What happens when the memory of a place crumbles between the fingers, like ore dust extracted from the earth? Otobong Nkanga digs into the sediments of history, the fractures of the landscape, the invisible scars of matter. Her art is not content to be seen: it must be traversed, traversed with the eye and the body, like a map of layered meanings. Born in Nigeria in 1974, Nkanga has built an artistic practice that is both visual poetry and political geology. Her obsession is with matter: minerals, textiles, plants, water. All that is alive and all that has been exploited to the point of helplessness. His works are roots that sink into the soil of colonial extraction, cultural dispersion, shattered identity.

In Carved to Flow (2017), one of his most celebrated installations, soap becomes a metaphor for diaspora, journey, and transformation. Made from oils and minerals from different parts of the world, it is sculpted into dark, solid blocks, which over time wear out, dissolve, are distributed. Matter crumbles, adapts, migrates. Like memory. Like bodies in motion.

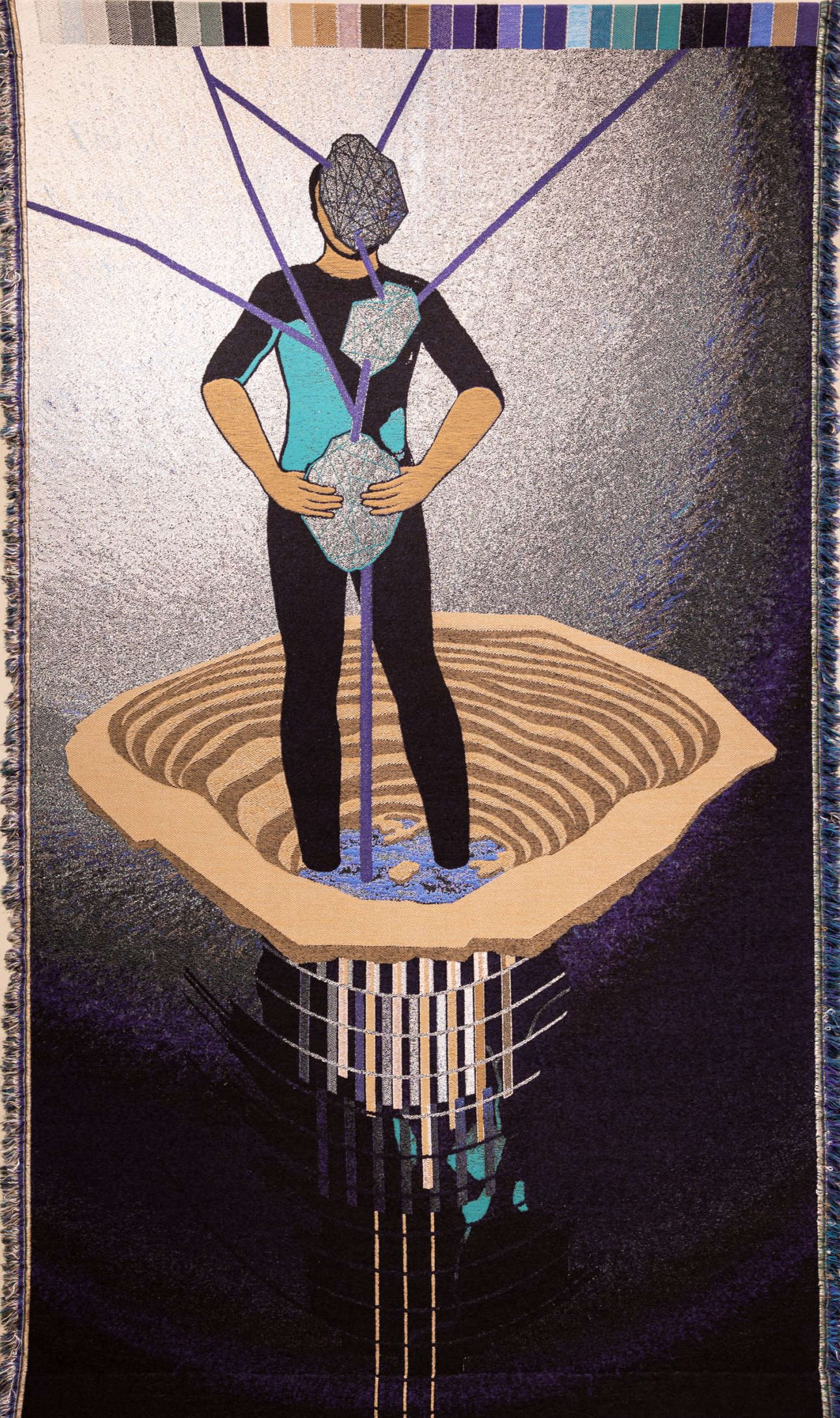

Nkanga often works with fabric: her tapestries, such as Infinite Y ield (2015), are not just weavings of threads, but maps of power, loss, and connection. In this work, a human figure merges with a mining structure, as if the skin itself were ore, as if the flesh were rock. Mining is not only about land, but also about body, culture, language.

But his investigation does not stop there. In Landversation (2014), Nkanga gives voice to the earth literally and figuratively. This performance and installation project is made up of encounters, dialogues and stories woven with local communities. It is an ever-evolving work in which people, with their words and experiences, become part of the artistic creation itself. The lands speak to each other, through those who inhabit them. The landscape is no longer a background, but a living subject, a witness and custodian of pasts intertwined with the present.

Theplant element, so often neglected in historical narratives, is another protagonist in his research. In Anamnesis (2015), Nkanga collects and reassembles fragments of plants and flowers that have traveled with humans, as silent spectators of migration and trade. Vegetation becomes a witness to colonial history, to the forced transit of people and cultures, to what is lost and what remains in the invisible traces left in the soil.

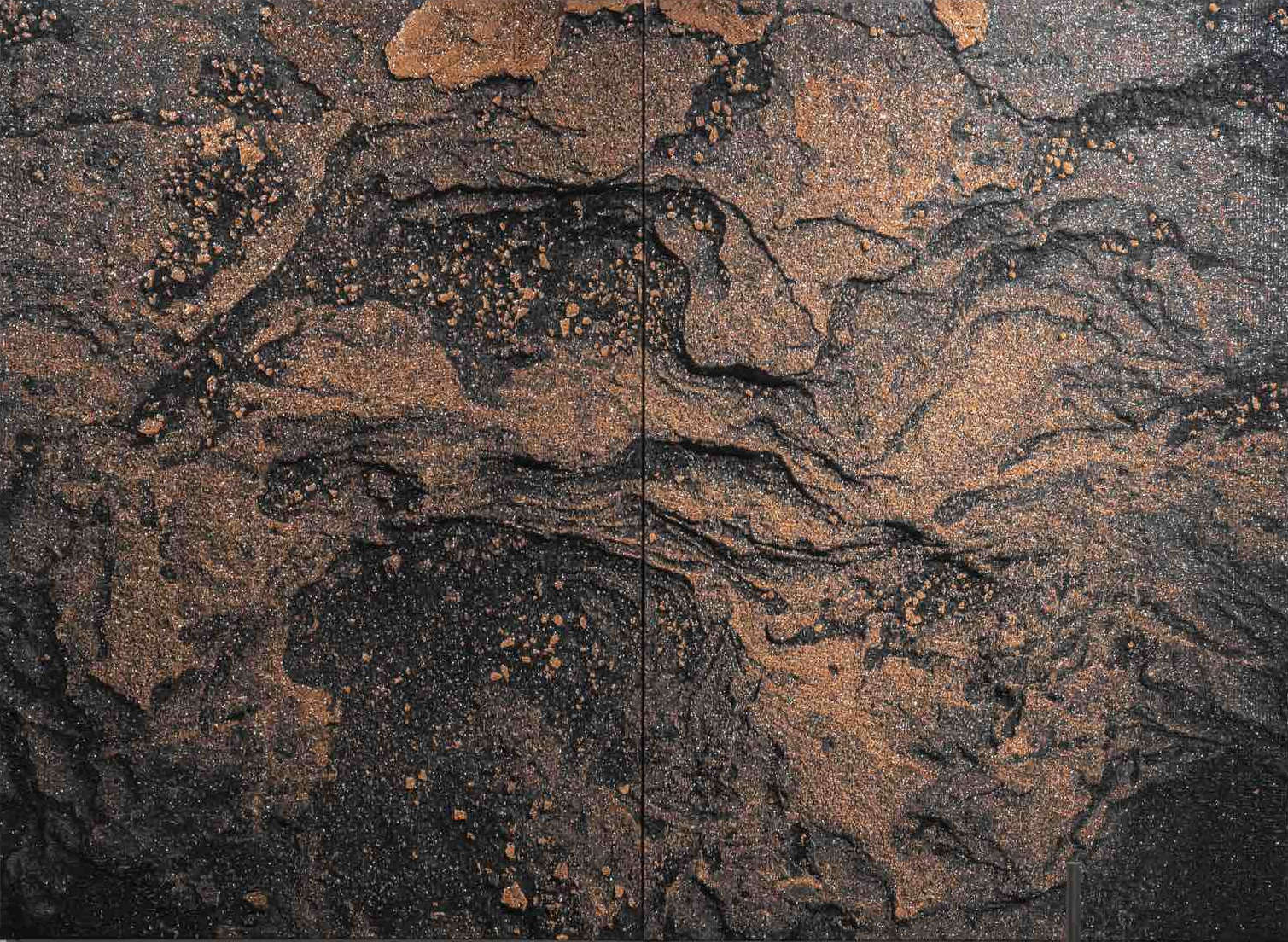

Another key work in his research is Steel to Rust (2016), in which the corrosion of metal becomes a metaphor for extractive economies and cycles of exploitation. Iron, a symbol ofindustrial modernity , rusts and dissolves, reminding us that nothing is eternal and that even the most solid structures are destined for transformation. Nkanga reflects on the paradox of a civilization that extracts resources from the earth to build, but ends up generating entropy and decay.

The materiality of his work collides and merges with time: metal that oxidizes, fabric that frays, soap that wears away. Everything is transformed, and in this metamorphosis lies the deepest meaning of his poetics. Change is not only an inevitability, but a revelation. His works are fragments of a conversation between the present and the past, between man and the matter that surrounds him.

Nothing is eternal, nothing is fixed. And in this metamorphosis lies the revelation: change is not an anomaly, but a law of matter and life. Nkanga listens to the sound of the earth, gathers its scattered voices, its whispers submerged in the soil. He challenges us to think of places not as mere spaces, but as bodies that absorb and return memories. His work is not only denunciation, it is also a hushed song, a dialogue with what goes before us and what will remain after us.

His works do not offer answers, but raise deep questions. What does it mean to belong? Where does our responsibility to the earth end? Are we custodians or predators of the soil that hosts us? After all, as Nkanga’s works suggest, everything is in motion. The earth, its wounds, its voices. And we, with it, continue to dig, to search, to question the weight of memory and the lightness of passage.

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.