Houses in the foreground with trees and vegetation in the background and all around, boundless hills with lighthouses, gas stations and deserted roads, railroads with sunsets on the horizon: the landscapes of Edward Hopper (Nyack, 1882 - Manhattan, 1967) seem enclosed in a muffled bubble where silence reigns. Often depicted without any human presence, even when a female or male figure appears inside or just outside the doorway of a dwelling there is a sense of the total absence of sound or speech. There is no dialogue, no sharing. What Hopper represents is a mute and melancholy landscape. And the impression is often that of being in front of infinite landscapes, of which, however, only a part is visible to the observer, a small portion of an immense whole.

Hopper is the painter who, more than any other, has been able to recount in depth the pure Americanness of the boundless landscapes, where everything seems infinite, where distances stretch disproportionately, where between one town and another run miles and miles to be traveled on endless roads interrupted only by gas stations. The true American soul is reflected in the vast immensity of spaces that seem to have no boundaries; it is not the one made of sequins and glitter, stars and Hollywood, but rather the one where progress, the transformation of the landscape by man has caused loneliness. Hopper has well portrayed the concept of a melancholy America, emphasizing the dark side of progress that, contrary to what one would think, has led to greater estrangement between individuals. Hopper’s American landscapes are clear, linear compositions: houses are frequent, symbolizing human settlement; images of railroad roads running horizontally stand for man’s desire to conquer large and extensive spaces; an immense sky with particular luministic details, such as the full midday sun or the twilight glimmer, hints at the infinity and constant transformation of nature; a lighthouse can become a landmark in the vastness of the sea and coastline. This sad and lonely face of America has also been depicted in several successful films: examples include Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, Kevin Costner ’s Dances with Wolves , and Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas . The latter has even created, on the occasion of the currentexhibition running until September 20, 2020 at the Fondation Beyeler dedicated to Edward Hopper, which features an exhibition of sixty-five of his works between 1909 and 1965, a 3D short film entitled Two or Three Things I know about Edward Hopper: a personal tribute to the American artist through an on-the-road journey across the United States in search of Hopper’s "American spirit." The celebrated filmmaker traveled America to gather his impressions of the painter and bring to life a cinematic work in which the artist’s most famous works, such as Morning Sun or Gas, are seen materialized in evocative moments on film, allowing the viewer to literally step into the American landscape and melancholy scenery depicted in Hopper’s paintings. Known throughout the world primarily for his scenes of urban life in domestic interiors, or at any rate on the doorstep, and in public gathering places where nevertheless silence and monotony are always perceived, the landscape aspect of his art is still little addressed in exhibitions: the extensive review that the Fondation Beyeler has devoted to this theme is therefore almost unique. In parallel then, the famous Swiss museum venue has chosen to offer its visitors an additional exhibition that has to do with silence: Silent Vision. Images of calm and quiet at the Fondation Beyeler in fact intends to traverse its collection, fromImpressionism to the contemporary, following the theme of calm and quiet. Modernity, as an age of progress characterized by movement and speed, has seen the emergence of an opposite desire for deceleration that has been artistically expressed with new images of stillness and silence.

|

| Edward Hopper, Gas (1940; oil on canvas, 66.7 x 102.2 cm; New York, The Museum of Modern Art) |

|

| Win Wenders, Two or three things I know about Edward Hopper (2020; fotogramma da film) |

|

| Win Wenders, Two or three things I know about Edward Hopper (2020; frame from film) |

Born in 1882 in Nyack, a small town not far from New York City, Edward Hopper briefly attended illustrators’ school before studying painting at the New York School of Art. There he was mainly influenced by Robert Henri, particularly on the notion that everyday American life could hold new themes for him to address in art, but it also taught him to appreciate great masters such as Diego Velázquez, Jan Vermeer, Francisco Goya, and Édouard Manet, artists who had begun to provide a glimpse of reality. He later stayed in Paris, conducting his studies in museums and on the streets, and at first assimilated the principles ofImpressionism:he was influenced by it in terms of careful observation and the use of color and light. The painter made mainly oil paintings, but he also devoted himself to etching. His first painting to be purchased to become part of the collections of the newly founded Museum of Modern Art in 1930 wasHouse by the railroad, in which the characteristics of his style could already be seen: well-delineated forms in bright landscapes, a composition built from an almost cinematic point of view, and a sense of eerie tranquility. Beginning with an exhibition held at MoMA itself a few years later, Hopper was celebrated for his highly recognizable style, where cities, landscapes and domestic interiors were pervaded by silence and a sense of estrangement. Often without any human figures, his scenes with deserted cities, empty gas stations and equally empty railroads are symbolic of silence and loneliness; if present at all, people rarely appear in their own homes, but in hotel rooms, bars or restaurants always shrouded in that alienating aura of tranquility.

The artist and his wife, Josephine Verstille Nivison, also an artist, spent every summer from the 1930s to about the 1950s in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where they owned their home: there are many paintings set on Cape Cod. Although in an era of prosperity and prevailing optimism, his art continued to show the strong sense of loneliness in postwar America. However, until his death in 1967, Hopper enjoyed the acclaim of the public, which elected him as a major exponent of the new generation of artists of American realism, defined as depicting the everyday lives of ordinary people in a contemporary society.

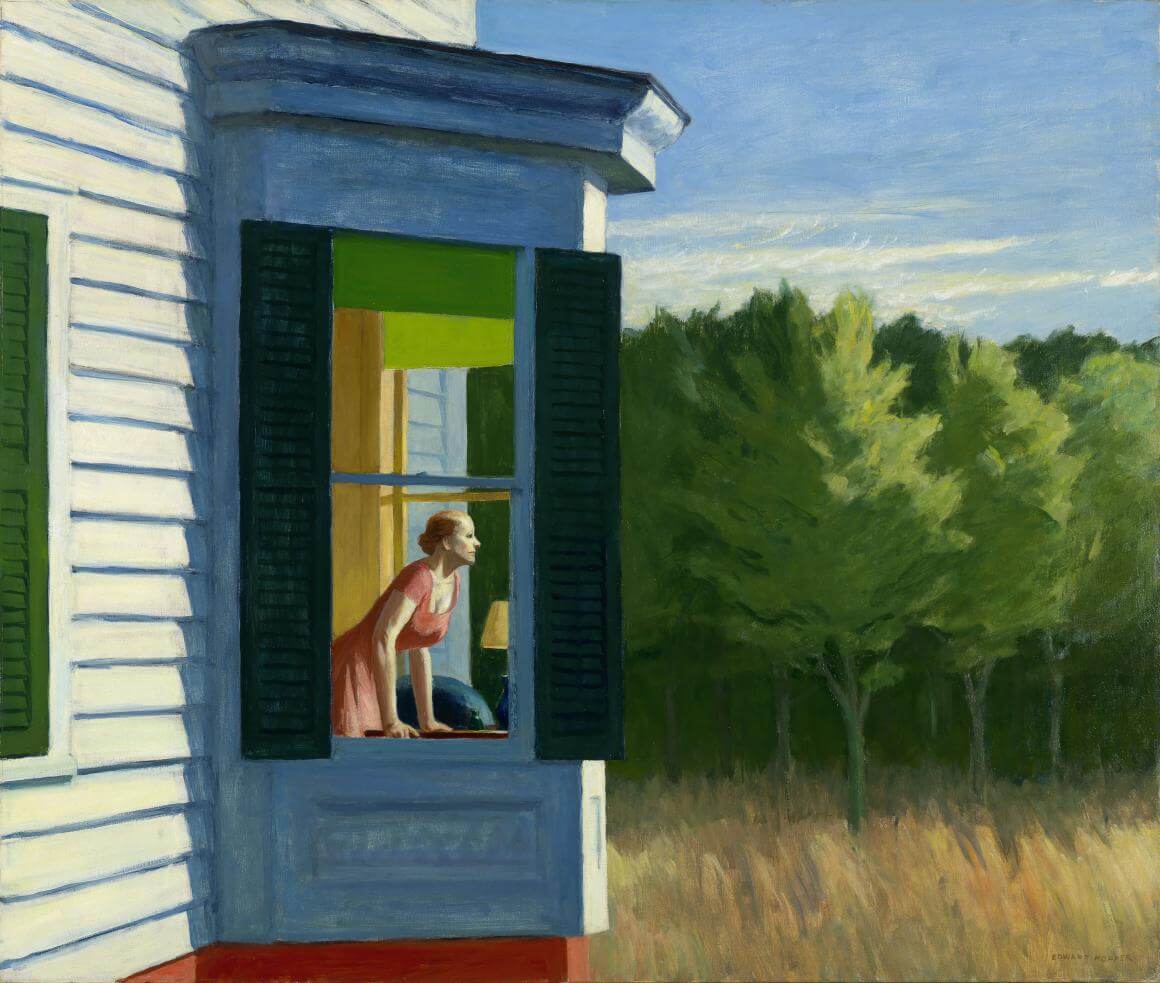

Set on Cape Cod is one of the artist’s most famous paintings, Cape Cod Morning. The work, created in 1950 and now housed in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, appears to the eye to be divided into two parts: on the right are trees forming a dense forest in the background; on the left is a white house with green shutters, at whose bay window faces a woman in profile with her body leaning forward; both the body and the gaze of the female figure are turned outward, toward something the viewer cannot see. It is possible to catch a glimpse of the table on which she rests both hands, in a tense position, a lamp and the back of an armchair, but the painter, as he is wont to do, does not reveal to the viewer the subject that causes so much attention from the woman. The female figures in Hopper’s paintings are modeled on his Jo, his wife Josephine Nivison. This work, like many of the artist’s others, documents a moment of everyday life, which, however, the audience is not allowed to fully see, leading one to imagine what lies beyond the depicted scene. As poet and essayist Mark Strand points out in his Edward Hopper. A Poet Reads a Painter, “Hopper’s paintings are short, isolated moments of description that suggest the tone of what will follow them just as they bring to the foreground the tone of what preceded them [...] The more theatrical, mise-en-scène-like they are, the more they prompt us to imagine what will happen next; the more true to life they are, the more they prompt us to construct the narrative of what has gone before.” He adds in a statement that fits right on the woman at the window, “Hopper’s people seem to have no occupations whatsoever. They are like characters abandoned by their scripts who now, trapped in the space of their own waiting, must keep themselves company, with no clear destination, no future.”

|

| Edward Hopper, Cape Cod Morning (1950; oil on canvas, 86.7 x 102.3 cm; Washington, Smithsonian American Art Museum) |

|

| Edward Hopper, Second story sunlight (1960; oil on canvas, 102.1 x 127.3 cm; New York, Whitney Museum of American Art) |

|

| Edward Hopper, Lighthouse Hill (1927; oil on canvas, 73.8 x 102.2 cm; Dallas, Dallas Museum of Art) |

The same is true of the protagonist couple in Second Story Sunlight, which Hopper painted in the last period of his life, seven years before his death, and which is now housed at the Whitney Museum of American Art. On the balcony of a house, a woman is sitting sunbathing in a bikini on the railing, while another woman is reading the newspaper, enjoying the sun’s rays warming her face. Central here becomes the use of light: the facades of the buildings are fully illuminated by direct sunlight and the human figures depicted enjoy the benefit. Under the intense sunlight, the colors are much brighter than in the shaded areas, particularly the forest around, thus creating a play of light and shadow.

A male figure stands out (and almost blends in) in the famous 1940 painting Gas, housed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Here, too, there is a juxtaposition of light and shadow: on the one hand the impenetrability of the forest that frames the scene, on the other the artificial light coming from the gas station windows. The three gas pumps stand in the middle, and the presence of the man adds nothing to the scene; his presence or absence is irrelevant to the entire composition. In Portrait of Orleans, a 1950 painting preserved at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the sign of a gas station is noted in the foreground on a curve in the deserted streets of Orleans. A series of buildings is depicted in front of trees, and only one car drives down the street in the distance. A sense of loneliness and absence also pervades the built-up area of the well-known American city.

|

| Edward Hopper, Portrait of Orleans (1950; oil on canvas, 66 x 101.6 cm; San Francisco, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco) |

|

| Edward Hopper, Road and houses, South Truro (1930-1933; oil on canvas, 68.4 x 109.7 cm; New York, Whitney Museum of American Art) |

|

| Edward Hopper, Cobb’s barns, South Truro (1930-1933; oil on canvas, 74 x 109.5 cm; New York, Whitney Museum of American Art) |

|

| Edward Hopper, Cape Ann Granite (1928; oil on canvas, 73.5 x 102.3 cm; Private collection) |

|

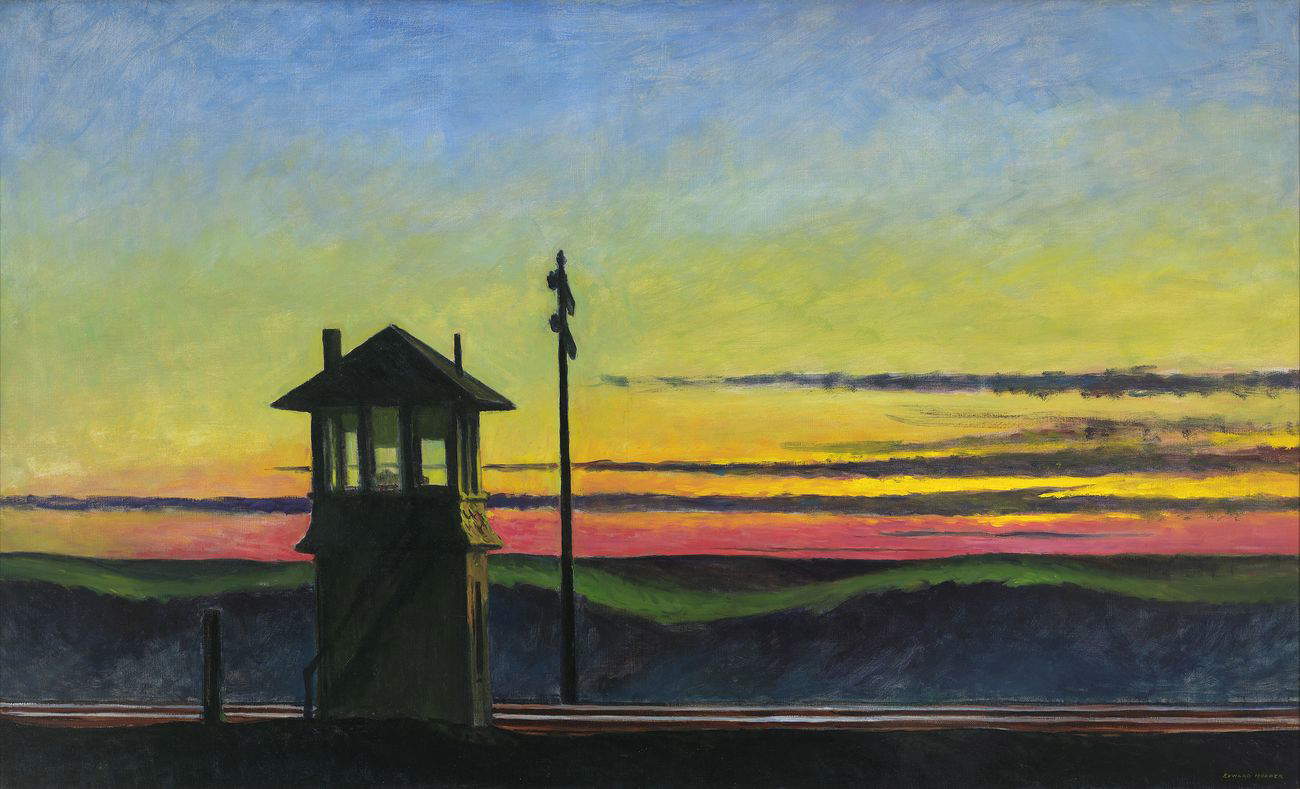

| Edward Hopper, Railroad sunset (1929; oil on canvas, 74.5 x 122, cm; New York, Whitney Museum of American Art) |

|

| Edward Hopper, Lee Shore (1941; oil on canvas, 71.8 x 109.2 cm; Middleton Collection) |

|

| Edward Hopper, Square rock, Ogunquit (1914; oil on canvas, 61.8 x 74.3 cm; New York, Whitney Museum of American Art) |

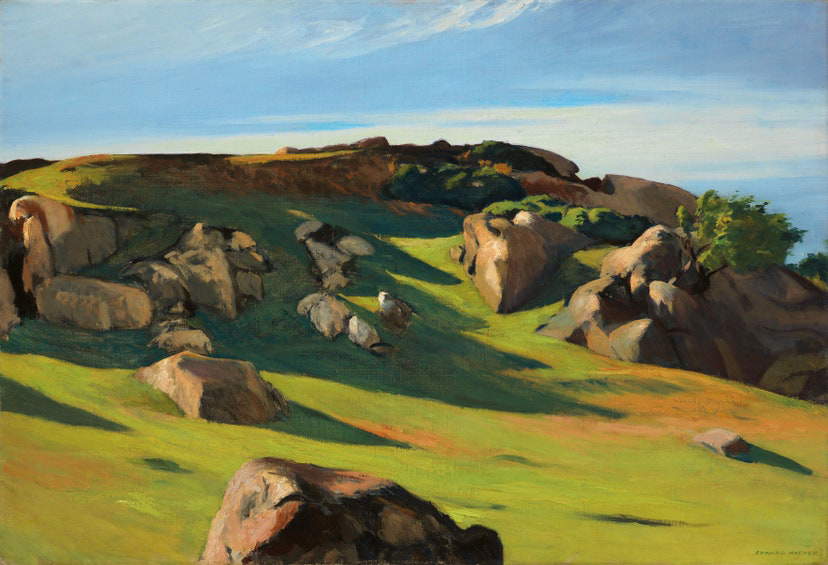

Human figures then totally disappear in Hopper’s typical landscapes describing vistas very close to the artist, such as the Whitney Museum of American Art ’s series of paintings set around Truro, Cornwall, the pastures with large granite rocks of Cape Ann, Massachusetts, the railroads encountered across America, and the hills on which a white lighthouse towers.

Hopper made the painting Cape Ann Granite, belonging to the Rockefeller collection and now part of the Fondation Beyeler as a permanent loan, in the summer of 1928, during which time he also executed numerous watercolors depicting the local landscape. Steep green pastures interrupted here and there by large granite boulders probably hang down toward the ocean, which lies to the right beyond the painting. The work shows a significant interest in the landscape and the light effects the painter is able to create on the meadows.

Railroad Sunset at the Whitney Museum of American Art, on the other hand, is built on an evocative use of color by following horizontal lines. Shifted to the left is the small railroad signal building flanked by a tall telephone pole, and over rolling green hills the sky turns red, orange, yellow, with splashes of blue, the colors of a spectacular sunset on the horizon. After their marriage, Hopper and Josephine Nivison undertook several train trips to Colorado and New Mexico, and in 1929, the year the artist painted this picture, they traveled from New York to Charleston, South Carolina, Massachusetts, and Maine. However, rather than a defined place, the painting is intended to show the vastness and emptiness of American landscapes, those that the couple certainly saw in the course of their travels.

Also less well known but no less significant are Hopper’s seascapes: thus, not only hills, pastures and roads, but also seas over which white dwellings stand, white sails unfurl and whose waves crash on rocks, as in Lee Shore of 1941 and Square Rock, Ogunquit, of 1914.

Edward Hopper’s landscapes deserve to be better known, on a par with scenes of urban life, as they give an idea of the true American spirit, often hidden by glitz and celebrities.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.