It begins with a breakfast of bread, melon and wine, on August 7, 1420, the story of one of the greatest masterpieces in human history: the Dome of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, the masterpiece of Filippo Brunelleschi (Florence, 1377 - 1446), the father of the Renaissance in architecture. Indeed, in a document regarding payments, drawn up at the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore which was in charge of the work, and which is still preserved in the Archives of the Opera, we read that this was in fact the meal that, along with the pay, was offered to the workers who began work on the impressive structure: “A dì 7 daghosto lire 3 soldi 9 denari 4 per uno barile di vino vermiglio e uno fiascho di trebiano e pane e poponi per una cholezione si fe la mattina che si chominciò a murare la chupola.” It was the opening of a construction site the likes of which had never been seen before, for Brunelleschi’s feat was unprecedented, and still, in some respects, has not been surpassed: in fact, we are talking about the world’s largest masonry dome (and in Brunelleschi’s time it was the world’s largest dome in absolute terms), with an inner diameter of 45.5 meters and an outer diameter of 54.8. But not only that: the construction site of Brunelleschi’s dome presupposed a new approach toward architecture, since unprecedented problems and obstacles had to be overcome, and new machinery and new methods of organizing work had to be employed.

Discussions about the dome had begun in Florence as early as 1367, after the apsidal tribune of Santa Maria del Fiore, designed by Arnolfo di Cambio (Colle di val d’Elsa, c. 1245 - Florence, 1310), had been completed, and the project had become irrimandable after the mighty thirteen-meter-high octagonal drum had also been raised above the tribune in 1413, which had made the construction of an eventual roof even more complex. For the design of the dome, the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore announced a competition in 1418: it was a challenging task, because it was necessary to design a structure that would be in harmony with the rest of the building, and above all it was necessary to think about how to get around the enormous practical and engineering obstacles that would inevitably arise. The competition, in which eighteen architects participated and submitted seventeen proposals (in addition to Brunelleschi’s, the Opera received designs by Manno di Benincasa, Giovanni dell’Abbaco, Andrea di Giovanni, Giovanni di Ambrogio, Matteo di Leonardo, Lorenzo Ghiberti, Piero d’Antonio, Piero di Santa Maria a Monte, Bruno di ser Lapo, Leonarduzzo di Piero, Forzore di Nicola di Luca Spinelli, Ventura di Tuccio and Matteo di Cristoforo, Bartolomeo di Jacopo and Simone d’Antonio da Siena, Michele di Nicola Dini, and Giuliano d’Arrigo), after various phases, consultations and new proposals were concluded in the spring of 1420: Filippo Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti (Pelago, 1378 - Florence, 1455), who eventually resolved to collaboratively design a model of the dome capable of surprising the Workers of Santa Maria del Fiore, were appointed Provveditori of the Dome on April 16, 1420, and they were joined by a third Provveditore, Battista di Franco, who would serve as the site’s foreman and was formally considered equal to his two colleagues. Ghiberti would oversee the work along with his colleague and old rival until 1425, the year from which the site was managed entirely by Brunelleschi.

The great architect had convinced the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore not so much because of particularly futuristic choices in terms of form or aesthetics, but mainly because of the practical solutions he had devised. For the dome there could only be one type of structure: an octagonal vault with sails, so much so that, if we define “dome” only as that structure consisting of infinite arches rotating around its own axis (and thus giving rise to a hemispherical dome), then Brunelleschi’s construction is not a dome, but is more properly, precisely, a vault. And given the size of the imposing vault, it would not have been possible to hold it up with timber reinforcements, the so-called ribs, because it was unthinkable to build a work of wood more than ninety meters high (the base of the dome is at a height of about 55 meters, plus 13 of the drum, and the height of the dome would have been 36.6 meters), and above all, although in 15th-century Florence one could still find carpenters capable of building gigantic reinforcements, the ribs would not have held the weight of the structure. Brunelleschi solved the problem by inventing a unique “self-supporting” dome. There were no alternative plans, however, and the decision was forced. The architect thus thought of using a double dome, inner and outer: in practice, the Dome of Santa Maria del Fiore is composed of two different domes, separated by a hollow space of about five feet and connected by twenty-four supports built over the segments of the inner dome.

|

| Brunelleschi’s Dome |

|

| Brunelleschi’s dome in the panorama of Florence |

|

| Probable portrait of Filippo Brunelleschi in the scene of Masaccio’s Saint Peter in the Chair (1423) in the Brancacci Chapel, Florence |

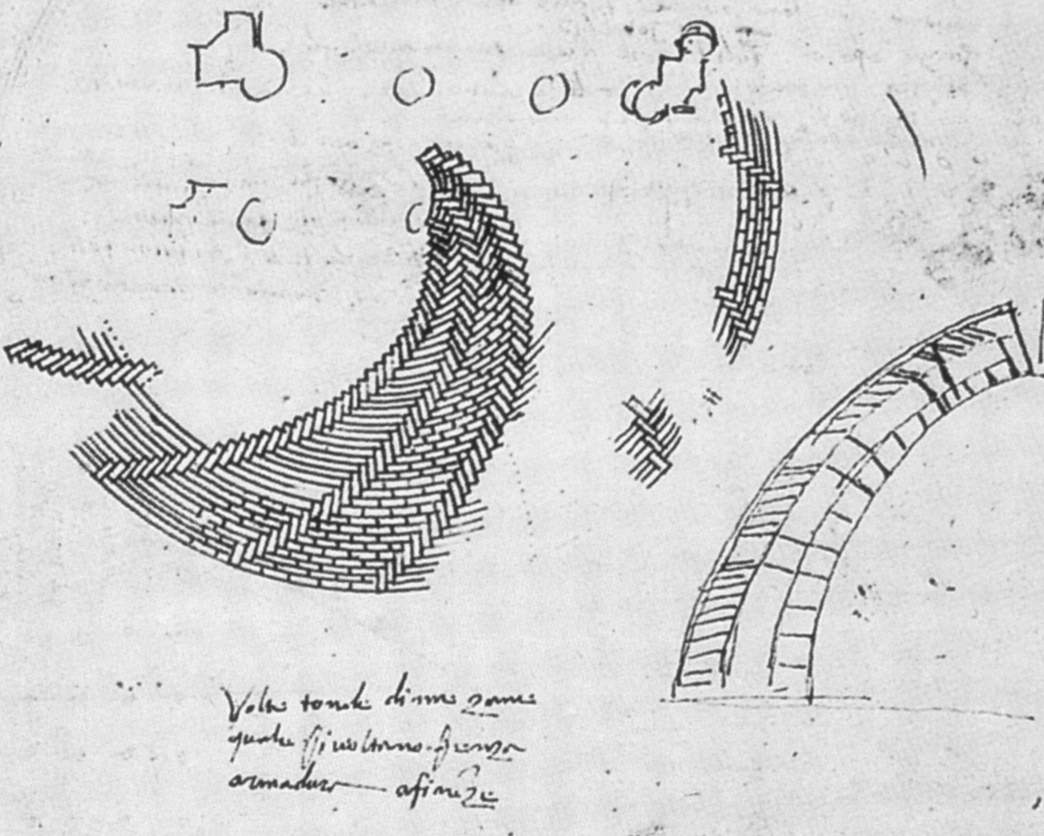

The solution envisioned by Brunelleschi solved several practical problems beyond that of the use of armor. With two domes, the architect had in fact succeeded in lightening the structure (a “full” dome would in fact have been much heavier), in giving the whole a greater static balance (to which the herringbone arrangement of the bricks with which the inner dome was made also contributed), and in better achieving certain practical and aesthetic ends: the outer dome, in fact, provided greater protection from moisture and the elements, and could take on the formal characteristics that the Opera di Santa Maria del Duomo expected (the outer dome, as Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, a biographer of Brunelleschi’s contemporary, wrote, was to make the structure come back “more magnificent and swelling”). Instead, the inner canopy supports the weight of the outer one.

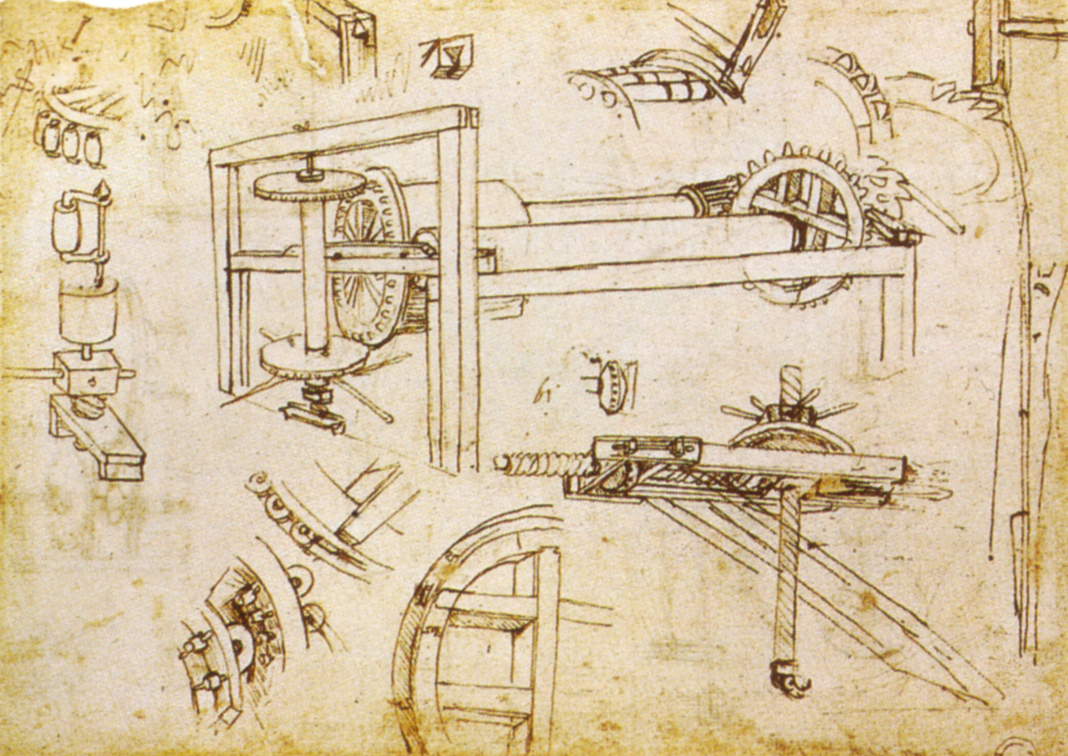

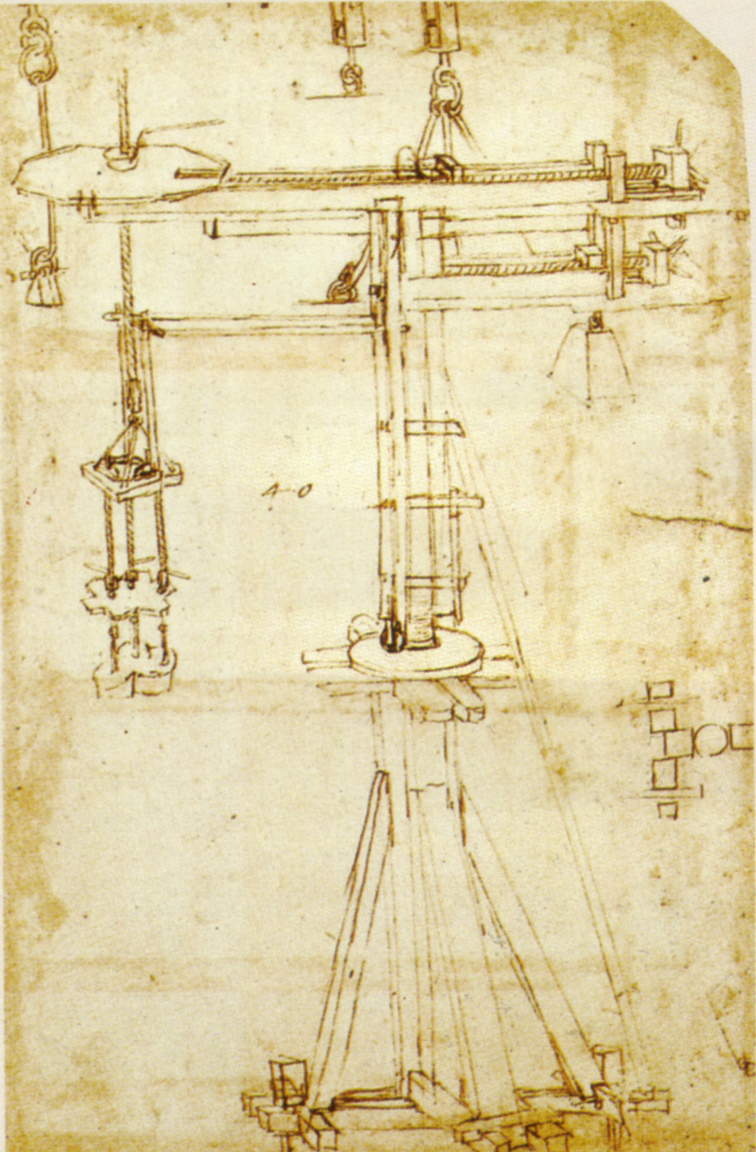

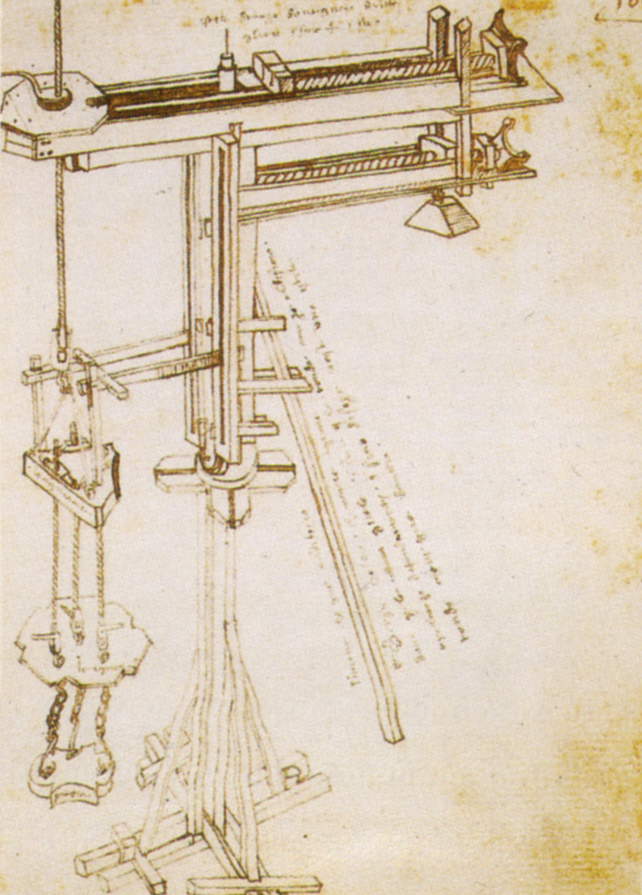

But Brunelleschi had also elucidated innovative solutions regarding the layout of the building site. In the pages of Giorgio Vasari ’s Lives dedicated to the great Florentine architect is a list of the practical arrangements with which Brunelleschi astonished the Dome Workers, for having “shown quellanimo che forse nessuno architetto antico o moderno nellopere loro aveva mostro.” the lighting of the staircases in the corridors between the two canopies so that “one could not strike in the dark,” the support points (or “appoggiatoi di ferri,” as Vasari calls them) to enable the workers to climb up and down the scaffolding better, and also the support points for the scaffolding reserved for those who in the future would have wished to decorate, with mosaics or with paintings, the interior of the dome. Then again, rainwater drains, holes and openings to keep the wind out of the building site, and to better protect the structure from earthquakes. Brunelleschi had then designed the machines necessary for the construction, so fascinating that even Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), who, as a 17-year-old, immediately wanted to study them as soon as he arrived in Florence (a passion that would not be limited to his youthful years: we find drawings of Brunelleschi’s machines in the Codex Atlanticus). They are machines so ingenious that they led many Renaissance architects to copy them in their drawings (unfortunately, there are no known drawings of the machines made by Brunelleschi’s hand). They include winches (some of them moved by pairs of horses that moved in circles), pulleys, spectacular revolving cranes hooked to scaffolding suspended in the void (and therefore could be used even at great heights).

Another important chapter was that of theorganization of work on the building site: indeed, Brunelleschi showed great management skills, and he omitted no detail in order to create a building site that would allow the dome to proceed expeditiously and the workers to operate in almost total safety. Bricklayers, blacksmiths and carpenters, woodworkers, lumber saws, chiselers, and coopers worked on the site: from the site’s annals we derive a total of 265 workers who in various capacities worked in the dome (they worked on six-month contracts, and usually between 60 and 70 workers were employed per semester), and we know for certain that there were only nine accidents, one of which was unfortunately fatal (it happened to a worker named Nencio di Chello, who in 1422 fell from a scaffold and died), while eight caused more or less minor injuries (only three did not return to work). An all in all low number, considering the fact that we are talking about a construction site in the early fifteenth century (and certainly at that time the culture of safety in the workplace was not the same as it is today), and extremely difficult and dangerous (so much so that the workers employed were almost all experienced workers: out of 265, as many as 259 were masters, 176 masters with qualifications, and only 6 were laborers or children). Not only that: no site workers were required to work at height (but those who did received higher pay). The primary cause of injury, however, was not workers’ falls from scaffolding or scaffolding, but were falls of construction material onto workers: the injured were still granted a paid convalescence period.

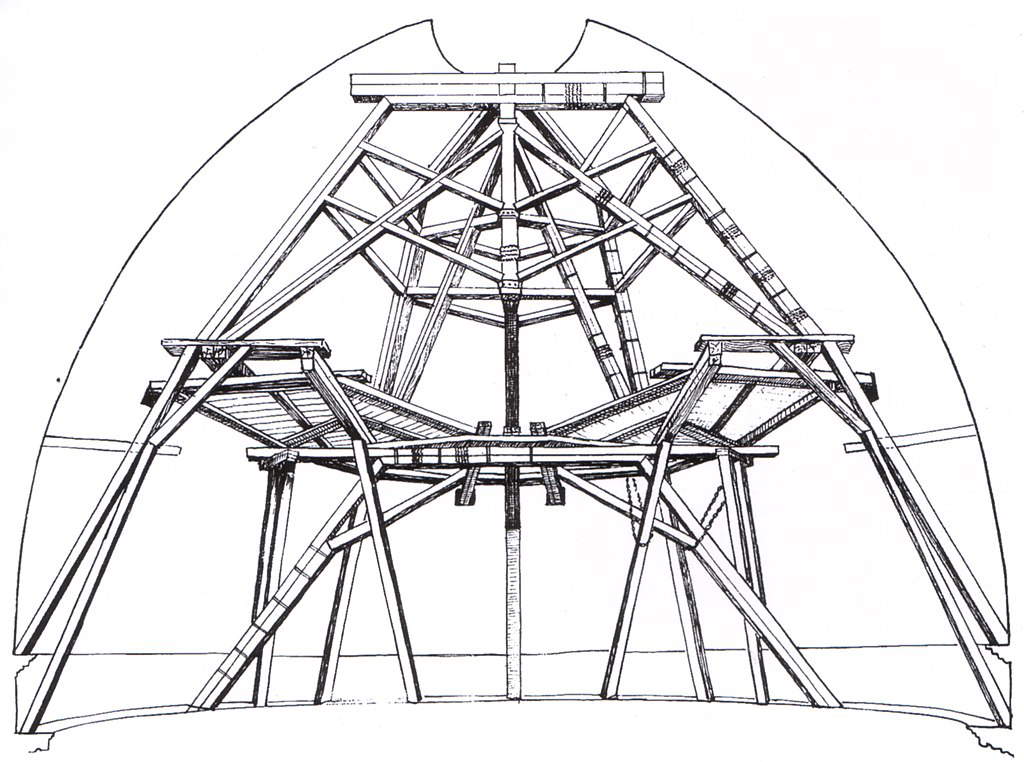

Brunelleschi had in fact taken care to ensure the best working conditions for the workers. For example, from documents we know of scaffolding with walls to prevent workers from having an open view of the void below them, scaffolding was equipped with parapets to prevent falls, and even Brunelleschi went so far as to give instructions on the quantities of wine to be given to workers (it should be noted, in fact, that the quality of water in fifteenth-century cities is not the same as it is today, and that wine was considered a much healthier drink: nevertheless, to protect the workers, Brunelleschi arranged for the wine to be watered down, and he also stipulated summary dismissal for workers who were found drunk). Then there is a famous anecdote reported by Vasari, according to which, when the construction site reached high altitudes, there was the problem of the loss of time to go out to eat: so the historian from Arezzo relates that Brunelleschi ordered “that taverns be opened in the dome with kitchens, and wine be sold there,” so that no one left their place of work except in the evening to go home, with the result that, Vasari again writes, “it was to their comfort, et all’opera utilità grandissima.” In fact, it must be said that Vasari’s is nothing more than a legendary episode: much more likely that the workers brought their own lunch from home, or even that Brunelleschi had arranged for food to be brought to the workers at altitude, through his machines. What is certain is that the great Florentine architect had a concern for the safety conditions and well-being of workers that are surprising in their relevance today. And again, Brunelleschi had also thought about how to make the scaffolding proceed as the elevation rose: if in the early stages of construction, when the sails were almost vertical, it was possible to install internal scaffolding, the curving of the sails upward made the use of external scaffolding a must, and eventually, when the inclination was too great, Brunelleschi imagined a scaffold suspended in the void in the center of the dome, resting on beams fixed at lower elevations. And at each stage of construction he had to see to it that all the sails proceeded harmoniously by converging toward the center: a task he succeeded in to perfection.

|

| Filippo Brunelleschi (attributed), Wooden Model of the D ome (c. 1420-1440; wood; Florence, Museo del Duomo). Ph. Credit Antonio Quattrone |

|

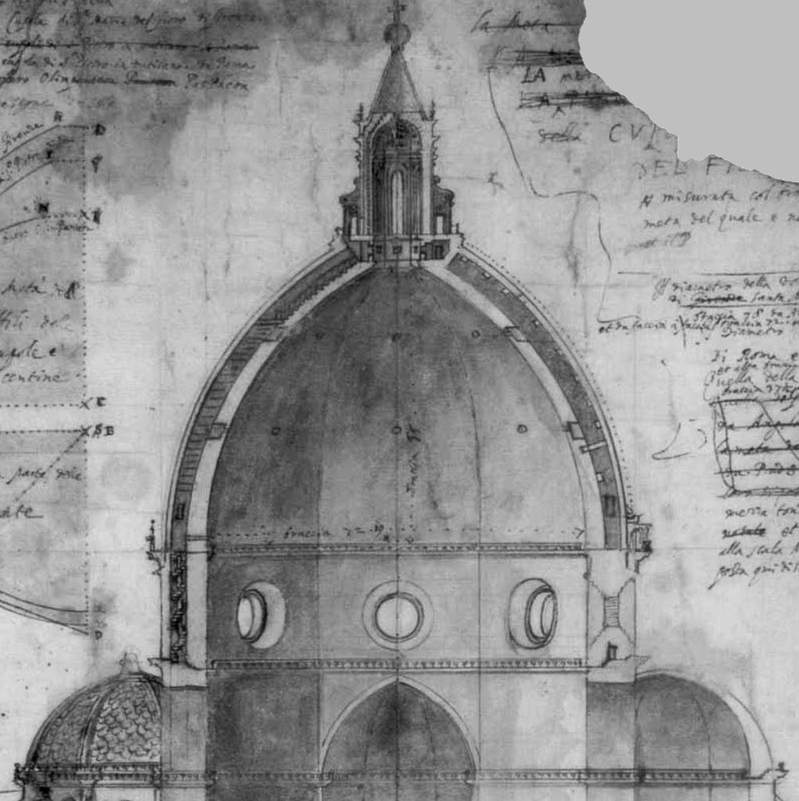

| Section of the dome designed by Ludovico Cardi, known as Cigoli, in 1613 |

|

| Antonio da Sangallo, Bricks arranged in a herringbone pattern (early 15th century; Florence, Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Giambattista Nelli, Reconstruction of the interior scaffolding of Brunelleschi’s dome (second half of the 17th century; Florence, Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Brunelleschi’s three-speed winch (c. 1480; Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Codex Atlanticus, c. 1083, verso) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Brunelleschi’s Revolving Crane (c. 1480; Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Codex Atlanticus, c. 965, recto) |

|

| Bonaccorso Ghiberti, Brunelleschi’s Crane (after 1446; Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, B.R. 228, c. 106r) |

But what were Filippo Brunelleschi’s reference models? One example of a dome with sails was already present in Florence: it is the dome of the Baptistery, which, however, does not have the elevation of that of Santa Maria del Fiore, although built on an octagonal plan like that of Santa Maria del Fiore. Again, perhaps Brunelleschi may have heard of some precedents in thePersian East, as scholar Piero Sanpaolesi has speculated: in fact, in Soltaniyeh, in present-day Iran, there is the mausoleum of �?ljeitü, which has the oldest double-domed dome found on Iranian soil, dating from between 1302 and 1312. Of course, the Florentine architect did not travel to Persia in person, but since the building, between the 14th and 15th centuries, enjoyed a certain fame in Europe as well, and since trade links between East and West were frequent anyway, it might not seem illogical that Brunelleschi drew inspiration from the illustrious model. The Pantheon has also been discussed at length: it is suggested, according to a suggestion that in any case is accepted by all critics, that Brunelleschi had traveled to Rome to study the works of the ancient Romans, and consequently the Pantheon’s dome, with a diameter of more than 43 meters, and which is still the largest concrete dome in the world today, must not have escaped his notice. Brunelleschi was to get important insights from it, especially in terms of the building’s statics, construction methods, and organization of work. The architect, for example, had noticed that the outer steps of the Pantheon’s dome rested on a circular inner shape.

“What appears extraordinary about Brunelleschi,” architectural historian Roberto Masiero and engineer David Zannoner have written, “is how he ideally disassembles the Pantheon’s dome, as one would the components of a machine or the gears of a clock. He disassembles it not in order to reconstruct it as it was in Florence, but to intuit its logic, structural workings, strengths and weaknesses, and to deduce, at the end of a completely conceptual procedure, that something radically different should have been made in Florence.” Indeed, the similarities with the Pantheon dome are few, on a formal and structural level: the materials change (bricks in the Florence Cathedral, concrete at the Pantheon), the shapes (an octagonal vault instead of a hemispherical dome), the type of structure (a double dome instead of a single dome), the fact that the dome would soar over the city and be visible from afar, while instead the Pantheon dome, which is considerably lower, remains hidden among the buildings in Rome. “In other words,” Masiero and Zannoner conclude, “Brunelleschi did not enact a mimetic analogy, but a conceptualization of processes; he did not reproduce, but disassembled the object to produce something else.”

|

| The Pantheon Dome in Rome. Ph. Credit Anthony Majanlahti |

|

| The mausoleum of �?ljeitü in Soltaniyeh |

|

| Brunelleschi’s dome in the panorama of Florence |

As mentioned, it took sixteen years to complete the work: it was March 25, 1436, when Pope Eugene IV solemnly consecrated the dome. The workers, on the other hand, celebrated later, since some finishing touches were missing, but they, too, were able to toast on August 3: again with a breakfast of bread, melons, and wine (this time, however, straightforward, to celebrate the event: it was only allowed on holidays, or to celebrate a particularly important advance in the work on the site). Exactly the same as sixteen years earlier. On August 31, the blessing of the Bishop of Fiesole also arrived, and there was a feast in the piazza, with a lavish banquet for the workers, the fabricators of Santa Maria del Fiore, and members of the Florentine clergy. All that was missing was the six-meter-high Lantern, which closes the structure: it, too, was designed by Brunelleschi (the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore approved his design on December 31, 1436), but the architect did not have time to see it finished because he passed away in 1446, and the work would not be finished until after his death. The Lantern (which, moreover, performs an important static function, since it contributes to the overall balance of the structure) was finished on April 23, 1462, with the work being directed by Brunelleschi’s successor, the aforementioned Antonio Manetti (Florence, 1423 - 1497), who respected Brunelleschi’s design to the letter (as attested by the wooden model now preserved in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo). The work could be called finally completed in 1472, when the bronze ball designed by Verrocchio (Andrea di Michele di Francesco di Cione; Florence, 1435 - Venice, 1488) was hoisted on the Lantern.

Brunelleschi’s Dome is one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of art not only because of its intrinsic characteristics, but also because it acts as a watershed between two eras, as the great architectural historian Leonardo Benevolo has written. The dome, we read in his History of Renaissance Architecture, “stands between the past and the future,” and “concludes the traditional image of the city, and gives the measure of future possibilities. Even today, Brunelleschi’s dome appears as a unicum, suspended between two epochs; it is in essence a Gothic work, not because of the pointed arch but because of the organic links with Arnolfo’s building and the importance of the structural commitment; as in the great cathedrals of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it is intended to touch the limit of the possibilities inherent in a given construction system. At the same time it possesses a new formal intentionality (largely detached from the surrounding building and grounded in the exaltation of geometric tracing) and is the first major work where architecture is not merely the high-level consultant to a collective body of performers, but the sole person responsible for form, decoration, structure, and site organization; thus it marks the paessage to a new architectural experience, the methodological foundations of which Brunelleschi himself is elaborating.”

Already the Florentines of 1436 could observe an incredible structure, for those years but also for today: an enormous red vault, punctuated by the eight white ribs that mark the shapes of the sails, which immediately became a very recognizable element of the landscape, since the dome can be seen even from several kilometers away. A source of pride and pride for the people of Florence (Leon Battista Alberti wrote, in stinging words, that the dome is a “structure so great, erta sopra e’ cieli, ampla a choprire chon sua ombra tutti e’ popoli toscani”). The clearest sign of Filippo Brunelleschi’s determination, stubbornness, wit and exceptional talent. And a structure that appears to us today above all as an extraordinary and universal symbol of human ingenuity.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.