From June 11 to October 3, 2025, the Christian Stein Gallery in Milan is hosting for the third time a solo exhibition by Stefano Arienti (Asola, 1961), one of the most recognizable artists on the contemporary Italian scene. Serving as the setting for the exhibition Ut pictura poësis is the neoclassical salon of the gallery’s Milan headquarters: a space overlooking a secluded garden where tall, mature vegetation filters light and introduces a constant atmospheric vibration into the interior environment.

Arienti had already exhibited in this same place in 2019 and 2021, with two projects centered on the poetic transformation of personal, often banal photographic images, to which he restored an aesthetic status through hybrid techniques: crumpled papers, scratched surfaces, reliefs and abrasions. In those works, the relationship between visual culture and the natural world was articulated in a precarious but fertile balance that challenged traditional dualisms. The natural, the human, the urban, the technological: everything was on the same plane of a nonhierarchical vision, where the artistic gesture became an instrument for suspending conflict.

“By using techniques, one can achieve results that are always different ... I have tried over the years to show that you can make art, poetically, with a minimal gesture. That that gesture there, even a little obtuse and maybe repetitive, is crucial,” Arienti says. “The courtly space of Palazzo Cicogna, with its secret view of the garden, frames a sequence of four overlapping times: classical, renaissance, impressionist and contemporary. History, like geography, has always intrigued me.”

“His works always begin with something that already exists, but through different techniques it undergoes a reworking, transforming itself into something new and unprecedented,” writes Chiara Bertola, director of GAM in Turin. “He himself confirms in an interview that he would never ”produce anything new, because all creativity is already available: you just have to have the attention to go and discover it and make it become something personal.“ Arienti is more of a painter than a sculptor: he works with images and he himself considers himself a painter ”because I mainly make pictorial decisions, although I don’t paint in the strict sense.“ He does, however, work with the tactile values of painting, often intervening on painted or photographed figures by ’implementing’ or ’augmenting’ them with plasticine, with pongo, with puzzles. He adds matter to the image, to transform it and make it more tactile and more alive.”

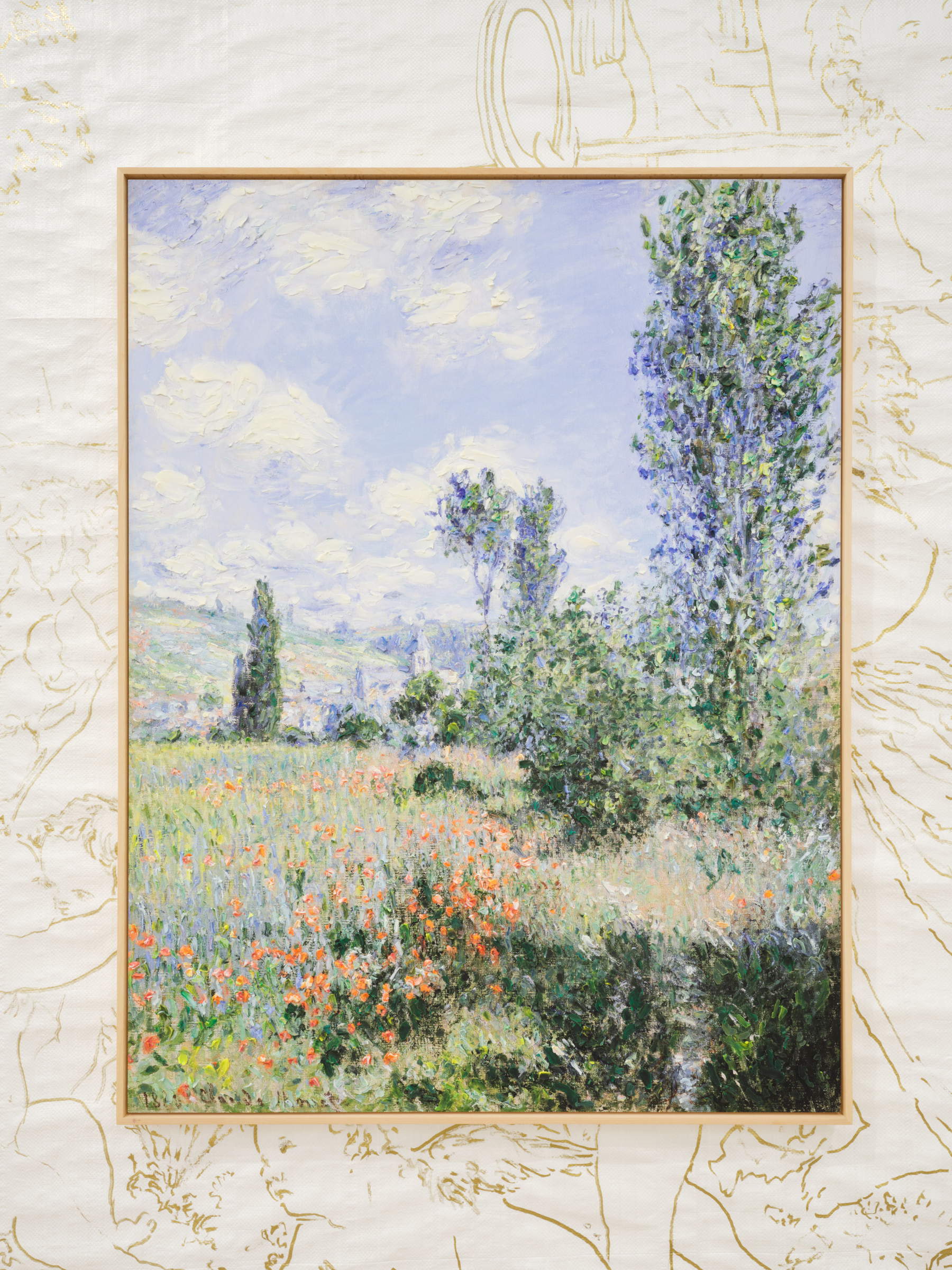

With Ut pictura poësis, a title that evokes the parallel between art and poetry, Arienti makes a return to his origins, but not in a regressive sense. Rather, it is a renewal of painting that passes through the memory, personal and collective, of founding gestures and images. The artist presents two series of works that, while formally distinct, recall each other in an interplay of echoes and correspondences. On the one hand, we find his famous compositions made with pongo, a poor and childlike material, but capable of a surprising tactile and chromatic density; on the other, the large, dust-proof, light, semi-transparent construction site tarpaulins, which accommodate barely perceptible, almost evanescent pictorial traces.

The pongo works represent a reflection on landscape and painting as a sensitive event. Arienti starts with well-known Impressionist paintings, particularly Monet, chosen for his insistence on capturing the elusive, and reconstructs them by manipulating the plastic material on the photographic surface. The original image dissolves but survives as an impression, as a visual echo. The color returns to being body and living matter.

“Everything is admirable, and every day the countryside is more beautiful, and I am bewitched by the country,” Monet wrote to his Parisian dealer Durand-Ruel.

The seemingly playful choice of pongo retrieves the free and original time of childhood, in which form and meaning arise from a primitive, unmediated intuition and restore a sense of discovery and enchantment to the creative act.

These works are flanked by large dustcloths stretched on the wall: diaphanous surfaces on which minimal signs emerge, light tracings that seem to evaporate in the air. Arienti calls them “more akin to large drawn tapestries, which spontaneously lay out in the architecture of the room,” and it is true: they are works that invite the viewer to slow down, to let the light pass through them. The artist has here evoked the technique of sinopia and spolvero, that phase of preparatory drawing that precedes the fresco, bringing out not so much a completed image as its possibility, its becoming. As if we are in front of a dream about to form, or a memory resurfacing.

Against these backdrops then stand out the pongo compositions, bright and full-bodied, harking back to the tradition of great Italian decorative painting. And here, in a further layering, Arienti cites Titian, taking up the famous mythological cycles painted for the Camerino d’Alabastro of Duke Alfonso d’Este: Bacchus and Ariadne, the Feast of the Gods, the Bacchanal of the Andrii, the Feast of the Cupids. Secular themes, taken from Ovid and Philostratus, in which intoxication, love and music become metaphors for beauty and transience. Arienti reworks, reinterprets, disassembles and recomposes.

The artist always acts on at least three levels: he manipulates materials and techniques with experimental curiosity; he collects, catalogues, and recycles images like an encyclopedic collector; and finally, and this is perhaps the most radical gesture, he renews the language of painting starting from its crisis. Not to close it, but to inhabit it poetically.

|

| In Milan, Stefano Arienti and painting as poetry: between Monet, Titian and the lightness of pongo |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.