by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta, published on 07/10/2018

Categories:

News Focus

/ Disclaimer

October 6 largest-ever demonstration for culture work: the faces and stories of those who were in the square, the claims, the proposals.

The freshness, the resolve, the high and proud gaze of those who have just entered the world of work, already assaying all its contradictions, but with the desire to try to change the course of the game by playing their cards to the best of their ability and with conviction. The pride, the dignity, the anger of those who instead take on the many years of experience and fight as much to secure a right to the future as to solidarize with their younger colleagues, to help them, to support them. Piazza Mastai in Rome, the end point of the Oct. 6 demonstration, the largest ever for cultural work, is a melting pot of different stories. An early autumn Saturday morning that began under the sign of pouring rain but did not stop the three thousand workers who took to the streets to demand better working conditions, recognition of their professionalism, more adequate economic rewards, and above all to emphasize how essential culture is in the life of a democratic country.

That of culture is a procession that unites. Italians and foreigners. Young and old. Different social classes. Even different political affiliations. Also, all professions. In Piazza Mastai there are actors and musicians, archaeologists and art historians, librarians and archivists, dancers and theater artists, and even professionals from choirs and orchestras, directors, workers from television, museums, communication publishing, there are restorers, anthropologists, historians, and there are also many students who have come to Rome from all parts of Italy to join the workers in a great embrace of solidarity that transcends ages, social differences, and cultural origins. As we take some photographs we find Laura, a young entertainment worker, who stresses the importance of this unity. “This is the first demonstration in Italy of our sector, and it is the first time we are witnessing such an intense unity of all cultural workers. It is important to stand united, because united we are better able to deal with the issues that affect us, from exploitation to cuts to labor shortages. From this square we want to rebuild something so that we can assert our rights. And as a basic assumption there is the fact that culture is important for the development of a fairer, freer, more critical society.” Elizabeth, a restorer, echoes her. She recently finished her studies. “I did a PhD,” she tells us, “and then ... a year of volunteer work. I never had a steady, stable job.” And in fact Elisabetta might even be entitled to that fixed, stable employment she dreams of, because in 2016 she took part in the Ministry of Cultural Heritage’s competition for the profile of restorer: the tests ended in November 2017, and since then she and her colleagues (almost two hundred in all) are still waiting for the rankings. “It’s been a year now, and they have been keeping us suspended for a year. But, speaking more generally, the problem is that not enough is invested, there are very trained people who cannot find a job despite the fact that our cultural heritage needs a lot of care.”

|

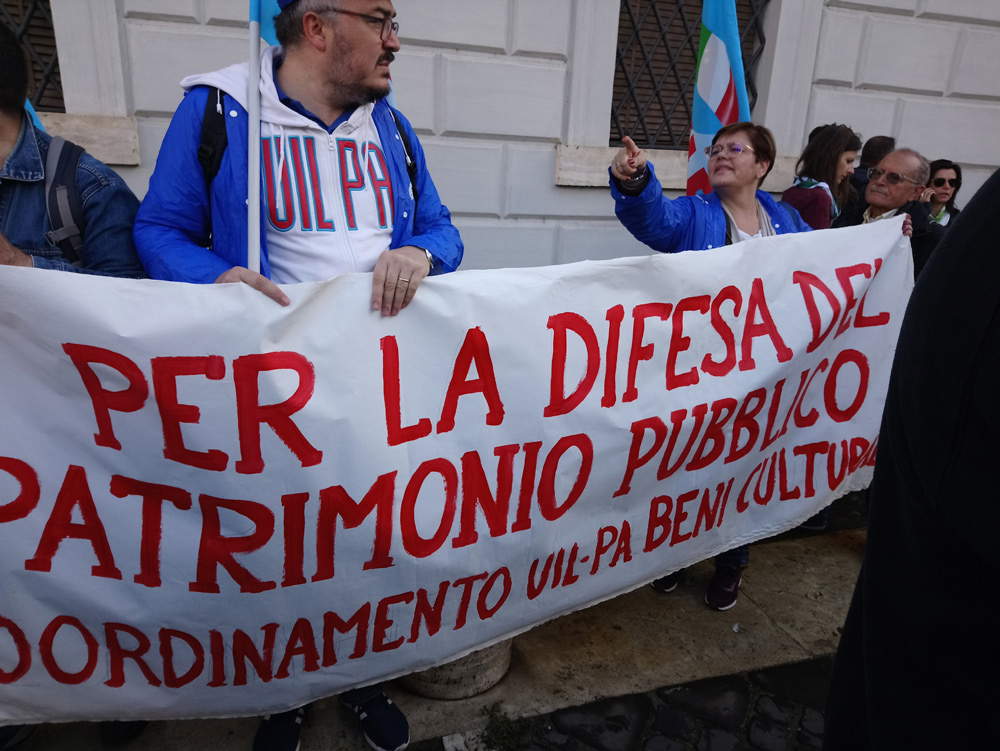

| Moments of the October 6 demonstration for culture |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

And while there are many, like Elisabetta, who do not have a job and would like one, there are also those who already have a job, and perhaps even a stable one, but are aware that there is little interest in the field by politicians. Giuliano, for example, is a worker at Carlo Felice in Genoa and came with his group precisely “to highlight the fact that there is little attention to this sector of ours. Our experiences with the previous minister were disastrous: it sounds bad to say it, but so far those who were supposed to safeguard culture have only done damage to our sector, and now we can only hope that those who have just arrived will do better than those who preceded them. Because the continuous cuts to the FUS, the Single Fund for Performing Arts, have thrown many of us into precarious economic conditions. Without money, theaters do not go forward.” Elena, on the other hand, works at the Superintendency of Cagliari and is in the square with her colleagues because after the Franceschini reform, working conditions have become more difficult: lack of turnover, unified competencies and therefore more chaotic situations, and, the other side of the coin, the staff that used to be under the Superintendency for Cultural Heritage divided between the new “holistic” superintendencies and museums. “We are here protesting,” he lets us know, “because we are asking for the abolition of the Franceschini reform that separated the museums from the superintendencies and unified, as if they were the same thing, totally different activities such as archaeological, landscape and artistic heritage protection, and consequently we are asking that they give us the autonomy we need to work. Because now we are cannibalizing each other, and we are not working well.” In the square we also meet those who had a job, however precarious, and lost it. We run into two of the Magnani-Rocca Foundation workers at the center of the case that rose to national headlines a few weeks ago. “We are here to demand better working conditions, to have a minimum of protection,” they tell us. “Because from one moment to the next we found ourselves without work. And until now our story is the story of an underpaid precariat in the cultural sector, without any kind of protection or guarantee, in the face of a high but unrecognized level of professionalism. A precariousness that has lasted for almost eight years.” The two young women, both art historians, are challenged. “At the moment there are no prospects for the future. We keep sending out resumes but in our field it is really very difficult.”

Then there are a lot of very young faces: some of them still sit among the benches of the university, while others, despite their age, have already had negative experiences. As we finish an interview, a young man notices us and asks us to tell his story. His name is Fabian, he is only 20 years old, he came from Bologna, and he is a musician. So far he has been working with co-production contracts: in his case, he tells us, companies have always offloaded part of the entrepreneurial risk onto him, asking him to meet part of the production costs. “We musicians, in Italy, are simply not considered workers, we don’t have a statute. I would like it to be known that ours is a very unexciting situation. Often, the venues where we perform and the record labels do not pay us, but even ask us to pay: the companies ask you to pay something and ask for percentages on the sales of the songs, or even the venues, in order for you to play, want to be paid. I have seen venues that paid all their workers, from the bartender to the flyers for the evening, except the musicians. In Italy, unfortunately, this is how it is: we musicians are considered a bit like court jesters.” Actors also narrate entirely similar events. In the square we find Carolyn, a young actress who has recently started working but is aware of the problems she will be facing and is already struggling with. As speakers take turns on the stage in Piazza Mastai, she tells us about her experiences, “we often find ourselves dealing with declared and unpaid rehearsals. And especially with a labor system that hardly provides for regular contracts. Sometimes even just joining a company would be enough to have some extra security. Instead, many of us are called only on a show-by-show basis, with contracts that are limited to the single show. And this lack of continuity will not allow us to reach a pension in the future.”

|

| Moments of the October 6 demonstration for culture |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

As mentioned, students also took to the streets to support workers. And there were not only those studying in the humanities: Marco arrived from Padua together with a group of friends. He is a medical student, but with all his other fellow students from every course he shares uncertainty about the future. “I’m here because many of us, despite years of study and highly specialized and professionalized training, and then after years of sacrifice, often cannot find a job that can pay them back. This I think is a problem that affects all fields. And then, even though I study medicine, I am convinced of the fundamental importance of culture for our country. And so it is the duty of all citizens to ask institutions to do more for culture.” Among the students we meet Camilla, who is part of the university coordination Link, one of the many entities that have pledged their support for the October 6 demonstration. “We are here in solidarity with cultural heritage professionals but also because we are the ones studying today to become archaeologists, archivists, art historians, museum workers, restorers, and we see an absence of a way out of our study paths, in the sense that we are told that we must continue to train after graduation, however, they do not offer us great possibilities. Postgraduate training is all made up of very expensive paid master’s degrees, of graduate schools that we don’t really know what they are for because they are a repetition of the previous path, and by the way they don’t even provide a system of right to study, so those who cannot afford them cannot access them. That’s precisely why, seeing what’s next, between exploitation of cultural work, work disguised as volunteer work, the impossibility of imagining a worthy future, we are here in this square. And then we are here because our universities, our courses, our cultural heritage courses, are put at risk: the university has undergone an ever-increasing process of defunding, and it is precisely the humanities faculties, especially the cultural heritage departments, that are suffering the most. Especially in the South they are continually at risk of closure, and this is unacceptable in a country that could make enormous wealth from its cultural heritage.”

Before leaving the square we stop to listen to the speeches from the stage and do a brief round of interviews among the organizers. Leonardo Bison, from the collective Do you recognize me? I am a cultural heritage professional is among those who worked hardest to make the event a success. He is in Rome with members of his group and is very pleased with how the day is progressing. “It’s exciting,” he tells us, “it’s an event that only three or four years ago would have been absolutely impractical, unthinkable, with buses arriving full from all over Italy, with people deciding to leave the night before from Sardinia, from Sicily. It’s an incredible thing, and hopefully it’s the first of a long series ... or it’s the last if the government decides to do what it has to do. I don’t know if the latter will be the scenario we have to expect: if it is, we will still be here to assert our rights, and there will be a lot more of us.” Isabella Ruggiero, president of the Association of Licensed Tourist Guides, on the other hand, describes the difficulties of her profession: “We are also participating to ask the government to intervene effectively and decisively on some issues that impact our work so much and are taking away jobs. First there is the problem of the progressive privatization of public monuments, in the sense that the concession of services in public monuments is unfortunately being managed in a way that becomes almost privatistic, against any competition law. And then there is the problem of volunteerism, which, used indiscriminately in the field of cultural heritage, goes to take away work from all figures, including that of guides.” Emanuela Bizi, National Secretary of SLC-CGIL, took the stage with a particularly harsh intervention: “this country has never thought of culture as the skeleton that holds it up, and has always given a damn about the conditions it demands of workers in this sector. Entertainment workers have no rights: it’s time to end it. Citizens are experiencing a cultural regression, culture is being lost, and this situation gives rise to internecine wars between citizens, and if you come to think that an immigrant crossing the sea, or a woman who has suffered violence, can represent competitors in the labor market, it means that you no longer know how to reason. Parliament must recognize rights for all: no more free labor.” Silvia Ruffo, an opera singer with the Arena di Verona Chorus, speaks on behalf of the Opera and Symphony Foundations Committee, “We are a pluralistic group, we have different political preferences and union affiliations. But all together we wanted this demonstration to claim our professional dignity, the civil and social vocation that our theaters should have. For more than two decades we have been suffering punitive laws by governments of all colors, aimed at the dismantling of the public cultural heritage highlighted by the risk of downgrading of the lyric-symphonic foundations, with the infamous Article 24 of Law 160, passed by the previous government. They wanted to attribute the problem of the crisis of the opera foundations to the fixed costs of employees, while the then main reason for economic instability was determined by inadequate investments. One example for all: the Arena di Verona. An entire corps de ballet laid off without redeployment, the philharmonic theater closed for two months of the year for three consecutive years, with orchestra, chorus, technicians, administrative staff at home without pay. In the summer opera festival hundreds of historical precarious workers with hiccup contracts, with the erosion of their rights and the stupendous curtailed. We appeal today to the institutions and Minister Bonisoli to finally demand a change from the cultural policies adopted so far. Our cultural heritage is an asset of all, which generates wealth not only in the individual and society, but also in the economy, going to contribute, at the rate of 7 percent of GDP, two billion euros a year.”

|

| Moments of the event for culture on Oct. 6 |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

|

| Moments of the demonstration for culture on Oct. 6 |

After all, among the demonstrators, who were called together for a moment of confrontation on the problems of the culture professions, there is an awareness that demonstrating to demand more culture is equivalent to demonstrating for the common good: more investment in the sector translates into economic returns of all interest. The Symbola Foundation has calculated that the Italian cultural sector, in 2016, produced nearly 90 billion euros, with a multiplier effect on the economy of 1.8: meaning that for every euro invested in culture, there is a 1.8 return in other sectors. Consequently, the nearly 90 billion activates another 160 billion, for a total of 250 billion euros, which corresponds to 16.7 percent of national value added. The challenge that awaits culture in the future is therefore twofold: on the one hand it concerns the intangible value of culture itself, and on the other its economic value. “We have a duty to look ahead,” stresses Federico Trastulli of the UILPA-BACT union, “and prepare the ground on which the near future can blossom without falling into communication traps and avoiding sectoral logics. The constitutional dictate of Article 9, for those who believe in it, is the beacon of our progress and demonstrates, both because of the socio-political temperament we are experiencing and because of the bulletins involving our extraordinary heritage, that there is room for everyone and a need for all professionals in culture, which is a bulwark of democracy, an essential public service, a social elevator, food for the spirit, an instrument of civilization, a place of claim and identity memory.” The October 6 square, according to Trastulli, gave rise to a “small miracle”: “cultural professionals from different sectors, public and private, contracted and precarious who meet without the presumption of being one more important than the other, but with the conviction, at least this I believe, of being from tomorrow stronger than each other because united by an awareness, that the cultural sector is in spite of everything extraordinarily vital.”

And so that Piazza Mastai does not remain just a postcard, several proposals emerged from the event. Trastulli himself launches the idea of an atlas of the professions of culture, which should lead to the birth of a statute for cultural workers, so that the workers themselves will be more covered by rights and guarantees. Tour guides propose a reform of the current national licensing system, audiovisual workers wish to commit to the drafting of a national contract for their sector, and all others propose that if national contracts are not respected, mechanisms should be activated that would result in the forfeiture of funding. Still, a proposal emerges from the square for a restructuring of MiBACT, which would cancel the Franceschini reform and be able to put superintendence and museum workers in a position to carry out their activities without overlapping competencies. The need for a law that decisively and as drastically as possible combats volunteering in the cultural heritage is then reiterated, setting stakes not to be crossed so that volunteering does not become a substitute for work. As for the opera and symphony foundations, the square proposes to review the system of allocating public grants, which is considered inadequate and a source of many problems. Then there is the desire to ensure that Italy gets to invest sums equal to 1.5 percent of GDP in culture (we are currently stuck at 0.7 percent instead). What all the protesters are convinced of is that it is not true that nothing can be done to improve the fortunes of the sector. And that October 6 marked a point of no return: from now on, cultural workers are convinced that the sector will have to move united, to respond adequately to the challenges that the future will present. And the eventual victories will not be victories of individuals, or of the sector alone: they will be victories that will serve the whole country.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati

Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da

Federico Giannini e

Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato

Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009.

Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamo

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.