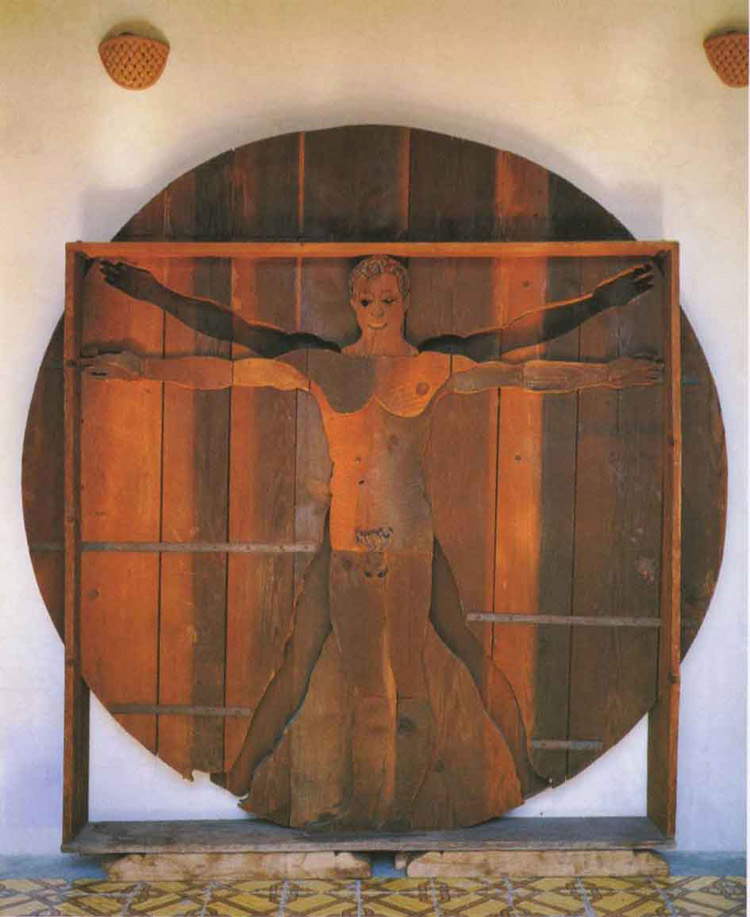

The story of one of the best-known and most photographed works of contemporary art in all of Tuscany, namely The Man of Vinci by Mario Ceroli (Castel Frentano, 1938), the monumental wooden sculpture that pays homage to Leonardo da Vinci’sVitruvian Man (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), begins far from Italy. It is 1967 and Mario Ceroli is in Graz, Austria, where he has been invited to exhibit at the Trigon ’67 exhibition, scheduled from September 5 to October 15 of that year at the Kunstlerhaus: it is a kind of biennial, founded in 1963, in which artists from three nations, namely Italy, Austria and Yugoslavia, participate. The theme of that third edition was theenvironment: artists were asked to propose works that could interact with the space in which they were immersed.

Ceroli, then 29 years old, was an artist who had already distinguished himself for theoriginality of his proposal. Coming from a family of modest economic conditions, he had already experimented with all possible materials, from marble to fabric, from paper to ceramics, but it was with wood that he found the dimension that was most congenial to him: wood is a poor material (and it should be noted that Ceroli was a forerunner of the trend that, from 1967 onward, would be defined by Germano Celant as “arte povera,” and with which Ceroli himself was also associated), and it is a material that allows the artist to work in complete autonomy on the work of art, without the need for a collaborator who must devote himself to preparations to allow the sculptor to shape his creation. He had begun his own experimentation with wood as early as 1960, fascinated by American pop art, to whose language some of the modes typical of Ceroli’s sculpture were linked, such as the seriality of elements repeated in an almost obsessive manner, or the habit of creating the compositions with cut-out silhouettes (in Ceroli’s case, cut out of raw wood). Often seriality itself becomes the theme of the composition: “Ceroli,” wrote Maurizio Calvesi, “proposes themes in which seriality results not as an illusory means of solicitation and multiplication of the image, but coincides with the theme itself, with the very idea to be represented.” In other words: when Ceroli decides to represent a row of people, the work “does not arise from the idea,” but rather “from the idea of representing the idea of the row: the visible pattern of the man in a row.” It is a kind of exploration of the possibilities of the image, and the possibilities that the image has of interacting with space.

The public and critics had already been able to appreciate these ideas in 1966, in an important solo exhibition at the Galleria La Tartaruga in Rome, where Ceroli had exhibited, among other works, The Last Supper made a year earlier, and now preserved at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome, which purchased it following the exhibition. The seriality, in this work, becomes even dramatic, since the repetition of the silhouettes, all identical, of the twelve apostles, makes the absence of Christ at the center stand out: the perfection of seriality is interrupted, almost as if men have been abandoned by divinity. Another masterpiece of those years is China, also from 1966, one of the first works in the history of art that went on to occupy an entire room, making the viewer directly involved: a theme that, moreover, would be explored in depth precisely during the 1967 Austrian exhibition. In this work, Calvesi wrote again, “one has instead, in some way, the celebration, which is also larvishly ideological, of a choral, positively collective humanity, nor could the sense of compactness be better visualized”: the scholar, moreover, noted how the famous terracotta warriors, to whose image the Abruzzese artist’s Chinese figures seem to refer, had not yet been discovered, and whose discovery would attest to “the almost miraculous truth of Ceroli’s intuition.” And if a work such as La casa di Dante of 1965 testified to Ceroli’s interest in living spaces, with its exploration of the possibilities of interaction between humans and the environments of a dwelling, his own personal reinterpretation ofancient art (incidentally also present in La casa di Dante, where one of the female silhouettes is a mulieval portrait by Pollaiolo) came to the fore with La Cassa Sistina, which had won the sculpture prize at the Venice Biennale in 1966. The imaginative idea that in the future entire monuments such as the Colosseum or the Sistine Chapel could be disassembled and shipped to every corner of the world (and, given the current system of exhibitions, we can say that Ceroli had another visionary insight at the time), had suggested to the artist the need to make a sort of Sistine Chapel packing case: at first empty, it was then populated with characters evoking those of the frescoes disassembled and arranged to be transported, and became an environment that could be walked through by viewers, again in accordance with Ceroli’s research on the interaction between viewer and space.

|

| Mario Ceroli, The Last Supper (1965; wood, 147 x 230 x 65 cm; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

|

| Mario Ceroli, China (1965; Russian pine, 200 x 500 x 1000 cm; property of the artist. Courtesy Mario Ceroli, Rome) |

|

| Mario Ceroli, Dante’s House (1965; Russian pine, 248 x 353 x 145 cm; property of the artist. Courtesy Mario Ceroli, Rome) |

|

| Mario Ceroli, Cassa Sistina (1966; Russian pine, 200 x 300 x 230 cm; owned by the artist. Courtesy Mario Ceroli, Rome) |

The relationship with the Renaissance has always been a constant source of inspiration for Mario Ceroli, who already in 1964 had worked on the theme of Leonardo’sVitruvian Man, with the work L’uomo di Leonardo (Leonardo’s Man): it was a sculpture that re-proposed, in wood, the scheme of theVitruvian Man, and which was part of a trend much practiced by Ceroli, who in those years had begun to create silhouettes of the characters of the great art of the past. Leonardo’s Man was not so much an interpretation of the work as a sort of translation into wood, which, however, already contained some motifs that would later be developed in subsequent works on the theme. Meanwhile, despite the impression of two-dimensionality, it was not a work conceived exclusively for frontal viewing, since the square was actually a figure endowed with its own thickness, the silhouette with spread arms and legs was carved out of wood, the figure was provided with a back, and Leonardo’s man had the features of Ceroli himself, who had thus wanted to self-represent himself as a Vitruvian man.

In 1967, for the Graz exhibition, Ceroli made a new version of L’uomo di Leonardo, which he would title Squilibrio. No longer a transposition of the drawing, but a true interpretation of the Vitruvian man in space: the square becomes a cube in the center of which Leonardo’s man is inserted (who now has arms and legs fixed on hinges, as if to suggest the idea of movement), and who in turn is inscribed in a sphere composed of wooden ribs. It is a monumental work: the sphere exceeds four meters in diameter, while Leonardo’s man alone is almost two meters tall. And it is a work that intends to develop Leonardo’s reflections, bringing his man to interact with an open space, with the world around him: “Ceroli,” wrote Arturo Carlo Quintavalle, “in the path from the first to the second version, accentuates the symbolic value of the character Leonardo, archetype of an organic and architectural (proportional) conception of the world.” The title of the work, then, was intended to cloak the second version of Leonardo’s man in a slightly ironic vein: if in 1964 Ceroli himself had become the Vitruvian man, in 1967 the title of the sculpture went in a diametrically opposite direction with respect to the intentions of balance that Leonardo had set out to achieve with his design. But it was an irony animated by a profound vision: the imbalance is not so much that of the work itself, but that of the reality with which man must daily reckon, and which is far removed from that harmony that governs the world of Vitruvian man.

|

| Mario Ceroli, The Man of Leonardo (1964; property of the artist. Courtesy Mario Ceroli, Rome) |

|

| Mario Ceroli, Squilibrio (1987; wood, height ca. 400 cm; Fiumicino, “Leonardo da Vinci” Airport). Ph. Credit Aeroporti di Roma |

|

| Mario Ceroli, The Man of Vinci (1987; wood, height 400 cm approx.; Vinci, Piazza del Castello). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Mario Ceroli, The Man of Vinci. Ph. Credit gonews.it. |

Squilibrio, after the exhibition in Graz, was a great success, so much so that the work would be exhibited on numerous other occasions. At the Badischer Kunstverein in Karlsruhe in 1969, at the Pilotta in Parma in the same year, and at the Palazzo Ducale in Pesaro in 1972, just to name a few of the early exhibitions. And several of his reproductions can be found in many Italian locations. One of them, made in 1987, is installed at Fiumicino airport. Another was donated in 1997 to the village of which Ceroli is a native, Castel Frentano, near Chieti. The one in Leonardo’s hometown is also from 1987, was donated by the artist to the municipality and, as mentioned in the opening, is known as The Man of Vinci. The work was placed in the center of the square that opens behind the Conti Guidi Castle, which now houses the Museo Leonardiano di Vinci, the first to have opened a permanent exhibition of Leonardo’s machine models.

In Vinci, perhaps Mario Ceroli’s Vitruvian Man has found its best possible location. On one side, the piazza opens onto the Tuscan hills surrounding the town, the landscape that recurs in so many of Leonardo’s works. Behind, the square, the castle, the ancient town. The Man of Vinci is thus arranged in a constant dialogue between man and nature. That dialogue so complex and difficult that Leonardo da Vinci investigated throughout his life.

Complete bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.