informed through the Internet, or because they had time to cultivate a passion for art. This was a bit of a surprise. Basically we saw a different kind of collector, a new generation. I can’t say whether it was created by the lockdown, by staying at home, by getting informed, by the many articles about art as an investment, about art and design, or even because there was a rediscovery of the home (many, they had the opportunity to renovate or buy beautiful new pieces of furniture and even artwork), but all of these elements had a strong impact. A crisis was then definitely felt, however, not for all sectors from which buyers come, so art, fortunately, always manages to save itself because there are niches of people among customers who work in environments that continue to function even during crises. In the case of the pandemic, pharmaceuticals, banking, and real estate have been three very strong sectors in these eighteen months, perhaps at the expense of all the clients we had from catering and fashion, or notaries, lawyers, and dentists. So there has been a shift in the composition of the clientele: there has been much more interest from new categories of workers than from the more traditional ones. You can sense this by doing a trade show, because on the Internet, the customer sends you an inquiry and you respond, without knowing the profession. In person, customers tell who they are and you realize who you are dealing with.

As far as nationality is concerned, has anything changed? Did you see some international audience at MiArt or was it mainly an Italian audience?

There was much less of an international audience: if before it was 70 percent Italian and 30 percent foreign (composed mainly of Americans, Asians and Europeans) now it’s the ratio is 90-10. And the 10% were Swiss, Germans and some French.

Could it have influenced the fact that the week after MiArt was Art Basel?

No, because at Art Basel (I was there on Monday) I had the same feeling: many people coming from various parts of Europe, because it is still very complicated to move from the United States or Asia. In the end you all left from your own country and neighboring countries. Then in each state there are so many events, so at least this year you are very happy to visit your own fair. Then there is also to say that every national fair (be it Italian, English, French, Chinese, American, Swiss) always has a range of international artists, never lacking a cosmopolitan outlook. The Italian public can come to Milan and have a wide range of offerings. Many of our galleries have several foreign artists, and there is no longer a need to go abroad to meet them. This has also changed a lot because, even just ten years ago, there was a majority of Italian artists at MiArt.

In Italy there are three main fairs (Artissima in Turin, MiArt in Milan and Arte Fiera in Bologna), of course each with its own identity its own specificities: is this an advantage for the sector or can it be somewhat penalizing?

It is an advantage because the scene is very diverse: there are three main fairs, two other more recent and quality national fairs (the one in Verona, and the one in Rome that is about to be born) and a dozen or so fairs that cater to a local audience and small collectors. As a calendar, in my opinion, that is more than enough. Local fairs give visibility to small galleries, partly because the ratio of spending on them is 1:10. For a booth in a “small” feria you have an expense around 2,000 euros; in a larger fair you need 20,000. I met young people in their 20s who wanted to make their bones: do we tell them not to exhibit at local fairs? I myself started that way. If you can “read” them, such fairs are a good school. You have low participation fees, meet the first collectors (and even the first “smart ones” sometimes) and get trained. You don’t get a lot of exposure for your artists, because exhibiting in a secondary fair creates fewer opportunities, but it is beneficial for a young person who wants to gain experience. The three fairs in Turin, Milan and Bologna give greater visibility to the artist, and therefore serve both the artist and the gallery, because they are must-attend events for high-profile collectors and established curators.

As for Dep Art, we were saying that at the fair it experienced this change of direction from modern to contemporary. Why this choice?

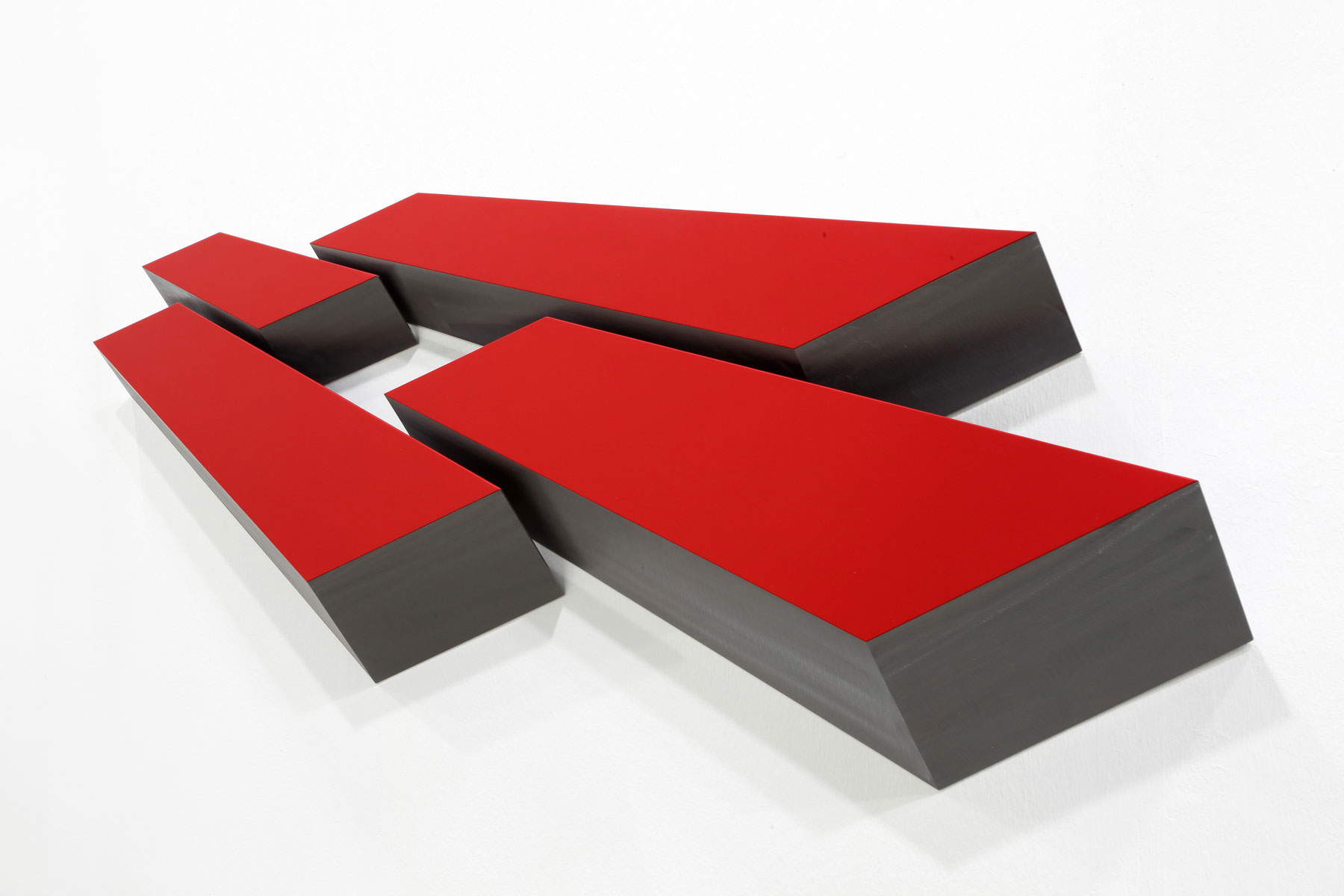

Because I wanted to be in the area of the fair where colleagues deal with the primary market, where the gallerist works closely with the artist or his or her foundation. In the modern, the client’s profile is more prepared, as a dynamic of art as “investment” is activated: in my case, clients would have known that works by Cruz-Diez or Biasi have valuations around 140-200,000 euros. In that case, there is no surprise effect in the client, because they are aware of the caliber of the artists in the booth. In contemporary, we found ourselves explaining who an Italian master like Biasi was. It was worth it, though. And then there is another consideration to make: in the modern section, both De Bellis and Rabottini never had recent works by the artists exhibited, but only up to the 1990s. This has long penalized us with Wolfram Ullrich: although he is the most important artist for us, who is successful at fairs because he has incredible appeal in person, the works from the 1990s do not fully represent him; they are outdated works. The curatorial change that took place in this edition of MiArt 2021 allowed me to exhibit Ullrich with works that testify both to his evolution, from 2000 to the present, and with works specifically designed for the event.

For an Italian contemporary art gallery, what are the biggest difficulties today?

Definitely the taxation regime we have in Italy. Compared to other countries, Italy facilitates contemporary art galleries very little, at least from four points of view: import VAT, SIAE, VAT on sales and Art Bonus. None of these four elements facilitates contemporary art in Italy, which is why so many galleries are based abroad, where it only takes a few transactions to realize the convenience. Imagine the works of the international “big boys”: paying 10 percent import, instead of 5 percent as in other countries, and adding 22 percent VAT, does not make Italians competitive in a globalized market. The Art Bonus is only for museums and renovations and therefore does not help young artists either. These are the initiatives of the National Association of Modern and Contemporary Art Galleries toward the government. At least grant one! Because otherwise there is no future, and that is just a shame. In Italy we have a very high quality of artists, perhaps among the best in the world. And I hope that, sooner or later, the government will at least give us a signal. I’m not saying solve all four of the problems I pointed out, but at least one. Because we are increasingly distancing ourselves from international realities. I was last Tuesday in Paris: you can just see a completely different evolution, in proposals, in the size of galleries, in the number of employees. Here we are saved only by the ability of the gallerists (there are so many good ones!) and the great quality of the artists. We have incredible untapped potential, and I don’t understand why institutions don’t realize that it would be enough to emulate our neighbors. We don’t have to invent something new. Even on funds to support artist residencies, awards, new generations, there is no real interest in supporting such proposals. There is a lot of focus on supporting museums-which is fine, because we have a unique museum offer in the world-and for most people it makes more sense to fund Pompeii or the Colosseum, rather than the private or youth art system. A generation with incredible potential is being lost, though. The inducement that these large public places of culture create is not questioned, but that of a large gallery is no less. We gallery owners are very much like fashion: we could reach very high levels, be an industry capable of attracting visitors from abroad. I am not just talking about buyers, but a public that discovers and falls in love with Italy thanks to contemporary art galleries. Yet it seems that the ministerial leadership does not care about this. Not to mention the difficulty of export, which is the only point on which we agree among art galleries, auction houses, philatelists, antique dealers, and design galleries. It would be time to revamp the export law, which currently restricts the circulation of even non-historically significant works of art. The environment is beginning to fear a collapse in economic values: if you go from selling your artists all over the world to focusing exclusively on the Italian market, prices will automatically drop, because the international clientele will be lost, with the subsequent devaluation of the work on the market. From my point of view, emphasis must be placed on this problem.

How is Dep Art coming out of these eighteen months of enforced blockade?

The focus has been to complete and implement the digital department with the material on hand from the last ten years, making it interactive. We already had a good base thanks to our social platforms (especially Instagram, Facebook, and especially YouTube, where we were already present), and we were able to implement them with the inclusion of two technicians (a video maker and an editor) in the gallery and two other people who were involved in the translation of the material, to make it as international as possible. In the meantime, we went on with very good gallery programming, produced beautiful exhibitions and catalogs, while now we are back to the exhibition interface. We had a drop in income, but that was matched by a drop in costs, because in the gallery the fairs were taking up 70 percent of the annual expenses. So we had a positive balance, coupled with a growth in staff: there was a lot of time to be together, to work as a team, and to have major content development. It was actually not such a bad period for us. It has been more so for artists whose works need eye contact: obviously not all artists have the same results on the web. In our case Wolfram Ullrich, the first artist in terms of sales in direct situations, has dropped palpably, being able to refer only to viewing via digital platforms.

To conclude, what plans do you have in the immediate future?

We will soon open the exhibition of Imi Knoebel, a great international artist who lives and works in Düsseldorf, who has been absent in Milan for 30 years, (his last exhibition was at PAC in 1991). It is with great enthusiasm and honor that we had the opportunity to realize this second dream of mine (the first was Carlos Cruz-Diez two years ago). The pandemic caused a lull, where many important international artists (such as Imi Knoebel) suffered an inevitable slowdown, such that it was possible to submit our exhibition to him in the gallery by establishing a fruitful and honest dialogue. The fact that a proposal of mine came to him in a difficult period was very much appreciated by him: I went to Basel to meet him precisely because we also wanted to understand how happy he was with this project, to create a meeting point, and he expressed his happiness and convictions. Working with a young gallery, which has come through this period and which can be one of the galleries of tomorrow, is of great interest to him: having carefully curated the layouts and the published catalogs, which accompany each exhibition, certainly had its weight. So on October 7 we’re off to a great start again, and we’re looking forward to it.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.