July 4 marksAlice Day, an anniversary that commemorates the afternoon in 1862 when Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, destined to become known by the pseudonym Lewis Carroll (Daresbury, 1832 - Guildford, 1898), first told the story of a little girl named Alice during a boat trip on the Thames with the Liddell sisters. Among the listeners was Alice Liddell, to whom the story was dedicated. The improvised tale would become, three years later, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, one of the most influential novels of thenineteenth century, destined, almost a century later, to inspire even Disney’s animated version, which in 1951 would make Carroll’s imagined world even more visible, and alienating.

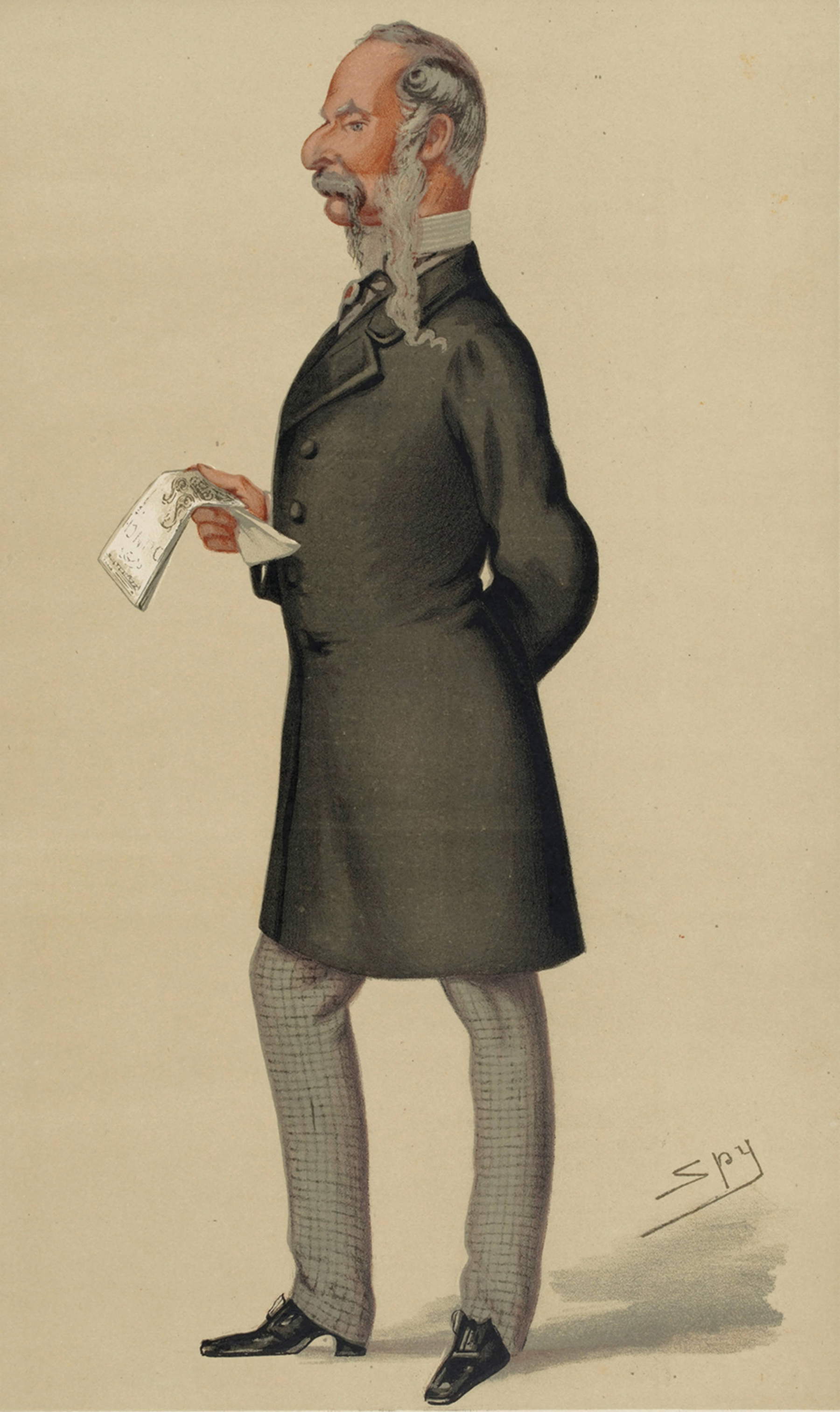

But what is the story behind the novel’s illustrations? Initially, the author tried to illustrate Alice’s manuscript himself (link to his illustrations here), but he soon realized that more was needed for publication. A more confident stroke, capable of holding up the ambition of the text, was needed. The choice fell on John Tenniel (London, 1820 - 1914), a leading artist for Punch (a British satirical magazine) and an already established figure in Victorian illustrated satire.

Tenniel took his first steps in the art world by training at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, where he practiced copying classical sculptures, illustrations from heraldry books and costumes, and scenes from live performances. The son of a dancing and fencing master, he developed a natural aptitude for depicting movement, but his real strength lay in his prodigious visual memory, which enabled him to reproduce familiar faces and deform them with satirical precision. He loved to draw by directly observing reality and drew particular inspiration from the theatrical gestures of actors, an element that shines through in many of his works. His interest in the stage is shown, for example, in a drawing depicting a performance of the opera Maritana, staged at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane in November 1845.

His precise, sharp drawing imbued with irony thus seemed perfect for illustrating Carroll’s manuscript, yet the invitation was not accepted with immediate enthusiasm. Tenniel hesitated. But why? Certainly, the world of Alice intrigued him, but the very absence of a traditional narrative structure alarmed him. The author’s story overturned every logical principle and eluded any stable representation.

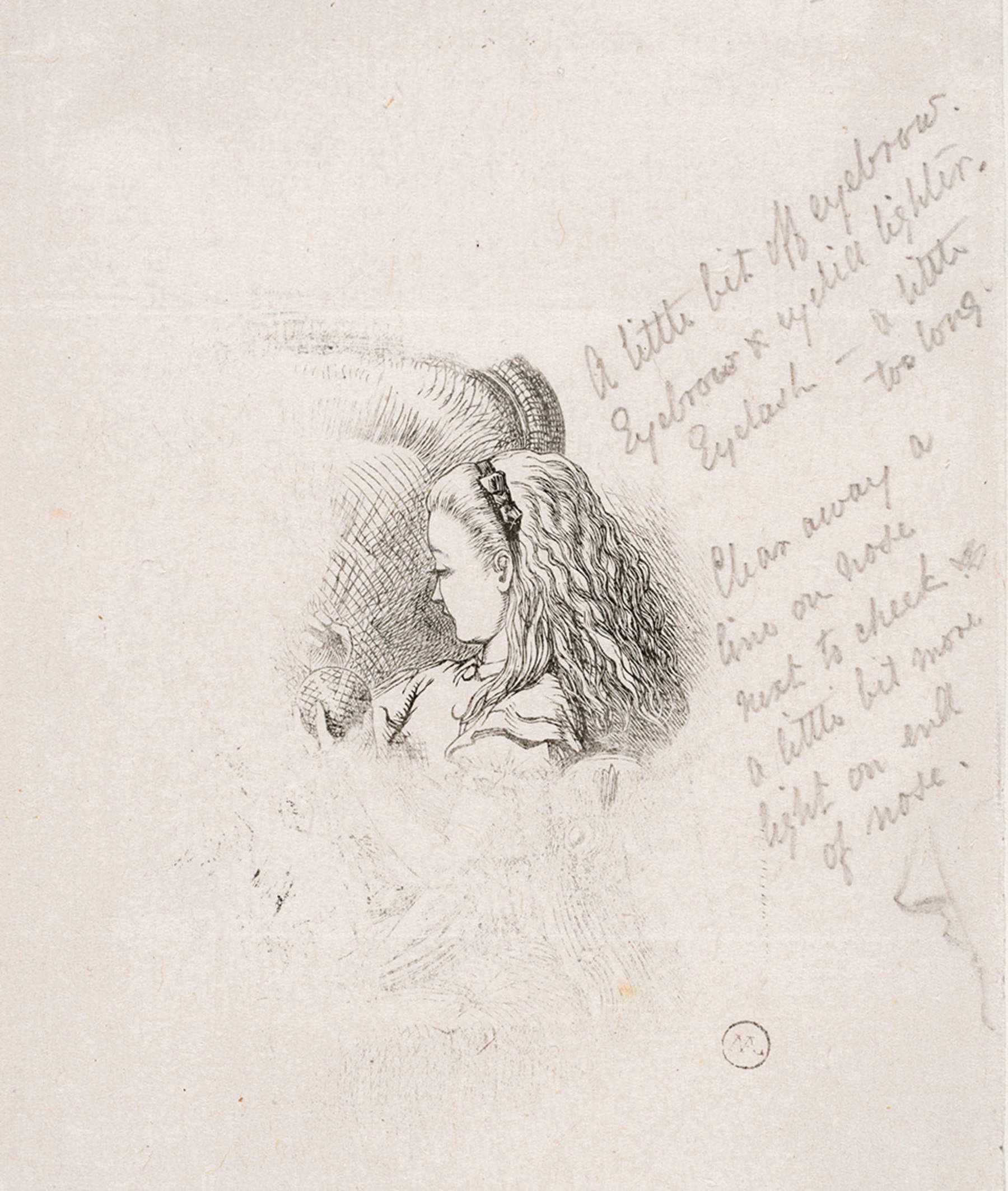

Nevertheless, the collaboration between Carroll and Tenniel took shape, and it was not without scruples and painstaking revisions. The author and illustrator shared an obsessive attention to detail. One of the proofs drawn for Through the Looking Glass, now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, bears some of Tenniel’s autograph remarks, “Slightly misaligned eyebrows. Lighten stroke on eyebrow and eyelid. Eyelashes appear excessively long. Eliminate a line between nose and cheek. Add a hint of light at the tip of the nose.” The proportions, lights, micro-expressions, and strokes were indeed meant to restore the ambiguity and strangeness of the text. Thus, it is hard to imagine the effectiveness of Alice, both in written form and in the Disney adaptation, without Tenniel’s intervention. His graphic interpretation, between the grotesque and the realistic, fixed faces and gestures that still remain etched in the memory of generations. And those very features, refined and paradoxical at the same time, served as a reference for Disney artists, who translated the 19th-century plates into animated images, saturating them with color and projecting them into surreal landscapes.

Either way, the result of the illustrations was surprising. Tenniel created the visual aspect, developing a gallery of figures that would become an integral part of Anglo-Saxon figurative culture. A few examples? The White Rabbit with the vest and watch, the Hatter with the hat marked “10/6,” or even the Queen of Hearts with the menacing grin, all characters that still populate the symbolic baggage of millions of readers today.

Tenniel’s plates, strictly in black and white, were engraved on wooden blocks by skilled artisans, according to the publishing practice of the time. But the artisanal technique did not limit invention: on the contrary, it forced it toward synthetic, essential solutions that are still striking for their expressive power today. Tenniel drew characters with exaggerated proportions, theatrical poses, but never caricatures. The effect was uncanny: a real child moved in a world where every rule was turned upside down, but the drawing never succumbed to disorder.

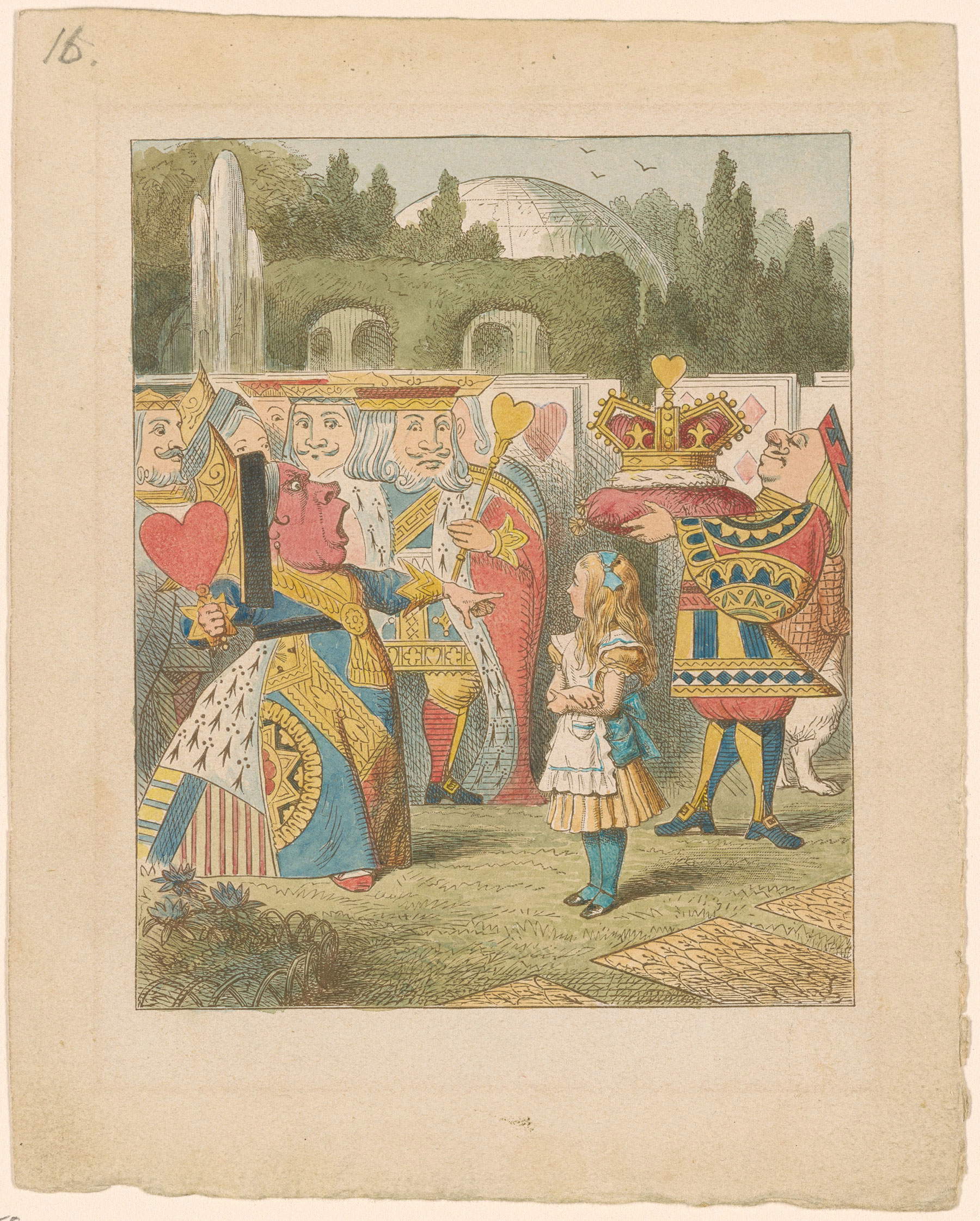

A century later, in 1951, Disney faced the challenge of adapting the novel to the language of animation. Tenniel’s mark was metabolized, transformed. The Disney-esque Alice, blond and round-faced, lost the sternness of the Victorian protagonist, but retained awe and steadfastness. The real change occurred in the landscape.

Trees, talking flowers, and hedges trimmed with paradoxical shapes come together in a decorative composition that did not aim for realism. The curvilinear foliage, spiraling trunks, and saturated, unreal colors evoke a post-modernist reinterpretation of the Arts and Crafts style, in which nature becomes an ornamental motif, a citation, a pretext for playing with form. The plant world grows according to graphic and deliberately ambiguous principles. The treatment also approaches Naif painting, and in particular the dense, hypnotic atmospheres of Henri Rousseau. As in his jungles, the vegetation here is dense, seemingly lush, but built on a compositional artifice that reveals its mental nature. There is neither naturalistic intent nor pure abstraction. Rather, there is a strange balance, where each leaf decorates rather than shadows.

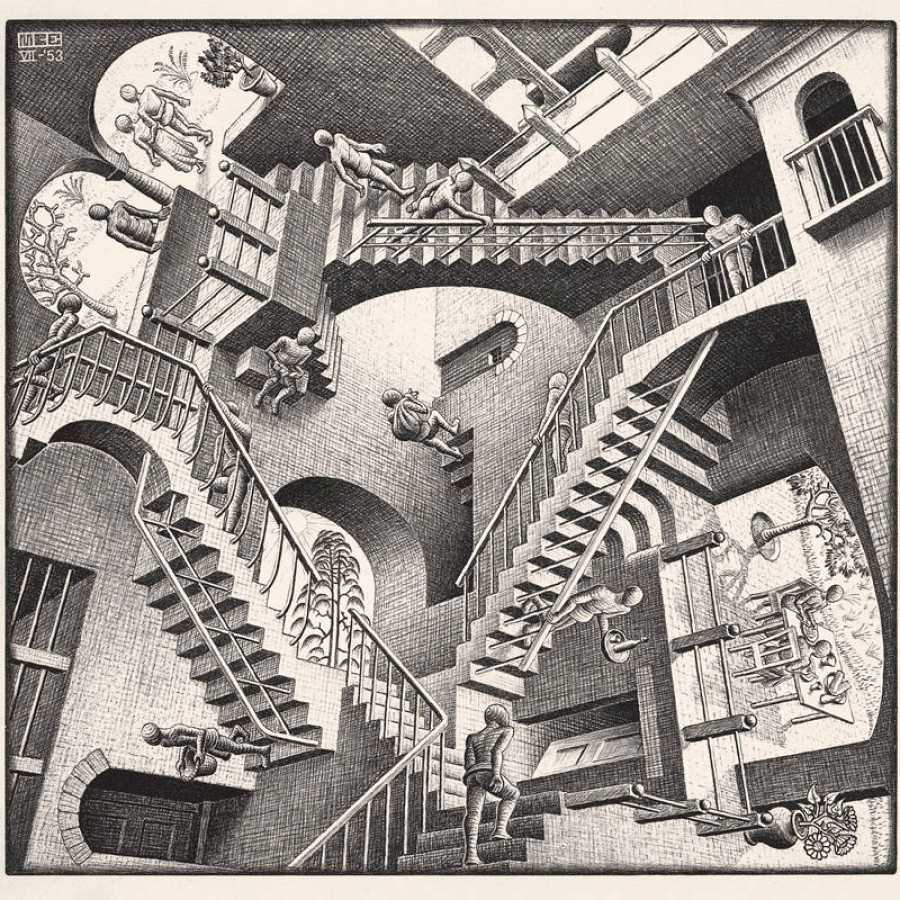

Another striking element of the Disney version is the labyrinth. In this case, the direction seems to borrow ideas from Maurits Cornelis Escher: staircases that chase each other without an end with passages that open on themselves and impossible geometries. The labyrinth is the graphic representation of absurdity, the concrete symbol of an order that has become an illusion.

The suggestions that populate Dinsey’s world, from Rousseau to Escher, show how fertile the novel was on an artistic as well as a literary level. And it all starts, once again, with Tenniel. His ability to construct a coherent graphic space, within an incoherent universe, has created a model to which every subsequent rereading must relate. It is no coincidence that many modern editions of Alice take up, update or openly quote his illustrations.

There are also not a few contemporary artists who have reinterpreted the character of Alice and her visions: from Yayoi Kusama, who transformed the protagonists into psychedelic and obsessively pointillist forms, to Dorothea Tanning, whose dreamlike figures suspended between childhood and perturbation evoked atmospheres akin to those of Wonderland. The artist’s connection with Surrealism was dazzling: in 1936 he visited the exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, describing it as “epochal.” It was there that, as he would later recount, he thought, “Damn! I can go ahead and do what I’ve always done.” Three years later she sailed to Paris with the intention of meeting the Surrealists, but the outbreak of World War II forced her to return to New York. It was precisely the conflict that brought many exiled European writers and artists to the city, allowing Tanning to approach directly the group that had so influenced her vision. Carrollian resonances can also be found in her: metamorphoses of the body, fluid spaces, transitions between rationality and dreams.

A case in point is Salvador Dalí, who in 1969 illustrated a special edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, published by Press-Random House in New York. The volume includes an etching as the frontispiece and twelve heliographies, one for each chapter, in which Carroll’s visionary universe is intertwined with the Catalan painter’s unmistakable stylistic signature: fluid colors, distorted forms and a theatricality suspended between dream and symbolism. Dali became so fascinated that he even made a bronze sculpture dedicated to the protagonist, confirming his emotional involvement with the character. It is therefore not surprising that the edition is today one of the most sought-after works by collectors, so much so that one of the few copies in circulation reaches thirteen thousand dollars.

Alice continues to be part of the contemporary world, precisely because each era can project her into its own different universe. Tenniel gave her a shape, Disney a rhythm, other artists have gone on to reinvent her in pop, gothic, psychedelic ways. But none of these visions erased the previous ones: they simply overlapped. After all, we know that in Wonderland everything is constantly transforming, without ever repeating itself.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.