Serendipity, the British would say. It is the word they use to refer to those totally unexpected discoveries, exceeding expectations, that come when you were looking for something else. It is more than a fortuitous finding: it is a surprising outcome that no one expected and that came while one was scrambling for a lesser result. It is the amazing result that comes by chance when plans of a completely different kind had been made. Serendipity: the term had been invented by Horace Walpole in the late eighteenth century, thinking of a fourteenth-century Persian fable about the three sons of the king of Serendip, the ancient name of present-day Sri Lanka, who were sent by their father to learn about the world and returned home after making astonishing and totally unexpected discoveries. One could then speak of serendipity also for the 15th-century fresco that was discovered a year ago in Rome, on the site of Palazzo Nardini, which since July 2023 has undergone major conservation restoration work, entrusted to Antonio Forcellino, under the direction of Marina Cristiani and Isabella Diotallevi. A restoration to recover and put to new use one of the most significant Renaissance palaces in Rome’s historic center, on Via del Governo Vecchio, two side streets after Piazza Navona.

Antonio Forcellino, he tells us, was looking for something quite different: he had proposed to the property to do a recovery of the nineteenth-century plasterwork, which he imagined he would find under the plasterwork of the great hall on the first floor of Palazzo Nardini. Today that hall is an enclosed room, but in the 15th century it was an open loggia that served as an atrium: the entrance to the building, the restorer explains, at that time gave onto what is now Via di Parione, where one can see a facade that still has many elements in common with that of Palazzo Nardini. Then, in 1541, the part of the loggia open to Via di Parione suffered a collapse, the room was closed, buttresses were added, and the painted walls, or what was left of them, were obliterated, since those frescoes from seventy years earlier or so no longer responded to current taste. Not even a hundred years old and already the memory of those paintings had been lost, so much so that sixteenth-century sources, Vasari in the lead, make no mention of the frescoes in Palazzo Nardini. But it is likely that the memory of those paintings was even more short-lived: exactly fifty years, from 1477, the year the building was finished, to 1527, the year of the sack of Rome, a traumatic event for Palazzo Nardini as well, which was occupied by the Lansquenets, sacked, devastated. There is also their graffiti, on the resurfaced fresco. Writings, scribbles, coats of arms, symbols. There is even what appears to be the mask of a krampus, a sign of the unmistakable origin of the occupants.

“We found this fresco while we were looking for plasterwork,” Forcellino explains. “We weren’t looking for anything else, since this building had already undergone restoration, so we didn’t expect to find this fresco. We found it by accident, when we found a fragment, a hint of a figure, a face under the surface: we then realized that there had to be something bigger, and from there the adventure of this fresco began, which is extraordinary in many ways: because it is rare, because it is a masterpiece, because on the surface it also bears the date 1477, so we are sure it is coeval with the construction of the palace.” The date 1477 is amid the inscriptions left by the Lansquenets, which are also, now, being examined by scholars. At the time of the sack of Rome, the palace was the seat of a college desired by the man who had the building constructed, Cardinal Stefano Nardini, born in 1420, who came from a noble family of Forlì, a singular character who in his youth was a condottiere in the service of Antonio I Ordelaffi and Francesco Sforza, and then, having laid down his swords, was first a jurist and then a cleric, becoming in 1451 a chamber cleric at the time of the pontificate of Nicholas V, and already the following year an apostolic nuncio to France. His cursus honorum was rapid: in 1458 he was apostolic nuncio to Germany, in 1461 he became archbishop of Milan, from 1462 to 1463 he was papal governor of Rome, in 1465 commissioner of the apostolic treasury, the following year again nuncio to France. On his return to Rome for the conclave of 1471, he was among the principal supporters of Francesco della Rovere, later elected pope under the name of Sixtus IV. The services he rendered to the new pontiff earned him, in 1473, the appointment as cardinal, the obtaining of various rich commissions and the possibility of starting the construction of his magnificent palace, the result of the arrangement of several properties that Nardini had acquired along the via Papalis, today’s via del Governo Vecchio, at that time one of the main arteries of central Rome. We know that in 1480 Cardinal Nardini must have already lived in the palace, since the donation inter vivos to the confraternity of the Most Holy Savior ad Sancta Sanctorum dates back to June 4 of that year, so that after his departure, in the rooms of the’building would be founded a college intended to house, in cycles of seven years, twenty-four young men from good families but of meager means, so that they might be initiated into the priesthood and study by taking courses at the Studium Urbis, that is, the University of Rome. Nardini then also left to the college his entire library, of which, however, nothing remained.

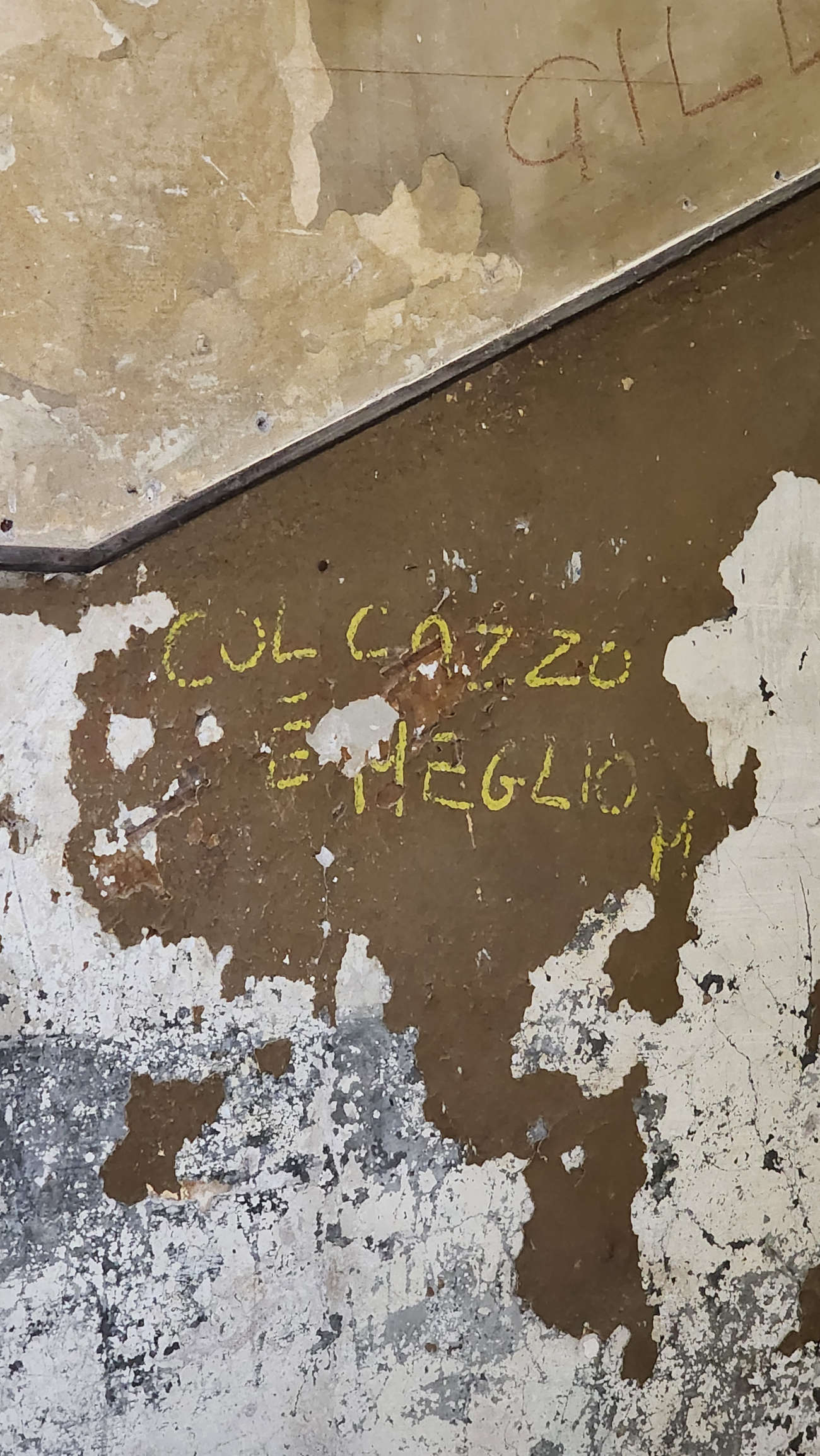

It is therefore at the time of the Nardini College that the upheaval in the layout of the building dates back, which remained the property of the Brotherhood of the Savior until 1624, when, through the strong interest of Pope Urban VIII, it was ceded to the Apostolic Chamber and made the seat of the Governorate of Rome, which remained in Palazzo Nardini until 1755, when Benedict XIV decided to move it to Palazzo Madama (following that event the street took its present name of “via del Governo vecchio”). In 1870, after the annexation of Rome to the Kingdom of Italy and following its elevation to the capital, the building became the seat of the Magistrate’s Court: a plaque on the facade still recalls this function. It then became the seat of the Vittoria Colonna Female Educatory, housed an air-raid shelter during World War II, and then, starting in 1957, when the building of the new judicial city at Piazzale Clodio began, Palazzo Nardini was abandoned. Its last period of life was in the years between 1976 and 1984, when it was occupied by the Women’s Liberation Movement, which made it the headquarters of the International House of Women: entering the building site one can still see the graffiti of that time, the writing on the walls, scraps of posters. When that experience ended with the eviction of the occupants, Palazzo Nardini fell definitively into a state of abandonment from which it seemed destined to rise again in the early 2000s, when the building was purchased by the Lazio Region and underwent an initial restoration that led to the discovery of important fifteenth-century frescoes on the main floor, which will be discussed in more detail below. At the time, the region was governed by the Marrazzo junta: subsequent political changes led to the suspension of the restoration work, and as a result of further administrative vicissitudes, which can be glossed over, the palace was put on the market and purchased by the current owner, who intends to bring it back to life. And it is for this reason that, in 2023, the current restoration began.

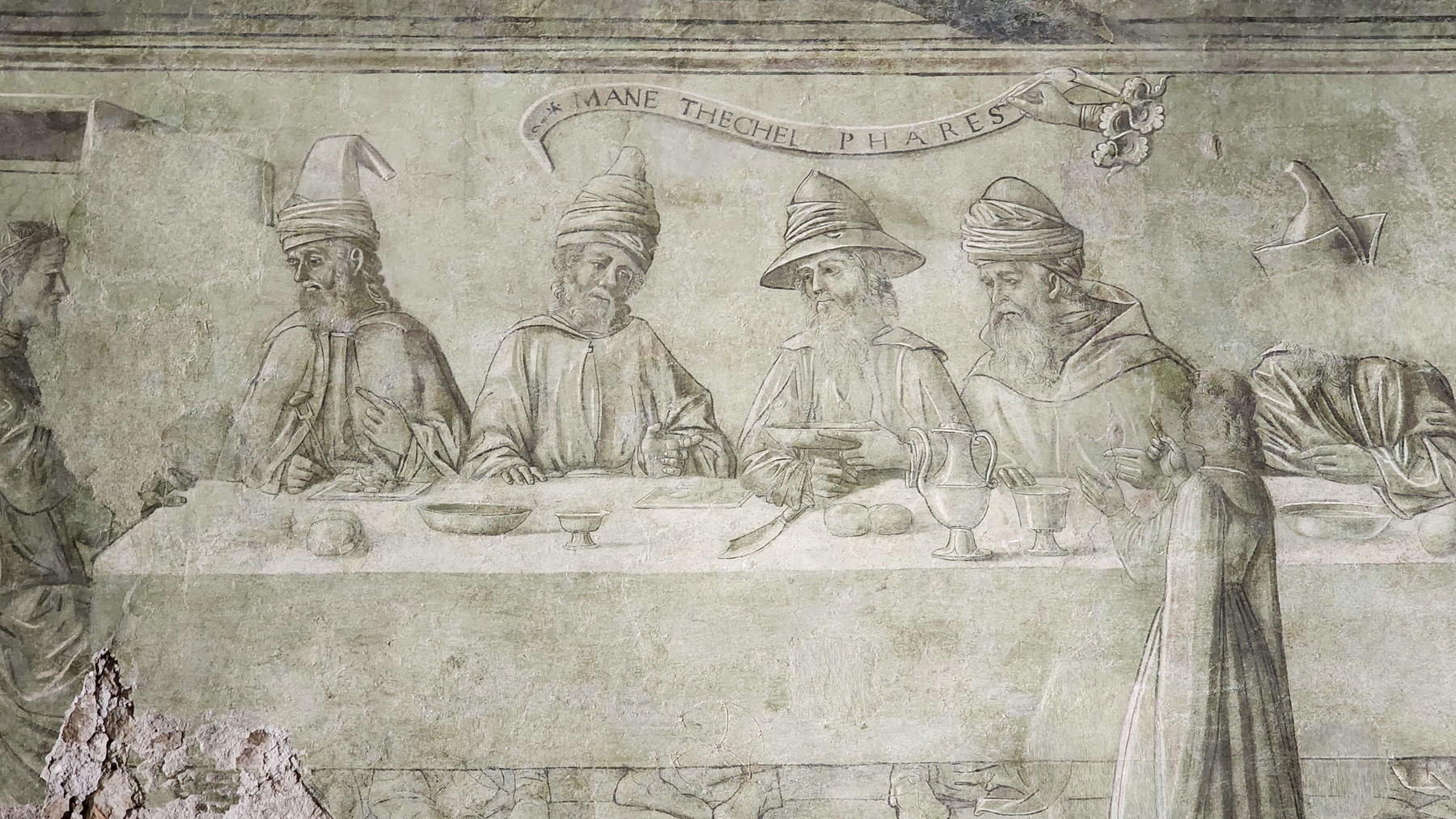

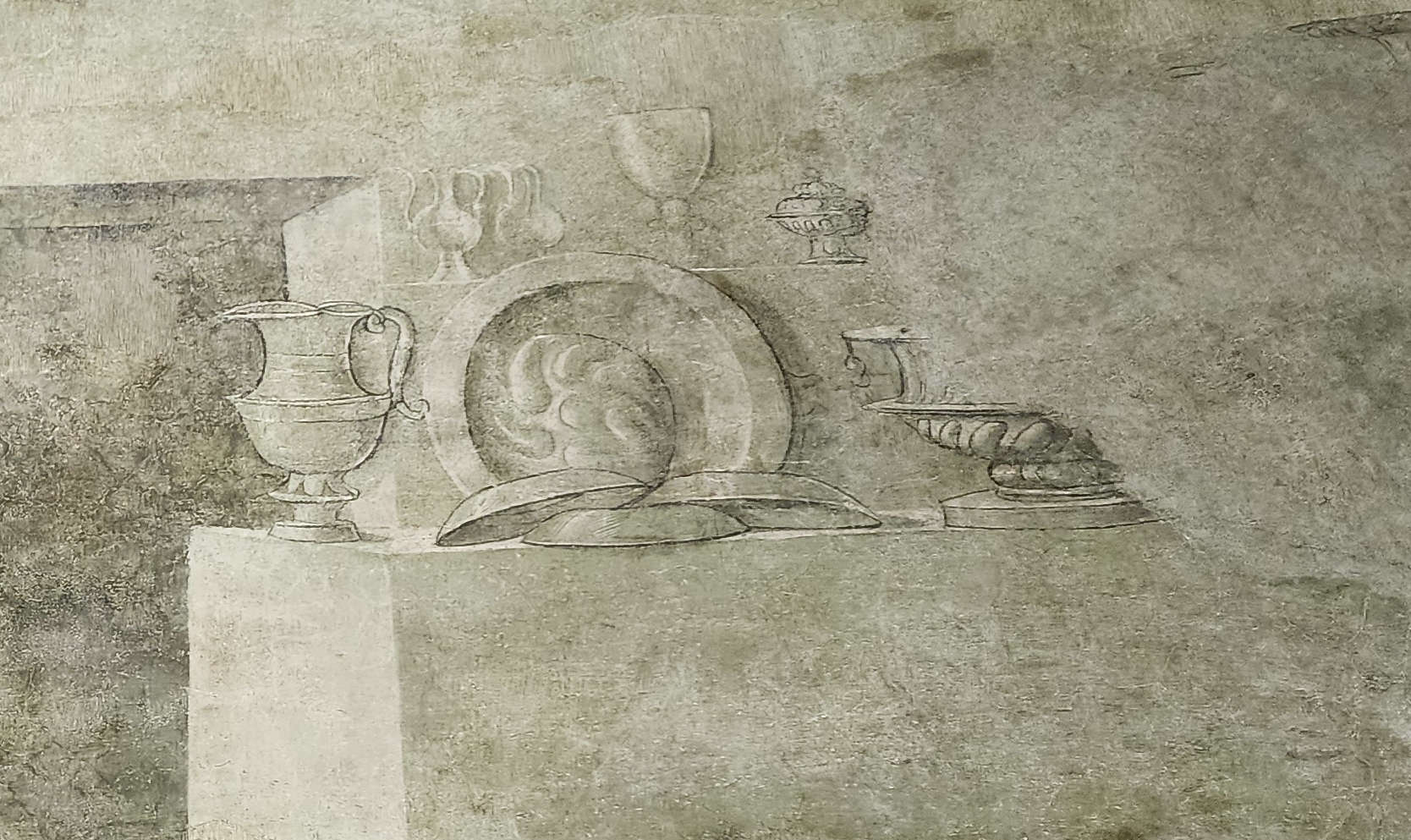

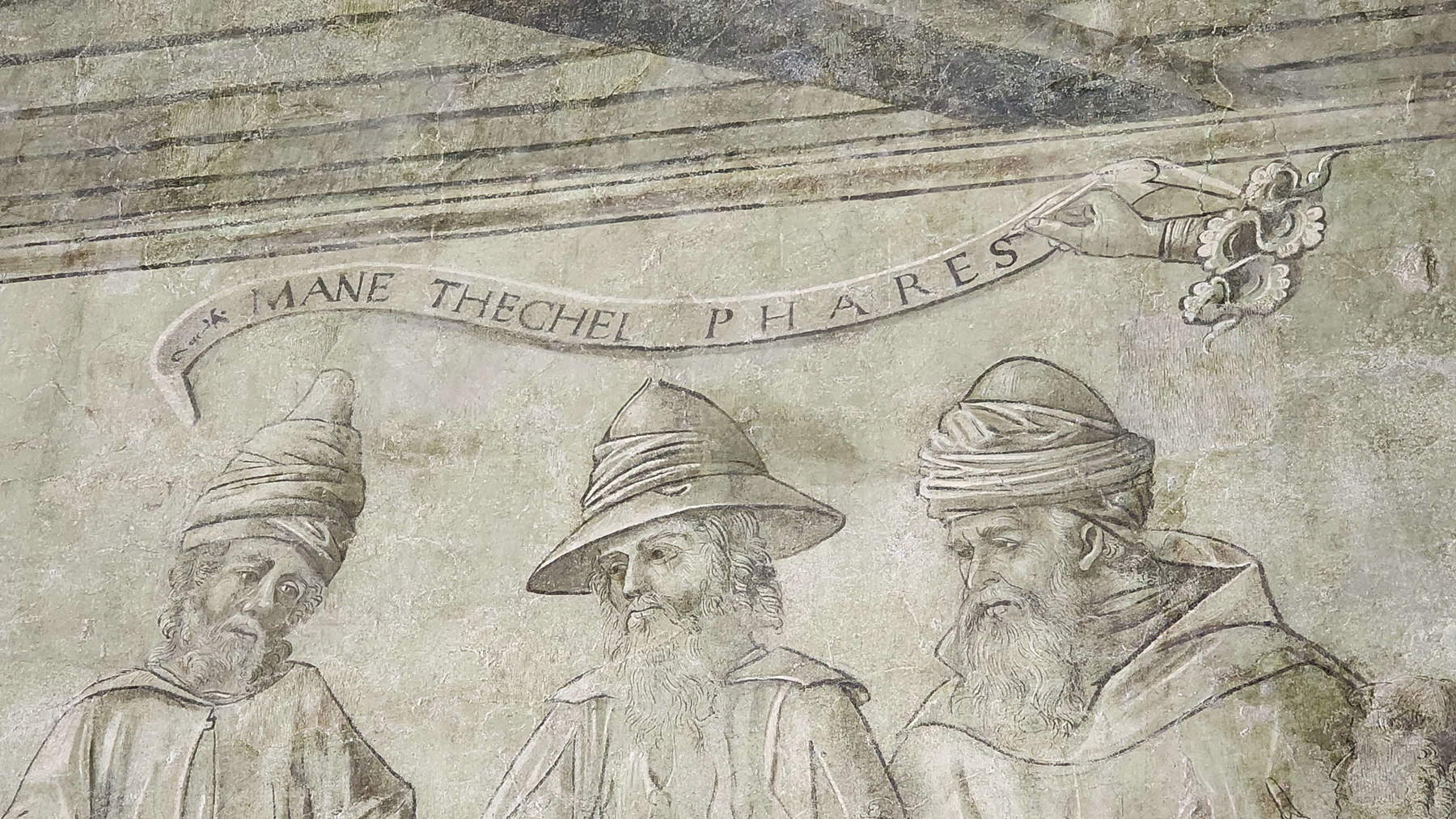

The newly rediscovered fresco is the only surviving fragment of the loggia’s ancient decoration: nothing else has been found under the glaze, but this single scene alone is enough to restore to Rome one of the most important pages of its fifteenth century, already this fresco is enough to give an account of Cardinal Nardini’s taste, refinement and updating. The scene depicts several figures seated around a laid table, wearing headdresses of the most bizarre fashions. In front, some attendants are making sure that everything is going well, and in the center of the room, depicted with clever perspective acumen, hangs a scroll with the inscription “Mane Thechel Phares,” a motto in Aramaic that allows the scene to be identified as the biblical account of the banquet of Balthazar, an episode narrated in the book of the prophet Daniel. Balthazar, son of Nebuchadnezzar, is the last king of Babylon, and he is locked in his palace when the capital of his kingdom is besieged by the army of Darius, king of the Medes and Persians: nevertheless, he decides to organize a lavish banquet, ordering that the sacred vessels that his father had taken away from the temple in Jerusalem after occupying the city be brought to the table. In the fresco, Balthazar is the figure in the center of the table, wearing a turban, caught as he raises the index finger of his left hand to give his servants the order to bring the trays of food to the table: it is precisely those plates and trays that are the objects on which Balthasar is performing the sacrilege, and it is for this reason that the artist insists with a certain zeal on the tableware, even to the point of performing a very modern still-life piece on the right side of the fresco, with the vases that also seem to reflect the light as a result of the skilful highlights, some of which have survived, that give relief to the objects. The book of Daniel recounts that suddenly, while Balthasar and his court were engaged in their merrymaking, a hand appeared on a wall in the room, tracing an enigmatic and disturbing inscription, “Mane, Thechel, Phares.” The king, terrified by the apparition, ordered the soothsayers and astrologers to be summoned, and promised, to whoever first succeeded in deciphering the writing, a purple dress, a gold necklace, and the third highest office in the government of the kingdom. No one was successful in the undertaking: the only one who gave the king an explanation was Daniel, who had been deported to Babylon along with other Jews by Nebuchadnezzar. The prophet explained to Balthasar that the hand he had seen was that of God, who had come after his sacrilege to write what was, in fact, a sentence for his kingdom: "Mane: God has counted your kingdom and put an end to it; Thechel: you have been weighed in the scales and have been found insufficient; Phares: your kingdom has been divided and given to the Medes and Persians.“ The three words can thus be translated as ”Counted, Weighed, Divided." That same night, Balthazar would be killed by the Chaldeans.

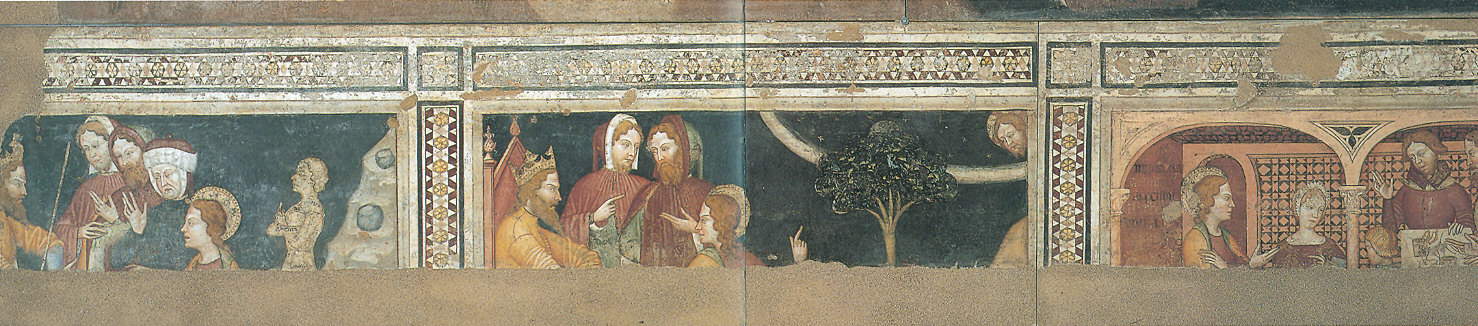

Balthazar’s banquet is a fairly frequent theme in paintings of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries (famous are the paintings by Tintoretto and Rembrandt, the former preserved in the Castelvecchio Museum in Verona and the latter in the National Gallery in London), but its attestation at the time of the fresco in Palazzo Nardini is rare: perhaps the best-known example is the fragments of a cycle of late 14th-century frescoes, ascribed to the Master of St. Catherine, that decorated the church of San Lorenzo in Piacenza in ancient times and are now in the Civic Museums of Palazzo Farnese. In one of the frescoes illustrating episodes from the life of Daniel, a fragment of the moment of Balthasar’s banquet survives in which Daniel is seen being presented to the king to decipher the writing. There are then some examples in the miniatures: a depiction of the banquet is found, for example, in Rudolf von Ems’s chronicle of 1400-1410, preserved at the Getty Museum, while even older (from 1220) is the commentary on the book of Daniel by the Spanish monk Blessed of Liébana, preserved at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, in which still the prophet is depicted pointing to the inscription “Mane Thecel Phares” to offer his explanation to Balthazar. The special feature of the commentary scene, besides the fact that the banquet participants are reclining on triclinia, is the inscriptions commenting on each element of the scene. In fifteenth-century painting, however, Old Testament themes are very rare. And then there is the more immediate precedent, the Bible of Edward IV, preserved in the British Museum: here, too, the diners wear hats in the strange fashions we find in the Palazzo Nardini fresco.

It remains to be seen who is the author of this scene. It is executed in monochrome, the figures outlined on a green surface, reminiscent of the paper on which artists in Renaissance workshops traced their drawings. The choice of monochrome, which is quite distinctive, according to Forcellino is due to... reasons of image: the home of a cardinal had to inspire sobriety, moderation. Especially since that was the entrance to Cardinal Nardini’s residence. A loggia frescoed with colors would have been indicated for a prince, would have conveyed an image of exaggerated luxury for a prelate. “For the cardinal it was appropriate instead to maintain a more pauperistic tone, we would say today,” Forcellino adds. According to the restorer, it is pretty much taken for granted that the fresco should be dated to 1477, although at the moment we are still in the study phase: the graffito with the date is important to place the fresco, but research on the materials and especially research in the archives are still ongoing, because to date no document has yet been found that can ascertain the name of the painter. Perhaps an engagement document attesting to the commission, a note of payment, something like that. For now, beyond documents related to the palace, such as the deed of gift to the Confraternity of the Savior and the cardinal’s will, nothing has been found that could be related to the frescoes that decorated the loggia.

The painter worked with a unique technique: on a preparatory base consisting of green earth, the artist spread a few pigments to achieve the effect of a large, lumed drawing, with the shadows and halftones defined only by a few purple glazes, and the depth accentuated by the highlights. “It’s an extraordinary technique because on a fresco base there are white lime highlights and halftones that look almost like a lacquer,” says the restorer, who also notes a further peculiarity: the artist did not bring back the drawing from a preparatory cartoon. “He had done it freehand, like a drawing on a large sheet, because there are several adjustments: for example, in the clothes, at the height of the heel. However, in spite of that, the artist shows extraordinary confidence. And then, the quality of the fresco, the liveliness of the figures, the precision of the perspectives show that we are dealing with an important piece.” According to Forcellino, the most likely name at the moment would have to be Perugino. If it is not Perugino, one can imagine the name of an artist close to him, or who had at least in common his cultural background. The Umbrian painter in 1479 is attested in Rome, and the year before, in Cerqueto, he had painted a St. Sebastian that, in Forcellino’s opinion, can be compared to the figures in Palazzo Nardini especially in the way the images are constructed and in the type of highlights: “It is a Perugino still Verrocchioesque, and these highlights are really a writing. One can copy an image, but the way of writing the highlights, the way of constructing the figures with small brushstrokes, all this should be read as a drawing, like one of those drawings on green paper that were made in Verrocchio’s workshop.”

Another name to be considered could be that of Melozzo da Forlì, who had already been juxtaposed to the frescoes found on the piano nobile (in the rooms whose height has been greatly reduced by subsequent renovations), extensively illustrated in 2018 by Stefano Petrocchi, then director of the Polo Museale del Lazio, during a conference dedicated precisely to Palazzo Nardini. “A moment in the history of the great Roman Renaissance of the 1970s that is composed and unveiled in Palazzo Nardini”: this is how Petrocchi had defined those frescoes. There is, meanwhile, a frieze, at the center of which appears the cardinal’s coat of arms, the same one that later also decorates the portal on the facade of Via del Governo vecchio. The coat of arms constitutes an inescapable terminus post quem, since Stefano Nardini became cardinal in 1473: the frescoes, therefore, cannot precede this date. The frieze, typical of the Rome of the 1470s, for Petrocchi can be traced back to Melozzo da Forlì, a protagonist of Roman painting of the time together with Antoniazzo Romano: both were protagonists of a classicist revival that, in the great Roman palaces of the Renaissance, included this type of frieze decoration.

The curious fact is that under the frieze a scene has been discovered that appears stylistically far removed from the decoration above it. The fragments appear barely legible, but some inscriptions found already during the first restorations in the 2000s made it possible to identify the scenes as what remains of episodes that were also Old Testament, taken from the book of Samuel. Petrocchi had already published these scenes in the Bollettino Telematico dell’Arte, in a 2006 article, in which he attributed the images to a Nordic artist, perhaps German, a certain Petrus, active between the 1460s and 1580s in Subiaco (the Last Judgment dated 1466 that can be seen in the Benedictine abbey of Subiaco is due to him). He is an artist linked to a markedly late Gothic figuration, which has nothing to do with the frieze that dominates the figures from above, nor with the scene uncovered in the loggia, although it is always episodes from the Old Testament.

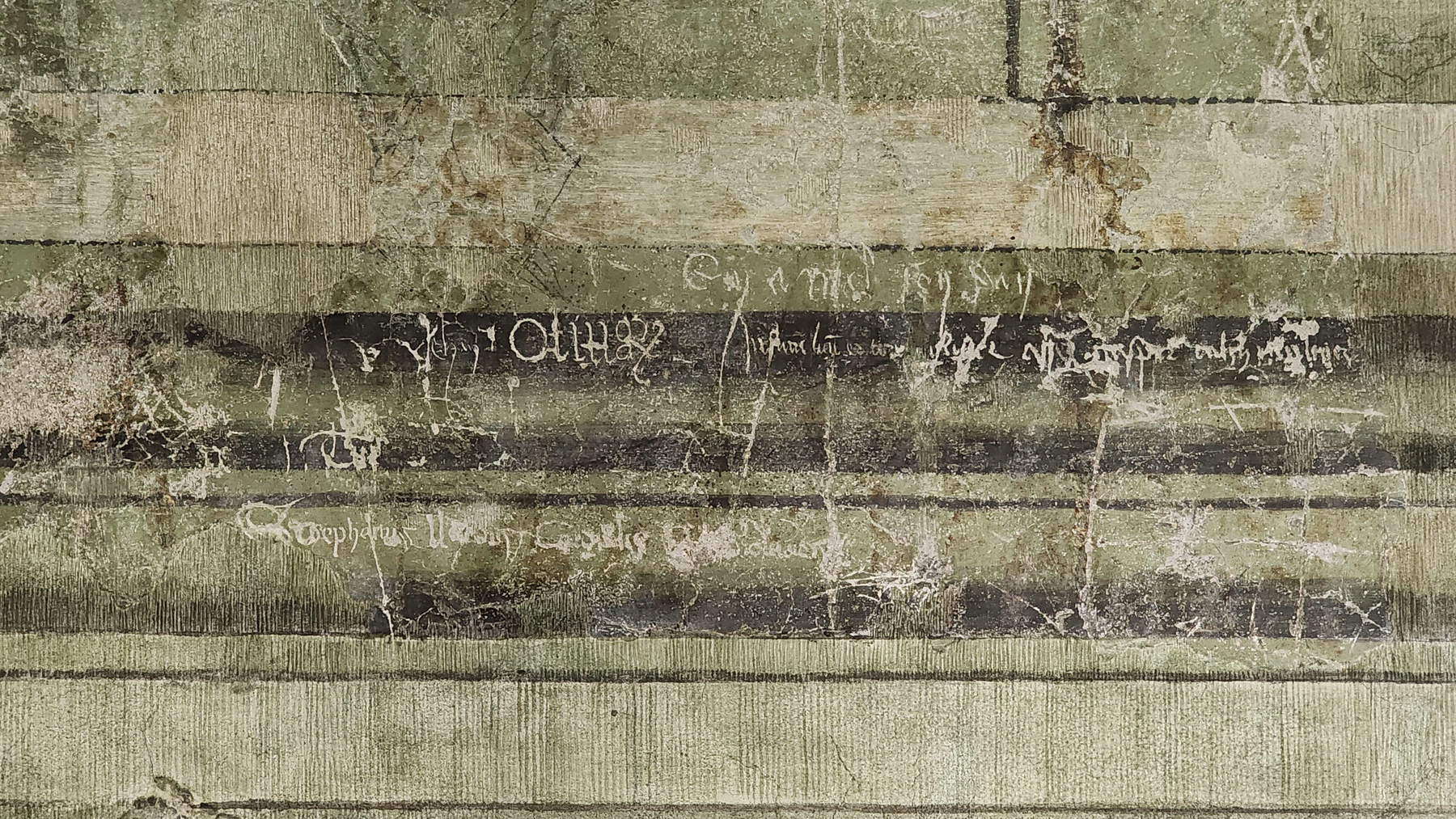

We can rule out the possibility that these scenes are the result of an earlier decoration and then incorporated into the palace at the time of its rearrangement, although even older pieces of painting have been preserved. The most recent discovery relates precisely to a decorative fragment from the medieval period. The fresco with the Banquet of Balthazar resurfaced in early 2024, while dating back to recent weeks is the discovery of a unique painting that imitates a wall face, and for which one can hypothesize that it is what remains of a decoration that preceded the work on Palazzo Nardini, which, as mentioned in the opening, is the result of the incorporation of several properties. One of these properties was owned by a certain Bartolomeo da Novara, who owned two houses in the area, both with towers: the facing was found in a part of the ancient outer tower of the house, incorporated by Nardini at the time of the work on the palace. It is a rough plaster, on which ancient decorators in the Middle Ages spread only a little color and added marks to simulate bricks. The result is a faux ashlar, with very simply painted ashlars. A small portion of it has been preserved, but it is still a relevant testimony. “So,” Forcellino explains, “we have here the oldest known faux stone facing in Rome. It was saved, we don’t know why and we don’t know how, but it was saved.”

On the “magister Petrus” scenes, however, other conjectures can be made. The manners this painter demonstrates between the 1470s and 1580s (his last attested work is from 1483) are entirely compatible with the scenes in Palazzo Nardini: Thus, it cannot be ruled out that the Palazzo Nardini scenes belong to a cycle commissioned by Nardini himself, who, according to Petrocchi, may have known magister Petrus in different ways (perhaps he met him in Germany at the time when Nardini held in the area the post of protonotary apostolic, perhaps he simply got to know him by virtue of the fame Petrus had obtained as a result of the Subiaco exploits, where the German artist obtained what Petrocchi calls a “decorative monopoly”). Then, for some reason, the cardinal had to veer toward more avant-garde artists, so to speak: both the frieze and the scene of Balthasar’s boarding school in the loggia could be explained in this way. What is certain is that too little survives to allow well-founded hypotheses about the decorative enterprise of the palace, about the contents of its iconographic program (the fact, however, that all the frescoes are related to the Old Testament could be an indication of a single design). One can make just a guess about the scene of Balthazar’s banquet: at the time, the problem of the Turkish threat was particularly felt, so much so that Pius II, in 1464, had placed himself at the head of a crusade that, in his intentions, was supposed to curb the advance of the Ottomans (the project failed because the pontiff died in Ancona shortly before leaving). Stefano Nardini had been among the advisers who helped him organize the expedition, and although several years had passed since that event, it is likely that the cardinal still wanted to establish a comparison between the Babylonian destroyers of the Temple of Jerusalem and the Turks who threatened Christendom at that time.

The restoration site is now entering its final stages. Work is scheduled to be completed in July of this year. Those who visit the palace will be able to see a philologically recovered building, with the rooms covered with paints made directly on the construction site, without restorations in style but at the same time without interventions that would distort the structure and history of the palace. Already, anyone passing by via del Governo vecchio can see the facade and portal cleaned of dirt and red paint added in the 19th century. The opening is scheduled for the end of the year: theasset manager of the group that owns Palazzo Nardini, Andrea Mei, said in January in an interview with Repubblica: “We approached this restitution of beauty with respect and a great sense of responsibility. When the work is completed, certainly by 2025, Palazzo Nardini and its treasures will finally be available to the city and the Romans.” All that remains is to wait.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.