The Roman poet Claudius Rutilius Namazianus, active in the fifth century A.D., was among the first to record in literature the wonder everyone feels at the Apuan Alps and the white marble that stains these mountains on the border between Tuscany and Liguria. In De Reditu Suo (“Of His Return”), a work in which Namazianus speaks of the return journey to Rome made starting from Gaul, his homeland (the poet was from Toulouse), he writes about the stop in Luni: “Advehimur celeri candentia moenia lapsu: Nominis est auctor Sole corusca soror. / Indigenis superat ridentia lilia saxis, / Et levi radiat picta nitore silex. / Dives marmoribus tellus, quae luce coloris / Provocat intactas luxuriosa nives” (“We quickly arrived at those candid walls: their name is that of the sister who shines with sunlight. With indigenous stones she passes the smiling lilies, and the stone shines with a mild light. Land rich in marbles, which with its light of colors sumptuously defies the immaculate snow.”). For Rutilio Namaziano, in essence, what we know today as “Carrara marble” was able, with its light, to rival lilies and snow. In these famous verses we can appreciate a sentiment that can be found in the recent history of Apuan marble, that is, the last five hundred years, from the Renaissance onward, when the material extracted from the Carrara quarries became particularly beloved for its intrinsic characteristics, namely, its luster, its whiteness, its brilliance, which represented extremely relevant elements for modern monumentality, also because the aesthetic properties of marble could easily be associated with positive values (just think of white as a synonym for purity). Although it is improper to refer to a Latin poet to emphasize a concept that is affirmed in the modern age, it should nevertheless be remembered that these verses were much quoted, especially in the nineteenth century, to extol the qualities of Apuan marble, the excavation of which began after 155 B.C., the date of the final subjugation of the Apuan Ligurians to the Romans.

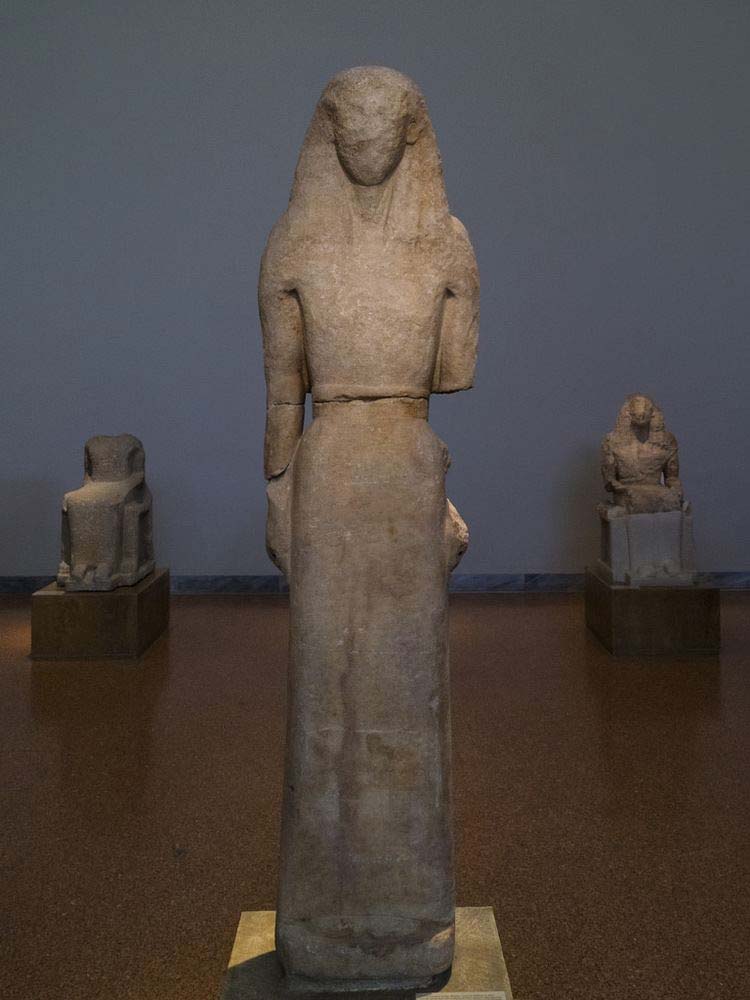

Of course, the Romans were not the first to carve in marble, since the earliest marble sculptures we know of come from ancient Greece: the Kore of Nikandre, a statue from the mid-7th century B.C., represents the earliest known example of marble sculpture depicting a life-size human being. Marble sculpture, however, is even older: for example, several small artifacts from the Cycladic civilization also made of marble have come down to us (these are small votive statuettes made of marble due to the fact that this material was found in great abundance in the Cyclades). The term “marble” itself is of Greek origin: it derives from mármaros, meaning “shining stone,” although its luster, in ancient times, was not the characteristic that made the Greeks first and the Romans later fall in love with marble. The abundance of the use of marble in ancient statuary is due to much more prosaic factors: marble was found in abundance in Greece and its islands, and consequently it was an easy material to transport and work with, so much so that Greek sculptors would specialize in it.

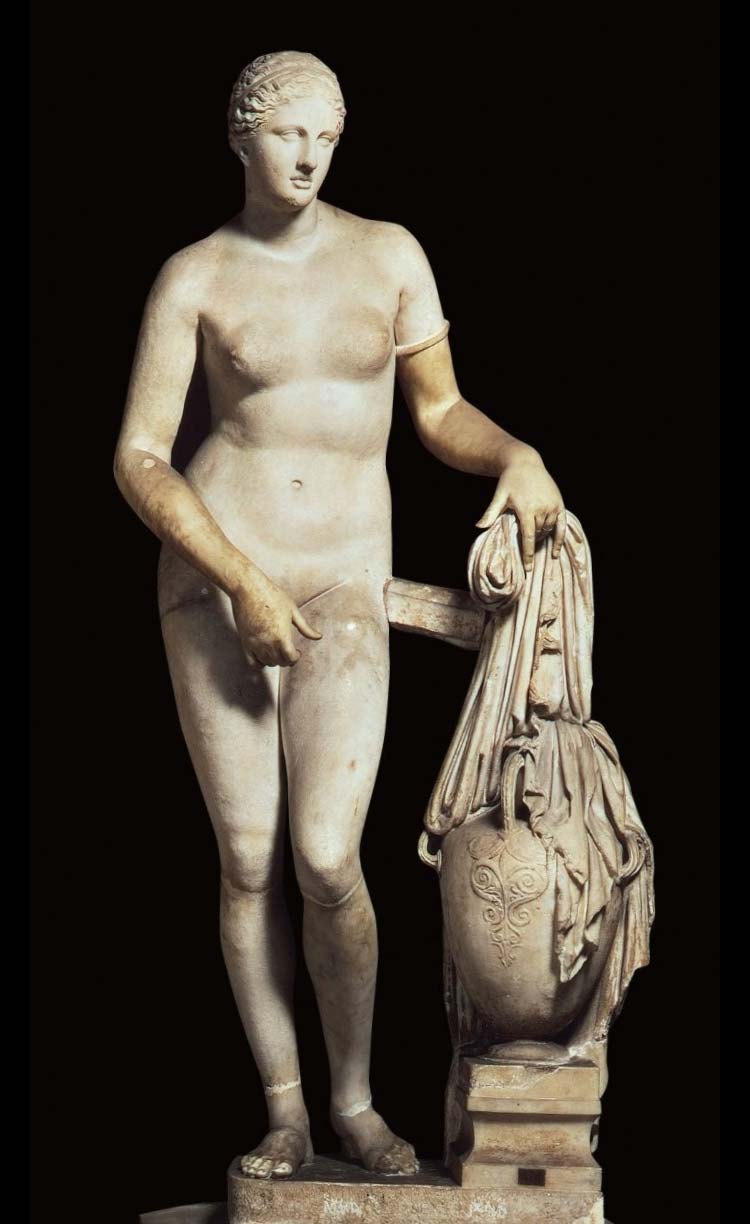

In fact, it should be kept in mind that the Greeks and Romans colored their statues: the idea of Greek and Roman sculptures with marble left in its natural coloring is actually the result of a historical misunderstanding that, since the Renaissance, has endured very hard until the present day, because it is difficult to eradicate from our imagination the idea that ancient statues were white: actually, one might say trivializing a little, because Greeks and Romans aspired to the natural, and because the natural is colored, Greeks and Romans could not let their statues remain white. As the centuries passed, ancient statues, buried in the earth or exposed to the elements, lost their color, and as a result, found centuries later, in less than optimal conditions, they appeared in the natural color of marble, and therefore white. Recently, many ancient art experts have been doing their best to convey to us the correct image of ancient statues: such is the case with German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann, who imagined a series of painted reproductions of celebrated statues of antiquity (such as theCnidian Aphrodite or theAugustus of Prima Porta now in the Vatican Museums) for an exhibition that began in 2003 at the Gliptothek in Munich and has since toured the world: Entitled Gods in Color, it has been held at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Liebieghaus in Frankfurt, the University of Heidelberg, the Archaeological Museum in Madrid, the Medieval Museum in Stockholm, the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, the Getty in Los Angeles, and several other institutions, among others.

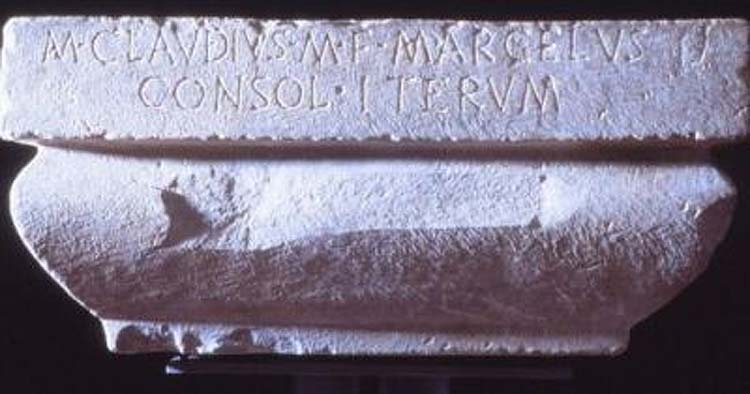

One of the oldest Roman works in marble can be found at the National Archaeological Museum in Luni and is the base of the statue dedicated to Marcus Claudius Marcellus, the general who in 155 B.C. succeeded in definitively defeating the Apuan Ligurians.It was from this date that the Romans began to intensively exploit the marble from the quarries of Carrara, which was initially used mainly as a building material (visiting Luni one will easily notice how several elements, such as columns and bases, are made of marble). It will therefore take some time, that is, until the middle of the first century B.C., for Luni marble to become a widespread material in Rome as well, and always with use in architecture, replacing traditional materials such as wood and terracotta.

When we talk about "Roman art," we need to remember that we are talking about an art that knows different developments: initially, as can be seen by looking at the Frieze of the Basilica Aemilia, it is an art that basically imitates Greek art. Greece is occupied by the Romans in 146 B.C.: a historical fact of considerable cultural value since the Romans begin to develop a real passion for Greek art and become proud and assiduous importers of Greek statues, also because at least until the late Republican age Rome will not have a defined artistic identity nor will it develop a coherent and spontaneous artistic sensibility, much less will there be programs for the development of an artistic civilization proper: for this reason, until shortly before the birth of the empire, it is essentially an art of imitation. However, the role of marble is already clear and defined: already in the age of Caesar having marble statues, or the house decorated with marble elements, is considered a sign of prestige.

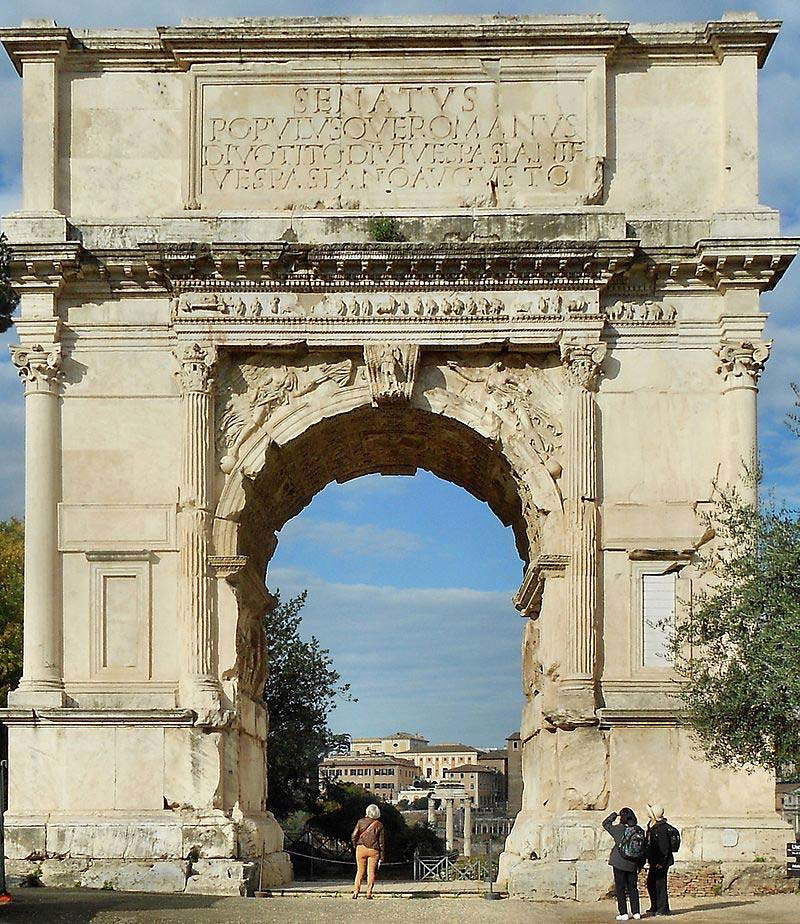

The situation changes considerably in the imperial age: with the new ordering of the state, Rome’s cultural policy also undergoes a transformation from the time of Augustus. Before the empire, art went on basically on its own, there was no coherent cultural project, and as anticipated it was mostly imitation sculpture. With the empire the situation changes, since one of Augustus’ first requirements is to endow the empire with a precise cultural identity, with the aim of consolidating the empire’s authority and prestige. Augustus’s project also passes through letters (think for example of theAeneid), and it is precisely under Augustus that a celebratory style of art begins, with marble as one of its favored materials. Marble thus begins to be in high demand not only for public but also for private construction, and of course this demand is at the root of Luni’s fortunes. And it is precisely in this epoch that a strong monumentality in marble is clearly developed, moreover original, because thetriumphal arch is a Roman invention, born in the Augustan period, which had no practical function, but only celebratory, and was therefore the maximum expression of the typically Roman idea of "monument," that is, a public art to remember and celebrate an event in which the community recognized itself. A function moreover enhanced by the fact that triumphal arches were isolated from other architecture, to make their symbolic value even clearer. For example, in the case of the Arch of Titus, the oldest surviving triumphal arch in Rome (although older ones exist in Italy), the intent was to celebrate the triumph of Emperor Titus against the Jews in 70 CE, and as has often been the case throughout Roman history it was not erected by the person directly concerned, that is, by Titus, but by his successor, Domitian, the last emperor of the Flavian dynasty, who intended with this work to celebrate his brother Titus, who by the time this monument was built (starting in AD 81) had already been deified. Triumphal arches can be considered works somewhere between architecture and sculpture, because they were not only imposing and easily recognizable structures in the urban context, but were also finely decorated by the best artists, with panels illustrating exploits of the personage to whom the arch was dedicated: in this case, the triumph of Titus, who is crowned by the personification of Victory, and the procession of the soldiers of his legions bringing to Rome the spoils of the Jewish war (thus, one sees the works that the Romans took away from the temple in Jerusalem, beginning with the seven-armed candelabra).

The fall of the Roman empire also coincides with a rather unfortunate period for marble quarries, since for centuries quarrying was practically zeroed out, and in the few cases where building was done with marble it was done through the reuse of previously used material, through the spoliation of ancient buildings. It was very common, for example, to reuse columns for the construction of churches, or even to use sarcophagi as altars. To witness a new flourishing of marble, it would be necessary to wait until the year 1000, when quarrying would resume at a sustained pace.Interestingly, the Carrara Cathedral is the oldest building made entirely of Apuan marble after antiquity, although it is not the oldest in the broadest sense to make use of Apuan marble, since, before the Carrara Cathedral, marble from the Lunigiana quarries was widely used in San Miniato al Monte in Florence or the Pisa Cathedral: the Pisan cathedral, in particular, is the first building after antiquity in which marble was used, giving a new start to quarrying.

The Middle Ages also saw the beginning of the myth (or at least such is the case for the people of Carrara) of great artists personally traveling to the city to select the marble from which their masterpieces would be born. The first of whom we hear of is Nicola Pisano, who moved to Carrara for some time in 1265 to contract for the supply of the marbles that would be used for the pulpit of Siena Cathedral and to arrange the transportation (the blocks would thus be extracted in Carrara and sent to Pisa, the city where they would be worked since Nicola Pisano resided there), and finally the shipment to Siena. The myth of the artist arriving in Carrara and choosing the blocks would later involve many other figures, above all that of Michelangelo Buonarroti, who stayed in Carrara several times to choose the marbles that would give life to his masterpieces: the first time when he was just over 20 years old, in 1497, when he was commissioned to sculpt the Vatican Pietà for French cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas. Initially intended for the chapel of Santa Petronilla, which was located near St. Peter’s Basilica, it was later moved inside the basilica in 1517, and that is still where we admire it today. Curiously enough, Michelangelo first went to Carrara at a time of the year not particularly suitable for ascending the quarries, that is, in the month of November: it is therefore possible to imagine the effort that was made at the time to ascend the quarries, made even more epic by the fact that the means of the time were certainly not modern ones. All aspects that helped fuel the myth of Michelangelo defying the elements, defying the forces of nature, defying matter, and succeeding in quarrying his immortal works from marble.

Instead, to arrive at the rebirth of the monument as the ancients understood it, that is, as a structure or as a celebratory work freed from an architectural context, we will have to wait for Donatello, the first modern artist to create a monument in this sense. This is the monument to Gattamelata, the condottiero Erasmo da Narni, made between the 1540s and 1550s, and can still be seen today in Padua in front of the basilica of St. Anthony: it is the first equestrian monument erected since antiquity, and it celebrates a condottiere who had fought for the Republic of Venice (the state in which Padua was located at the time), and to erect it would have required a special authorization from the Senate of the Republic, due to the fact that the celebration in the public square of a modern personage, moreover recently deceased, was a totally new fact for the time, and consequently it would have been essential to make sure that the decision to erect the monument resulted from a participatory process. Indeed, the work had been commissioned not by the Republic, but by Erasmo da Narni’s son, but since the monument would be placed on a public square, the creation of this sculpture would become a matter of public debate. The monument to Gattamelata is not, however, the first equestrian statue in the broad sense, since some works such as the equestrian statues of the lords of Verona are much earlier, but they were designed to decorate the top of arches (their monumental burials), and were thus funerary monumentality.

The first important case of marble monumentality in a public square is Michelangelo’s David, carved from a single block of marble previously hewn (first by Agostino di Duccio and then by Antonio Rossellino), although it is interesting to note that the David was not initially born as a monument, because it was to decorate one of the buttresses of Florence Cathedral. It is therefore a very interesting case of a work that completely changes in significance shortly after its completion: we are in 1504, Michelangelo has almost finished sculpting the work, and the problem of where to place it ar ises in Florence since several problems had arisen in relation to its intended location (in fact, the initial plan called for ten other works of the same proportions, and it had become unthinkable for reasons of timing and cost). In addition, it was still a five-meter-high statue, so there was the problem of raising it to the originally established height, and a question of an artistic nature arose, moreover: the David was a work so out of the ordinary that it was considered “wasted,” so to speak, for a location eighty meters high. The Republic of Florence therefore assembled a commission, consisting of the greatest artists of the time (among others: Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, Filippino Lippi, Piero di Cosimo, il Perugino, Lorenzo di Credi), and decided on Filippino Lippi’s idea, namely to locate the work near the entrance to Palazzo Vecchio (where the nineteenth-century copy stands today), in place of Donatello’s Judith which, another interesting case, was originally conceived as a decoration for a fountain (or at least this is the most credited hypothesis) and then, after the expulsion, of the Medici, commissioners of the work, in 1494 placed in Piazza della Signoria to signify victory over tyranny. Michelangelo’s David also underwent a change of meaning in these terms, since, placed on the public square, it no longer represented a work of a religious character, but became a “secular” monument, a symbol of the civic virtues of the Florentine Republic: the strength and intelligence of the city, the Republic’s victory over tyranny, and courage in confronting enemies.

The history of public monumentality, moreover, always continues in Florence, where, a few decades later, having achieved a certain political stability, Cosimo I becomes the first modern ruler to initiate an intense program of public celebration of the state, with monuments erected by him and his successors not only in Florence but in all the cities of the grand duchy to exalt Medici power. The first of these monuments was erected even before Cosimo became grand duke: the year 1562 runs and the work is the Column of Justice in Piazza Santa Trinita, which uses a reused column (it came from the Baths of Caracalla and was donated to the then duke of Tuscany by Pope Pius IV). Then, in 1581, a red porphyry statue by Francesco del Tadda depicting Justice (hence the name) was added to it, with clearly celebratory intent. Naturally, in this celebratory program of the Medici, marble takes on an important role: one of the best-known examples is the Monument of the Four Moors in Livorno, celebrating the victory of the Knights of St. Stephen over the Barbary corsairs (the Moors therefore are not slaves as one might believe, but pirates captured during a war, and it will be worth noting that the Barbary corsairs reserved the same treatment for their enemies, white men). The monument is surmounted by a statue of Ferdinand I de’ Medici, made starting in 1595 by Giovanni Bandini, who sculpted it directly in Carrara, and then erected in 1617 by his successor Cosimo II. The Moors, on the other hand, are in bronze and are the work of Pietro Tacca, a sculptor from Carrara who, moreover, very curiously would have specialized in bronze, rather than marble, the local material.

With a leap of a hundred and fifty years we come to Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who in a well-known passage in his 1764 History of Art in Antiquity wrote: “The essence of beauty is not color but is form. Since white is the color that repels most light rays, and consequently the one most easily perceived, a beautiful body will be all the more beautiful the more white it will be.” We can perhaps identify Winckelmann as the main person responsible for our perception of ancient monuments, since it is his conception of an ideal of purity destined, on the one hand, to become foundational forneoclassical aesthetics, and on the other to condition the modern idea of monument itself. As mentioned above, the pigments that the ancients used to color marble statues were easily perishable, and consequently at the time of their discovery it was common to think of statues in antiquity as white. Moreover, Winckelmann accorded a special predilection to white, and as a result one can easily understand why, when one thinks of ancient statues, it is almost spontaneous to immediately think of pure, ethereal, beautiful statues in white marble: an image that conditioned the entire neoclassical aesthetic and that consequently resulted in the most beautiful monuments of the time being made of white marble. A conditioning that, moreover, continues to this day, since even we contemporaries consider it much more in keeping with our sensibilities to leave a marble statue white, thus avoiding coloring it.

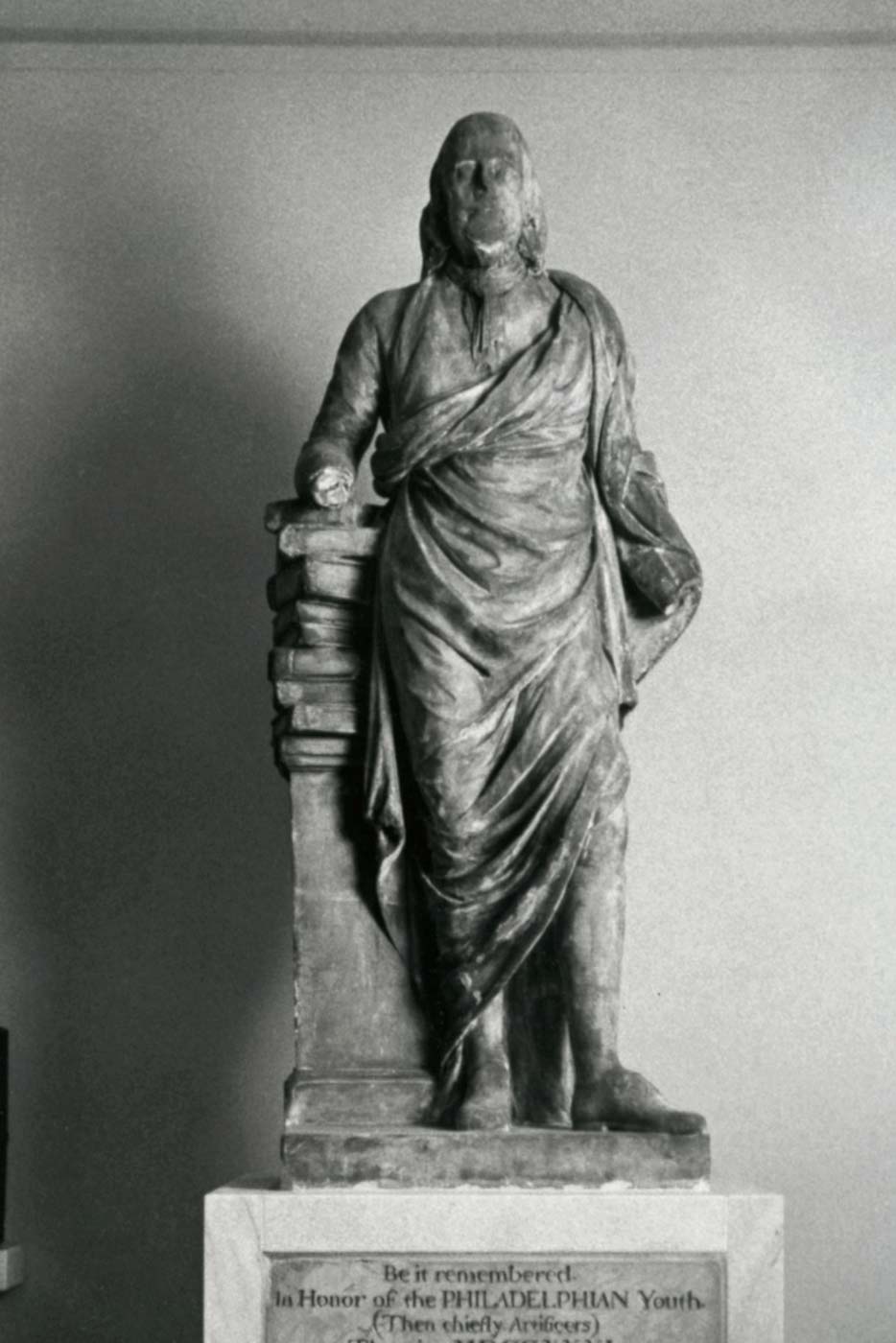

Thus, in the eighteenth century, the city of Carrara becomes an important center because marble monumentality knows an exceptional spread throughout the world. Quarries were active as never before, and artists took to them with a certain intensity (think, for example, of Antonio Canova, author of many of the most important commemorative monuments of the period at the turn of the nineteenth century). The neoclassical period also saw the flowering of that local school, which Carrara, in the course of its history, had never had until then (one of the most interesting products of that school is the monument to Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, created by a sculptor from Carrara, Francesco Lazzerini), since the first important sculptors from Carrara, active in the seventeenth century (Pietro Tacca, Giuliano Finelli, Andrea Bolgi, Domenico Guidi, and many others) would all work far from Carrara. The first artist to open a workshop of some importance in the city would be Giovanni Baratta, in 1725: this was an important event, because Baratta succeeded in starting a tradition of artistic marble working in the same place where marble was quarried and hewed. Later, the establishment of theAcademy of Fine Arts in 1769 and the continued demand for marble that began in the second half of the century would contribute to the flourishing of a busy local school, especially in the 19th century, with sculptures coming out of the workshops of Carrara sculptors and leaving for all over the world.

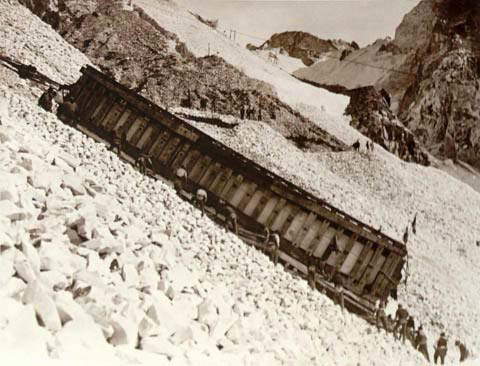

Another period of intense use of Carrara marble in public monuments is the Ventennio Fascista: the most famous marble monument is probably the obelisk of the Foro Italico, the sports complex entirely designed by the Carrara architect Enrico Del Debbio, who would keep it occupied from 1927 to 1932. The Foro Italico was created in connection with the typically fascist cult for physical vigor and performance, as a result of which sports were considered a very important part of the fascist’s life. The Foro Italico was to be inspired by the architecture of imperial Rome: hence the choice of the obelisk, which, though a celebratory form originating in Egypt, would have been widely used in Rome. The block from which the obelisk in the Foro Italico is carved would go down in history as the "Monolith,“ the largest block that has ever been quarried in Carrara in all its centuries of history (it was a 300-ton block), and it is interesting to note, moreover, that all the operations necessary for its extraction and transport would become functional for the propaganda of the regime, so much so that there were even those in the city who would comment on the event with certain irony: legend has it that a certain Gregorio Vanelli, a Carrara personality of the time, would have called the operation ”the biggest sawing of the century,“ with a double meaning well understood by the locals (”segata“ understood as the act of sawing marble, but in the Carrara dialect it is the equivalent of the Italian ”cazzata").

Today, the formula of the celebratory monument such as those seen so far is no longer in use, as today’s society has found other ways to eternalize and celebrate the memory of notable and powerful people, and one such way is the construction of important buildings, as preferences today have shifted from sculpture to architecture. In essence, while it used to be sculpture that embodied all the desires for continuity and ambitions for eternity cultivated by human beings, in the contemporary world it is architecture, on the other hand, that takes on these aspirations, and it is the grand buildings and large architectural complexes that have become probably the most obvious symbols of contemporaneity. Then there are other forms of monumentality: for example, certain films that actually celebrate certain characters, rather than critically reconstructing their events, have become a form of contemporary monument that reaches the public in perhaps even a simpler and more direct way than a statue erected on a square would.

The use of marble, however, continues to this day, since it has become one of the materials used in the decoration of the environments of contemporary buildings, and it is still much sought after even for the most important buildings, made by the great architects who very often employ marble for the decorative apparatus of their buildings. For example, the lobby of the twin towers in New York was made of Carrara marble. One of the fragments of that lobby, moreover, became a work of art by a contemporary French artist, Cyprien Gaillard, who claims to have received it as a gift from the engineer who led the debris disposal of the twin towers. During the recent debate around monuments, there has long been discussion of how monuments change meaning over centuries if not years, and this fragment, preserved in Carrara’s municipal collections, is a clear example of how a monument, part of which is built of Carrara marble, has changed its meaning from being a material that celebrates the economic power of the world’s leading financial center, the same material has become a symbol of memory that lasts forever, a symbol of art that survives barbarism, and a symbol of return as well, since the marble has returned to Carrara and today can be admired at the Museum of the Arts in the City of Marbles.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.