One of the most renowned Italian painters who made macchia his stylistic hallmark was Giovanni Fattori (Livorno, 1825 - Florence, 1908). A painter and engraver(read more about Giovanni Fattori’s etchings here), he became one of the leading exponents of the Macchiaioli, a group of artists born at the Caffè Michelangelo, where its exponents gathered to talk about artistic and political themes: the name “macchiaioli” was first used in a derogatory tone by an anonymous journalist from the Gazzetta del Popolo who, in 1862, reviewed one of their exhibitions in hostile tones, scorning their theory of the “macchia” (i.e., the images of the macchiaioli are constructed through juxtaposed patches of color to give a sense of what the eye perceives in the immediate moment). The name that designated the group, in essence, came about in the same manner as the term "Impressionists": an initially disparaging term that later became the name by which the group identified itself.

Fattori was a painter much appreciated by his contemporaries mainly painted his beloved Tuscan landscapes, particularly those of the Maremma, but also for his portraits and works of peasants, workers and war episodes related to events contemporary to him such as the wars of independence . What made Fattori famous and much admired was his use of stain and color, always depicting realistic subjects.Very important for Fattori were his encounters with the painter Nino Costa, who supported him in his artistic research, but also his friendship with the art historian Diego Martelli , who guided the formation of the young Florentine group of Macchiaioli. In terms of the content of his works, Fattori rejected the celebratory themes typical of Neoclassicism as well as the nationalist ones: the painter preferred more realistic themes, and battles were not celebrated as other painters of the time did, but were more simply described, when not condemned through the depiction of tragic and discouraging episodes.

|

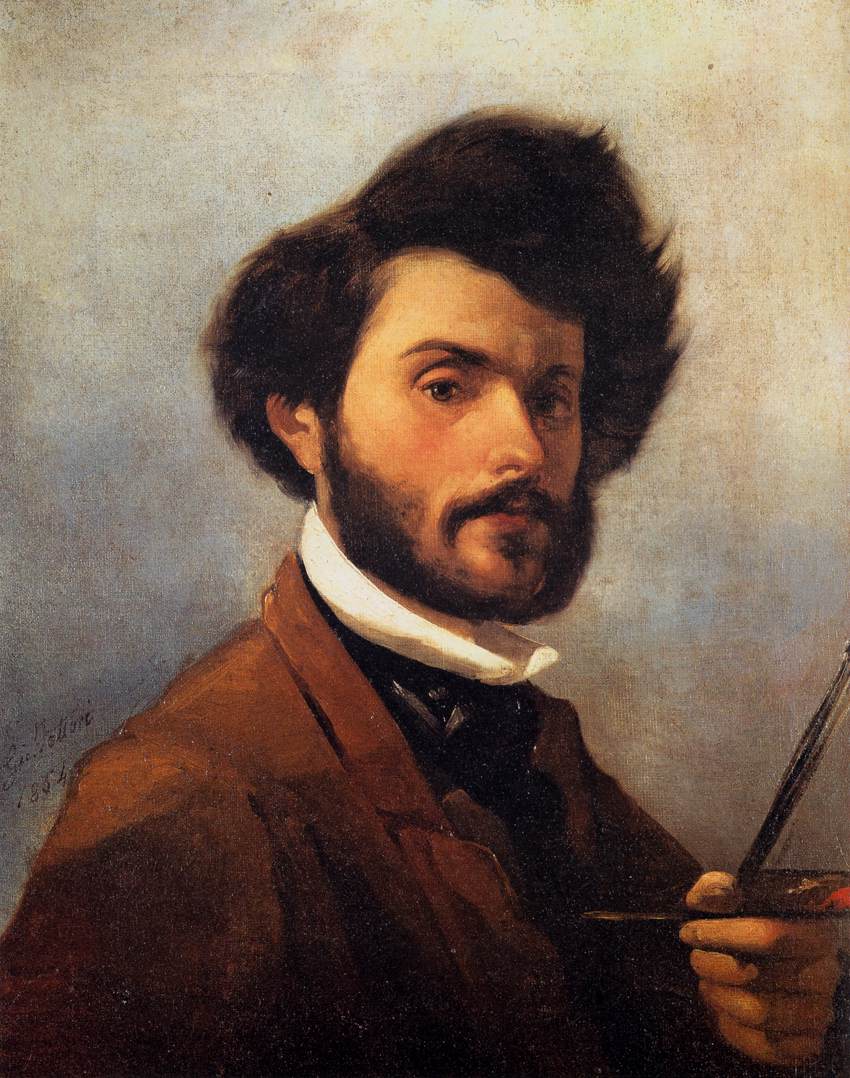

| Giovanni Fattori, Self-Portrait (1854; oil on canvas, 59 x 47 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Gallery of Modern Art) |

Giovanni Fattori was born in Leghorn on September 6, 1825, to Giuseppe, an artisan, and Lucia Nannetti, of Florentine descent. His older brother, Rinaldo, owned a business bank and initially made the young Giovanni work with him to start him in the trade: however, the boy’s artistic talent induced the family to start him toward artistic studies. Fattori’s first teacher was Giuseppe Baldini, but as early as 1845 the artist left Leghorn to move to Florence in order to enroll in the city’s Academy of Fine Arts , following the lessons of Giuseppe Bezzuoli. During these Florentine years Fattori bonded with a group of friends animated by democratic sentiments that greatly affected the artist’s moral formation. Among these friends were Costantino Mosti, the Nardi brothers, and Ferdinando Baldesi. Meanwhile, a revolutionary wind was blowing through the cities so much so that even Fattori, driven by youthful enthusiasm, devoted himself to spreading posters and “clandestine” press. The tragic events of 1848, which the painter experienced as a witness rather than a protagonist, marked the artist greatly. 1848 was also an important year because he opened the well-known Caffè Michelangelo in Florence, of which Fattori, from its opening, was a frequent visitor. From the very beginning, the Caffè Michelangelo gained a reputation as a meeting place for artists and patriots, and shortly thereafter the best-known Italian art movement of the 19th century, the Macchiaioli, the first group of independent artists driven by a strong sense of revolution, was born. These young painters asserted that form does not exist; if anything, it is created by light in the form of stain. Among the movement’s leading exponents, in addition to Fattori, were Telemaco Signorini, Silvestro Lega and Adriano Cecioni .

Having completed his academic studies, Fattori had to start earning a living, and thus began working as an illustrator for gazettes. Also attracted to landscape painting, he painted portraits of family members within landscapes. A tender friendship was born at the café with Settimia Vannucci, a woman to whom the artist later married in 1860 (the woman later died early of tuberculosis in 1867). Around the 1850s Fattori experimented with a new expressive technique, breaking away from the academic style. He portrayed from life French soldiers encamped in the Cascine, and these were his first experiments in spot-painting aimed at a particular realism that he derived from his meeting with the Roman painter Nino Costa . This was the phase of military subjects. The 1960s were devoted to pictorial experiments with macchia, which Fattori applied mainly to landscape painting and themes of daily work. In this period he greatly increased his executive freedom.

After the death of his wife in 1867, Fattori returned to Leghorn where he could concentrate on his works and fine-tune the new “macchia” technique, investigating the more concrete aspects of everyday life. His friend and art historian Diego Martelli contributed to this pictorial development. The friend hosted the painter at his estate in Castiglioncello, where Maremma landscapes became his favorite subjects. In 1875 the artist stayed for a few months in Paris, hosted by Italian painter Federico Zandomeneghi. The Impressionist artistic pursuits of the time did not fascinate the Leghorn painter much.

On his return from his Parisian sojourn he was hosted by the Gioli couple, noble intellectuals who were already friends of the painter and who hosted him in Fauglia, in the Pisan hills, where he painted expansive female figures within beautiful Tuscan landscapes. His notoriety is evidenced by his participation and victories at the Parma, London, Vienna, Dresden and Philadelphia Expositions during the 1870s. In 1869 Fattori received an appointment as professor in painting at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence, and in 1880 he was appointed honorary professor at the same academy. The military subjects and Risorgimento ideals that so exalted him when he was a young rebel in this period were diminished, so the subjects he painted changed: no longer soldiers and encampments (although the artist still produced paintings that denounced the conditions of combatants) but mainly canvases of bright, peaceful Maremma countryside occupied his studio. In 1880 the mature Fattori’s life was enlivened by a young woman, Amalia Nollemberger . The affair between the two lasted for a brief period, from the summer of 1880 to the spring of 1883, nevertheless the relationship was healthy for the painter who, in fact, infused his paintings with a more idyllic and gentle artistic vein. In 1882 Fattori was a guest of Prince Tommaso Corsini at his Marsiliana estate in Maremma. During this period Fattori discovered the butteri (i.e., shepherds on horseback in the Maremma) and made many engravings. In 1885 he met his widow Marianna Bigazzi, to whom he later married. At the end of the century Fattori produced many works, so many engravings are from this period, he also regularly participated in the Venice Biennale, since the first edition in 1895. On August 3, 1908, Giovanni Fattori died in Florence.

|

| Giovanni Fattori, French Soldiers of ’59 (1859; oil on panel, 15.5 x 32 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, The Italian Camp after the Battle of Magenta (1862; oil on canvas, 232 x 348 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria d’Arte Moderna) |

|

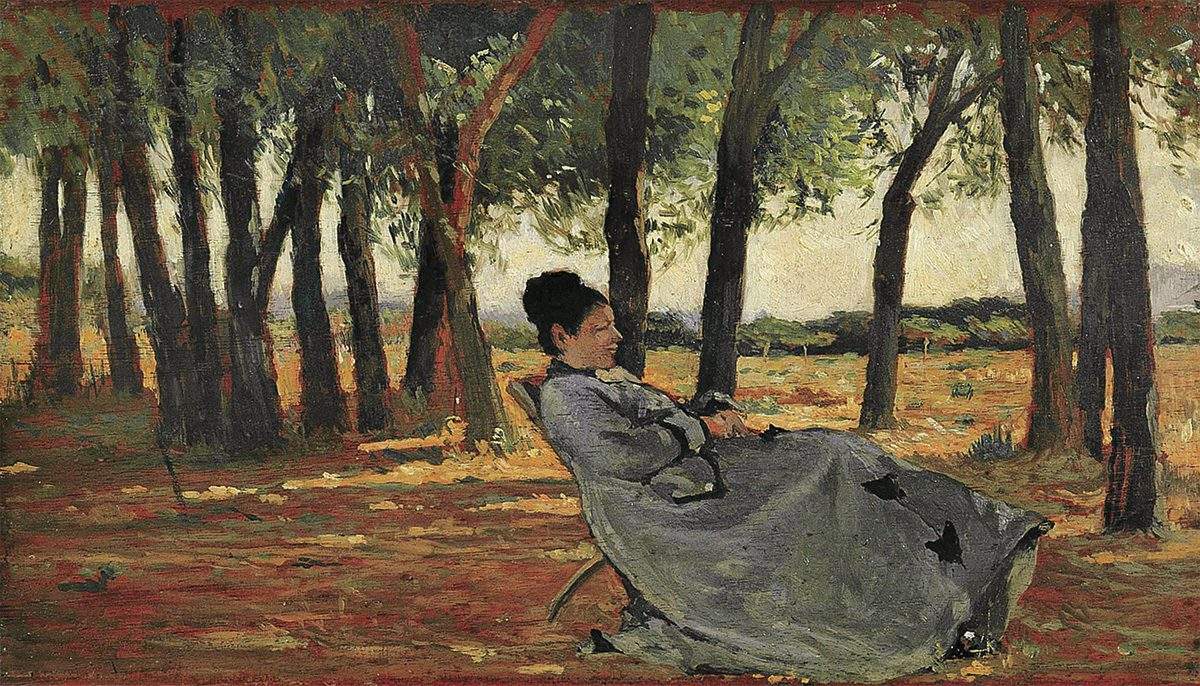

| Giovanni Fattori, Signora all’aperto (1866; oil on canvas, 10 x 22 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, La rotonda dei bagni Palmieri (1866; oil on panel, 12 x 35 cm; Florence, Galleria d’arte moderna di Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, Prince Amedeo of Savoy Wounded at the Battle of Custoza (1870; oil on canvas, 100 x 265 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

A journey through Fattori’s art can begin with French Soldiers (1859), one of the Leghorn artist’s first significant works. The young artist did not go into combat so he took the opportunity to paint passing French troops. The work documents the outbreak of the Second War of Independence, specifically when French soldiers landed in Livorno and then headed for Florence. In the work we see eight stationary French soldiers waiting for orders from the commander, who is on the right in the painting. The landscape was painted with a palette of very light colors that skillfully juxtaposed pervade the nine figures with a heavy air. Following theUnification of Italy in 1861, the new government wanted to celebrate the most significant moments of the Italian Risorgimento, so Fattori entered the competition by submitting sketches of The Italian Camp after the Battle of Magenta (1862). Having won the competition, the artist set to work: the interesting aspect of the painting is that the Leghorn painter instead of focusing on the famous victory tells us about the aftermath of the war. The subdivision of the canvas, in which the upper part depicts a clear and bright sky while in the lower part we see soldiers returning from the conflict, almost seems to give rise to a representation of heaven and hell. In the left foreground two corpses lie on the ground, while in the center a wagon carries nuns rescuing the wounded. Behind this tragic scene, the landscape is devastated by bombing; in fact, the colors tend toward gray. Stylistically, the work is still rooted in traditional painting technique, although “spots” begin to appear.

Signora all’aperto (1866) is one of Fattori’s most famous works; today it is kept at the Pinacoteca di Brera. The horizontal painting depicts a young woman on the rocks using a parasol to shield herself from the sun’s rays. The foreground is occupied by the rocks, while in the background a rich vegetation, descending to the sea, turns into a beach. The painting was one of Fattori’s most successful artistic experiments , and it was during this period that he improved the technique of macchia. In the canvas, in fact, the landscape and the figure are synthesized to the maximum. The work was created through geometric shapes and juxtaposition of spots of color. The style of the canvas is very similar to the famous Rotonda Palmieri (1866), a work in which in a limited space the artist tells us about a carefree moment of the Tuscan bourgeoisie. Seven women, some talking others looking at the landscape, are under a pontoon tent or rather, a rotunda as the work’s title suggests. Fattori used a wooden support that was not prepared for the application of color; in fact, one can see airs from which the material can be glimpsed. As in the previous work(Signora all’aperto), here too the painted subjects were made by superimposing broad backgrounds of color bordered by soft geometric shapes. There are no particular marks either in the women’s faces and bodies or in the landscape around them. The main color is ochre, visible in the lower and upper parts of the marquee, while the figures stand out for their darker colors tending toward grayish.

In 1870 the artist returned to the theme of war and once again, as he did nine years earlier in the work The Battle of Magenta he left no room for warlikecelebration but crystallized the drama of war in the canvas. The work in question is Prince Amedeo di Savoia Wounded at the Battle of Custoza in which soldiers help the prince, confused among other figures, to reach the ambulance that rescues him. The ambulance cart is located in the left part of the painting, flanked by bare trees. Bringing the eye to the far left we notice corpses lying on the ground. On the opposite side is a group of soldiers on horseback, and behind them stands a bright landscape, in stark contrast to the content of the painting. Compared to previous works, the stain is not used here in its most abstract form, yet the figures are hinted at with quick brushstrokes, without too much attention to the rendering of details. The use of stain is most visible in the composition of the grass.

An undated work is La Signora Martelli a Castiglioncello (c. 1867), however, it can be assumed that the work was created during the stay in Castiglioncello(read more about the relationship between Giovanni Fattori and the sea here) by his friend Diego Martelli, where the painter went after the death of his wife Settimia Vannucci. The painting depicts a woman in a gray dress resting her a deckchair enjoying the Tuscan landscape. Behind her a group of trees allows a glimpse of a pine forest on the horizon. The Macchiaioli technique is very noticeable here: in fact, the portrait of the lady standing in the shadows is done through the juxtaposition of colors. Warm colors are used to paint the Maremma terrain characterized by colors such as ochre, yellow and red, while the vegetation is constructed through the juxtaposition of green and gray tones.

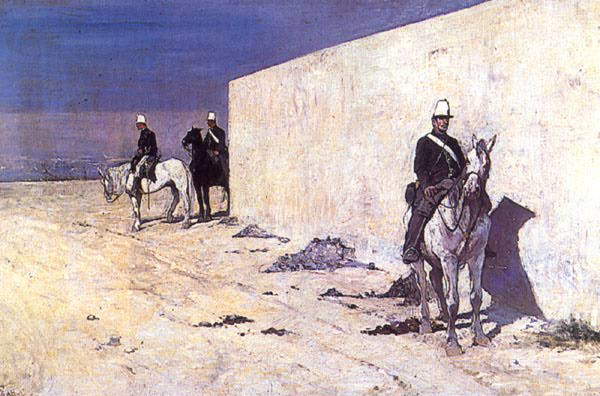

In vedetta (1872) is one of Fattori’s most famous works; it is a visual expression of time standing still. The canvas depicts few elements, three soldiers on horseback and a white wall stretching along the ground. Simplicity is taken to the highest level. The wall on the right reflects the sunlight, and in the foreground a soldier on a white horse in a dark uniform casts his shadow on the wall. Carrying the gaze deeper, two more soldiers, also on horseback, appear at the end of the long white wall. The figures are set in an empty, barren environment that exudes a sense of deep loneliness. Here Fattori demonstrated his extraordinary ability to render a strong visual impact with a few simple elements.

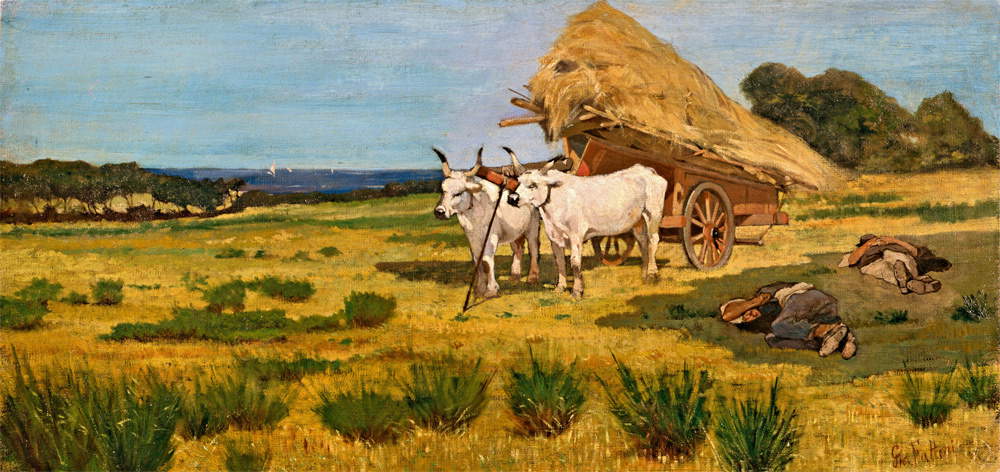

Rest in Maremma (1875) was made during his stay with the Gioli couple, a period in which his favorite subjects were the endless Tuscan countryside and the people working in it. In this work, the painter depicted the moment of the afternoon rest of two peasants flanked by a wagon full of hay pulled by two white oxen that stand out against the surrounding landscape, composed of colors tending toward ochre and yellow, while on the horizon stands out the white blue of the sea. A similar work in terms of subject choice is The Rest (Red Chariot) (1897), in which the two white oxen occupy most of the canvas, on the left the farmer rests in the shade, while on the far right the chariot is depicted. Wide fields of color make up the painting’s subjects, which are positioned along the diagonal given by the shadow. Of quite different significance is The Stirruped (1880), a work depicting a dramatic scene of a man falling from a horse. Many scholars believe that the episode represents the disappointment of many young men who fought for the Risorgimento ideals, to which Fattori himself entrusted all his hopes. What we see is a bolted horse running on a dirt road, and a fallen soldier has his foot stuck in the stirrup. The brushstrokes, with their elongated shape, also help to better express the tragic nature of the painting, just as the color palette, predominantly dark green, gray, and ochre also contributes to this dramatic effect. Giovanni Fattori’s works predominantly depicted peasants, soldiers, and Tuscan landscapes, which depicted in their simplicity through essential splashes of color he knew how to deal with themes that were not easy to elaborate in an original way.

|

| Giovanni Fattori, La Signora Martelli at Castiglioncello (ca. 1867; oil on panel, 20 x 35 cm; Livorno, Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, In vedetta (1872; oil on panel, 37 x 56 cm; Valdagno, Marzotto Collection) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, Resting in Maremma (c. 1875; oil on canvas, 35 x 72.5 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, Rest (red wagon) (1887; oil on canvas, 88 x 170 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

| Giovanni Fattori, Lo Staffato (c. 1880; oil on canvas, 90 x 130 cm; Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Galleria d’Arte Moderna) |

In 1994 Livorno, Giovanni Fattori’s hometown, decided to name its civic art gallery after the painter. The “Giovanni Fattori” Civic Museum is housed in the atmospheric Villa Mimbelli, and this is home to a large collection of Fattori’s works, including Portrait of his Third Wife (1905), Lungomare di Antignano (1894) and La Signora Martelli in Castiglioncello.

In Florence, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna, located in the imposing Renaissance Palazzo Pitti, boasts a conspicuous collection of Giovanni Fattori’s works, both those of a historical nature and landscapes, such as The Italian Camp after the Battle of Magenta (1862), The Stirruped (1880) and The Palmieri Rotunda (1866). In Milan, the Pinacoteca di Brera houses Il Riposo (1887) and Il principe Amedeo di Savoia ferito alla battaglia di Custoza (1870). Some of Giovanni Fattori’s etchings are instead in the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art.

|

| Giovanni Fattori: life, works, the Macchiaioli painters |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.